Westword caught up with Saunders in advance of his trip to Denver, to talk about finding out which literature is bullshit, writing stories based on dream images, and how, creatively, it's always best to steer toward the rapids.

See also: Comedian Andrew Orvedahl on JG Ballard, George Saunders and airport books

Westword:Hi, George, thanks for doing the interview. How are you doing?

George Saunders: I'm good. I've been busy. Our water went bad, so it's actually been one of those days where we're just kind of waiting for the swarm of locusts to show up.

You're coming to Denver for the Lighthouse Writers Workshop? What do you have planned over the couple of days you'll be here?

We've got two big events. One is a public event with a reading and an on-stage interview, so that'll be fun. The other one is a smaller group, and from my understanding, it'll be focused more on writers. It's more of a technical discussion of the writing process over a two- or three-hour session.

So, as a professor yourself, how does it feel to have your own work so closely studied and analyzed?

It's really nice. You know, they could be studying nuclear physics or something more useful, but it's really nice. It really is an honor, but it's also kind of weird. This is actually one of the things I'm going to talk about in Denver: My approach is pretty intuitive. I mostly see myself as an entertainer, so the idea would be that if you're going to get anything deep in your work and worthy of analyzing, you first have to make it lively and really get your whole self in there. Not just your head -- your whole body and all your experiences. That's really 99 percent of what I'm doing; just trying to get the text to sit up and do something fun. So it's interesting to hear people's thoughts after the fact. I find myself telling people, "Oh, yeah, sure. I did that on purpose."

Of all the stories inTenth of December, the one that really stood out for me the most -- and it's funny that you mention trouble with your house, just like the protagonist -- was "The Semplica Girl Diaries." Where did you conjure up that haunting image of poor immigrant women strung up on the lawn like ornaments?

Oh, I dreamed it. I woke up one morning with that in my head, like, "What the hell?" The image was weird, but the really weird thing is that the person I was in the dream wasn't shocked or appalled -- I felt gratified, you know? So that was kind of the one-two punch of it; the weird image and my weird reaction to it. That really stuck with me. I think I wrote something down for the next day and then just kind of sat on it for a year while I figured out what I wanted to say. It ended up being a fourteen-year project, because I couldn't quite...the thing you have to do is make a world around that vision, and that took a little doing.

Unless I've got it totally wrong, it's one of the most scathing satires of the "keeping up with the Joneses" mentality, where you're conditioned into doing pretty questionable things by just kind of going with the inertia of capitalism.

I think that's what it is. That's what it was almost immediately, but over the fourteen years, I think what I was trying to do was try and figure out a way to soften, or at least complicate -- and what you said at the beginning was absolutely right, that was just me putting my autobiography in there, you know, all the details of his financial problems. If it was just going to be a scathing satire of capitalism, that's fair enough -- but in order to make it stand up, you have to make the guy sort of sympathetic.

That's what's so scathing. You have to get close to scathe. Did you ever read that comic strip Pogo? I don't know how old you are.

I haven't.

Well, it was actually even before my time, but the cartoonist was Walt Kelly. His character Pogo said this great thing; he says, "We have met the enemy, and he is us," you know, instead of "We have met the enemy and he is ours." I think that story to me was always about that. I had that in my mind. Whoever makes up this thing called capitalism, this thing which is so wicked -- well, it's not really "them," it's us. So that's what took time, to get to love that character a bit, so what he was doing was somewhat understandable.

It's clear that decorating your lawn with Semplica Girls is codified in his reality, but we're also so ground down in even the mundane concerns of home ownership. Even the way it's written, there's a real economy of language, like he doesn't even want to spend words.

Right. I had a series of diaries that I kept when my kids were little and I kind of lifted the style from that. They all have that kind of telegraphic thing -- mostly because I'd do it at eleven o'clock at night just before I was about to fall into bed. I had this kind of romantic idea about keeping a diary, but the reality was so tiring. Something would happen and I'd think, "God, it would take four hours to write that out," so I end up just kind of putting the bare bones down.

