Craddock’s enchanting world is the setting for a novel, An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors, that he began working on a decade ago; it was just published in August. Breathtaking in scope and packed with the aspirations and machinations of a rich cast of characters, Alchemy is the kind of fantasy that seems tailor-made for the genre’s swelling fan base — a fan base fueled in recent years by the runaway success of HBO’s Game of Thrones. Craddock’s publisher, Tor Books, even counts Game of Thrones’ George R. R. Martin among its authors; Martin’s popular anthology series Wild Cards is published by Tor, which claims the title of “the most successful science fiction and fantasy publisher in the world.” Tor is also the home to many other sci-fi and fantasy luminaries, including Orson Scott Card, Robert Jordan and Philip K. Dick.

“It feels good to be making a contribution to the fantasy genre,” Craddock says. Tall, soft-spoken and sporting a graying goatee that’s a bit swashbuckler-ish itself, he sits in a room at Tacticon, one of Denver’s annual gaming conventions. Around him are gamers heading to their next session of Dungeons & Dragons or Pathfinder. Down the hall, a man in a pointy wizard’s hat gives chair massages. Local companies selling gaming paraphernalia such as miniatures and colored dice line the concourse. “There’s a lot of despair in the world right now,” Craddock continues. “The timing is unfortunately good, and people want something to cheer them up a little bit. I want to light a candle against that. I want to give people heroes that they can cheer for.”

