But then, farce is often nasty. It depends on deception and embarrassment: Characters pretend to be better than they are and then try to avoid being caught in the act of being themselves. Farce also depends on dizzying speed--a lot of rushing around, slamming doors, fast line readings and quick retorts. Speed is hard to achieve on stage--harder than in the movies--but its force is usually intended to knock down human pretense.

Playwright Jeffrey Hatcher was commissioned to adapt Le Dindon for the DCTC, and it wasn't easy. The play was first translated by Michaela Fisnar, who saw the turn-of-the-century tale in terms of Hollywood shenanigans. But most of the jokes didn't translate into English at all. So Hatcher rewrote the script.

"My first problem is that Hollywood is known for its hedonism, for its overt sexual behavior," Hatcher says in an interview. "So I thought, if you're going to do a farce in which people are pretending to be dignified but are having it off everywhere, the best period in Hollywood would be during the period of the Hays office [the Production Code's stuffy thought police], when people were pretending to be more upstanding and moral than they actually were."

Hatcher updated the characters to the 1930s but kept the basic plot intact--characters enter and exit the same way, slam the same doors and hold the same positions in Hatcher's version as they do in the original.

"The first thing you have to do is not change one bit of the plot or the structure, because the Feydeau plot works," says Hatcher. "But only about 40 percent of the dialogue translates." So the rest had to be invented. There are punchlines that work in any language, he says, but there are many more that simply don't.

As produced by the DCTC, the story concerns a young Kansas City couple who comes to big, bad Hollywood to "make a difference." The husband has been put in charge of the Production Code office and is enforcing the rules (no branding of humans or cattle, lovers on film must keep one foot on the floor at all times, etc.). Right away, there is a squabble with the studio chief. And very soon, censor John Johnson (played with genuine finesse by Mark Shanahan) is confronted by his own recent past in the form of a South American vamp, La Vita Terrafamilia (Isabel Keating, who is just not funny enough). She threatens to kill herself and leave a note explaining why if he doesn't sleep with her again. Caught like a rat in a trap, he agrees to meet her that night at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Meanwhile, his lovely wife, Betty, is pursued by horny movie stars Rod Larue (Anthony Dodge in a Clark Gable sendup) and Larry Fontayne (Walter Hudson doing Errol Flynn). Betty vows that if she ever finds out her husband has been unfaithful, she will avenge herself in an affair. So Rod Larue plots to catch her husband at it with some starlet.

There are a number of goofy subplots: a jealous studio exec; a hypercritical, self-righteous congressman with a deaf wife whom he despises; a Jean Harlow-like bimbo who pursues a variety of lovers; a Marxist maid (a howler performance by Rachel K. Taylor) who self-righteously denounces the upper classes; and a terrific Gabby Hayes butler (Noble Shropshire is dead-on) who looks after Fontayne.

The funniest bit concerns Larue's hard-drinking, smart-mouthed wife, Mayo Larue, meant to be a Barbara Stanwyck tough girl. Jacqueline Antaramian gives the best performance of the evening (and one of the best of the season) in the role. Dressed as Scarlett O'Hara (she's auditioning for the role), Mayo cracks wise with lines from Gone With the Wind and barbs every comment with sardonic world-weariness.

"We played off of what the audience generally knows about the Hays office," says Hatcher. "They generally know that there were a bunch of censors who wouldn't let people say certain things or do certain things." Hatcher believes that farce still works because every twenty years or so, some new moralistic bubble of hypocrisy arises that needs to be pricked. Whether it's on the right or the left doesn't make any difference. One could make a pretty funny farce about the Lincoln bedroom or televangelists or Newt Gingrich, he says.

But the question is, why not go for the government instead of a Hollywood that just doesn't exist anymore? Hollywood may be a cesspool, but it's also an open tank. And the Hays office, for all its faults, managed to let some of the greatest Hollywood films ever made squeak by its inspections. There are those who might argue that the Production Code actually stimulated greater creativity. This show's approach to farce just doesn't hang together.

