At the start, Hedwig and the Angry Inch seems like a hipper, wilder, more raucous and contemporary variation on a theme that's been around since Lanford Wilson's The Madness of Lady Bright in the '60s: the loneliness and ultimate psychic disintegration of a gay diva. But the show soon sets out its own markers and expresses its own worldview. Author John Cameron Mitchell — son of an intensely religious military family from Colorado Springs — has significant things to say about love and violation, loneliness and loss, and the ineffable yearning most of us feel for the half-known, half-sensed thing we believe will complete us.

What you get is an hour and a half of speech and rock song so seamlessly woven together that, looking back, you're not sure exactly what was spoken and what was sung. The framework is provided by "The Origin of Love," a song that evokes Plato's vision of how sexual congress began. Once the world was filled with twinned creatures, both parts male, both female and androgynous, but they were severed by Zeus. Now, bloodied and butchered, these half-creatures search the world for their lost partners. Hedwig began as Hansel, born in East Berlin to a GI father and a German mother, a lost boy who gave blow jobs to soldiers for candy and attention and was eventually seduced by the tawdry glamour of the West: the scent from a McDonald's on the other side of the wall, the sweet, soft chewiness of American gummy bears. When a GI called Luther wanted to marry him and bring him to the United States, Hansel's mother lent the boy her name and passport and arranged for a sex-change operation. But the operation was botched, and Hansel, now Hedwig and literally bloodied and butchered, was left with an inch-long stub, neither fully male nor fully female. A year later — ironically, on the day the Berlin Wall fell — Luther left Hedwig alone in their trailer in Kansas. She eventually seduced the teenage son of a fundamentalist Christian military family and came to love him. But he, too, abandoned her: Using the name she'd made up for him — Tommy Gnosis — and the songs she'd written, he became a rock star.

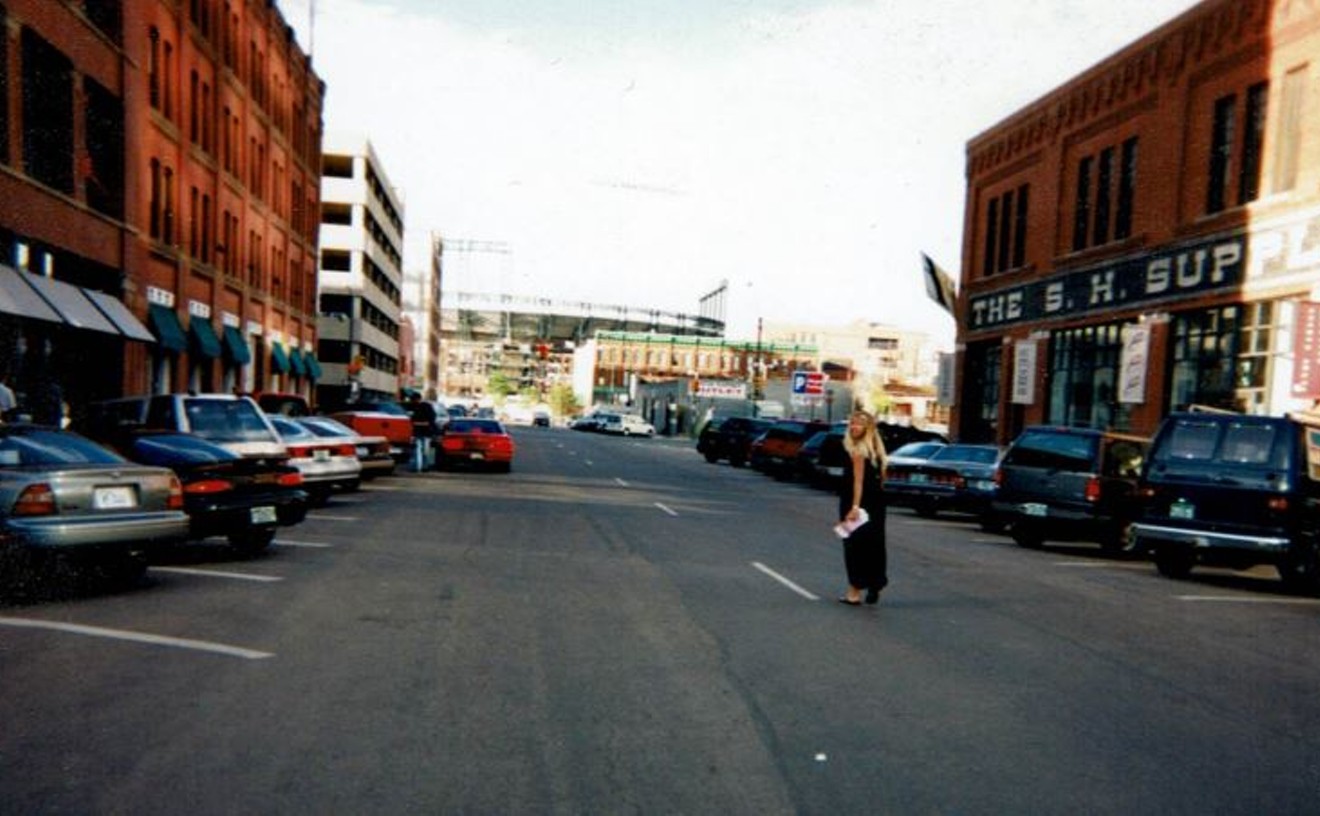

Now, while Hedwig performs at the Avenue Theater, backed by her band, the Angry Inch, and Yitzak, the ambiguously sexed person she refers to as her husband and whom she first met in Serbia performing under the name Crystal Nacht, Tommy Gnosis enjoys the noisy adulation of fans at the Pepsi Center. Periodically, Hedwig lets us hear the roars of applause from there, and they underline her exile, her profound loneliness. The reference to the Berlin Wall is in some ways a fairly straightforward metaphor for Hedwig's plight: She straddles countries and realities as well as gender. But, like the mention of Kristallnacht, it's more than that; it's a reminder of the casual brutality of a world where many children struggle for physical and emotional survival, begging, selling themselves, killing — whatever it takes — and those who fall outside certain social or economic boundaries endure lifetimes of bitter struggle.

The music, by Stephen Trask, is varied and exhilarating, the dialogue dark, smart and funny, and the Avenue production purely terrific: Amanda Earls as an alternately sulky and animated Yitzak; the band of Scott Smith, Austin Hein and John Olsson, led by David Nehls; Kevin Copenhaver's costumes. But everything rises and falls on the title role, and you don't want to miss Nick Sugar. He doesn't take to the Denver stage nearly often enough, but every one of his performances over the last ten years is firmly lodged in my memory, from the epicene emcee of Cabaret to his funny-forlorn Bat Boy. I knew the man could strut. I knew he could cross-dress. I knew he could hold an audience's unflinching attention for an entire evening, and at the end you still didn't want to let him go. But the role of Hedwig is the one he was born to play, allowing not only irony, satire, sexiness and self-possession, but the kind of emotion for which an actor reaches into the depths of his being. Yet Sugar manages to do the entire falling-apart-don't-belong-anywhere trope without a trace of self-pity. There's a toughness at the core of his Hedwig, even a kind of dignity. Which fits, because the show isn't just the long, lurid, dramatic fall I'd anticipated, but an affirmation as — at the end of a boundary-breaking evening — Hedwig and Yitzak finally discover their rightful forms and the audience rejoices with them.