Art with a political edge is a specialty of the Myhren, reflecting the interests of gallery director Shannen Hill, the DU art historian who runs the place. Hill's scholarly focus is what she calls "the art of the African Diaspora," which includes, but is not limited to, African-American art. Colescott and Ligon are prominent African-American artists, making the pairing a natural for Hill. But there is more of a subtext to this political show than just African-American content, as indicated by the title's reference to the Logan Collection.

Named for Kent and Vicki Logan, prominent collectors of contemporary art who maintain a seasonal home in Vail, the collection comprises substantial fractional gifts made to the Denver Art Museum. The largesse of the Logans -- their gift includes more than 200 pieces -- has been shown off in part at the DAM, in last year's Retrospectacle and in Full Frontal, currently on display on the museum's fifth floor. Colescott & Ligon is the first in a planned series of exhibits that will explore the DAM's Logan Collection at the Myhren.

This new partnership is quite a deal for DU, and the idea for it came from Trygve Myhren, a DU donor who helps underwrite the gallery named for his wife, Victoria. "Victoria and Trygve have a personal friendship with the Logans, and they really did make this happen in a big way," Hill says. It was just last spring when the Myhrens suggested the idea to the Logans, and, by summer, Hill was taking on the task of organizing this first show.

Because Colescott and Ligon are stylistically very different from each other, at first I wondered if their work would look good together. After all, Colescott's pieces are expressionist and sloppy, while Ligon's are mechanical and crisp. I'm amazed to report that in spite of these antithetical qualities, the pairing is absolutely stunning.

Colescott, who came to the fore of national contemporary art back in the 1970s and '80s, is the old master, so it seems right to start with him. Associated with a whole generation of neo-expressionist painters, Colescott put a personal twist on the movement by including, among other things, racist caricatures in his paintings. He's quoted in the show's catalogue as saying that his work is "not about race," but "about perception," and caricatures are the ideal means to carry out that program.

There are half a dozen Colescotts in the show, the most significant of which is "School Days," a major acrylic on canvas from 1988 that depicts grotesque cartoons of students, most of them black, with one aiming a gun at the viewer and another having exaggeratedly bulbous lips. Also remarkable is the painting's rich palette of deep green, yellow and red tones. Interestingly, "School Days" is not a Logan Collection piece; it was given to the DAM by Nancy Tieken, an important donor who no longer lives in Denver. As Hill explains, the Logan Collection pieces form the basis of this show, but objects from other collections were used to supplement them.

The Ligons come right out of neo-pop, and in many of them, Andy Warhol's influence is undeniable, particularly in "Hands," a silkscreen-ink-on-canvas diptych from 1997 that's more than twenty feet long. Also very Warholian is "Malcolm X, Sun, Frederick Douglass, Boy With Bubbles (version 3) #1," from 2000. Some of the Ligons are more conceptual than pop, as in the series of ten lithographs from 1993 collectively titled "Runaways," in which antebellum illustrations of slaves are combined with reprints of newspaper ads from the period offering rewards for the missing individuals.

