Back in 2005, Westword writers spread out along Broadway, sending in dispatches to document how the street was changing. A dozen years later, Broadway is still booming, many of its blocks bustling with business, traffic and development. But the more things change, the more they stay the same — and as our writers discovered on a recent rerun of our Broadway exploration, traveling along this great thoroughfare is still a real trip through Denver's past and future.

The First Avenue Hotel, designed by architect William Quayle and built by the Flemming brothers, opened in 1906 in the heart of Denver, at 101 Broadway, one of “two great thoroughfares” planners had mapped out just four decades earlier for this new city at the edge of the plains.

Broadway marked the eastern border of the original congressional grant that officially set aside 960 acres (at $1.25 per) for Denver in 1864; the street stretched from Cherry Creek up to 20th Avenue, where it ran into downtown’s off-kilter grid. As the city grew, boosters pushed Broadway in both directions, up past the stockyards and rail yards to the north, down along a “Miracle Mile” of auto dealerships and other commercial ventures and then through sleepy farms to the south.

But the street’s heart has always been at the center of the city, in the blocks where north and south meet. And as Denver has gone from boom to bust to boom again, it’s been reflected in the boom and bust of the businesses along Broadway — including the First Avenue Hotel. Like the once glorious Webber Show, a theater at 119 South Broadway that boasted the first air-conditioned auditorium in the city, the magnificent, neo-classically inspired building had fallen into disrepair by the start of the millennium. By then, the Webber was an outpost of Kitty’s, an infamous stroke palace, and the former luxury hotel an unofficial flophouse. Business in the area has exploded over the past few years, though, with new ventures taking over every available storefront and home prices in surrounding Baker soaring; the Webber building is now on its way to becoming a distillery. And the First Avenue Hotel? Zocalo Community Development plans to return it to at least some of its former glory, with plenty of upscale retail — but also 106 affordable apartments, a rarity in this part of town where they were so plentiful two decades ago.

Zocalo was in front of the Denver Landmark Preservation Commission on June 6, to talk about plans for the structure that it plans to construct behind the hotel, designated a landmark three decades ago, when no one could have predicted how Broadway would boom again. It’s just one of many landmarks — official and otherwise — along this great thoroughfare, just one of the many stories on Broadway. — Patricia Calhoun

Mickey’s Top Sirloin

6950 Broadway

Whoever had the bright idea of rebranding Brighton Boulevard as Broadway North, or North Broadway, or NoBroNo, or whatever the hell they’re thinking about calling it these days, apparently forgot that there’s already a Broadway heading north at some remove from the RiNo hubbub. It plays peek-a-boo with Interstate 25, serving as a kind of intermittent frontage road, before petering out in the soulless suburbs north of the Boulder turnpike. Just a few blocks shy of its end, though, it reaches its apotheosis in a sprawling green, glorious roadhouse beloved by generations of north Denver and Adams County residents who value good eats over fancy-pants hoot cuisine.

Although the current building dates back only to 2005, Mickey’s Top Sirloin has been serving up steaks, Mexican food and old-school, red-sauce Italian fare on the same corner for more than half a century. Mickey Broncucia’s grandfather grew vegetables here; his dad ran a grocery store here. Mickey started a restaurant next door to where he grew up and never looked back.

After rising early every day for decades to get things ready for the lunch crowd, Broncucia recently sold the operation to Trace Welch — who, much to everyone’s relief, has refrained from making any sweeping changes to the bill of fare or the prices. The place has the kind of neighborhood feel that only decades of hard work and loyal patronage can achieve. At Mickey’s, truck drivers rub shoulders with county officials in suits, the waitresses call you “Sweetie” and “Hon,” and the guy on the next bar stool just might be the king of a gravel-pit empire or the top prosecutor of the 17th Judicial District.

Mickey still shows up regularly here, nodding at the regulars and chatting up the staff like he owns the place. There’s a bocce court on premises for the curious and the hard-core; the top sirloin costs eleven bucks. You just don’t mess with what works, especially if it’s been working for a long, long time. — Alan Prendergast

I-25 Exit Lane

500 South Broadway

In the late 1880s, Broadway and all of Denver was at a crossroads. As electricity started coursing through the city, cable cars were slowly beginning to replace horse-drawn streetcars. The Denver Tramway Company wanted to build lines for its cable cars along Broadway, the thirty-year-old city’s main drag, but the Denver City Railway’s horse-drawn line already ran down the middle of the street. The battle resulted in an awkward win for both companies: The horses remained, flanked by cable lines.

