On the day they bombed Colorado, Rifle mayor Lesley Estes was a guest at the reviewing station, standing under a large circus tent. He knew that important people such as Dr. Edward Teller, father of the hydrogen bomb, were among the crowd gathered at a remote site in the state's mesa country on September 10, 1969. But he spent most of his time chatting with his friends from town. Like him, they had gathered to witness the biggest thing ever to hit Rifle: the detonation of an underground nuclear device more than twice as powerful as the bomb that exploded over Hiroshima in 1945.

Set off as part of Project Plowshare, a government effort to use nuclear weapons for peacetime purposes, the Rulison bomb was intended to shake loose millions of cubic feet of natural gas for the benefit of two private energy companies. Mayor Estes didn't object to the idea of unleashing the nuclear genie a mile and a half inside the earth. In fact, he won the trucking contract on the job.

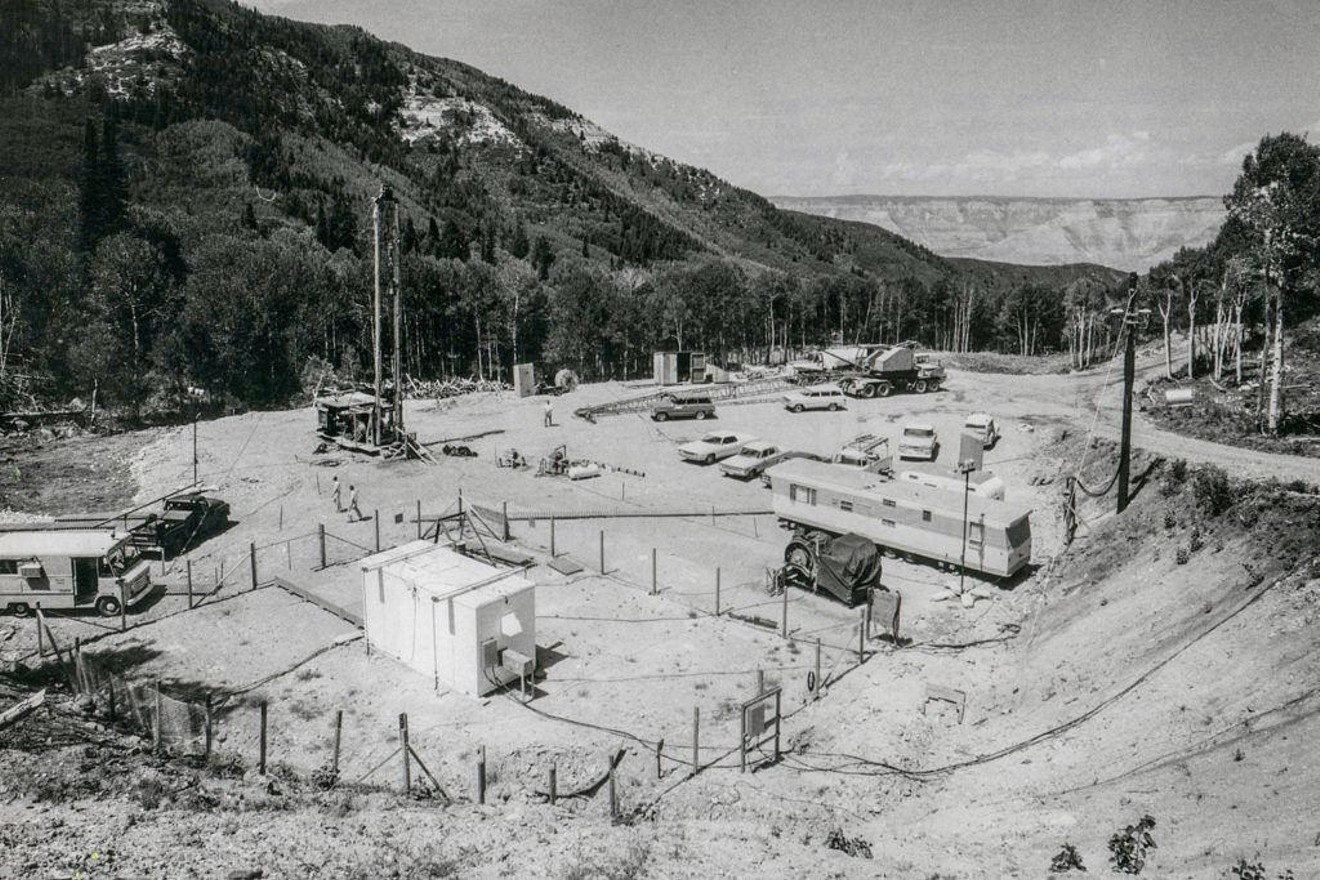

"I had a trucking business at the time, and that was a good contract, hauling in all of the rigs and whatnot," Estes remembers. Those rigs were being used by government crews to drill a hole 8,430 feet deep and just fifteen inches wide near the ghost town of Rulison, halfway between Glenwood Springs and Grand Junction.

Estes's company didn't get to haul the long, thin bomb up from the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in New Mexico. "They had fellows from the government that were in charge of the bomb the whole time," he says. "I had a pass, though, to go up there any time to see how things were coming along."

Things were coming along just fine, but Estes didn't pay much attention to that. He just made sure the trucks ran on time.

Years later, one of the energy companies that paid for the blast, Austral Oil Company of Houston, invited Estes down to Texas for a dinner honoring those who had worked on the project, which never produced the hoped-for gas bonanza. "They had made some cuff links out of the rock that was right at the blast site, and they gave me the first pair," he says. "I still have them around here someplace." The mayor never tried them on, though. "I don't have the kind of shirt where you use cuff links," he says. "All my shirts have buttons."

Like Lesley Estes's cuff links, the Rulison blast was an awkward fit for Colorado. It sparked an early environmental battle that Dick Lamm lost, but one that he says helped launch the state's environmental movement, along with his own candidacy for governor. Scientists such as Teller still believe the idea was a good one that was hamstrung by people with an irrational fear of nuclear weapons. Local residents generally had the same reaction that Estes did: They hoped to make a buck off the bomb but remained instinctually wary of a proposal that, if successful, could have led to a string of as many as 1,500 nuclear explosions across Colorado.

