Under the steady direction of Verl Hite, the Bug's shoebox moviehouse space proves an appropriate environment for a drama that skewers Hollywood's slimy dream-hawkers by using a few well-worn show-business devices; arch melodrama, stock characters and cheesy background music are all significant players in Shepard's sly send-up. In fact, a few scenes after we're introduced to Wheeler (Terrence Shaw), the absent-minded genius of a mythical West Coast dream factory, the irascible old man undergoes a startling transformation. Reflecting both Los Angeles's sand-and-concrete desert environment as well as his character's reputation for reptilian duplicity, Shaw assumes a lizardlike appearance in Act Two, painting his face with green makeup and clawing the air with his bony fingers as he hisses, "We can re-create the world and make you swallow it whole."

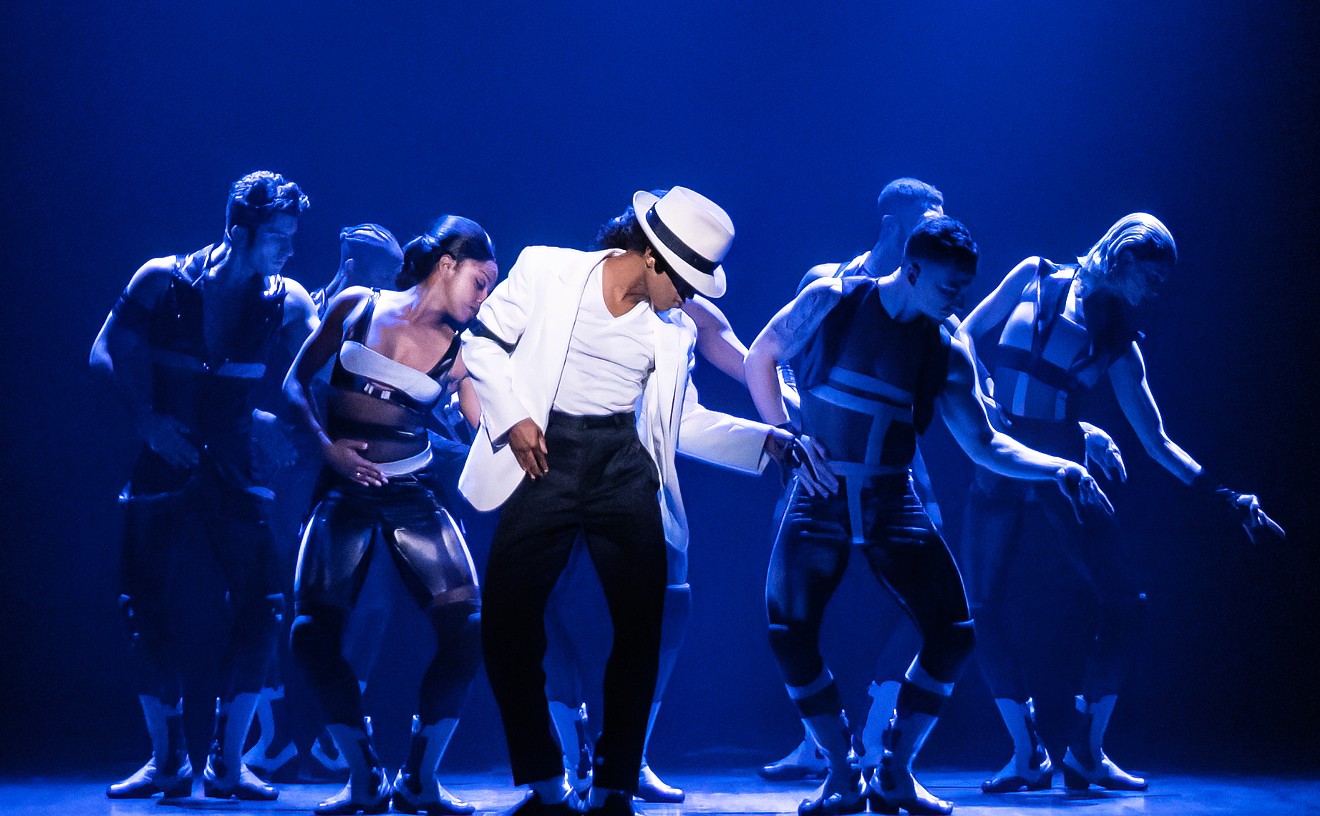

Naturally, Wheeler's arrogance doesn't sit too well with Rabbit Brown (Alex Weimer), a straight-shooting, buckboard-riding stuntman (and fledgling script doctor) who's been hired by Wheeler's fast-talking underling, Lanx (J. Heston Gray), to pump some verisimilitude into Wheeler's latest disaster of a project. Noting that Wheeler's movie lacks a richly drawn--or believable--main character, Rabbit agrees to undertake a revision of the film. But, Lanx informs him, there's a catch: Rabbit must achieve his Herculean task in collaboration with two of Lanx's hangers-on. The amiable Rabbit (who saunters about the stage dragging four furry pelts attached to his belt) seems confident enough to take on the project by himself. Nonetheless, he holes up in a climate-controlled office with Tympani (Gary Culig), a wannabe jazz drummer who's forever in search of the perfect rhythm, and Miss Scoons (Tracey Swerer), a blond, leggy secretary who approaches menial tasks with ardor and daunting ones (like making a great film out of drivel) with nonchalance. From time to time, the trio's efforts are accompanied by the live, improvisatory jamming of a strolling saxophone player (Tommy Liehe).

Aided by some garish special effects, such as a backlit movie screen that changes colors to reflect the dynamics of each scene, the performers do their best to navigate the dramatist's undulating psychological landscape. Employing a straightforward delivery of expressionistic soliloquies and near-farcical dialogue, the actors mostly succeed in rendering the complex mate-rial without overtly commenting on it. Swerer in particular