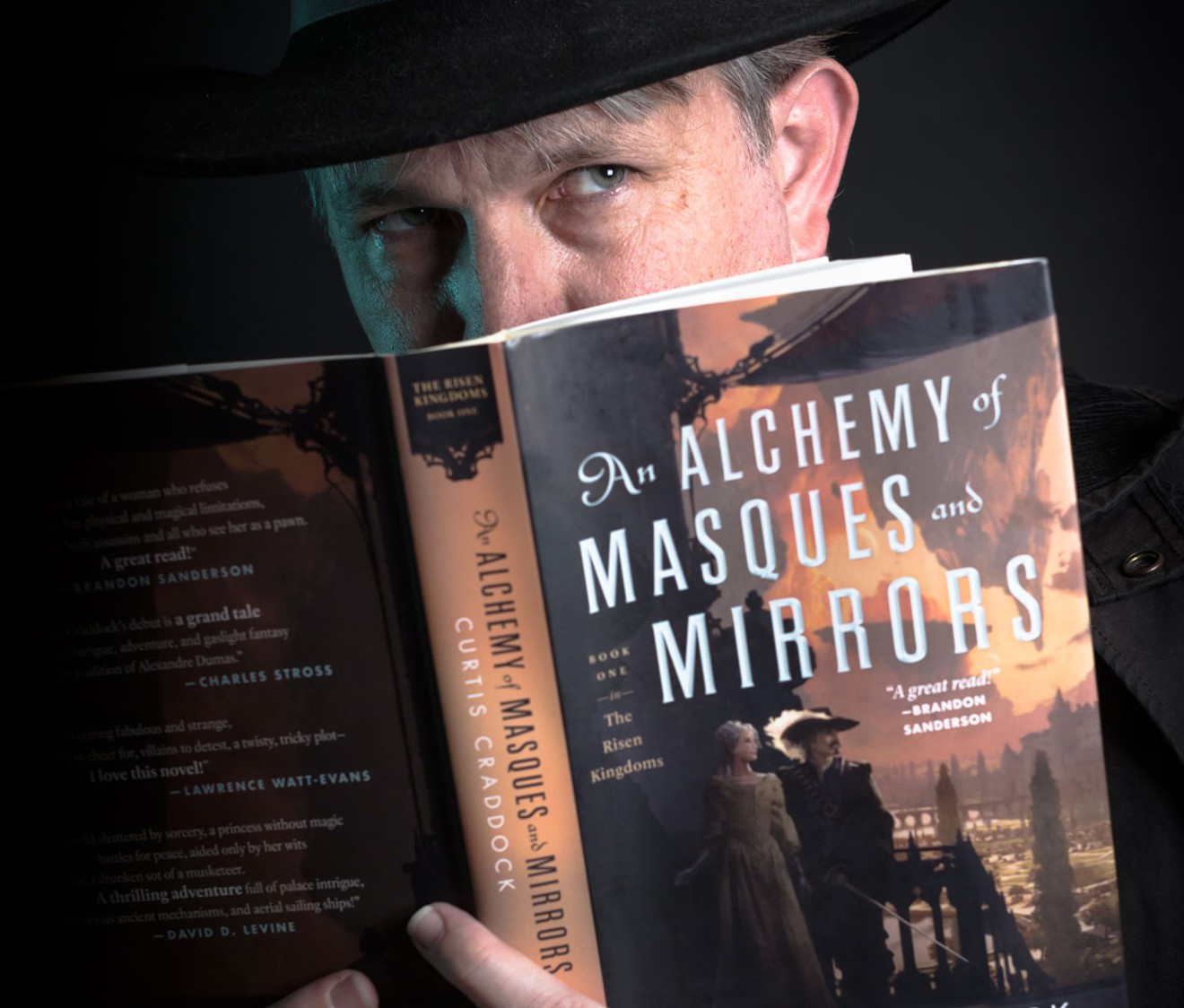

Alchemy is the first installment of a trilogy called The Risen Kingdoms, and Craddock is already finishing the second book, which will be titled A Labyrinth of Scions and Sorcery. If Alchemy’s reception so far is any indication, the trilogy has a strong chance of becoming a hit. Renowned sci-fi and fantasy authors such as Brandon Sanderson and Charles Stross have sung Craddock’s praises. The Washington Post applauded Alchemy for being “a classic fantasy”; it also received starred reviews from Booklist and Kirkus, the latter calling it “a very promising start, both for a series and a new author.” The book’s cover art certainly doesn’t hurt its appeal: Lush and majestic, it was painted by Thom Tenery, a concept artist for the last two Star Wars films.

Despite Kirkus’s generous words, Craddock isn’t exactly a new author. He’s been at it for more than three decades, since he was a high school kid in Las Cruces, New Mexico, who couldn’t seem to excel at much besides making up fanciful tales about strange worlds. His path to authorship was strewn with setbacks, heartbreaks and depression. Alchemy isn’t even his first published novel, though his literary debut seventeen years ago was anything but a triumph. And even as Alchemy seems poised to capitalize on fantasy’s newfound popularity, Craddock takes issue with the genre as it stands today — and he includes the work of Martin among the problems.

“Curtis Craddock was born in the wrong century and quite possibly on the wrong planet,” the author writes of himself on his website. “He should have been born in a world where gallant heroes regularly vanquish dire and despicable foes, where friendship, romance, wit, and courage are the foundations of culture and civilization, and where adventure beckons from every shadow.” Instead, he was born in Texas. As Craddock quips with his dry, deprecating sense of humor, “I was born in Houston General Hospital in 1968, right across from the zoo, and my mother told me that she got me mixed up with an ape.” His mom was an occupational therapist; his dad was a physicist for NASA who published academic papers that revolved around the spectrographic readings of supernovas.

“His specialty wound up being high-altitude weather balloons and balloon experiments,” Craddock explains. “He spent some time down in Antarctica doing that. He had this experiment down there where he was trying to capture a column of air. It was, like, thirty miles high. The instrument he was using was only capable of collecting an accurate sample if it was falling straight down. If you know anything about the weather in Antarctica, it’s very windy. So he had developed and built a parachute that would fall straight down in a high wind.” Craddock and his father also constructed and launched model rockets together. It’s no wonder that Alchemy dwells on the intricate aerodynamics of the beautiful airships that fly between continents, one of the many ways in which the book is far more complex than the average sword-and-sorcery story.

When Craddock was ten, his family resettled in Las Cruces after his dad was offered a position at New Mexico State University’s Physical Science Laboratory, one of the leading aerospace developers in the country. The transition was jarring. “I didn’t know anything about the place. I thought roadrunners were purple,” Craddock says with a laugh, referring to the famous Looney Tunes cartoon character. “It was weird. I didn’t know anybody. I had always done my own thing, and I was not good at making friends. I couldn’t pronounce ‘Mesilla’ properly. The first few years in Las Cruces were not so good. I like Las Cruces as a town much more as an adult than I did as a child.”