Today, memories of the blast have resurfaced as part of a new political battle brewing on the Western Slope. Energy companies have returned to the area around the Rulison site and once again are poking holes in the earth in search of natural gas. Some residents fear the new round of exploration is increasing the odds that radioactivity trapped for years in the subterranean rock may be brought to the surface.

Just as it did with the Rulison project three decades ago, the government says the latest effort is perfectly safe. But many residents—along with a Republican lawmaker who represents them at the state legislature—question those claims. And nearly thirty years after the Rulison bomb went off, its aftershocks are still being felt.

For Edward Teller, the road to the Western Slope began in Germany, where the Budapest-born researcher was studying at the University of Leipzig alongside Werner Heisenberg, then known as the world's leading molecular scientist. When Hitler came to power, other physicists told Teller that as a Jew, he would have no future in Germany. He took their advice and moved to America.

Teller's old teacher, Heisenberg, had developed the first theories of how atoms work. And even as American scientists came closer to designing an atom bomb, Teller knew the Germans could be even closer. The odds were good that a bomb of previously unimagined strength could soon be in Hitler's hands.

Teller, though, resisted joining the war effort until the Nazis invaded his native Hungary. After that, he needed no more convincing: He joined the group of physicists working on the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico. His work there earned him a reputation as the "Father of the Hydrogen Bomb," a title he still bears proudly.

After the war, Teller remained an advocate for the use of nuclear bombs, and his steadfast devotion created a rift among his fellow scientists. By the early 1960s, he proposed Project Plowshare, a reference to the biblical injunction to "beat their swords into plowshares."

Now ninety and living near San Francisco, Teller says he still believes the Plowshare projects he proposed were a good idea. They included plans to use above-ground explosions in Alaska to make a new harbor for oil supertankers and blowing up a large portion of Nicaragua to carve out a new canal.

Rulison was far less flashy than that but, says Teller, held great economic promise. By exploding a nuclear bomb underground, he and others hoped that natural gas trapped in small pockets in the bedrock would be set free and would rise gracefully to the surface, where it could be piped off at a great profit.

