See also: - Bye-Bye Brakhage - Stan Brakhage's film legacy lingers in Colorado - Alex Cox, director of Repo Man, joins CU-Boulder's film studies faculty this fall- From the Archives: Experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage rants about bad art

AMERICAN FALLS (OPENING SECTION) - DV, stereo from Phil Solomon on Vimeo.

Founded in 2005 by corporate philanthropic powerhouses that included the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Prudential Foundation and Rasmuson Foundation, United States Artists has since invested over $20 million in 500 of the nation's most creative individuals. An integral part of USA's modus operandi includes handing out fifty $50,000 fellowship grants to artists across the country each year.Earlier this month Solomon was in Los Angeles, where he attended a gathering for newly crowned USA fellows. Other members of the 2012 class include Keith Hennessy, a pioneer in gay and AIDS-themed expressionist dance; Nicholas Galanin, a Native American artist who specializes in multimedia; and Adrienne Kennedy, an African American playwright with an appetite for surrealism.

Solomon says the USA fellowships and other grants "make it possible to make the world a better place, even if it's just in small doses." But more than the money, he's proud of being included in such an eclectic, talented lineup. To Solomon, becoming a USA fellow was about being recognized as an artist -- not just a filmmaker. And it's this distinction that reminds him so much of his former adviser and best friend: Colorado film-making legend Stan Brakhage.

"He would have loved this, that I got this award," Solomon says. "This was an artist award. I got this along with painters and poets and dancers and writers. It's really extraordinary, the diversity not only of cultures but artists, too. These are my kind of people."

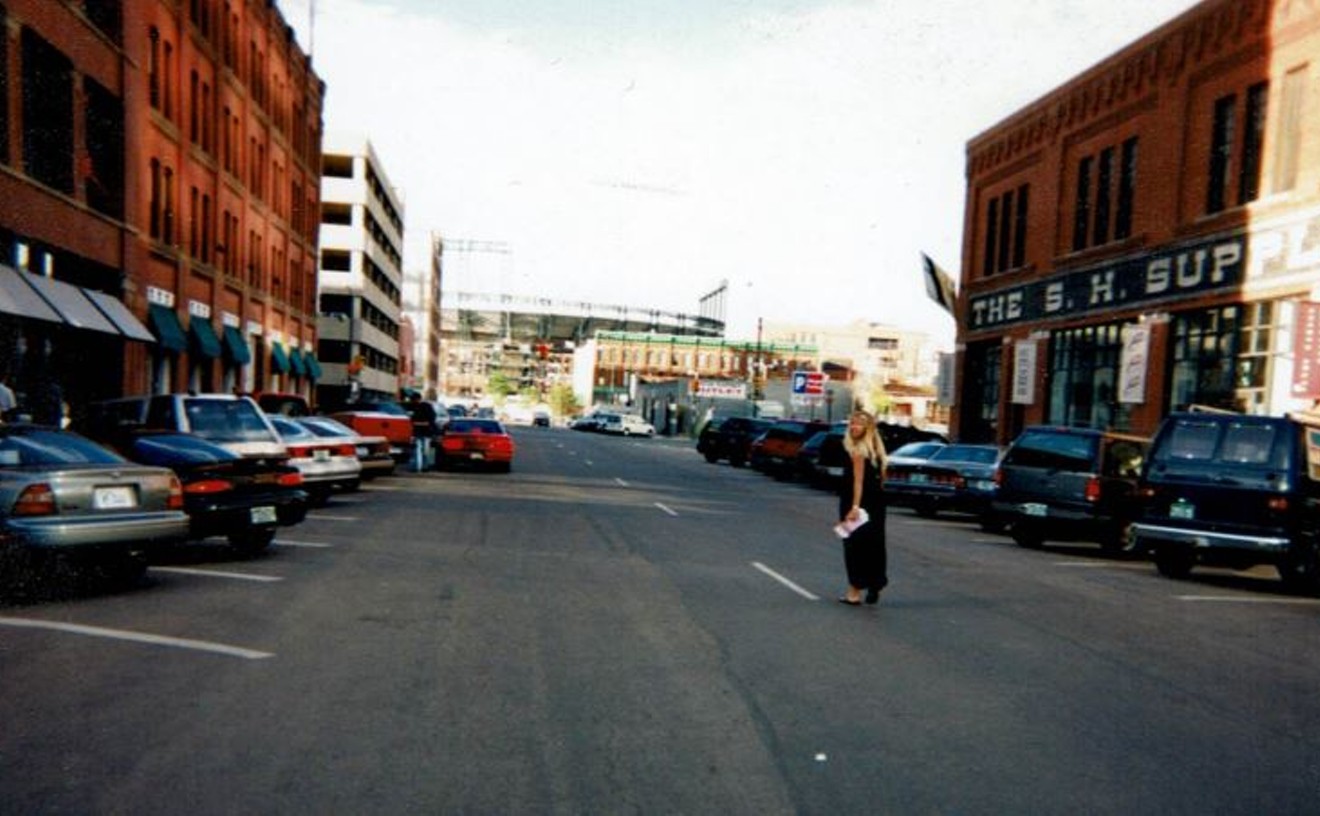

Brakhage played a big role in luring Solomon to Boulder, where he's been teaching at the University of Colorado since 1991. When Solomon was first dropped off in front of Brakhage's home over twenty years ago (by a young Trey Parker, no less), he remembers a man with a "fantastic Santa Claus laugh who would bear-hug everyone he saw" -- standing there with open arms, seemingly on the brink of entrapping Solomon in yet another of his infamous grizzly embraces.