Craddock, however, made friends of a different kind: those he found in the pages of science-fiction and fantasy novels. His parents were constant readers, and they raised their son to be one, too. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, which he precociously devoured at the age of ten, initiated him into speculative fiction. From there he dove into legendary authors like Robert A. Heinlein, Andre Norton and Fritz Leiber. “I was a nerd,” he says. “I read books all the time. I spent most of my time buried in books. I was drawn to science fiction because my house was full of it. Nothing was too advanced for me, according to my parents. If I didn’t understand it, I didn’t understand it. So what? You get more out of it that way. Basically our house was a library with beds in it.” Alchemy is dedicated “To Mom and Dad, who encouraged me to read whatever I wanted.”

“I liked the imagery associated with science fiction and fantasy,” Craddock says. “I liked knights, and I liked spaceships. Knights were basically superheroes. They got to dress cool. Later on, I learned that most knights were complete bastards, but that didn’t deter me. People shouldn’t get the sanitized version of history.”“There’s a lot of despair in the world right now…. I want to give people heroes that they can cheer for.”

tweet this

As much as he loved reading, it didn’t reflect in his grades. Craddock would even cut class — not to go out and raise teenage hell, but to go to the school library and study what he wanted, at the pace he wanted. “I was a terrible student. I always had to figure things out myself, because no one else’s explanation ever made sense to me. I actually got chastised once for reading in class. I wasn’t paying attention to my teacher because I was reading a book, and I had to write 500 times on the blackboard, ‘I will not read in class.’”

He thought he might become a physicist like his father, but by his own admission, Craddock “didn’t have the math for it.” Instead, he drifted into writing. “In the twelfth grade, I had a creative-writing teacher,” he says. “Her name was Mrs. Wright, surprisingly enough. She told the class to turn in a short story, just to gauge them, and I wrote a fantasy story. After she read it, she told me I had an A in the class. All I had to was keep writing short stories and submit them to contests. So I started doing that.” He was so inexperienced, though, that he began submitting stories without even giving them titles. He failed to win anything or get his work published, but it didn’t matter. “I never stopped writing from that point,” Craddock remembers. At seventeen, he’d found his calling.

Something else fed into his love of writing: role-playing games. Craddock had begun playing Dungeons & Dragons while in junior high in the early ’80s. The game, first published in 1974, allowed players to imagine themselves as characters in an elaborate, largely self-created fantasy story stocked with magic and monsters. A decade later, it had become a cultural phenomenon, prompting a backlash from God-fearing adults concerned that the game was a form of satanic worship. “I ran into one kid in junior high who had a copy of The Dungeon Master’s Guide,” Craddock says, referring to one of Dungeons & Dragons’ core rulebooks. “We would come up with the weirdest things. I don’t think anyone in Las Cruces knew what we were doing. But it was exactly the stereotypical nerd stuff that you would think it was.” He branched out into video games as well as the Society for Creative Anachronism, an organization of gamers who dress up in makeshift armor, fabricate fake weapons like swords and battle axes, and enact military battles in real life.

“I also played soccer in high school,” Craddock adds. “I was on the team, and my dad was the coach, but I didn’t make any friends through soccer.”

Gaming helped prime his ability to create the twists and turns of a plot, not to mention the gritty particulars of fantasy characters and settings. Nonetheless, his short stories failed to sell to a publisher. After high school, Craddock enrolled at New Mexico State, graduating with a degree in English in 1990. His girlfriend at the time, who had studied biology, wanted to move to Colorado; they relocated to Aurora and married that same year. His wife was soon hired by the State of Colorado as a wildlife manager, and the couple moved again, this time to the tiny town of Two Buttes in the far southeast corner of the state. “If you don’t know where that is, neither does anybody else. Its population is fifty, depending on who’s coming to visit,” Craddock jokes. While his wife pursued her outdoor vocation, he pursued his indoor one: He spent every day at the keyboard, crafting weird new worlds in which to escape. She supported them both, and Craddock threw himself into becoming a professional fantasy author.