Teller watched the explosion at Rulison, but he has seen dozens of such blasts and says that that day in 1969 doesn't stick out. "My memory of the last couple of decades is not that good compared to my memory of the early part of my life," he says.

But Teller remembers that Rulison was important. If it had worked, it would have been the first of a series of projected nuclear explosions in Colorado to "stimulate" gas production. And he's still chagrined that that never happened. "It is a great pity," Teller says, "that these peaceful uses of nuclear power have never been able to become fully mature."

When government officials decided to try the Rulison experiment, they picked a "surface ground zero" site on a mesa south of the Colorado River, not far from Battlement Creek. Although there are millions of acres of federal land in the area, Atomic Energy Commission officials picked a spot that was part of 292 acres owned by Claude Hayward, a 73-year-old potato farmer trying to scratch out a living on ground that scarcely supports the native sage. "This land has damn little anything except for clean, clear water," says Claude's son Lee, now 79.

Still, when emissaries from the AEC came to the elder Hayward and told him they wanted access to his land and would pay him $100 a month for the rest of his life, he initially said no. "I was afraid it would foul up the water, the one good thing we got, so I told him not to sign it," remembers Lee. "But my father was a gullible man."

Claude's grandson, Craig Hayward, was eighteen at the time. Now an accountant living in Boulder, he still has the contract his grandfather signed. People living around Rulison at the time "knew the square root of zip about radioactivity," Craig says. But "these fellas from the AEC came back around with a whiskey bottle and got him good and juiced up and said they would pay him $200 a month for the rest of his life. Well, even though my father had told him not to sign it, he did."

John Green, Kate Donithorne and Chester McQueary knew a little bit about radioactivity—enough, at least, to make them suspicious of plans to ignite a nuclear bomb in their backyard. So they became protesters, though not exactly the "long-haired hippie radicals" described at the time by the local papers.

The 32-year-old Donithorne was a conservatively coiffed mother of two small children. Green was 30, with three kids and a crewcut. Of the three, only the 35-year-old McQueary, a devoted member of the American Friends Service Committee, came close to fitting the newspapers' description.

There were few environmentalists in those days, but McQueary's interest in monitoring the government's nuclear program went back years. He had grown up in the town of Granby, and in his senior year of high school, in 1953, had taken a class trip to Nevada and Utah. One day when the class was on its way to St. George, Utah, McQueary says he witnessed a memorable incident: "These very polite men in white suits came on the bus and told us that if we wanted to drive to St. George, we could, but that we had to keep the windows up the entire time, and if we didn't want to agree to this, that we couldn't go. Then they insisted that it was perfectly safe and there was no danger to any humans."

It wasn't until years later that McQueary learned he and his classmates had stumbled across one of the most troubled nuclear experiments ever. It had the code name of "Harry" and later became known as "Dirty Harry" because of an unexpected wind shift that rained radioactive fallout on the town of St. George. So when McQueary learned of plans for another nuclear experiment sixteen years later, he and his fellow protesters decided to take action.

"Because of their 'deep concern' for human beings, they announced that they would not do any nuclear explosions if there were any people within five miles of the blast site," recalls McQueary. "We decided to hold them to their deal."

McQueary, Green, Donithorne, fellow protester Margaret Puhls and about a dozen other people figured they would sneak into the area near ground zero and set off smoke grenades so that officials would know there were people inside the five-mile buffer zone.

The group had to make a couple of trips to the site, as the blast was delayed several days because of weather. Officials said they wanted to wait for a day when the wind wouldn't carry any radioactive fallout over populated areas. The AEC also promised not to blast on a weekend, when tourists might be delayed by necessary road closures.

"There was a restaurant in Rifle that put 'Thou shall not blast on Sunday' on their sign," says Donithorne. "We got a kick out of that."

After a week of delays, the blast was set to go forward on Monday, September 10. The protesters broke into pairs and fanned out across the site. "We decided to separate so they couldn't pick us all up in one fell swoop," McQueary says. Each pair carried a portable radio and listened to the countdown, which was being broadcast by a Grand Junction radio station.