Come November, Denver residents could determine the winner of today’s version of that battle: cars, and everyone else.

In the upcoming election, voters will decide on a yet-to-be-finalized bond package that could, among many other projects, transform Broadway’s five lanes into three for cars, one for 24-hour bus transit and one for a two-way bicycle lane.

Faced with a population boom that saw an average of forty people moving to Denver every day between 2006 and 2014, the city has sought to alleviate pressure on its busiest thoroughfares. In September 2015, it launched the Denver Moves Broadway/Lincoln Corridor Study. The goal was to find ways to maintain room for car traffic and provide additional, safer mobility for bike commuters and pedestrians along Broadway between Colfax Avenue and I-25, says Emily Snyder, Urban Mobility Manager at the Denver Department of Public Works.

After collaborating with businesses in the area and hosting community workshops, Denver launched a pilot two-way bike lane on Broadway between Bayaud and Virginia avenues in August 2016. Between August and November of last year, the city collected data that showed people felt safer walking and biking in the study area. More bikers were using the lane instead of the sidewalk and street, and 61 percent of respondents thought the bike lane should be expanded to downtown.

City planners took those findings into account as they proposed a complete, $22 million redesign of Broadway, which a subcommittee working on the bond project approved. But early this month, an executive committee tasked with fine-tuning the package for Mayor Michael Hancock allotted only $12 million to the Broadway corridor, just enough to fund improvements to walkways and a two-way bike lane and 24-hour bus lane from I-25 (Virginia Avenue, more specifically) to the Cherry Creek Trail. Whether the project is fully funded or not, it’s “still a meaningful connection from a bike connectivity standpoint,” Snyder says.

If the bond ballot measure fails, Snyder says, the city will find alternative sources of funding for the Broadway project, which could one day stretch from from I-25 to Colfax. “The full vision is $22 million,” Snyder says. “If we have to build it in segments, we will pursue that course.” In the meantime, the two-way bike lane has so far reduced crashes on Broadway, a street that sees a lot of them, and has only increased average time in traffic for cars by nine seconds. — Ana Campbell

Boyztown

117 Broadway

When Randy Long bought Boyztown in 2005, the gay male strip club — which had gotten its start as a speakeasy back in the ’20s — had a drug problem. So Long’s first task was to rid the place of drugs, and he didn’t rely on his bouncers or the cops: He did the dirty work himself, telling people that drug use would no longer be acceptable at his joint. He wanted to create a relaxed neighborhood spot, a place where friends could gather, admire the dancers and cruise comfortably.

But now, some customers say, Boyztown has a new problem: bachelorette parties.

Like many gay bars around town, the club is seeing increasing tension between gay men who want their gay bar to stay gay, and straight women who flood the places when looking for a good, safe time. Because it’s a strip club, Boyztown has become a major draw for bachelorette parties, where drunken women gawk at — and sometimes grab — the dancers, some of whom identify as straight. “The straight ones we’ve had, they eventually have traveled to the other side of the fence and try it,” says Long. “We live in a day and time where more people are respectfully fluid.”

That flexibility is something Long embraces at Boyztown. He welcomes everybody, gay or straight, including bachelorettes. He’s happy to have them, he says, and their money helps keep the bar open even as so many similar clubs struggle to stay afloat. “In the day of equal rights, you cannot take a discriminating stance, and I would never do that with anybody,” Long says. “For the most part, the bachelorette parties are only here for an hour to an hour and a half, and then they go on bar-hopping.” To balance things out, Boyztown has started charging a “table reservation fee” of $5 a head for bachelorette parties and only bachelorette parties, to make sure both the bar and the drunken women are benefiting from the relationship. In turn, the bar often sends the groups free shots. Much of that money helps keep the place running, but some of it goes to good causes like two gay softball leagues that Long sponsors and the Gay Men’s Chorus.

Boyztown has seen the impact of gay-cruising apps like Grindr and Scruff — not to mention the fight for marriage equality — making it increasingly less necessary for people to go to gay bars in order to meet potential partners. And then there’s recreational marijuana: Long fears that legalization will mean more people spending money on cannabis and less on booze. But the biggest hit to Boyztown’s business has come from the rising cost of housing in Denver. “That’s zapping people’s disposable income to go out as often as they used to. I hear people talking about that all the time,” Long explains. “People we used to see three times or four times a week, we see two times a week.”