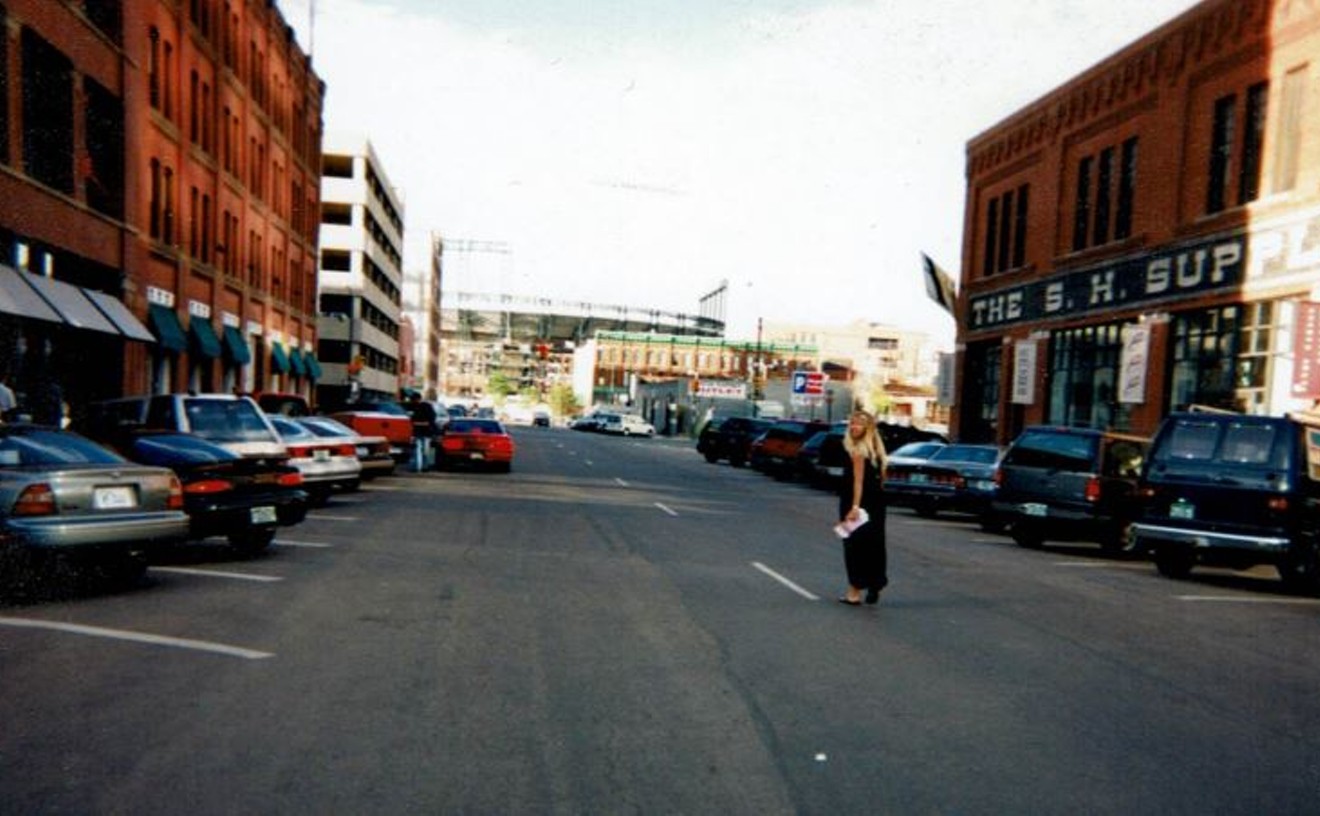

Kent and Vicki Logan have been doing a good deal for the art world in Colorado (and in their other home state, California), so it would be foolish of us not to take advantage. Hill says attendance has been light, so many haven't yet done so. I know it's a nightmare to park on the DU campus, but I assure you, this show is worth the trouble.

Not far from DU, at the Mizel Center for Arts and Culture, the situation is very different -- and not just because there are plenty of parking spaces. The current shows there have been drawing big crowds because of the mass popularity of their shared topic: the art of comic books. In the Singer Gallery is No Joke: The Spirit of American Comic Books, and in the Balcony Gallery is No Yokel: The Spirit of Denver Comic Artists. Even if you're not particularly interested in comics -- and I'm really not -- there's a lot here that's intriguing.

Singer director Simon Zalkind conceived the show together with former Mizel director Joanne Kauvar. "I could not have done this show were it not for Joanne," he says. The show has been arranged in chronological order, starting to the left of the entry and then wrapping around the room and ending on the right. It's no exaggeration to say that it's an impressive accomplishment.

Zalkind surveys comic books from the beginning by using rare original drawings instead of the deluxe signed reproductions that are widely available today. He even decided to forgo including comic books themselves. "In the golden age -- the '30s and '40s -- no one considered that these drawings would hang in galleries one day," Zalkind says. "The publishers used them to make the comic books, and then almost all of them were thrown away because they were thought to be worthless. Of all the shows I've done, original comic-book art was the hardest material to come by. Collectors of comic-book art don't necessarily feel the need to share the work with the larger world the way art collectors do -- they really put the "fan" in "fanatic" -- and the people I contacted at first didn't want to lend things."

To solve the problem, Zalkind felt he needed to find someone who had credibility with the comic-book-art collectors, so he got in touch with underground-comics artist Dennis Kitchen. "Dennis put his imprimatur on the show, and the project became feasible," Zalkind says. "Prior to finding him, I was getting nowhere."

The Mizel Center is a Jewish institution, and it is housed in the Jewish Community Center, which is an appropriate setting for this show because, as it turns out, many comic artists were Jews. "It was a marginal industry, so it makes sense that Jewish immigrants, who were also marginal, would be attracted to it," Zalkind says. "The industry itself was mostly located on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a predominantly Jewish area."

Since many people in the art world have no background in comics, Zalkind came up with a brilliant idea for didactic content: a mural painted along the top of the walls by Denver comic artist Tom Motley and a crew of other local cartoonists. It tells the history of the comics in comic-book style, of course. "I paid them in pizza," Zalkind says. "Three hundred dollars' worth of pizza."

If, like me, you know little about comics, it makes sense to circle the gallery first and "read" the comic-history mural, then orbit the room again to take in the spectacular original pieces hung at eye level. You don't have to be into the comic-book subculture to appreciate how good and engaging many of these drawings are from a fine-art standpoint.

"This is the comic-book version of El Greco to Picasso," says Zalkind, "with Joe Shuster being El Greco and R. Crumb, Picasso."

Shuster is one of the inventors of Superman, and a large drawing by him starts off the show. Crumb, of course, was a pioneer of the underground movement in the '60s. But there's a lot more than that. There's "Boy Commandos #3," by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, from 1943, which Zalkind sees as being so important he describes it as "a destination piece." And there are major works by Will Eisner, who attended the opening, as well as by many other masters of the earlier eras, including Lewis K. Fine, Jack Burnley, Jack Cole, Frank Frazetta and John Severin, who lives in Denver.

There's a small section devoted to the artists associated with Mad Magazine, and other Mad artists are sprinkled through the second half of the show. They range in date over the magazine's entire history, with a 1950s Don Martin, "The End of a Perfect Day," being the oldest, and a 2002 Drew Friedman, "What If Chris Rock Performed at a Bar Mitzvah," being the newest. In addition to Crumb, other major figures from the period are also in the show, including Art Spiegelman, whose work blurs the distinction between comics and the fine arts, and Howard Cruse, a rare example of a gay comic-book artist.

No Yokel takes a brief look at local comic-book artists, thus providing a good chaser to the big show. This group was put together by muralist Motley and includes his work along with that of a number of others, notably Harry Lyrico and Al "Owl" Newman.

No Joke and No Yokel are so densely installed and so chock-full of artworks that viewers could literally spend hours here, especially if they want to read all the captions. Or they can do what I did and take a reasonable amount of time to enjoy them. Either way, these are two exhibits that many people, both inside and outside the art world, will want to see.