A few minutes before the blast, the protesters set off their smoke bombs. Moments later, two Air Force helicopters appeared, one for McQueary and Puhls and another for Green and Donithorne, who were at least two miles away.

The chopper that came for McQueary and Puhls wasn't able to land on the steep hillside, but an armed man opened the door and started yelling something to them. "Of course we couldn't hear a word he was saying," McQueary says. He figured out that the federal agent was motioning for him to move to a place where the chopper could land, but McQueary would have none of it. "After all of this, I was not about to just march into their arms," he says. "We had come too far for it to end like that. We were scared, but we weren't going to willingly turn ourselves over."

Green and Donithorne weren't as lucky. A helicopter landed within a few dozen feet of them, and they were forced aboard at gunpoint. Donithorne remembers being exhilarated. "I understand how much fun war games can be," she says. "I can see what makes war so appealing. Aside from getting killed here and there, it's very exciting."

The helicopter carrying Green and Donithorne lifted off, then hovered over the area until the blast.

McQueary and Puhls remained on the ground. "We figured out later that we were the closest to ground zero," he says. The two had consulted several scientists on how to prepare for the blast. As the countdown approached zero, they took the experts' advice: Having cleared all the large rocks away from a patch of ground, they lay on their bellies and waited for the shock wave to hit them.

McQueary says his memories of the seconds before the blast are crystal clear: "I remember looking into [Puhls's] eyes and there was a real sense of fear there, and I'm sure she saw the same."

Tom Lamm was in Washington, D.C., when the bomb exploded, but he, too, was jolted by the blast. Along with his brother Dick, Lamm was fighting the Rulison project in the courts as an attorney for environmental groups. He'd been given the assignment of carrying the appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Tom Lamm, who today practices law in the Denver area, says it was a great thrill going to Washington. But he admits the only reason he got to appear before the nation's highest court was that he'd lost everywhere else. "We got our butts kicked every step of the way," he recalls.

By the time the Supreme Court agreed to listen to Lamm, the Rulison bomb was already in the ground, and the fissionable matter inside was decaying. A delay of two weeks more would have made it unusable. And because it had been buried under thousands of feet of gravel and concrete, it could never be retrieved.

The court was out of session, and the justice who normally would have presided at the emergency hearing, former University of Colorado football star Byron "Whizzer" White, was on a fishing trip. The case was assigned to Justice Thurgood Marshall. "I was terrified, of course, because I didn't know my ass from third base," Lamm says. If the notion of appearing before the high court wasn't bad enough, there was the press to worry about. A group of reporters were lying in wait when he arrived for his last-minute injunction hearing on September 10.

"There must have been a hundred people out front with cameras and mikes and everything," Lamm recalls. "So I asked the cab driver what was going on, and he said that some lawyer is flying out from Colorado to try to stop the nuclear explosion. Well, I had to tell the cab driver, 'I'm that guy,' and I think even the cab driver knew that I was in serious trouble. He was a grizzled old guy, and he knew I was wet behind the ears. I asked him if knew some back entrance to get into the building, and luckily, he did."

Inside, the situation wasn't much better. "I got kicked all over the court, but everyone was real nice because they all knew that I was just a dumb kid from Colorado," Lamm says. He lost the hearing, an outcome he fully expected.

"I wasn't in any hurry to talk to [the press], so I took my time, and I stopped by as I was leaving and thanked all of the clerks for being so nice," he remembers. "The press people didn't mean to intimidate me, but they did. I got outside and they were all waiting, and the first thing they said was that the bomb just went off and did I have any reaction? All I said is, 'It didn't take them long, did it?'"

Practically the entire populations of Rifle and Grand Valley (later renamed Parachute) turned out for the blast. They'd been told that while there was no real danger, they should probably leave their homes when the time came. Most went to their respective Main Streets and stood around waiting for the detonation.

Mary Satterfield took her two toddlers down to First Street in Grand Valley. She wanted to share the moment with relatives and found much of the rest of the town gathered along the main drag. "Everybody was excited about it," Satterfield says. "It was the big event."