“My writing career hit so many lumps and bumps,” he says. “I got involved with one of those companies where you have to pay someone up front to be your agent. And I lost most of the money I had that way. And I was never any good at getting short stories published. I’ve only ever had one published. I overwrite, and my short stories always want to blow up into novels.” After switching his focus to novels, he went on to write numerous drafts of books — eight in total, many banged out on a manual typewriter — none of which gained traction with agents or publishers. With little else to do in Two Buttes, he kept at it, but he sank deeper into a pit of rejection. For a time he considered becoming a game developer, going so far as to earn an online degree in video-game design from the Art Institute of Colorado. But nothing came of that.“The notion of the depressed artist is ridiculous. Depressed people do not do art. Depressed people are depressed.”

tweet this

“That’s probably when my depression started,” Craddock says. “Mine’s not as bad as some. I was functionally depressed. I think it’s a natural thing that runs in my family, but at the same time, I think I was not helping myself with my life choices. I did not like living in the boondocks. I did not have a lot of self-respect, because I didn’t have a real job, even though I was doing what I wanted to do — write — and I was getting better at it. I’m an atheist with a Protestant work ethic, the worst of both worlds.” Although he can make light of it now, Craddock doesn’t romanticize that time in his life. “The notion of the depressed artist is ridiculous,” he says. “Depressed people do not do art. Depressed people are depressed. The starving artist does not do work nearly as well as a happy, well-fed artist. That’s just another one of those myths that people buy into, that you should suffer for your art. Suffering doesn’t do anything but make you suffer.”

Things changed for the better in 2000 — or so Craddock thought at first. A small Denver-based company named Write Way showed interest in his most recent work, a fantasy novel called Sparrow’s Flight, and published it that year. The book takes place in a kingdom named Neffrom, which has become threatened by a dark army of supernatural monstrosities. A prophecy-sparked partnership between a noble named Sparrow and a swordswoman name Kisha is the only thing that stands in the way of the unholy horde. Sparrow’s Flight contains prophecies, a reluctant fellowship and many of the other tried-and-true tropes of fantasy fiction. While Write Way wasn’t well known, it was a stepping stone. Until it wasn’t.

“After they published Sparrow’s Flight, they promptly went out of business, because that’s what small presses do,” Craddock says. Write Way entered bankruptcy proceedings, and the publishing rights to the books in their catalogue were sold off at auction. Craddock set out to acquire the rights to his own novel, and he promptly won them — with a bid of one dollar. After fifteen years of struggle, doubt and the painstaking development of his craft, his commercial worth as an author amounted to a buck.

In the meantime, fantasy as a whole was exploding. As Sparrow’s Flight almost instantaneously disappeared, A Storm of Swords, the third book in Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series — the basis for Game of Thrones — debuted on the New York Times bestseller list. Within months, The Fellowship of the Ring, the first installment of filmmaker Peter Jackson’s blockbuster adaption of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, propelled fantasy to dizzying heights of acceptance and popularity. The “stereotypical nerd stuff” in which Craddock had submerged himself since adolescence was now mainstream...though you wouldn’t know it from his career. “David Eddings famously said that the first million words are practice,” he says, citing one of the most successful fantasy authors of the ’80s and ’90s. “And that’s all my first million words were.”

Craddock’s rise from flopped fantasist to acclaimed author began in an unlikely place: prison. He was still living in the hinterlands of Two Buttes when the Write Way fiasco went down, which didn’t help his mindset. But in 2001, his wife was transferred to a new post in Sterling. The town’s population, though only 13,000 at the time, made it a bustling metropolis compared to Two Buttes. The couple bought a house, and Craddock, still licking his wounds from Sparrow’s Flight, resumed his would-be career as a fantasy writer. But after a decade of full-time mythmaking, his lack of anything resembling a steady income began to take its toll on the household. “My wife told me I needed to get a real job,” he remembers, “and I agreed.”

He started working a succession of entry-level office jobs, from tech support to banking. None stuck. Before long, the town’s most prominent employer, Sterling Correctional Facility, became the only option left. Craddock discovered that the prison, Colorado’s largest, was in constant need of educators. As a kid, Craddock had wanted to be a physicist like his father; now he found himself drawn more toward his mother’s general line of work — helping people to overcome obstacles in their lives. Or at least that’s how he chose to view the job. He underwent training to become a correctional officer, then started a new chapter as a teacher of inmates.