I read in your essay "Mr. Vonnegut in the Sumatra" that you used to hold pretty conservative beliefs? Reading Ayn Rand and drilling for oil?

Yeah.

So, did those beliefs subside over the years?

They change. I went to the Colorado School of Mines, and at the time, it was a pretty conservative place. So I absorbed that, and at that time I was not doing well in engineering school, I was really fighting to stay in there. I feel like sometimes when people have their back against a wall like that or, as I was seeing, they're seeing their own limitations then you tend to be a little more defensive. A lot of those conservative ideas are comforting. I found them comforting. After I got out of Mines, I went over to Asia and worked in the oil fields and that was kind of a re-education for me. To see real poverty; to see nice, good people really work hard and still be kept down. And, as part of the oil company, I could see just how we were doing it. The way that the national oil company of Indonesia would go into oil-rich areas and trample over everything, including people's property rights. Then they'd find oil and then all the income would go out, like 60 percent would go to Indonesia's national oil company, 35 would go to us, maybe 5 percent would go to somebody else, but none of it would go back into the local area. So I just got re-politicized a bit.

I could see how a basis in Ayn Rand would help insulate someone from questioning that.

No, that's right. I don't know what she actually stood for, but the way she landed in my mind was that power was its own justification. That's very appealing to an adolescent mind.

So, aside from Slaughterhouse Five, were there any other books that you remember reading that challenged your beliefs, either politically or your ideas about what literature was supposed to be?

I can remember leaving high school and thinking that I might want to be a writer, but not really understanding what was good writing and what was not. So I would read these poppy books, like Jonathan Livingston Seagull, or Khalil Gibran, Robert Pirsig, and then I would read Dostoyevsky and Walt Whitman. And Ayn Rand. I couldn't really tell what was good. To me, if it was published, it was good. So I think part of that was to go out into the world a little bit more and just get smarter. To be able to tell what was bullshit and what wasn't. At some point, when I read Kerouac, that really rattled my cage. I think it's because he was working-class. Especially a passage in Visions of Gerard that describes Lowell, Massachusetts. Something about that really got inside my perimeter, you know? Before that, I'd been a big Hemingway fan and somehow money, class and working never really comes up; everybody's just kind of fishing for trout or whatever. But with Kerouac, there were these descriptions of his dad who was a working guy and a drinker. You could just see that in that world, work was always encroaching on the spirit. And that made me uncomfortable in the same way that Springsteen songs do, partly because it's so close to home. But that was a big one for me. Reading Visions of Gerard while I was in Asia and getting the idea that a person's day-to-day life and their work isn't irrelevant to their spiritual state. Sorry, I haven't been interviewed in a while, so my answers may be a bit roundabout.

I was interested in that idea of what literature was supposed to be. For a lot of young men --and maybe women experience it, too-- but young dudes who fancy themselves to be writers find the Hemingway model hard to shake.

And he's great! I just read that story "Indian Camp" from In Our Time and that's a great story. All his excesses and personality quirks aside, when he was young he really had something going with his style. But, yeah, it is hard to shake. But I think for anybody, your first motion as a writer is to find two or three heroes that you love and you want to be in their crew. Then you imitate them, of course. Then the next step is feeling the difference between your view and their view, which is sometimes painful because theirs is fully formed, and theirs is iconic and you're just this dope. For me, that had a lot to do with just looking at the things that actually cost me something in my life and the moments that made me feel vulnerable and angry. All that stuff seemed to be about money or working. By this time, by the time I got around to my first book, I was older and I'd been working. And I got kind of a jolt to realize it. I'd been trying really hard to keep money out of my stories, to keep work out of my stories, because I couldn't think of anything interesting to do with it. And then at one point, when our kids were small, I thought, "What else is there, really?"

If I did a scan of my actual emotional life, there was nothing other than that -- especially at that point, because we were pretty broke. Everything is about my wife and kids and all of that is being colored by this incredible work regime we have in place and the fact there's not enough money coming. So in my gut, I concluded that it's got to be literature. If it's all I'm thinking about, it has to be, you know?