The front lawn of Grand Valley's only school served as another gathering place. "Whenever we had a gathering of any size, we would go down to the school," remembers Bobbi Wambolt, who grew up in the town. She says the wait for the atomic blast was reminiscent of cookouts, carnivals and fairs held on the school lawn.

"Everybody took a picnic and made a fun afternoon out of it," says Wambolt. "At the time, people weren't nervous because they didn't know anything about it, really." She remembers being irritated by the protesters who'd come in from out of town but says that most of her fellow citizens paid them little mind: "Most of the people in town were farmers and ranchers, and they don't tend to get too upset about anything."

Wambolt also remembers an out-of-town reporter standing on the school lawn, trying to find out if a child was crying because he was afraid of the impending blast. "That child wasn't crying out of fear," Wambolt says. "That child was crying because his mother had just hammered him."

The Atomic Energy Commission set up a large tent to host the muckety-mucks from Austral and CER Geonuclear of Las Vegas, the company set up to conduct the actual field operations. Also sampling the doughnuts were a collection of state and local officials, along with some of the residents who lived inside the buffer zone.

Colorado governor John Love was scheduled to be at the tent the day of the blast. The plan was that Love, state natural resources director Tom Ten Eyck and newly appointed state geologist John Rold would fly to the area in a state plane scheduled to leave Stapleton Airport before sunrise.

When Rold, who'd started work only a few months earlier, got to the plane that morning, he found no Love and no Ten Eyck, just a note. "The note said that I was the one that would be going on behalf of the state and that I would have to give a speech," he recalls. Because of the weather delays, the blast was now set for the same day that Love was hosting a national governors' conference in Colorado Springs.

The bomb was going off, though, governor or no governor. "I considered this a pretty momentous occasion, so I wrote a speech in the plane on the way over that to my mind reflected that," Rold says. His speech focused on the risks that Colorado pioneers had faced through history. In his mind, the Rulison project would have made Colorado's early settlers proud.

Environmentalists had hoped that Love would call a halt to the blast, much like commuting a death sentence at the last minute. Rold did speak to Love on the phone before the blast; he recalls the conversation clearly. "He just asked me one question: 'John, is it going to be safe?'" Rold says. "I had studied it quite hard for a few months, and in my opinion it was, and I said so. I didn't go on and on, because I figured what he needed was just the bottom line."

The governor gave his okay, and Rold gave his speech—or at least most of it.

"I was about three-quarters of the way through the speech when these long-hair extremists came in and sat right up on the platform," Rold says. Many were carrying signs that read "No Contamination Without Representation." "I suppose they were trying to intimidate me, and I suppose they did," says Rold. "My main reaction was that I wanted to give them a knuckle sandwich."

Rold restrained himself, though, and arranged a compromise with the protesters: If he could finish his speech, he'd turn the microphone over to one of them.

That deal sounded good to protester Bruce Polich, a World War II veteran who owned a restaurant in Aspen at the time. He says he thought the idea of the blast was crazy, in part because he believed it might threaten a dam upstream from his hometown. "As the crow flies, Rulison wasn't far from Aspen, which was still a town that was worth saving in those days," he says.

So Polich and a group of other locals invaded the tent just as Rold was nearing the end of his speech. Rold and Polich both remember what happened when Rold finished and Polich stood up to speak: Most of the oil-company executives and local contractors got up and migrated toward the coffee and doughnuts.

"I talked for a little while, and I think some of them paid attention," Polich remembers. "I remember saying that I thought [radioactive] gas was nothing to fool around with, and certainly not something I'd want piped into my home."

The only place where Polich's memory disagrees with Rold's is in the state geologist's description of the protesters. "That was no crazy hippie movement," Polich says. "There were no psychedelic buses—we were responsible people."

As the time for detonation drew near, the protesters and politicians all turned into the same thing: spectators.

Unlike the "Fat Man" and "Little Boy" devices that exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Rulison bomb never had a nickname. The queerly shaped instrument of destruction measured fifteen feet long but was only nine inches in diameter, manufactured in the approximate shape of a pencil so it could be inserted into the long, skinny blasting hole. Filled with uranium-235, it weighed 1,200 pounds and was encased in a refrigerated, pressurized canister.