“I had no idea how it was going to be, working at a prison, but it was a job,” he recalls. “After I finished my training, they put me with another teacher for a while. I would just walk around from classroom to classroom, asking questions. Then they stuck me in a classroom with thirty guys doing thirty years.” And then something unexpected happened: He discovered he loved it.

“I thrived there,” he says. “Apparently I get along well with criminals. Working in a prison will change you, one way or another. You will either become a much better person or a much worse person. I think I became a better person.”

While working intimately with classrooms full of convicts, Craddock also developed some strong views about the penal system. “The average person on the street believes that once the cops show up and people are arrested, the story is over. The story’s not over,” he says. “Some of them are going to be in the prison system for thirty years. Some of them are going to be there for life. Once you start talking to them and trying to help them, you realize people are just people. It doesn’t matter what they have done. There are very few people who are actually monsters. I’ve met a couple who are actually monsters. There’s just no hope for them. But most of the people in prison have the same interests as everyone else.

“Most of them just lack an education of any useful kind, haven’t read a book since they were a child,” he adds. “But 95 percent of the people who go to prison are going to come back out again. They’re going to be your neighbor. You want them to succeed. This is fundamentally at odds sometimes with what the public wants. The public wants to punish people. How much can you punish someone? If you work at a prison for any period of time, you realize that you cannot punish a human being into good behavior. It shouldn’t be this thing where you say, ‘You have to respect my authority, and then I will respect your humanity.’ You should respect their humanity right off the bat.”

Craddock mostly taught GED classes at Sterling Correctional Facility, though he would occasionally get to teach more specialized subjects such as history, art and, naturally enough, writing. He had spent many years practicing writing as a solitary, insular activity, a way to get lost in the fantastic worlds he imagined. Now he saw it as a doorway through which to re-enter society. “Teaching people to write also teaches them to think,” he says. “One of my heroes is Neil DeGrasse Tyson — all of my heroes are physicists, for some reason — and he said, ‘Know more about the world than you knew yesterday, and lessen the suffering of others. You’d be surprised how far that gets you.’ That’s what I try to do. That’s my job.”

He had found a new mission in life, as well as a new career. But it wasn’t enough to save his marriage. In 2005, Craddock and his wife separated. He moved out of their house and got an apartment in Sterling while their divorce proceeded. Teaching at the prison all day, then writing during the evenings and weekends, he threw himself more passionately than ever — or more desperately than ever — into his novels. “Working, coming home and writing — that was pretty much the sum of my existence for the next eight years or so,” he recalls. He also began getting treatment for his depression. “I would say that getting help for my depression made me more productive overall, to not have long periods of inactivity,” he says. So he became involved in Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers, an organization for area authors both aspiring and professional, and he joined a writing workshop group with established local fantasy authors such as Carol Berg.

Berg, a three-time winner of the Colorado Book Award, says that “the awesomeness of a heroine who enjoys math” was what immediately struck her about Alchemy. The more she read, the more she loved it. “I think it was the incredible depth and completeness of his world: multiple cultures of complex magic, the science and engineering of a world with floating continents, sailing ships and musketeers, all fitting together seamlessly,” she recalls. “I’m still marveling at how he pulls that off.”“The average person on the street believes that once the cops show up and people are arrested, the story is over. The story’s not over.”

tweet this

Back on Earth, Craddock’s life wasn’t as wondrous. Sterling grew as stifling as Two Buttes had been. His requests for a transfer eventually led to a new job at the Denver Women’s Correctional Facility, and in 2014 he moved back to Aurora. Rather than GED classes, Craddock started teaching Computer Information Systems, at last finding a use for the technical training he had received when pursuing video-game design. As with writing, he found a way to use computers to help prisoners develop deeper, more profound strategies that they could use when they got out. “Computers are good for building problem-solving skills,” he explains. “The majority of people I’ve known in prison were there because of frustration. I know exactly what it feels like to be a terrible student. I never complain about what one of my students doesn’t know. I tell them, ‘There is no failure here.’ I just ask them, ‘Do you know more than you knew yesterday?’ That’s my benchmark for progress.”

