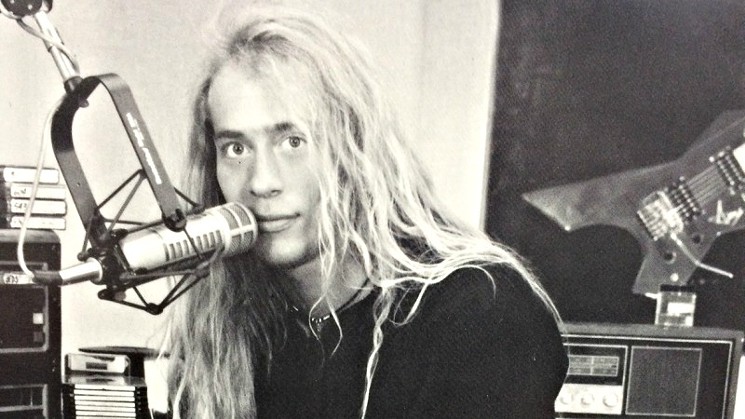

The man born Stephen Meade and originally known as Willie B. Hung has gone from being a graveyard-shift wildman to anchoring KBPI's ultra-popular morning-drive show and serving as the outlet's program director. And instead of making the kind of headlines that nearly got him fired, as was the case with the so-called mud fest controversy in 2000, he's pouring his energies into what promises to be the biggest charity project of his career: obtaining, restoring and giving away 100 cars to needy families during the 2018 holiday season.

During the following conversation, Willie talks about his Deep South boyhood and early decision to become a DJ ("Weird Al" Yankovic played an unexpected role); the day he fell in love with Denver and the circuitous route that brought him to the Mile High City; early battles with management over music he saw as stodgy and behind the times; the bet he placed on himself that led to his move to mornings; the muddy mess that nearly cost his career and how he got out of it; and his devotion to what he refers to early and often as "the BPI Family."

In addition, Willie offers new details about KBPI's recent signal shift from 106.7 FM, where it had been for more than two decades, to 107.9 in order to accommodate a new country station, The Bull. Turns out the transition was more difficult than anyone imagined thanks to a series of technical challenges that are closer to being resolved now than they were at the time of our original chat, which took place on March 13, shortly before iHeartMedia, KBPI's owner, declared bankruptcy. According to Willie, the quality of the signal on the east and southeast sides of the metro area is much improved, and engineers are hard at work boosting it for listeners in and around Boulder. Before long, he's confident that all of metro Denver will be rocking as hard as ever.

Just like Willie B himself.

Westword: Where are you from originally?

Willie B: Originally I'm from a small town called Winchester, Kentucky.

How long did you live there?

Until I was nineteen.

How would you describe the town and your family?

I grew up in a fairly large family. I had my twin brother and an older sister, but the family has a lot of roots. On my dad's side of the family, he had a couple of sisters, and I have lots of cousins. And we lived on an 850-acre dairy farm. I grew up on the farm, milking cows and doing all that shit. On my mom's side of the family, it was an eastern Kentucky, Appalachia little country-store scenario. So it was a very weird, middle America, rough, hard-work type of thing when I was a kid. My rite of passage was — people would call it a machete now, and we'd use it to clear tobacco on a ten-acre plot. You've got your own little carved-up machete with your name on it and you've got to go to work on the farm. It's kind of weird thinking about that as where I grew up and where my original roots are at, being here now.

When did you first get into music? What's the first stuff you remember really connecting with?

It's funny. I like all types of music. When I was growing up, one of my best friends was this black guy named Bubba Gatewood, and me and him would breakdance. I went from breakdancing with that kid to everything else. My town, being a very, very small town, didn't have a true rock station. So our version of rock in my home town would be like Grateful Dead and the Beatles and so forth. But I got into radio really early. I knew in fifth grade I wanted to be a radio DJ because this dude wouldn't play my song.

Do you remember which song?