Long thinks other gay bars are struggling to get by because they’re diluting their vision, trying to keep up with a changing market. “People are looking for the excuse of why their brand might be failing,” he says. “What I see from a corporate standpoint is this: They’re changing their brand, which confuses the customer.”

Long has no desire to change, because male dancers and a neighborhood-bar atmosphere make Boyztown timeless. Even if people can cruise online, they can’t check out live, buff men dancing on a pole. And no number of social-media apps can take away the pleasure of people congregating in an unpretentious space. “We try to have a fun place that’s reasonably priced and no matter what walk of life you come from, you’re welcome here,” Long says. “We just want everybody to respect everybody.” — Kyle Harris

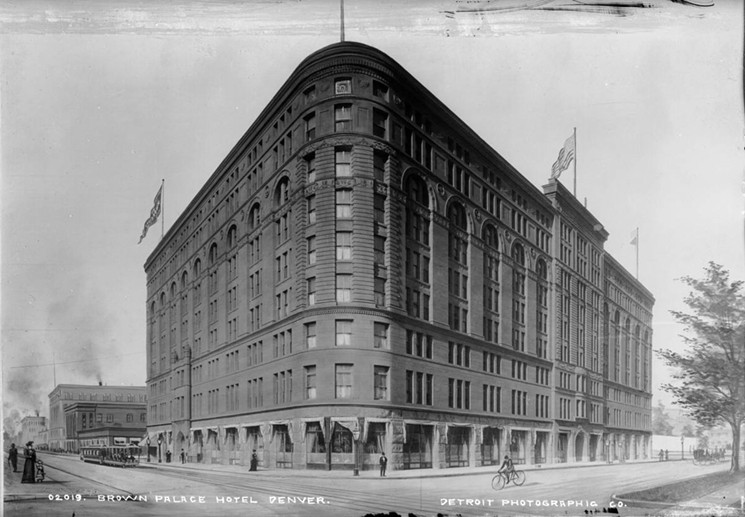

The Brown Palace

321 17th Street

The Brown looms imperiously over Broadway, a granite-and-sandstone fortress that aspires to rise above all that’s out there. You can’t even get into the place from the Broadway side; the formal entrances are on Tremont and 17th streets, as if to protect guests from the chaos and contagions of Denver’s main drag.

Such snootiness was doubtless what carpenter-turned-real-estate-tycoon Henry C. Brown had in mind when he began planning a grand hotel at this prime location, at the gateway to downtown and just a few blocks from the Colorado State Capitol (a project for which he’d shrewdly donated the land, in order to boost the value of his other holdings). For most of its history, the Brown was virtually the only opulent refuge in town worthy of stashing visiting presidents and royalty, movie stars and Beatles.

These days, of course, the luxury market in this toddlin’ town is roiling with cutthroat competition. But the Brown, which is celebrating its 125th anniversary this summer, is holding its own. Nothing quite says “class” like a visit to its majestic, eight-story atrium, a teeming display of filigreed wrought iron capped by a stained-glass skylight; just gliding into the scene feels like a giant step back to a more elegant age. And the perfect time to visit is the cocktail hour, when the rituals of the hotel tend to melt away the cares and headaches of the bustling world out on Broadway.

The sense of tradition is stronger in some areas of the hotel than others, though. The iconic Ship Tavern recently endured a renovation that ditched some of its nautical touches for a frat-boy-diner look. High tea is still served in the atrium, complete with elaborately uniformed help and cornball show tunes on the piano, but the effect is somewhat diminished by the relaxed dress code and general slobbiness of the clientele. (Dude, a grimy T-shirt for high tea? Get a clue.)

To truly appreciate what makes the Brown so special, so palatial, head to the cigar bar, Churchill's. A clubby, leather-and-marble den of execs and entrepreneurs, it’s long been recognized by regulars as an invitation to turn off your cell phone, elude your underlings, and savor a high-priced stogie and a Scotch. The smokes are available from a custom humidor, the Scotch one of an impressive array of single-malts that will leave any captain of industry feeling like the laird of the croft.

Out on the streets, marijuana might be the drug of choice, but in here the waft of tobacco has a forbidden cachet. With a total absence of irony, a middle-management type puts on his Indiana Jones hat and heads for the door. Others nod or wave at him, then return to their smokes, drinks and conversations. A psychologist might wonder why folks with money to burn would choose to do so in such a conspicuous yet insular place, but Henry Brown had it all figured out: Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. — Alan Prendergast

Little Brown House

1995 South Broadway

Every neighborhood in Denver smells like herb from time to time, but certain parts of town will always be skunkier than others. Park Hill, Stapleton and Montbello are prime examples, because of all the growing operations east of Havana Street and north of I-70. Federal Boulevard and East Colfax Avenue have almost as many pot shops as they do dive bars now — and that’s saying a lot. Still, none of these neighborhoods have quite the reputation that South Broadway does.