"It was love at first sight," Solomon recalls. "He embraced me. We became best friends instantly. I was warned he would burn our bridges at one point or another, and it never happened."

In fact, from that point on the two shared a symbiotic relationship that Solomon calls "the most profound thing that ever happened to me." In the early stages of Solomon's career as a filmmaker, Brakhage was a role model, perhaps even an idol. Solomon remembers how he "worshiped his creativity and bravery" -- until they eventually exchanged films and began working together. Once they'd officially teamed up, Solomon says they were "just two guys jamming in Boulder."

Brakhage passed away in March 2003 after a drawn-out battle with cancer, and Solomon was devastated.But he now says that the bereavement, much like their relationship, led him to explore unexpected depths. And today, a decade later, Solomon is honoring his late friend by writing a book entitled A Snail's Trail in the Moonlight: Conversations with Brakhage.

Solomon plans to transcribe over 120 hours of videotape from Brakhage's Sunday salons, where once a week he and a group of film lovers would view films from Brakhage's personal collection and engage in lively discussions about them. In addition, Solomon says he's sifting through "nine years' worth of soliloquies" Brakhage left on his answering machines during their time together. And Solomon's artistic tributes to lost companions don't stop there. In the early part of the last decade, Solomon stumbled upon the video-game series Grand Theft Auto while teaching a CU postmodernism class. What he discovered was exactly what had captivated millions of teenage boys for years: a world of seemingly endless possibilities.

As a free-roaming mafia hitman equipped with guns and a plethora of civilian throngs and policemen to potentially destroy, your average Grand Theft Auto gamer tends to exercise (or abuse) his virtual Second Amendment rights. But not Solomon. Instead of exploiting cheats to obtain an arsenal of fully automatic firearms, he used them to "make surreal tableaus" that often included changing daily weather patterns. He was enthralled by the scenery -- the lakes, hills, abandoned buildings and anywhere else he could explore in peace. "I just looked around," Solomon says. "I wasn't interested in killing. If you just don't kill and stop to smell the roses, it's really quite beautiful in there."

Solomon worked on several different stages of the machinima-based series that incorporated imagery from Grand Theft Auto before finally completing a comprehensive piece in 2009 titled In Memoriam, which Solomon says included "very sad and lonely prayers in dedication to the memory of my friend."

But of all Solomon's artistic undertakings, none has been as strenuous nor time-consuming as his most recent achievement, American Falls, which Solomon describes as a "critical and poetic condensation of American history." Between its inception and completion, American Falls took twelve years to produce. It was originally commissioned by the Corcoran Galley of Art in Washington, D.C., and shown as an installation piece at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens this past October.

Solomon says the initial inspiration for American Falls came from a visit to D.C., where he noticed the vast number of memorials. But he also cites the influence of Frederic Church and his painting Niagara. Much of Solomon's artwork relies heavily on attribution, and American Falls is no different. Images from D.W. Griffith's America can be spotted, as can scenes from the original King King, North By Northwest and There Will Be Blood, among others.

The technicalities of American Falls are also quite extensive. As a triptych piece, the film is shown using three HD projectors. It has a complex 5.1 surround-sound design engineered by Seattle-based Wrick Wolff, who also composed many of the electronic keyboard passages that can be heard throughout the work. The movie is nearly an hour long, and its construction relied on a painstaking photochemical process; several of Solomon's former students assisted him with the production.

"Some people describe them as elegiac," he says of his movies. "They're kind of melancholy. They're very dreamlike. In dreams you don't really have hard cuts. It seems like dreams dissolve, from what I can tell. I want my films to imitate thought, feeling and the parts of the mind that are not just the storytelling mind -- the parts right before you go to sleep or when you first wake up."But winning that $50,000 fellowship was no dream.

Between a decade-long project he's still paying for and the financial bind endemic to the life of an artist-teacher in general, Solomon says the USA fellowship grant "could not have come at a more perfect time." The grant money will be spent in a holistic fashion, he adds, but most of it will go towards work and research, which he hasn't always been able to fully immerse himself in while teaching.

"It's very hard to do your own work during the school year because there are so many distractions," Solomon explains. "It's wonderful to be liberated from that and to just be able to devote my imagination and concentration to working on new material. It's kind of a wonderful coincidence of events that have happened."