Oh yeah. Dude, are you ready for this? It was "Weird Al" Yankovic, "Another One Rides the Bus." No kidding. I was in fourth grade, and back then, if you recall, you used to be able to hit the play-record button on your cassette player and it would record the song, and you would have it taped. That was our version of downloading. So I was waiting for this song to come on after I called to request it, and when it didn't play, I called this dude again, and he finally lost his temper. He was like, "You dumbass. When I said to call back later, I didn't mean call again in twenty minutes. If you want to hear your song, get your own radio show. Go get your own radio station." He was, like, dogging me really bad. And so I was kind of hurt by that. The next morning, I walked up and told my mom, "I want to be a radio DJ." She was like, "What?" And I said, "That's what I want to do." And literally that phone call changed the direction of my life.

That desire to become a radio DJ was still going when I was in seventh grade and our teacher said, "Go to the card catalogue and pick out something you want to be when you grow up." I was looking under "D" for "DJ." She told me to look for a real job. And when I got on the radio and started doing weekends, she was the first person I ever put on the air.

You called her up and put her on the air?

Oh, yeah. My mom's a teacher, so we were all friendly, so the first time I was on the air, I called her up and went, "Guess what I'm doing? Remember you told me to get a real job?" It was funny. My very first phone call on the air was kind of rebellious — like "Nyaa, nyaa, did it," you know?

Did you do any radio in high school? Or was this a job at a commercial station?

There was a radio station called WFMI. It was an FM station, and we used to call it a border blaster, because it sat on the Clark County line. Literally about ten feet off the county line, and it aimed toward Lexington, which was a big, monster city in my eyes. I wanted to be on WFMI, but my stupid Kentucky Southern drawl was so bad that the program director wouldn't put me on. He put me on WHRS-AM, which stood for "Horse Radio," and I did things like the tobacco report.

So you weren't playing music at first?

It was an easy-listening station, and it had big pancakes of tape. You'd stop the tape machine, you'd flip a toggle, turn a big knob, read the tobacco report or some liner card, and then you'd turn the mic off, turn the toggle down, reach up and hit "play," and this big pancake would go. Then, every hour or so, you'd switch the reel-to-reels. We had, like, fifty of them. It'd be, "Here goes this reel."

The funny thing was, I got on overnights, but I also used to run Casey Kasem's Top 40 countdown on WFMI; I would call my friend and tell him to wake up at 6 a.m. on Sunday and have him do the weather report. I did that for a long time, and I was finishing up one Friday night on WHRS, and the overnight guy was too drunk to come into work. My boss called and said, "Do you know how to run the board on the FM?" I said, "Yeah, I run Casey Kasem's Top 40 countdown on Sundays." He's like, "Go on. Just play music. Don't talk and cover his shift." I did that, and by, like, the third song, I was on — started shooting the shit, taking phone calls.

My boss knew right away. He said I sounded stupid because of my accent, and if I got that right, I could come on and do a couple of shows. So I went to speech therapy and had them help me with my accent.

How strong was your accent? If you were talking the way now that you did back then, would people from Colorado even be able to understand you?

They would be able to understand me, but you have to understand that at the time, I had a big, enormous Southern drawl. I have my mom on the radio, making football picks every season, and everybody thinks it's a riot, because my mom has such a strong Southern drawl, too. Her dipthongs are all weird. And that's my mom, who lives in Florida and has been out of Kentucky for a decade and a half, two decades. But you get my aunt on the phone and then you really hear how deep my family's Southern drawl is. My aunt and the rest of my family in Kentucky have a severe Southern drawl. When you hear them talk and the way they say certain things and words and describe things, it's hysterical to hear, because it's so out of place. But there it just seems natural.

After the speech therapy, did your boss keep his word?

Yeah. They finally put me on the FM side, and I took off from there. By the time I was a senior in high school, or just getting out of high school, I became the seven-to-midnight jock on our little hometown radio station. Then I got a job offer in Charlotte when I was nineteen. Took the job, moved there, and helped put a couple of radio stations on. That's when I kind of discovered the rock thing.

