Ex-members of the Colorado Green Party aren’t surprised that Mérida is delaying the democratic process. According to Gary Swing, who joined in the 1990s, the party’s last legitimate assembly was in 2016, before Mérida’s complete takeover.

The idea for an American Green Party emerged in 1984, inspired by green parties in other countries. Supporters held their third national gathering in Estes Park in 1990, creating an early stronghold in Colorado, where a local party was established in 1992. Just a few years later, Ralph Nader ran for president on the Green Party ticket, helping the party gain national attention, though the Green Party of the United States wasn't officially founded until 2001.

The Green Party is one of seven officially recognized parties in Colorado, including four other minor parties that gained automatic ballot access by either receiving 5 percent of the vote in a campaign for statewide office, having 1,000 registered voters or submitting a petition signed by 10,000 Colorado voters. After putting its first candidates on the statewide ballot in 1994, the Green Party has had that status since 1998.

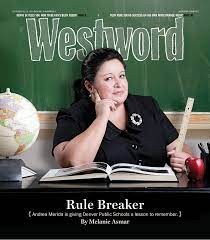

Mérida became a member just over a decade later, during her tenure as a member of the Denver Public Schools Board, thus becoming Denver's first elected official who was a member of the Green Party. Before that, she'd belonged to the Democratic Party, and even served as a precinct captain in House District 2 before deciding to take more direct political action by running for the school board as a Democrat.

She was a controversial figure on the board from the start, secretly swearing herself in so that she could vote on controversial reforms in November 2009. After that, Mérida faced a recall attempt for penning a disparaging op-ed about Michael Bennet, the former DPS chief who'd been appointed to the U.S. Senate by Governor Bill Ritter, while on the payroll of his 2010 Democratic opponent, Andrew Romanoff. She also overspent her expense account by more than $8,000, initially refusing to pay any of it back. On top of those infractions, she didn't work well with others, according to fellow boardmembers.

Mérida announced in 2013 that she wouldn’t run for a second term. Today she says serving on the school board is what chased her away from the Democratic Party. “They weighted teachers' pensions and put them in pay swaps, they pushed the charter school agenda and union-busting,” she remarks. “Unions, public education and preservation of pensions used to be Democratic ideals, and they no longer were.”

Swing remembers when Mérida joined the Denver chapter of the Green Party. He voted for her when she ran to be an officer in 2013; he says he was excited that someone with experience as an elected official wanted to help out. But then Swing learned about her history on the school board.

In 2017, Mérida ran to be a co-chair of the state party. At the time, party policy held that there had to be one man and one woman serving as co-chairs; she and Harry Hempy, a Boulder-based Green Party member, initially agreed to run together.

But Hempy says that he and Mérida had a disagreement about when the Green Party's state assembly should be held, with Hempy wanting to hold it in March or April to maximize the time the party would have to prepare for the 2018 elections and Mérida preferring August, because she had been installed as co-chair in August 2015 and thought she should have a full two-year term. Mérida switched to supporting incumbent state co-chair Bill Bartlett, and she and Bartlett ended up as state co-chairs since no other woman ran.

That wasn't the only controversy that year. According to Swing, the assembly was held in Denver for the second consecutive year, despite a tradition of it moving from city to city to include other areas of the state; Grand Junction had already been proposed as a site.

Swing, Hempy and other former Green Party of Colorado members say that Mérida stacked that assembly with people she’d recruited as temporary Greens who hadn’t been part of the party before. Mérida used those people as a way to out-vote other groups, presenting a different agenda than the one that had been previously agreed upon, they say.

The new agenda didn’t allow discussion of changes to the party bylaws that Mérida had proposed, review of state office-holder’s actions throughout the year, or public disclosure of the treasurer’s report. It also called for those running for office to only have ninety seconds to speak. Swing asked for five minutes for each candidate and was denied, he recalls.