Some people call it Broadsterdam, others call it the Green Mile. But on most days, Anita Bear just calls it work. The owner of the Little Brown House has been on the job from the early days of medical marijuana dispensaries, and she’s watched this strip of Broadway undergo a heady transformation. “It really stretches from south of the I-25 exit all the way to Englewood,” she says. “But it’s really dense over here because these licenses were issued before the 1,000-foot rule.”

A rule adopted by Denver in 2013 prohibits any new dispensary from opening within 1,000 feet of another dispensary, school, daycare or drug treatment center. Now that there are eighteen dispensaries on South Broadway, finding a new spot on the Green Mile is tough, so Bear opened another store off I-70 at East 48th Avenue. “You can’t get that homey, neighborhood vibe off the freeway,” she acknowledges. “It helps to be down here, because people think of this area for going shopping, and there’s a lot of foot traffic for other things to do.”

That foot traffic wasn’t as heavy ten years ago; everyone kept to their cars. What changed this stretch from a pit to a respectable place for commerce? Pot, according to Luke Ramirez, former owner of Walking Raven, a dispensary next to Little Brown House. In 2009, the Department of Justice released the Ogden Memo, assuring patients and dispensaries in states where medical marijuana was legal that they would not face federal prosecution if they obeyed their state’s laws. That led to a boom of dispensaries in Denver; Ramirez and his partners were among the first to open up shop on South Broadway.

Trying to convince a landlord to lease his team a building was tougher back then, Ramirez recalls, and Walking Raven had to pay significantly above market price to secure a spot. But once landlords realized all the money that marijuana was bringing in, they changed their tune. “The area was kind of dead back then. It was right at the end of the real estate crash, and our landlord was hurting. A lot of the buildings were empty,” Ramirez says. “Very shortly after we opened, like three to six months, all the other shops popped up. The place just blew up in a four-and-a-half-month window.”

In 2010, Ramirez took over operations of Walking Raven, which gave him a firsthand look at South Broadway’s transformation. He recalls names like Dr. Reefer and Herbal Alternatives on pot shops that are no longer around from the early, grittier times. “I still remember witnessing robberies and some pretty serious crime close to our doors,” he says. “Now I see some young girl jogging with her dog on the same street.”

He sold his ownership of Walking Raven in 2016 and opened a new dispensary in the Platt Park neighborhood, where he’s more likely to see a Mercedes outside than broken bottles. Still, Ramirez looks back on his South Broadway days with pride and affection. “The level of cooperation with all the stores was awesome. We were competitors, but we were all helping out each other with compliance, ruling issues, changes and testifying to the city,” he recalls. “Look at a picture in 2008 and look at it now. We saved that area in a lot of ways.” — Thomas Mitchell

Famous Pizza

98 South Broadway

The opening credits of comedian Louis CK’s television show, Louie, follow the main character ducking into a New York City pizzeria, wolfing down the better part of a slice while standing in the open doorway, then discarding the crust before hurrying out. The sequence could easily have been filmed in the entryway of Famous Pizza, an institution in Broadway’s White Palace building since 1974 — only no customer at this Denver pie shop would ever consider chucking even a single bite of pizza before leaving.

Sure, Broadway denizens never seem to sit still for very long, whether they’re catching a bus, meeting a friend at one of the strip’s many bars or just striding with intent (if perhaps no destination) down the busy sidewalk. But the beckoning aroma of charred flour and bubbling sauce has the same effect as an Italian nonna gesturing to an open seat and intoning, “Sit, eat!”

Gus Mavrocefalos opened this Famous Pizza outpost (the name was a boast back then, but it’s simply a statement of fact now) 43 years ago; not much has changed in the intervening decades. The floors are a little worn and the mirrored tiles along the walls and counters, once swank and ritzy, now seem quaint and kitschy — the kind of decor modern designers attempt to emulate as “retro.” Racks of fresh-baked pies behind glass, lined up right to the front window of the store, await buyers, while cooks busy themselves stretching dough or pulling pizza from the oven decks behind them. Whether you’re on Broadway in Denver or in New York, the scene is familiar. Whole pizzas are boxed for takeout and individual slices are slapped onto paper plates; one old-timer who may have occupied the same chair since the restaurant opened watches TV in the back. At the counter, the occasional spaghetti or calzone order changes up the rhythm just a little, but otherwise time ticks on much the way it has for years — at the analog pace of the minute hand extended across the white face of a clock, and not the scattered punctuation of digital timekeeping, making every second seem lost the moment it blinks in and out of existence.