What was some of the first rock music you got into?

Back in the day, it was weird. I started leaning toward a lot of the grunge stuff, but also a lot of the industrial stuff — early Front 242. And Ministry. Dude, Psalm 69: That CD changed my life. I remember listening to that, and at the time, I was working at a station that played a lot of mainstream rock — and in 1989 and 1990, what was mainstream rock? It was Poison, "Every Rose Has Its Thorn." So when you hear something like Ministry's "Jesus Built My Hotrod," it's so distinctively different and so much more aggressive. It changes the whole aspect of how you ingest hair bands or Poison songs.

In a weird way, that Charlotte station led to the connection that took me to Denver. I used a guy named Randy Michaels as a consultant for my show and for my station in Charlotte. It did really well. Then the operations manager got a job in Florida, and he hired me to do the same thing I did with the station in Charlotte — taking it alternative, kind of industrial, and doing some cool stuff on it. I went down to Orlando, did that for a while, but it didn't go the way I thought it would. My purpose to move to Orlando was to flip that station — it was called WVRI, which stood for Variety 101 — and make it rock that leaned alternative. So I pulled all the rules on our music-scheduling system and told the owner, "This is going to get your cume to pop, but in reality, we'll fade. Then we'll hit the format change." But when the cume popped, he didn't want to change formats, and I was like, I'm not staying at more of an adult-contemporary kind of station. And the ironic thing was, just like I predicted, WVRI faded, and it ended up switching a year later to WJRR, which became a pretty legendary rock station in Orlando.

Anyway, I didn't want to stay in that format, so I called my consultant, Randy Michaels, who was working his way up the ranks at Jacor [a company that was a precursor to Clear Channel and, later, iHeartMedia].

Randy Michaels became a big deal.

Yeah. When I used him in Charlotte, he was just a consultant, but he started dabbling in programming and was helping some stations — and he really took off after that. When the Orlando thing fell through, I called him, and he got me a job in Tampa behind Bubba the Love Sponge. I worked there for a few months, and then I started getting some other job offers. I was offered a job in Phoenix, and I was in the running for jobs in some other places that were decent. But where I really wanted to go was Denver.

I came out here, got a room at the Quality Inn off of Hampden, then got in a rental car and drove up 285. I thought, I'll just drive west, and I got up in the mountains and it was snowing and the flakes were, like, two inches. They were huge. My car was covered. I turned around after I got to Bailey and drove downtown, and it was just amazing: It was like sixty degrees and people were running around in T-shirts and shorts. I was like, this is the craziest place I've ever seen in my life. I've got to be here. It was the first place that ever felt like home. So I told Randy, if you ever get something in Denver, let me know. He hit me up when I was in Tampa and said, "We've got a job at a rock station in Denver. It's a bottom-of-the-barrel job and it's a pay cut. Do you want it?" And I said, "Hell, yeah." I moved out here, bro, in a pickup truck with a suitcase, a house plant, two cats and a toolbox.

When you got to Denver, how old were you?

I was 23 or 24.

So in your early twenties, you were already flipping stations? That seems really young for you to be doing that. But did it feel natural to you?

At the time, it was looked at as young, but it just seemed natural, because that's what was happening. That was the era when grunge was just getting going. You could tell there was something different and aggressive. There was something in the swell of the kids and the youth. I remember coming to town and telling you there were forty-year-old dudes who weren't into the lifestyle programming music for 18- to 34-year-olds! [Willie B. told me this for a music column that predates Westword's Internet archives.]

After that article ran, I got called into [then-KBPI overseer] Jack Evans's office. He read what I said in Westword and asked, "Do you really feel that way?" And I said, "The reality is, that's the truth. I know you're here to give me shit, but that's the truth. You don't understand it." That was always my sort of battle with those guys.

I think one of the bands we first talked about was Nine Inch Nails. When I first came here, these guys had no Nine Inch Nails tracks in their library, and I was like, "If you're not playing four or five songs off Pretty Hate Machine, you're an idiot." They just didn't get it. But at the time, that was one of the cool things I could bring to the table that these guys were completely oblivious to.