Yeah, whenever they publish authors' old letters, they typically leave out all the ones they sent to their benefactors asking for money.

When I was young, I was a real romantic, you know, Hemingway and Kerouac, Thomas Wolfe and Norman Mailer. I used to write a lot of letters and also journals. I found some of my old journals from when I was in my twenties, which I'd remembered as a really carefree, partying, wild time. When I went back, it was all about money. You know, "If I do this, I can get $60. So-and-so owes me twenty." It was so deflating, and kind of beautiful, too. In my mind, these were the wild years, but I was really like a little old man, counting quarters. Trying to put together the next trip. It doesn't go away, that's for sure.

So you were just interviewed for Mike Sacks's new book, Poking a Dead Frog. Do you consider yourself a humorist?

You know, I think the trick is not to consider yourself too much of anything. If you say, "All right, I'm a humorist" or "No, I'm not a humorist," then if some idea or opportunity could come to you, you might rule it out. The same thing with whether or not I'm an essayist or a fiction writer. I think the watchword is steer toward the rapids.

I'm working on this project now, a fiction project, and I'm really into it. I said to myself in one of those writerly moments, "Okay, you're not doing anything but this. Turn down everything else." So then I got up one morning and had an idea, partly in response to this guy's request, to set up mock liner notes, like for an album. I dreamed this crazy image and just couldn't help but go and start typing it up. I got up at like 4:30 because I couldn't sleep. So I wrote this kind of wild, funny piece, should I pretend it doesn't exist? No, so I sent it to the New Yorker. I like to be funny. Sometimes it is just a cheap-ass humor piece for grins, other times. like in "The Semplica Girl Diaries," the humor is more strategic for the dramatic structure. But for the most part, if somebody says, "You're a satirist" or "You're a humorist," or "You're a dope" I just say, "Okay." Whatever people want to put on you is fine, as long as you retain your freedom to go towards the rapids. Then, at the end, when you're 157, you can go back and say, "Well, at least I didn't waste any time."

But Mike Sacks, I couldn't believe how good that interview was. I think I told him every story I knew, basically. He cut it way back down, obviously, but I was looking at my computer just now and I sent him like fifteen separate files. He's a smart guy. His first book, And Here's the Kicker is really good, too.

Yeah, that's an important book among comedians and comedy nerds. Have you ever tried comedy? It's a real kick in the balls.