Newer pizzerias peddle pie by the slice until after last call; the Pie Hole just up the street and Fat Sully’s across Broadway draw hungry bar-hoppers out well past midnight like moths to a porch light. But Famous is closed by then, even on the weekends, and during the week the door is locked at 10 p.m. During the day, though, this is the best place in town to grab a slice to go, then eat it while you walk along Broadway, elbow high to keep a rivulet of grease from running down your forearm (and to fence out oncoming pedestrians). But grabbing a seat inside the immaculately clean joint is a much better way to taste the mingled flavors of cheese, pepperoni and the history of the Broadway drag. — Mark Antonation

Englewood Grand

3435 South Broadway, Englewood

The bar Phil Zierke owns has only been around for a year and some change, but it already has regulars. He points to a couple drinking cocktails at the far end of the bar and says they own the frame shop across the street. But this being Englewood, a city historically in the middle of here and there that now has a light-rail line running down its western border, he sees a lot of newbies, too. The couple from Castle Rock he just closed out were on their way to a concert at Red Rocks.

With few options for well-stocked watering holes, Englewoodians, if that is such a thing, were thirsty for a comfortable, low-key place to get a nightcap. With its dark wood walls, long bar and cold beer from the best breweries in metro Denver, the Englewood Grand became a neighborhood draw almost overnight. Yes, sir, business has been good.

Phil grew up in Nebraska, watching whatever baseball and football games the local TV stations would pick up; maybe forgoing loyalty to any team is one reason he’s so easygoing. He’s a bartender in the classic sense: genuinely friendly, instinctively knowing when to offer re-pours, and talking passionately about his bar, from the popcorn machine he brought all the way from the VFW in his home town to the neon sign outside that his four-year-old ceremoniously switched on for the first time a few weeks ago. Phil’s been in the neighborhood since ’96; he and his family live four blocks away from the Grand, less than a mile south of the Englewood-Denver border. In 1865, homesteaders created Broadway, the first legal road heading south from Denver. Englewood sprang up along the way and was incorporated in 1903; Broadway was paved 22 years later. Now 32,480 people call Englewood home, and that number is growing. In just the last year, the median sale price for homes here rose from about $330,000 to $385,000.

From the bar that he and two friends tend, Phil has seen recent changes play out in real time. The new apartment building going up behind the Englewood Grand seems to have driven out the drug addicts who used to load up and loiter in the area, just blocks from a light-rail stop, a library and a Walmart. Though car traffic seems to have gotten more congested on South Broadway, foot traffic is still light. Phil reckons that will change by the end of the year, after four restaurants that are in the works all open on the block.

Phil’s excited about Englewood’s changes, but he’s committed to maintaining the friendly, small-town feel of this city born from Broadway. When a stranger from Denver stops in and chats with him for a while, he ends up giving her a neighbor’s discount. That’s just what Phil does. — Ana Campbell

Buffalo Exchange

51 Broadway

When a former burlesque performer came into Buffalo Exchange to sell the thrift store clothing and other accessories, staffer Greg Maronde figured he might find some good stuff. His interest only increased when he spotted some black feathers protruding out of a box. Then he noticed a couple of heavy chains. And when he finally pulled the item out of the box, he found himself staring face to face at an intricate leather horse head with feathers forming its mane and chains attached to it for whatever bondage or fetish activities its wearer desired. “I really had a ‘holy fuck’ moment, thinking, ‘What an amazing piece!’” Maronde recalls today.

The store immediately bought the horse head, which was sold to a customer the very same day it was put out on the floor.

“The really fantastic pieces fly out the door,” Maronde says, explaining that Buffalo Exchange can have upwards of 300 people coming in daily to sell items to the store, for which they receive cash (30 percent of Buffalo Exchange’s resale price tag on the item) or store credit (50 percent of the resale price tag).

Located right in the Baker neighborhood, Buffalo Exchange is largely emblematic of the young, trendy demographic that’s settled here. The store opened its doors in December 2011, and it continues to get busier each year. “I think we’ve become a center not just for the alternative crowd, but we’re a tourist destination, a fashion destination and a destination for people who are looking for something different,” Maronde says. “We want to be a stronghold for creating a sense of community, which is why we have lots of gallery events and pop-up shops.”