How did you break down the barriers and get them to let you put more edge into the music you were playing?

Honestly, dude, I just played it — and I was fortunate, because I had free rein. When I got hired to do nights, it was one of those things where they basically said, "Willie, we're not sure what we're going to do with this format, how we're going to make this work in Denver." It was just literally, "Just get us some ratings."

There's a phrase that goes, "It's better to apologize afterward rather than ask for permission." Was it that kind of situation?

Yeah, and it is even now. I've been playing Jacob Cade, who's not on our playlist. He's this kid out of Parker, Colorado, and he's a riot. He's badass. Kid's got crazy energy. When I find something like that now, it's much different. But in the early years, I'd find something like that and play it, and it'd come with a lot of pushback from the people that were kind of controlling the station at the time. It came with a lot of, "Why are you doing that? It's not tested. It's not proven" by all those filters and the litmus tests that people gather. At the time, the people who were programming our music were doing all this testing — like, "We need to put in five songs from this category and five songs from that category, and have them rotate 50 percent. One category rotates this hour and the other category rotates that hour." It was really formulaic. Just a homogenized, cookie-cutter formula that they used in a lot of stations at the time. It was probably pulled from Top 40 stations, the way their rotations were, and they'd put them in rock. We just changed that whole thing, which in this town I thought was really needed.

How did you transition from late nights to the morning shift?

I went to my boss in 1999, when my ratings at night were very good. I was pulling really big numbers in the old diary methodology, because I was always trying to push the limits and have fun, but I was coming up on the end of my contract. So I told the boss, "I'll work free for a year and do both mornings and nights." At the time I was getting paid a decent amount for nights, but that was really all you could make in the country being a night jock at a radio station. So I said, "I'll work free for a year. I'll do mornings and nights. And you don't have to give me a dime extra. But if I get the morning show into the top five, I want to be paid morning-show salary. If I don't, I'll go back to doing nights and you got extra work for free and funny shit on your morning show for a year." And he said, "I'll write that up."

He totally wrote up a contract. So I'd come in to do the morning show, and after that, I'd go to the gym about three miles away. I'd shower there, do my music-director stuff, and I'd go on again at night. Literally the radio station was all I did for a year. And the morning show went from fourteenth to seventh to fourth to first. When I got first, I walked in, gave the boss the report and was like, "All right, now I get a morning-show contract and I don't have to do nights." So that's what got me off nights.

Around that time, you were getting more popular, but you were also sometimes making headlines and stirring up controversy.

In the two-year span leading up to that, I had two incidents. Everybody knows about the chicken thing. [In February 2000, he faced an animal-cruelty charge after he directed an intern to heave a live chicken out a three-story window.] And then there was the mud fest, and what I learned from that was, regardless of how some people are and whether or not you judge or view them as being up-front and honest, they'll always try to screw you.

Case in point: I was up four-wheeling a week or two before that whole mud fest thing happened, and I was wheeling in a spot that had a few other guys in it. One of the guys was stuck. We got him unstuck, I helped out, and he said, "Hey, we're heading up to Nederland to go mudding. Do you want to go with us?" And I was like, "Hell, yeah." I drove up to Nederland, and there were probably six or seven people mudding that day in this one spot. I tried it, got stuck, got unstuck, and the next Monday, I came back on the air and started talking about it. I said, "Dude, this place is hilarious. Saw some friends up there, met some people. Hey, if you guys want to go up there, let's meet up at the Costco just outside Boulder and let's go up there, see who can get through it."

There ended up being about 600 trucks. I was like, "Holy shit." I remember going up the service road — I put my rig on my tow truck — and before I could see the Costco, I could see people parked along the service road, and everything looked like big trucks. I was like, "No, they can't be here for what we're doing." But the Costco parking lot was fucking full. I was like, "Holy shit."