Much of the information about the blast is still classified, and the federal Department of Energy, successor to the Atomic Energy Commission, won't say exactly who gave the command to detonate the bomb.

Less reluctant to discuss the project is Hal Aronson, who was president of CER Geonuclear (which no longer exists). "We put in almost all of the money," says Aronson. "But someone from Los Alamos had the final say-so.

"There wasn't really a button to push, anyway," he adds. "It was more like an electronic timing device."

Just before the blast, Lesley Estes says he remembers overhearing a government agent being told that a couple of protesters—Green and Donithorne—had been picked up by a helicopter. "After that, he said, 'I don't see any more of them; start the countdown,'" Estes recalls.

Once it began, the countdown was carried live over KREX radio. Gene Rozelle was the entire news department, covering everything from high-school wrestling to cattle futures. Now retired, he remembers the Rulison countdown as a "dramatic event."

When the electronic timer reached zero, a pulse was sent to the explosives that surrounded the rods of uranium. Forced together, the U-235 molecules turned supercritical and exploded.

The bomb did a little better than the expected 40 kilotons. Scientists later determined that the blast yield was 44 kilotons, or the equivalent of 44,000 tons of TNT. By comparison, the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, had a yield of 15 kilotons.

The bomb had been placed in a layer of solid rock. Once detonated, it vaporized the rock all around it, carving out an empty cavity 350 feet high and 76 feet across. It fractured rock for hundreds more feet in all directions, freeing natural gas as expected. (As predicted by opponents, the gas was also rendered radioactive, and millions of cubic feet had to be burned off at the site because it was too dangerous to sell.)

The closest structure to ground zero was a 100-year-old log cabin owned by the Haywards. "It survived, all right, but the whole thing moved about six inches," Craig Hayward says.

The shock wave spread in all directions, including through the air, where the helicopter that had picked up Green and Donithorne was hovering over ground zero.

"Even though we were about 2,500 feet in the air, we could feel that shock wave hit us," Green says. "It bounced us up and down pretty good." Donithorne remembers thinking that she was handling the situation well, but Green told her later that it had taken a couple of days to get the feeling back in his hand because she'd been squeezing it so hard.

The first people on the ground to feel the shock wave were McQueary and Puhls, who were about two miles from ground zero. McQueary was ready for it, because he'd been listening to the countdown on the radio.

The blast hit him at almost the exact moment he heard zero on the radio. "There's no way to describe the strength of the shock wave," says McQueary, who remembers being bounced six or eight inches into the air. "The best analogy I can give is laying down next to some train tracks and having a huge freight train go right past you at unbelievable speed. There was just such a sense of power and noise right near you."

C.W. Byerrum, now a social studies teacher at Parachute High School, saw the shock wave coming from his spot near the official viewing area, where he was hanging out with some friends. Although he was nineteen years old at the time and trying to act cool, he says he remembers his astonishment at seeing the ground move in ways he'd never seen before.

"You could see this wave coming along the ground toward you," Byerrum recalls. "We didn't know it was going to be that severe."

Mayor Estes was braced for the blast, but its strength surprised him, too: "It was like you were getting hit on the bottom of your feet with a sledgehammer."

The people in Grand Valley stayed calm, says Bobbi Wambolt, whose husband worked as a contractor at the blast site. Nearly every brick chimney in town fell down at once, but Wambolt says that wasn't the scariest part. The most frightening thing was the rumbling from the enormous cliffs that hover over town, an ominous noise that continued for 30 or 45 seconds. It was the sound of hundreds of rocks falling.

The tumbling rocks sent up huge plumes of dust, and John Rold at first feared that the blast may have "vented" clouds of radioactive gas to the surface. "But soon we could see that it was just dust," he says.

Marilyn Latham remembers officials telling her family members that they probably wouldn't be able to feel the blast in the town of Rifle, which was farther from ground zero than Grand Valley. "They told my mother that if she wanted to watch it, she should put a pan of water out in the front yard and watch it for ripples when they blew up the bomb," Latham recalls. "Well, she sat there watching that pan, and the shock wave came and splashed water all over her and then put a huge crack in the foundation of the house."