During this decade-long upheaval, with changes both positive and negative in Craddock’s life, an idea sprouted. He envisioned a world in which continents circled a planet like satellites. Ships sailed not on water, but through the air. And Isabelle, a princess with a maimed hand and a scientific soul, compensates for her lack of magical ability with a keen desire to educate and enlighten the society in which she lives. The seed of the concept that became Alchemy was just one of many Craddock worked on following the dead-on-arrival Sparrow’s Flight in 2000. But something special seemed to be happening in Alchemy.

As he drafted, polished, workshopped and revised the novel, an opportunity arose that would change Craddock’s life. While sitting in on panels and meet-and-greets at the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ annual Colorado Gold Conference in 2012, he found out that a fellow attendee had won a door prize: a one-on-one breakfast consultation with Moshe Feder, an editor at Tor. Feder, a veteran of the industry, had cut his teeth as an assistant editor of Amazing Stories, the first magazine focused exclusively on science fiction, and its sister publication, Fantastic, which was devoted to fantasy. He’d gone on to become one of the country’s most notable sci-fi and fantasy critics before landing at Tor, where he’s edited everyone from current superstars like Brandon Sanderson to such legends as Robert Silverberg.

The chance to pick Feder’s brain and, more important, to pitch him ideas was priceless. As it turned out, the person who won the meeting with Feder was not interested in science fiction or fantasy, so the prize went to Craddock. He couldn’t believe his luck — or the immediate rapport he had with Feder. “I went and had breakfast with Moshe, and we talked about old-school science fiction for three or four hours,” he says. “Then I asked him if I could send him something, and he said, ‘Just send me whatever is most recent.’ So I sent him Alchemy. I knew it was a good book. But this is where it gets weird. He emailed me less than a month later and said, ‘I’m really interested in this book.’”

Feder remembers: “I began reading Alchemy on the flight home from Denver. The well-described, unusual setting, the assured handling of the characters, and the succession of interesting ideas made it obvious that this was work by someone who’d been refining his skills for a long time. It really doesn’t take uniquely editorial perception to know when you’ve been hooked by a good story, and I quickly was. So it was quite an easy decision to try to acquire the book.

“Curtis struck me as friendly, quiet, knowledgeable about the field and serious about his work, someone it would be pleasant to work with,” Feder continues. “But truly, what made me want to read his book was how interesting he made it sound and how intelligently and enthusiastically he answered my questions about it. Given how closely we work with them, it’s great when authors are nice people like Curtis, but in the final analysis, what matters is the quality of the work, and that’s truly where he won my heart.”

The next step was letting Feder sell the idea to the other editors at Tor, but at this point, silence set in. “He disappeared off the face of the earth,” Craddock recalls. “He just, poof, vanished. I couldn’t email him. I couldn’t call him. I didn’t know where he was. I just assumed it was a rejection of absence, which I’d had plenty of.”

Craddock chalked it up to yet more experience, and moved on to the next book idea he had lined up, a superhero novel. “About a year later I got a call out of nowhere,” he says. “The voice on the other end said, ‘It’s Moshe. Sorry I’ve been gone. Are you still interested?’ I looked under my couch cushion to see if there was some other contract I’d forgotten about, but there wasn’t, so I said yes.”

From there Craddock worked backward, counterintuitively searching for a literary agent after he already had a book contract in hand. “I’m used to the absurd,” he says. “I work in a prison.”

The contract came with a stipulation, though it was a welcome one: Tor didn’t only want Alchemy. To the publisher, the book made more sense as the launch pad for an entire series. “They said, ‘Can you do more of these?’” Craddock recalls. He couldn’t think of a reason to say no. Once the contract had been negotiated and signed, he put the finishing touches on the book, handing in the final draft in the spring of 2016.

Alchemy was published this past August. But that wasn’t the end of Isabelle’s story; it was just the beginning. Finally, Craddock possessed a three-book deal from the most renowned speculative fiction publisher in the world. He was a bona fide fantasy author, on the same roster as many of the legends he’d grown up reading.