Those special events, which often are staged in a partitioned area in the back of the shop, have included a collaboration with Corky’s Footwear that saw the space converted into a 1970s-style boutique and a pop-up shop by the Urban Cyclist at which customers could select each individual part they wanted for a custom bicycle. But the store wants to seem special every day, which helps explain the old airplane wings, scrounged from an airplane graveyard in Greeley, that serve as partitions in the store’s changing area.

This Buffalo Exchange is especially popular in the fall, when the 25 employees can barely keep up with the flood of people seeking Halloween costumes. In October, Buffalo Exchange staffers will often wear costumes, especially on Saturdays devoted to specific themes (a favorite last year was Wes Anderson movies). “Halloween is ridiculous,” says Maronde. “It’s all hands on deck. And throughout the entire store, it’s nonstop — we’re giving out candy, people are dressed up, and sometimes we have DJs playing. It’s kind of a party atmosphere, and there’s just really good energy involved.”

Part of the fun is seeing what customers come up with. One of Maronde’s favorite costume ideas came from two women who bought 1940s-style country dresses and said that they were going to smear dirt on them to become “Dust Bowl babies.”

“I loved how simple that idea was, while also being really creative,” Maronde says.

But while Maronde thinks that Buffalo Exchange has succeeded in becoming an epicenter for creativity and alternative culture, he laments what he calls the “homogenization of Broadway,” as some of the street’s edgier, independent businesses disappear. “We’re definitely seeing something detrimental happening to the gay community here,” he says. “It was disappointing seeing the Crypt close, because on Broadway, we want to keep individuality going strong. But I think we’re holding it down for those people here at Buffalo Exchange.... We’re trying to build a community, not just be a thrift store.” — Chris Walker

BackCountry

10420 BackCountry Drive, Highlands Ranch

As you drive farther south on Broadway, the street’s characteristically quirky string of dive bars, secondhand shops and auto garages gives way to Audi dealerships, pseudo-wood houses and neighborhoods with names like Mansion Pointe. This is it: You’ve reached the suburbs. Not the single-story, ’60s-style ranch-house suburbs that flank Broadway in Englewood and old Littleton, but the real suburbs of Denver: Highlands Ranch.

After Broadway crosses County Line Road and dives into Highlands Ranch, you might as well be in a different country, let alone a different city. After miles of unfalteringly straight asphalt, Broadway begins to weave left and right as studio-quality green lawns and tall, rustling trees roll up on either side. The downtown Denver skyline, the last marker of the old Broadway, is only a hazy, distant memory lingering in your rearview mirror.

And then, just like that, Broadway ends.

As you cross Wildcat Reserve Parkway, you suddenly round a corner and find yourself in front of a large, opulent-looking visitor center adjacent to a pristine pond, where a pastel polo shirt-wearing grandfather sits with his skater-clad grandson. Broadway has suddenly become BackCountry Drive, and this is the Discovery Center of the BackCountry community. Mansion Pointe, Shmansion Pointe; this is the zenith of Highlands Ranch suburbia. Inside the Discovery Center, shining oak walls are ornamented with serene, black-and-white nature photographs of exotic horses and river stones that unimaginatively mimic Ansel Adams. Also along the walls are informative facts about the land’s history (it was once almost the “center of the Arapahoe nation”) and fairy-tale phrases like “There is still a place where sunbeams trace the land…”

The gated community boasts hundreds of large luxury houses worth as much as two million dollars and designed to incorporate the surrounding natural scenery. After driving past these homes along winding streets like Wintersong Way and Timberdash Avenue, you eventually wind up in a stunning wilderness area acquired through a partnership with Douglas County. As the information guide in the Discovery Center proudly promises, this area is dedicated to “recreation purposes” and the protection and “enhancement” of open spaces.

The only catch is, the open spaces aren’t so open. The 467 acres of open space beyond BackCountry “have been set aside for exclusive, private use for BackCountry residents,” it turns out. For a non-resident to hike the community’s private trails, you must fill out a form at the Discovery Center that indicates which homes you might be interested in and when you would want to move in. “Yours alone,” the informational guide says.

Broadway has met its long, lonely end: “It’s serene to meander through this land, reconnecting with nature, without fully disconnecting from the world you left behind.” But the world of Broadway seems a million miles away.

Welcome to BackCountry land. — Gabe Fine

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]