At first, the impact of the Rulison blast seemed to have subsided along with the shock wave. Green and Donithorne were taken to the Garfield County Jail in Glenwood Springs on a charge that they had set off fireworks (the smoke grenades) in a national forest. But after officials figured out that the two had been plucked off private land, they figured the only thing they could charge them with was trespassing. To press that case, authorities contacted the property owner. "He didn't want to press charges, because his chicken house fell down and he was mad about that," says Donithorne.

The local papers on the Western Slope never did print their names, referring to them only as the "long-haired protesters."

Atomic Energy Commission officials compensated those who had lost chimneys or suffered other damage to their homes. Even people who are still angry at the government agree that those payments were made quickly and without much fuss. "They handled that about three-quarters right," Lee Hayward says, though he's still peeved that the government failed to clean up a holding pond used as a dumping ground by drilling crews.

Hayward also says his father never got the $200 a month promised him. Under the contract Claude Hayward had signed, he got paid only if the well made money for the energy companies. "We never got a dime out of it," Hayward says.

In the long run, neither did Austral or CER Geonuclear, which saw most of their potential profits disappear when they had to burn off the gas that was too radioactive to sell. Some gas was eventually produced for commercial use, but by then Claude Hayward wasn't around to share in the proceeds. He had died of cancer two years after the blast.

It was only after a few years had passed that the lasting effects of the Rulison blast began to be recognized. The explosion helped reshape Colorado's political landscape, says the man who rode the shock wave into the governor's office in 1974.

Dick Lamm says the fact that Rulison never fulfilled the doomsday prophecies of critics—among other things, it was feared that the bomb might irradiate the Colorado River—doesn't change his mind about the project's foolishness. He knew the odds of a disaster were small, but he says that's beside the point. "The point I was making is that what's important is not the odds, but the stakes," Lamm says. "Even small odds are unacceptable if the stakes are too high, and this was a case of blowing up a nuclear bomb in a way that could contaminate the entire Colorado River basin with tritium. It was insanity."

Lamm says he appreciates the genius of people like Teller and the other scientists. "He's obviously got a huge IQ, but he is monomaniacally focused on nuclear energy," says Lamm. "And this wasn't even nuclear energy, this was nuclear bombs."

The group of people who came together to oppose Rulison stuck together afterward. "That battle led the way to the Olympic battle," Lamm says, referring to the successful effort he spearheaded to prevent Colorado from bidding on the 1976 Winter Olympics.

However, the group wasn't able to prevent yet another Project Plowshare blast in Colorado. That one, also funded by Austral and CER and known as Rio Blanco, was even larger than Rulison. On May 17, 1973, three 30-kiloton bombs were exploded in one long hole in a remote section of Rio Blanco County in northwestern Colorado. Again the idea was to release natural gas trapped in subterranean rock; again the effort failed to make money for its investors. It came and went without much fanfare, sparking fewer protests than Rulison and getting lost amid coverage of Watergate and other stories of the day.

Lamm went on to support a citizens' initiative, passed by a wide margin in 1974, that amended the Colorado Constitution by adding a unique clause. If any group wants to blow up a nuclear bomb in Colorado, the measure now must first pass a statewide vote of the people. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Colorado is the only state in the nation with such a provision.

CER Geonuclear's Hal Aronson, who is now retired and living in Palm Springs, California, says the constitutional amendment was a stake through the heart of Project Plowshare. "There was a bunch of crackpots who didn't really understand it, so they were against it," Aronson says. He characterizes the Rulison protesters as "kids driving their BMWs and their Saabs, spending all of their fathers' money, but they hadn't taken a bath for several weeks. They were just a cause looking for a place to happen."

However, the protesters' point of view took hold even in the U.S. Congress, which killed all federal funding for Project Plowshare in 1975.

Rulison remained a forgotten footnote in Colorado history for more than a quarter-century. It came bubbling back to the surface this past September 19, when a column of natural gas blew out a private water well at Wendell Goad's home near Rifle. A plume of water and natural gas shot twenty feet into the air for most of the day before crews could control it.