And it had only taken 32 years.

Isabelle des Zephyrs, cousin to the king of l’Empire Céleste, is not your typical princess. In countless fictional depictions of princesses throughout history, they’ve often been nothing more than damsels in distress. At other times, they’re butt-kicking badasses — an improvement, if not always a more dimensional one. Isabelle is far more complicated, and far more compelling. Shunned by her father for lacking sorcerous talents and the fact that she was born with only one finger on one hand, she publishes academic treatises under the guise of a man and dreams of how she can better her kingdom, which teeters on the cusp of a magical past and a scientific future. She’s betrothed to Principe Julio, son of the king of far-off Aragoth. Rather than fear her arranged marriage, however, she welcomes it as an opportunity — more pragmatic than romantic, perhaps, but an opportunity nonetheless.

“I wanted to do something different with the princess character,” Craddock says. “Basically, I wanted to take the Disney stereotype of the princess and turn it on its head. This is a Cinderella story where Cinderella has agency. On the other hand, I didn’t want to go for the whole warrior-princess thing. Isabelle is a person who lives in a society. She wants social advancement, money, power, all the things she doesn’t have. She has an agenda. I frequently describe Isabelle as a cross between Ada Lovelace and Sherlock Holmes. She wants to build a university. She wants to further education for herself and other people. Throughout the trilogy, she will leave a trail of improved lives that will change the world.”

Craddock shares a passion for education with his creation, but he admits that Isabelle is much better at math then he is. “She has a math brain,” he notes. “She tends to think of things in terms of theorems and so forth.” That talent comes in handy in Alchemy, where almost every facet of life above the planet Caelum is ruled by an involved calculus of atmospheric forces. “The idea of flying ships is really cool,” Craddock is not too modest to admit, “but having sails on something in the air doesn’t actually work.” To make the impossible wonders of Caelum more plausible, he devised a sophisticated system of magic and planetary science that befits the son of a NASA physicist. He even worked out the diameter of Caelum — a piece of trivia that isn’t important to Alchemy but will become pivotal later in the trilogy.“My book is sort of counter, in a lot of ways, to the fantasy that’s being made these days. It’s optimistic.”

tweet this

“The basic idea is that everything moves — everything is in constant motion,” he explains, not really clearing anything up. Part of the pleasure of reading Alchemy, though, is absorbing the details of the world that Craddock has meticulously devised, then assembling them into a mind-bending whole. In that sense, the book is similar to Martin’s sprawling A Song of Ice and Fire, in which the struggles of a single family and their remote northern domain expands to engulf an entire world. Alchemy also boasts many of the other elements that make for popular fantasy: vividly etched characters, suspenseful plotting, violence and romance. But Craddock doesn’t consider himself completely in line with the dominant trend in fantasy, particularly the dark, bleak tone exemplified by Game of Thrones.

“My book is sort of counter, in a lot of ways, to the fantasy that’s being made these days,” he says. “It’s optimistic. The thing about An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors that I wanted to get across was that the characters are not trying to restore some kingdom of the past. These are people who look forward to the future. They have a mindset of progress. Fantasy has always been weirdly conservative. It’s very much about preserving things, keeping things the way that they are. [Alchemy is] like the beginning of the Enlightenment. The dominant paradigm in the world is looking forward to improvement rather than backward, toward some mythical perfection.

“There’s also a lot of fantasy out there that’s nasty for the sake of being nasty, that basically says, ‘The world is a nasty place.’ I remember the era when science fiction was largely hopeful. The future was a thing to be reached out for and embraced, not always a hellish dystopia where all the good things were in the past. I’m gambling on the idea that people are going to want to read something fun. Where friendship and fellowship and all those things matter. Where people can improve the world rather than simply slow the bleeding. Where the heroes can confront monsters without becoming monsters. I hope this can be a bright book in dark times.”

Curtis Craddock will be at MileHiCon at the Hyatt Regency Denver Tech Center from Friday, October 27, through Sunday, October 29; he will speak about fantasy on various panels and sign copies of An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors. Find out more at milehicon.org.