Hempy says he volunteered to be treasurer and was the only one who stepped up, but the position was never voted upon. To his knowledge, the party hasn’t presented a treasurer’s report to membership since then.

The agenda also called for giving the state council expanded power to kick people out of the party without a vote of members, Hempy says, adding that Mérida soon used that power to kick him out.

Mérida declines to discuss specifics of many of these allegations, calling them ancient history.

“There are interpersonal issues and ideological differences in every party, and it seems pointless to me to talk about those things,” she says. “I just find it very telling that we, as a nation, could potentially be going into war with Russia over the Ukraine situation; we have climate change due to the fact that we don’t have sensible energy policy; here in Colorado, we have a governor who supports the fracking industry — and this is what gets picked up.”

But the other past and present Green Party members with whom Westword spoke say that while they were previously hesitant to expose problems within the party, they finally decided it was important to do so because it appeared that, once again, the party might not hold an assembly within the bounds of state law.

Along with Bartlett, Hempy and Swing, nearly a dozen other former Green Party members have been kicked out of the party by Mérida; each had run for office or held one within the Green Party. They say that kicking them out allowed Mérida to consolidate power for herself.\

Susan Hall, the 2012 Green Party nominee for Congress in District 2, was a delegate to the national Green Party in 2018 when Mérida was an alternate delegate; by kicking her out of the party, Mérida gained more power by becoming a delegate, Swing says.

Local chapters including the Jefferson County Green Party, the Douglas County Green Party, the Greater Boulder Green Party, the Pikes Peak Green Party and Southwest Greens were also removed from good standing by Mérida, cutting the number of local chapters nearly in half. There are currently six recognized local chapters.

“The idea of being a member in good standing has been totally abused,” Swing says. In the past, all it took was being a registered Green Party voter and a member of a local chapter. Now it also means complying with what the state party sees as proper behavior. “Over the years, there were various attempts to ban people from participating in the state party, but no one had ever actually been banned from the state party effectively until 2017,” he adds.

While Mérida says she operated fairly and used due process when kicking people out, exiled members point out that most of those decisions happened on a closed online forum where they weren’t allowed to post without their comments being approved by Mérida. The party has historically operated through an online forum where all resolutions were introduced, discussed and decided upon, allowing collaboration between party members without a physical meeting. Once Mérida became a moderator, members say, the previously open discussion stopped.

People who are banned can't participate in any state party function, including holding state party office, speaking at an annual meeting or reading the forum. They can still register as Green Party voters.

In response to Mérida’s actions, several banned members, including Hempy, filed an official grievance with the National Green Party’s Accreditation Committee in 2017, describing Mérida’s antagonistic activities and outlining times that she’d broken party bylaws. It took the national committee over a year and a half to rule on the complaint; in that time, the committee grew from eight members to 49, which banned members say stacked it against them. The committee ultimately ruled in Mérida’s favor after she refused mediation with those who filed the grievance.

The national party declined to comment on the controversy surrounding the Green Party of Colorado.

After the national party ruled against the banned members, Swing submitted a complaint about Mérida’s conduct to the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office in 2019. He wrote that Mérida restricted voting rights by instituting a dues system for those who wanted to remain in good standing, which she denies, and violated various other state bylaws.

The office responded by saying it does not have authority over internal party conduct and that the only way to challenge party actions would be in court. The secretary of state's office did not respond to a request for comment on the Green Party's current status.

Mérida says that the people were kicked out not because of her personal feelings, but because they opposed the party’s new bylaws, which she describes as anti-oppression. “One of the things I’ve noticed across the party is that the quickest way to halt collaboration is to allow a serial abuser to stay in your midst,” she says. “If someone has the inability to operate in a peaceful, collaborative and respectful manner, then what ends up happening is that good activists go away. We decided we would rather have a collaborative environment than having to constantly entertain chaos or disrespect.”