But then, despite the DCTC's best efforts, farce is just too hard to do well these days. As Hatcher himself points out, so much of today's behavior is so overt that it's hard to skewer as farce. What with all the gut-spilling on daytime talk shows and public figures like Gary Hart tempting the press to follow him, it's more the stuff of satire a la Saturday Night Live than pure farce.

One Foot on the Floor is a major effort--a luxurious, expressive, clever adaptation that, when all is said and done, seems rather pointless: All that creative energy might actually have been better employed in the service of worthier, funnier material.

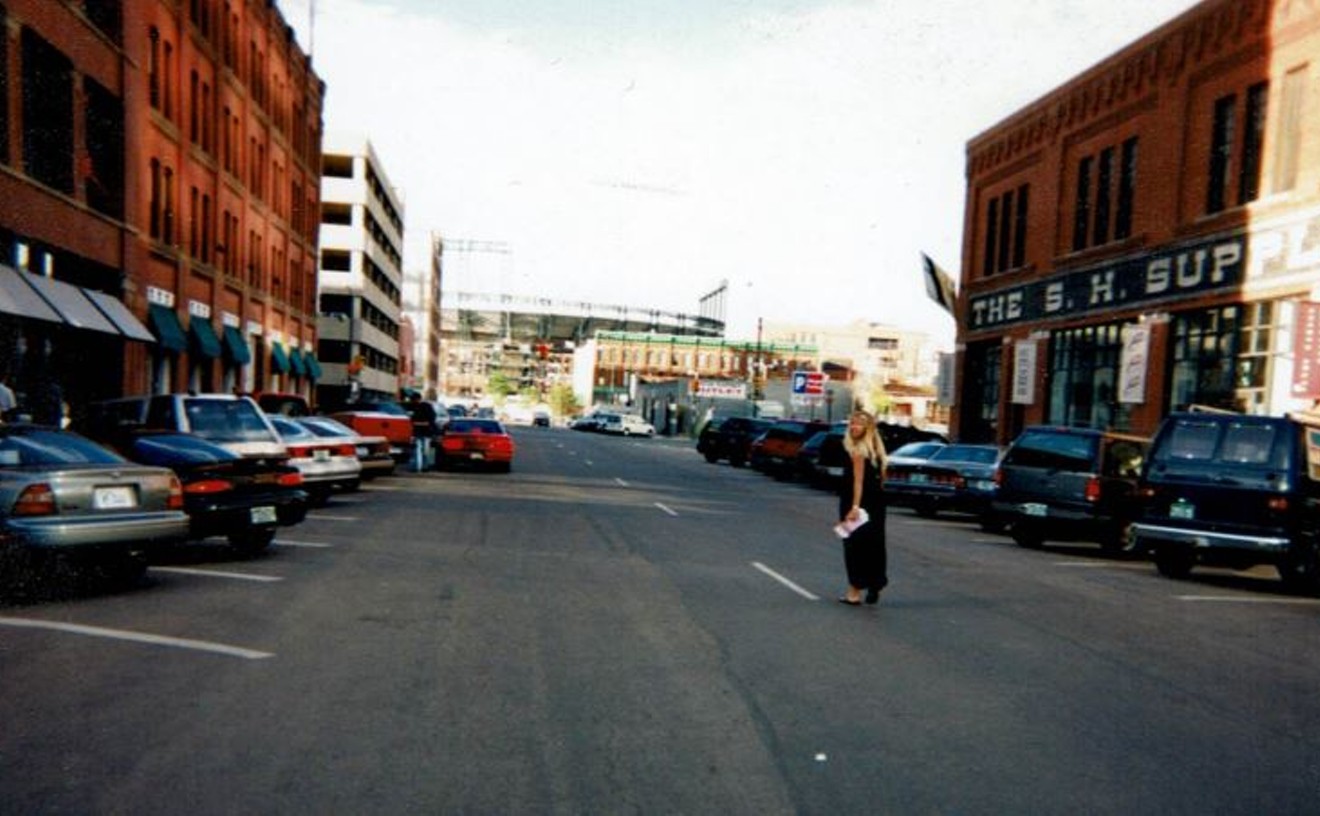

One Foot on the Floor, at the Denver Center Theatre Company, at 14th and Curtis in the Plex, through April 19.