The blowout at the Goad place quickly got the attention of people in Rifle and the retirement community of Battlement Mesa. That's because the gas had come to the surface about 4,000 feet away from the well where it was being mined. Nearly everyone in the area lives within a mile of a natural gas well—or will, now that the state has given energy companies the green light to drill hundreds of new wellheads. For residents who'd already been protesting the new state guidelines, the Goad geyser was the last straw. "They say it won't happen again, but they also said that it wouldn't happen in the first place," says K.C. Binger, who moved to the area three years ago with her husband and two small children.

Over the past four years, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (OGCC) has granted requests by energy companies to increase the legal density of wells in the Rulison and Grand Valley gas fields, from one every 640 acres to one every 20 acres. With the increased drilling have come increased concerns about gas contamination of water wells—and about radioactivity, since crews are poking holes in the same area as the nuclear blast.

In response to those fears, the Department of Energy has run several tests of wells near ground zero. Those tests have found no evidence of radioactivity. However, many residents remain dubious of the DOE's claims; one of them is Russ George, the Republican state representative from Rifle. George was a student at Harvard Law School at the time of the Rulison blast. He says he distinctly remembers going down to the student union to watch it on television. "The people who did the explosion in the first place are now the same people telling us that it's safe," says George. "I have no confidence in them."

George has been negotiating with landowners and the OGCC to force gas companies to better address the concerns of "surface owners" like Binger, who are legally obligated to let energy companies onto their land to pursue mineral-rights claims. As a result of those negotiations, a series of public hearings were held last week in Greeley, Rifle and Durango.

OGCC director Rich Griebling says claims that his agency hasn't taken public complaints seriously are untrue; he points to last week's hearings as evidence that the commission is interested in hearing both sides of the issue. Gas companies working in the area are doing a good job, Griebling insists: "They are going beyond the requirements in reclaiming the environment and doing other things for the good of the surface owners."

Frank Keller, executive vice president of Barrett Resources Corporation, the company doing most of the drilling in the area, says his company has tried "awfully hard" to meet the needs of surface owners. He says most people in the area support the economic development that comes with drilling, but "there are a vocal few who seem to raise a lot of issues. You just can't please everybody."

A prominent burr in the industry's saddle is Meeker attorney Frank Cooley, one of the longest-serving mineral-rights lawyers in Colorado. Meeker studied geology before opening his legal practice in the early 1950s. In 1969 he battled the AEC over the Rulison blast. Now he's working against what he says is an industry-controlled OGCC.

"At least with the Rulison project, we had our say," Cooley says, noting that the battle went to the Supreme Court. "That case couldn't approach the level of contempt and arrogance shown on the issue of well-spacing by the OGCC."

Charles Worley remembers taking time away from his Cedaredge plumbing business in 1969 to protest the Rulison explosion. "We would go down to the Methodist church to use the mimeograph to make copies of our fliers," he says. Those limp leaflets, printed with fading purple ink, contained scientific information about potential negative consequences of the bomb not covered in the local press. There was even some poetry. "We waged quite a propaganda campaign to try to get people to stop and think," Worley says.

In 1980, Worley helped found the Western Colorado Congress, a group that now uses electronic mail, faxes and other high-tech means to fight the expansion of gas drilling. "They're way past that old mimeograph machine," says Worley. Now eighty, Worley says he sees similarities between his battle against the bomb and the current fight against drilling rigs. "It's the same fight," says Worley. "There are just different weapons."

Today Worley's memories of the Rulison blast remain crystal clear. "It shook us all up pretty good," he says. "It shook the cars around us. It sent these huge rocks cascading down the face of the cliffs." Like many other observers, he mentions the wave that came toward him on the ground.

Craig Hayward remembers seeing that wave, too. "The ripple just moved along the ground like a wave in the water," he says. "It shook the bejeezus out of the whole countryside."

Hayward watched the blast from a distance with his father, Lee, and grandfather Claude, the man beneath whose potato patch the bomb blew up. Claude may already have been regretting letting the government explode an A-bomb on his property for a bottle of whiskey and the promise of a few hundred dollars. But, says Lee Hayward, the old man was still impressed with what he saw.

"I remember my dad saying, 'Goddamn, that was a good one,'" Lee says. "And his face was just white as a sheet."