articulates Miss Scoons's far-flung musings with admirable panache. Deftly locating the misplaced floozy's uncluttered critical sense ("Nobody knows what's good anymore...You just gotta rely on your own intuition"), Swerer also finds Scoons's capacity for artistic insight, quietly observing that most people never bother to "look the city in the eyes anymore; people [just live] in dreams." As the transmogrified Wheeler, Shaw rises to the occasion in the second half of the drama, spewing venom and striking at the heart of Hollywood moguldom as he declares, "I wanted to make an industry of imagination. Now look at it--poisoned, putrefied." Despite the fact that Weimer's Rabbit is more of a bemused bystander than the droll iconoclast that Shepard likely intends, he exudes--as does Culig--a fervent idealism that bespeaks an artist cradling some yet-to-be-shattered illusions. And although Gray's portrait of the slick studio executive lacks sharpness and dimension, he still lands a few punches when he delivers his character's obtuse observations about the creative process.

However, a couple of crucial expository scenes, which are underscored by live music, wind up being more cacophonous than revelatory. In addition, during several episodes when the actors affect a deadpan delivery, it's not always clear whether they're addressing the audience directly, giving public voice to inner thoughts, or merely fishing for their lines amid Shepard's rapidly flowing stream of consciousness. And, at the top of Act Two, when the actors sport costumes reminiscent of Hollywood stereotypes--Swerer dons a nun's habit and scrubs the stage floor, Gray wears prizefighters' trunks as he shadowboxes in a corner and Culig, clad in a short-order cook's uniform, flips imaginary fast-food items with a spatula--Shepard's 100-minute, convoluted tale becomes even more difficult to follow.

Even so, Hite and company nicely convey the idea that today's entertainment industry is no longer a diversionary sideshow, a creature comfort or even a special exhibit confined to a remote corner of life's zoo--it's somehow mutated into an overgrown, often-grotesque stepchild. As Shepard was brazen enough to suggest 23 years ago, movies and their mass-merchandised by-products, much like the green slime that Wheeler and Rabbit encounter at play's end, have managed to slither into every corner of our ultra-wired existence.

Angel City, through June 26 at the Bug Performance and Media Art Center, 3654 Navajo Street, 303-477-9984.