I had no idea it was a private property or any of that. There was a No Trespassing sign, but it was down, and even though you got to it on a forest road, the mud pit was private property, because the owner had been grandfathered in.

I know there was reporting at the time that it was a nature preserve or something like that.

Even though there were no records of an arboreal toad in that part of the country, they deemed it a good habitat if indeed there were arboreal toads there — although nobody's ever found them. So I learned my lesson there.

A lot of people showed up, and we tried to be as organized as possible, but it became a big deal, even though the fine wasn't that big. Because the No Trespassing signs weren't up, the judge in Boulder gave us a fine of $75 for assembling more than 75 people in one spot without a permit. That's all we got from the judge. That was our punishment from Boulder. But we had to settle with the guy who owned it, and I think we settled for $42,000 to reclaim the land. We had pictures of it from before, and people had wheeled in it before we showed up — and when I went up there again a year and a half later, the guy hadn't changed a single thing. But it is what it is. That's the way it works.

Did the bosses at the station look at what happened as almost a positive thing, since you got so much attention? Or was it bad all the way through?

They treated me like it was a bad thing. I almost got fired for it. But I went to the boss and said, "We can pay for this. Let me do this CD. I'll sell 10,000 of them out of the trunks of our cars at remotes and appearances and we'll raise the money." So they gave me a couple of months and fronted me something like $4,000, and we did this CD. We called it The DUM CD, which was "mud" spelled backwards, and the picture on it was an aerial shot of the dude's place with people mudding in it a year and a half before we were there. Just a little sarcastic jab. And we ended up paying for the whole thing.

They were pretty cool in letting me do that, and I think the only reason they did was because I hadn't let them down yet. I was like, "Let me make this right," and I'm always trying to do that. I'm always trying to make things right, and that was one of those moments: "I'll raise this money and make it right and it won't happen again." So it was both good and bad.

You mentioned that you'd become music director. How did that happen — and when did you move on to higher management?

We had this guy, Mike O'Connor, who was awesome and insane at the same time. A lot of radio people have that combination, I believe. Mike was like, "Here's the deal. Everybody under my tenure starts with a clean slate. You get a chance to prove yourself. If you bring more economic value to the table, then you'll be rewarded with being able to move up." And he gave a bunch of us the chance to be music director. All we had to do was pick songs, and we were graded by how the songs ranked in the country in active rock. Whoever picked the most songs that ranked high after six months won the music-director position.

Fortunately for me, I beat everybody out and got the music-director position, and that came with the title of assistant program director. Then Mike O'Connor said, "You're going to have to earn the program-director title within the next twelve months." So I had to do a bunch of challenges to prove what I could do behind the scenes — figuring out rotations and categories and how to align things with demographics and things they were passionate about. But what really did it was this event — a car show.

For a number of years, nobody had given me a chance to do a car show. I kept going to my boss, and he kept saying nobody would show up. So I just did one myself so I could give my buddies some trophies, and the couple of years I did it myself, it got so big that it wouldn't fit in the parking lot I was holding it in. So I went to Mike O'Connor when he became the boss and said, "Will you give me a chance to prove this will work? Here's the budget I need, and I think I can raise this money. And here's what I think we'll get out of it." He gave me that opportunity, and the first time we did it, 384 cars showed up. Mike O'Connor drove by the car show, which was at Southwest Plaza, and he couldn't believe what he was seeing. After that, he put an email out saying I was the program director. That's how that kind of fell into place.

You're just about to celebrate your 25th anniversary at KBPI. Given all the changes the radio business has gone through, it's amazing that you've been there for so long. Is that something you ever would have thought possible?

No. But even now, I love coming to work — and that's why I started the whole BPI Family thing. I started it years ago because I really do look at them as family. It sounds stupid to say, because it's cliché as shit in most of its applications — and in reality, most people are about dollars. But I got a big shop behind my house, and there's a revolving BPI Family car behind my house basically eleven months of the year. I just fixed the car of this one girl, Tasha. Just had another girl, Linda, who's 62 and was cancer-free for four years. But then in November, the cancer came back — and her car's clutch was going out. So I helped get that fixed. It's just one of those things where I look out for listeners, and it's been super-rewarding.