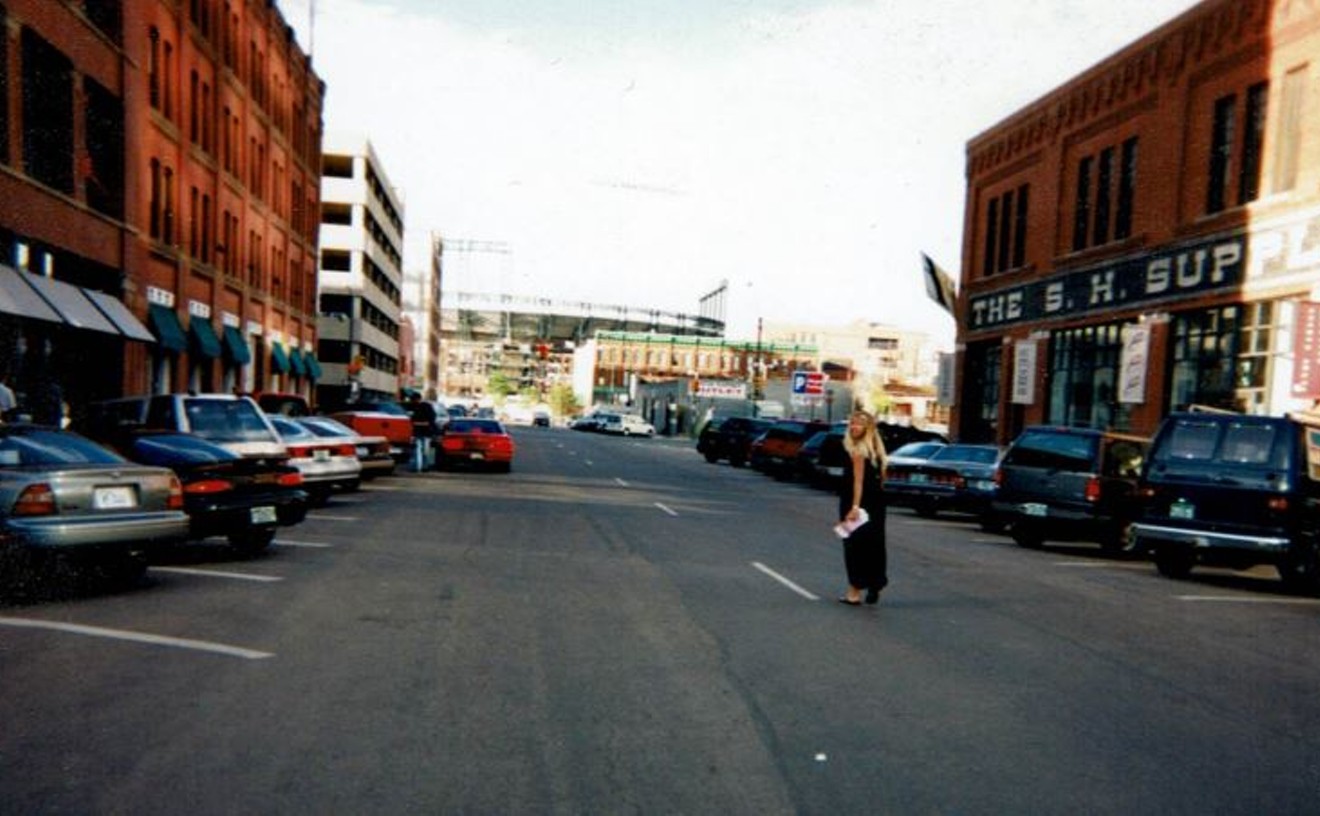

I did it one time out there in Denver and that was enough. Many, many years ago in the '80s at an open mic thing. It was a fiasco. Too scary. All the old comics were so terrifying. So bitter.

Comics are often profoundly unhappy people.

I was amazed. I remember being backstage with them, they worked real hard to put distance between themselves and the amateurs. Just these entirely unhappy, cynical guys. I think it was a more cynical time. I didn't enjoy that scene at all, it made me feel unclean. I'm sure it's all virtue now.

There's no money, but maybe there's more integrity.

I think it's an exciting time for young artists. Things have changed a lot.

I noticed that you mentioned using dreams for inspiration twice. Is that a regular habit?

No, if it happens I'm always so happy. It's almost like half the work is already done. I've only had it happen like maybe five times in my life. And the times when it hasn't happened, where you end up wasting two weeks on it, happen more often. So I don't always trust dreams as a source. I think that a dream and a story are similar, but in a story the secondary material is more organized. Most dreams, you know, it's like talking buttersticks and that's all, sometimes it's from a more alert place. The trick is to present it in some grounding form. I wish it happened more. There's a certain flavor to them when I know they're good.

It's seems fanciful and writerly, but I think there's a reason your brain does that.

A while ago, the New Yorker was putting out something highlighting the best twenty writers under forty, and there was going to be a big party, a big issue, and a big deal. And they said, "We want to include you in this, but we need a five- to six-page short story to go along with it," and at the time, I didn't have anything. I tried a couple things, and they didn't work. I think my subconscious was listening to this going, "Aw, you poor sap. Let me give you something." And it dropped this great thing, fully formed, on me because I needed it. I can't even guess how that shit works, but I can show up everyday.

A full pass to the Writer's Studio with George Saunders costs $80 for members and $110 for non-members, but the September 21 workshop classes are already full. The reading/signing on Saturday, September 21 is still open, though; tickets for that cost $20 for members and $30 for non-members. Doors open at 4 p.m. at the Mizel Arts & Culture Center, 350 South Dahlia Street. For more information, go to the Lighthouse website.

Follow Byron Graham on twitter @ByronFG for more mildly amusing sequences of words.