The music industry and how music is disseminated these days is quite different than when Echo & the Bunnymen released significant albums like Porcupine and Ocean Rain in the 1980s. Guitarist Will Sergeant says that everything’s changed; the whole ballgame has changed.

That’s why the band, which released its twelfth full-length (Meteorites) in 2014, is considering next releasing an EP or a series of EPs and holding off on an album for now. Sergeant says he and frontman Ian McCulloch are in the middle of deciding what to do with the new material. “We’re just writing stuff and seeing where it takes us and seeing how it goes,” he says.

When they do eventually release the new material, they’ll be putting it out to a music world that’s, as Sergeant says, more interested in a single than in buying the full album.

“Attention span — it’s gone out the window, because everything’s instant,” Sergeant says. “They’ll play like ten seconds of a song and go on to something else. It’s like, slow down a bit. Give it a minute.”

Sergeant says there are some great advantages to the Internet, like being able to get music instantly, but it’s also turned music into a commodity. He says music just doesn’t have the same value as it once did.

“Like when Pink Floyd had an album come out, it would be like a major deal for me,” Sergeant says. “Or Roxy Music or Davie Bowie. It’d be a big thing. Now, nobody seems to give a shit. It’s all changed. Everything’s on iTunes. Those people just buy the single. So you’d spend a load doing a load of tracks. It’s like a body of work and then people would just buy the single. All the other ones are seen as substandard. But to me, some of the best tracks have been on Bowie records or Lou Reed or whatever, you know, it’s been the ones that weren’t the single.”

Take “Perfect Day,” from Reed’s 1972 album Transformer, for example. Sergeant says it’s always been his favorite Reed song. But in 1997, a version of the song was released for the charity Children in Need and featured singers like Bono, Suzanne Vega, Shane MacGowan and even Reed himself singing lines from “Perfect Day," and the song essentially went from a deep cut to a hit, at least in England.

“Everybody sang a line and all that stuff, and it became, like, this great song by Lou Reed,” Sergeant says. “People who were into Lou Reed knew about it for centuries. So it became sort of the thing. That’s what most people know about him now, ‘Perfect Day.’ And it was sort of a charity record over here. I don’t know if it ever made it to America. It became like everyone had heard of it. Lou Reed fans had known about it for donkey’s years.”

For years, Sergeant has been a fan of Reed and the Velvet Underground, and Echo & the Bunnymen has covered a few of their songs. Growing up, the music of Bowie and Pink Floyd were important to him as well. These days, Sergeant questions who’s got the same kind of stature as those bands

“Nothing,” he says. “I can’t think of anything. What? Coldplay? I don’t know, Maroon 5. What’s out nowadays, I don’t even know. When we were getting into music, if somebody asked me what Number One [on the charts] was, I’d be able to tell them. Now, nobody knows. Nobody’s interested. It used to be a major event. The countdown to the charts on a Sunday night. I’d tune in to the radio and all that over here in England. It’d be like a thing, you know? You’d be rooting for your favorite band to be up the charts a bit. Now nobody gives a shit. It’s just like another bit of wallpaper in people’s lives, really, now. It was a lot more important when we were sort of growing up. That’s why punk was so important at the time. You couldn’t have another punk thing now. It’d just be like another silly fad.”

Echo & the Bunnymen formed in 1978, two years after the punk explosion in England. Over nearly four decades, the band has gone through lineup changes since its early beginnings of McCulloch, Sergeant, bassist Les Pattinson and a drum machine, along the way releasing hits hits like "Rescue," "The Cutter," "Bring on the Dancing Horses," "Lips Like Sugar" and "The Killing Moon," which Sergeant says might possibly be based on the chords of Bowie's "Space Oddity," only backwards, but he can't remember exactly how the song came together. These days, McCulloch and Sergeant lead the lineup, with touring members bassist Stephen Brannan, guitarist Gordy Goudie, keyboardist Jez Wing and drummer Nicholas Kilroe.

“I can’t believe that we’ve been doing it for this long and [are] still doing it,” Sergeant says. “I’m still enjoying it. That’s the whole thing. It’s like it’s not like a chore. It’s not, ‘Oh, God, I’ve got to do another Bunnymen record.’ It’s like, ‘Yeah, I can’t wait.’”

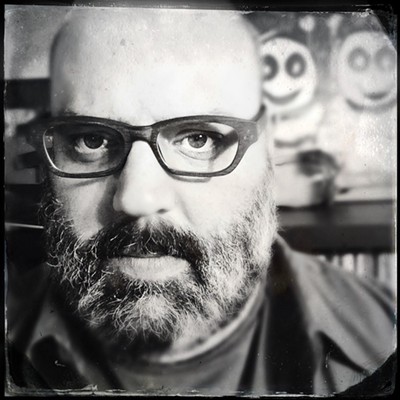

The 56-year-old Sergeant says he’s had people ask him if he feels a bit weird still touring in a band since he’s getting on in age.

“I go all around the world,” he says. “I play to people that love us. Songs that I made or helped make. And people love them. And we get paid for it. And you’re working in a factory in Speke [near Liverpool] or somewhere. And it’s like you’re asking me, ‘Don’t you feel crap about doing it?’ No, I don’t. It’s amazing. It’s like the best job in the world ever.”

Echo & the Bunnymen performs on Tuesday, September 20, at the Ogden Theatre, 303-832-1874.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]