I think in the first years of my career, me doing that probably caused some friction with management, because it wasn't how they did things or the lens they looked through. This sounds bad, and I don't mean it that way, but it was about the dollar for them. And I've turned down endorsement deals for companies that would rape BPI listeners on interest rates. Like, "Fuck you. You charge 21 or 23 percent. I'm not endorsing you." It may be a $100,000 client, but I've told my bosses, "I'm not endorsing that guy" — and initially that caused a lot of friction, too. But now it's beneficial, because they know I vet the people I endorse. That's the reason it works, because my listeners know that.

Right now, the action-rock format isn't doing well around the country, but it's doing well here. Do you think it continues to succeed in Denver because of something about the city or because of your listeners' connection to the station?

I think it's a little bit of both. This market has had a real history, a real lineage. There have been a lot of rock signals in this market for years. Denver has always been a rock town, which is one of the reasons. They just have it in their veins, in their DNA, if you're from this market, if you're from Colorado. But I think a lot of it is because of the connections we have with our listeners. We do a lot of things that connect to what they're passionate about in their lives, whether it's the car thing or the Broncos or doing fun shit with them or charity cruises or rides or that type of stuff. We do a lot of stuff that engages our listeners that a lot of people don't do anymore.

This church in Beaumont, Texas, was filled with donations from BPI Family members after Hurricane Harvey struck last year.

Courtesy of Willie B

I think so. I do a downtown takeover cruise, and this year, there were about 1,700 cars that filled up theElitch's and Pepsi Center's parking lot. For about two hours, we consumed downtown, and, dude, it was a lawless-ass time, too. It's burnouts and mayhem and fun, but in a controlled-chaos scenario. And being able to activate your audience about stuff they're passionate about has been a big-time BPI asset for a long time. Even now, in a world where your phone is delivering as much content as you can ingest, there's still a great use for radio. How people consume radio is changing, but to me, I think it's working fairly well. I don't have a radio in my house now, but I have a smart speaker, and the smart speaker is the alarm clock. So we now have radios going back in the homes because of the smart speakers, as weird as it seems. And that's kind of cool.

What were your thoughts about the signal change? Was it rough for a while, or did it go smoothly?

Hell, no, it didn't go smoothly. I got brought into a meeting in late November, early December. As soon as I walked in, there was my operations manager and my program-manager guy — the guy who's in charge of all the content on the FM. I was like, "Huh?" And they were like, "We've got to talk to you." I had the feeling I was either going to get fired or it was going to be a signal conversation. There's been a rumor going around for years that they were looking to put a country station on in this market, and the format they basically wanted to make country was KBPI — but KBPI made a lot of money for the company. So it was always a big question mark. Do we blow up a station that makes $6 million for a station that might make $9 million? That was a hypothetical, but in reality, I'm sure that's how they looked at it.

So they called me in and said, "We're going to commandeer your signal. We're going to take over 106.7 and we're going to put country on it." And dude, at that point, my heart hit a bottom that it hadn't hit since my first wife left. At first, I was like, "The fuck you guys are." They said, "We're going to put your signal on and we're going to do it in Fort Collins and we're going to aim toward Denver and try to hit the market that way." And I was like, "Not a fucking chance. You might as well put me on the afternoon show of the country station if you want me in this building, because you're punching our death certificate." They said, "Your listeners care enough about you and they care enough about the format — and you're the only guy who can make the move and carry his listeners." And I said, "I'm not fucking doing that move. You guys give me a couple of days to think about it and figure something out."