Some of the more vocal advocates against her are white men, she notes. However, women and people of color have also taken issue with Mérida’s actions, including Charmaine Barros and Dawn Neptune Adams, Indigenous women who filed a grievance against Mérida after they traveled to Standing Rock to join the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“We feel that [Mérida’s] actions at Standing Rock violated Green values of respect and fairness, especially toward members of oppressed communities,” their complaint states, before describing how Mérida took over the expedition, ignoring their desire to bond with other Indigenous people by making them camp away from the rest of the protesters, refusing to stand during Indigenous ceremonies and sneaking to the casino during the day.

Nothing came of the complaint, which Mérida says was completely fabricated. Neither Barros nor Adams responded to a request for comment.

Bob Kinsey, who lives in Colorado Springs, ran the Pikes Peak Green Party from 2011 until it was removed from good standing in 2017. Kinsey was a candidate for Congress in District 4 in 2004 and a Senate candidate in 2008 and 2010 before moving to the Springs, where he ran for city council in 2012. He says the chapter was removed for missing two votes on the steering committee, a rule that was never enforced before Mérida took over.

Kinsey doesn’t think kicking people out over minutiae is beneficial to the party overall. He stopped associating with the state party after the 2017 assembly, though he’s still tried to help the exiled Pikes Peak chapter survive. He has a bumpersticker urging people to register with the Green Party. “It sends a message to the other parties that there are significant numbers of people in Colorado who find the two corporate parties to be playing the wrong game, particularly when it comes to environmental issues,” he says.

Mérida characterizes her detractors as being interested in chaos rather than advancing progressive policies, describing them as “idiosyncratic outsiders” — despite the fact that most of them were part of the Green Party before she was.

Swing worked with some of the first Green Party candidates to make the ballot in Colorado in the 1990s, while Hempy, like Mérida, left the Democratic Party in 2013. “I felt they paid way too much attention about how much money a potential candidate could raise as opposed to their positions on issues,” he says.

But Hempy thinks that under Mérida’s leadership, the party has departed from the positions that drew him to it in the first place. Its stated value s call for ecological wisdom, grassroots democracy, community-based economics and economic justice; social justice and equal opportunity; nonviolence; decentralization; respect for diversity; feminism and gender equality; personal and global responsibility; and future focus and sustainability. “These are just empty words to the people who run the Green Party today,” Swing says.

Since 1994, the Green Party had run candidates in every general election. The first time that the Colorado Green Party failed to nominate any candidates for statewide or congressional offices was 2018; none ran in 2020, either. This year, Mérida says that the party isn’t focused on nominating candidates, but instead on building a grassroots movement that would create more support when candidates do run.

“I don’t know that the party ever has run a full slate of candidates, and what you want to make sure that you do is have a local nucleus of people that can support candidates,” Mérida says. “What has happened in the past is that people have just decided to run for office and we just can’t do that.”

The Libertarian Party, another minor party with automatic ballot access in the state, says that it always aims for a full slate of candidates.

Almost every member of the Green Party who worked the People's Fair in 2015 are now banned.

Gary Swing

But Kinsey also says he understands why some potential Green Party candidates are turned off by the current situation.

“The toxic experiences that many of us had…were traumatizing,” agrees Swing. “That has caused a lot of stress and anxiety, and people drifted away.”

While many banned members say they've been completely turned off from electoral politics, others have considered forming a new party that fits the original Green Party values of ecology and pacifism. One of those hopefuls is Hempy, though he thinks the prospect may be too difficult. Although his three-year ban was up in 2020, he hasn't attempted to formally rejoin the party, and instead is considering his options.

“The two-party system is a football game,” he says. “It's like a winner-take-all, and the main reason I joined the Green Party in the first place was to help create a multi party system of government. ... Fighting battles with corrupt Andrea Mérida is just too hard for me.”

The Green Party once had a motto: “Two Greens, two opinions or, better yet, two Greens, three opinions.” Under Mérida, Swing says that Colorado's Green Party should now be using this slogan: “All Greens, one opinion.”