I went home and started looking up FCC.gov. You can find maps of frequencies on there — how they hit different markets and things like that. Then I came back two days later and said, "Hey, there's no way I'm going to take that deal if that's all there is. If you guys are taking my 106.7 frequency, I want Colorado Springs and I want translator links to fill in the gaps." And so we went round. They were like, "There's no way that's happening." But about a week and a half later and after about 900 emails, they blew up the Colorado Springs station, which was probably, like, a $2 million station, or somewhere in that ballpark — it was Z-107.9. That way, we could have a common signal up and down the Front Range, and our engineer and the team mapped out coverage via translator links in the metro area and what it would take to phase them and so forth. At the time, when the team looked at it and assessed it, they said, "You're going to get 85-95 percent coverage in the metro from your old signal." And I was like, "Dude, I'll take that."

The reality was much different from that. They fired up the translator link, but I think because of where they put it, which is on a building downtown, we didn't get anywhere near that percentage. Basically we have our signal from the north and it gets boosted downtown, and we have our signal from the south, which fades out in the Castle Rock area. And we had a gap there.

My thing is, "You promised me this. Show me you're continually working on it until we get to the point we need." Because I'm a huge believer in standing up for your word. If you say you're going to do something, you're breaking your back until it's done. I even told my listeners, "I will stay on them every day until it's right." And I did. I even talked to Bob Pittman.

He's the CEO of iHeartMedia, right?

You've got to understand, dude. If you go high enough on the food chain, there's one guy — there's always one guy. Bob Pittman is that guy — and he was coming to town. He talked at this big meeting with all these iHeart people, and when I raised my hand, the whole fucking crowd went, "Oh, shit." But I asked him about something totally irrelevant, because I knew I would have time with him later.

After that, he sat down with me and a few of us jocks and started giving us a speech about how important loyalty and brand is — and I figured that was the best time to get answers. I said, "I've got a great brand that has a super-loyal base, and we just got bludgeoned. The signal went country, and I was promised coverage in the metro area, but it's been shit. What are you going to do to help us?" He started saying, "We're looking into certain translator links," and I was like, "No, no, no, no, no." He looked at me, eyebrows raised. And I said, "I've heard all kinds of words about translator links, and in my mind right now, it's all lip service. What I need you to do is to look into my eyes, the president of my company, and tell me you're going to fix this." And he did! He's a guy I'd never seen except on video, talking numbers I don't care about. But what he did was really cool. I never thought the president of my company would be like that.

What's happening now?

There are other translator links we have in our building that run other signals in the metro that are much stronger than the ones that 107.9 is currently on. I had to enlist the help of our parent companies and a bunch of technical gurus to basically un-code the FM signal from the simulcast of what it was carrying so we could see in a ratings scenario what the translator link was doing to this particular signal. If it doesn't boost the signal's ratings significantly, I'm taking over that translator link, which has really great coverage throughout the metro area. That's what we're in the process of doing now. It takes thirty days to acquire that data and compare the numbers in totality.

So the bottom line is, around the time of your anniversary, you're probably going to be able to deliver what's been promised all along, which is being able to drive from Cheyenne to Pueblo and hear the station without changing the channel?

Yeah. There are people listening to us in Trinidad, which is crazy. So the bookends are impressive. My job is to fix everything in the middle. I love that we're out there, but I just have to get this company to fix the supporting cast in the middle that ties it all together. And when it's fixed, it'll be great.

I've found out through the experience of not getting what you want that, in my world I've been blessed. I think Pablo Picasso said, "The meaning of life is to find your gift and then give it away." And my gift has been being blessed by the BPI Family and everything they've allowed me to get away with, and all the laughter they've put in my life....

I do this Cars for Christmas program where I give away cars. This past Christmas, I gave away 25 cars to needy families. I do it every year. The year before, I gave away nineteen cars. I've been doing it for fourteen years. And this year, I'm going to try to give away 100 cars. I'm working with a couple of dealerships to get wholesale cars. I'm working to get a 501(c)3, and I'm working with a couple of my friends in shops to do a huge, communal effort to try to give away a hundred cars. I've already got eleven that I've bought for a few hundred bucks and I fix up. So I'm going to try to give 100 needy families cars for Christmas. But they're going to give me as much as I give them.