After more than two decades of living in the United States, synthpop pioneer Thomas Dolby (due at the Bluebird Theater this Thursday, November 14) returned to the coast in Suffolk, England, where he grew up and later built a studio called Nutmeg of Consolation in a 1930s lifeboat, and that's where he recorded his latest effort, Map Of The Floating City . When Dolby found out a that the lighthouse which flashed its light on his bedroom wall as a child was due to be closed, he started making a film about it called The Invisible Lighthouse, which he's showing on his current tour.

See also: The best concerts to see in Denver this week

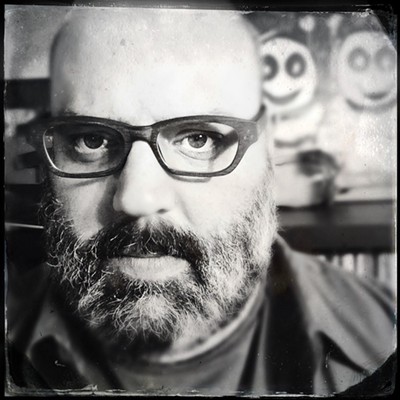

Along with screening the film, he offers live narration with a musical score linking songs from various stages of his career. We spoke with Dolby about the film, his latest album, Map Of The Floating City , and his thoughts on the recent passing of Ray Dolby, the father of modern noise reduction.

Westword: With the Invisible Lighthouse, it seems like the inspiration for it came about when you moved back to Suffolk, finding out that the lighthouse was closing and also rediscovering your childhood memories there, right?

Thomas Dolby: Yeah. When I started the film I really didn't know what it was going to be about. I heard the lighthouse was going to close and I just started filming within a ten-mile radius of my house. At first, I was just doing it on my iPhone and talking into the phone like vlog, and then I looked at it and thought that maybe there's a story in here somewhere.

I sort of imagined that I'd hire a professional camera person to come and shoot it properly, but I spent an afternoon with a professional camera person, and I looked at it and thought, actually, I don't like it is much as the iPhone footage because it has this sort of confessional quality to it because I'm walking around the countryside and sort of remembering things from my childhood, and I'm realizing that I remembered them all wrong.

I bought a kit, and these days you can get amazing equipment that's capable of doing very high quality stuff for $200. Being a bit of a geek, I got into GoPro accessories and spy cameras and a quadcopter camera that you fly from your smartphone and things like that. It's coming together. I taught myself to edit on my laptop, and I would just sort of speak narration into the laptop, and it was quite minimal. It was sort of like a tone poem And that's how it came together.

You talked about doing sort of covert missions where there are unexploded warheads and that kind of thing. Was that ever scary at all?

I mean, I went through the proper channels to get out to the island to do some special filming. You could go out with a guide, but you had to stay on the special tracks on the path and so on. But I wanted to be able to wander around on my own, and I wanted to try to get out there and spend the night on the island the last night of the lighthouse.

I got so little cooperation from the authorities, it almost amounted to sort of sabotage. So I just thought, well, I'll take the law into my own hands and do a clandestine commando raid on the island with cameras rolling, and maybe that will make an interesting climax to my film.

From what I understand, part of this tour is letting people know that are these lighthouses around the States, and the U.K. that are abandoned, right?

Yeah. Well, generally speaking they're trying to close lighthouses down because ships have got satellite navigation these days and radar and things. Weekend yachtsmen have got better stuff on their phones than they can get from lighthouses. Lighthouses, in the big picture, are like a transitional technology between terrestrial navigation and the smart phone.

But it's very sad because they've given us so much -- in the case of this country, they've been around, some of them nearly as long as the USA has been around. And I just feel they should be preserved, and in an age where you're worried about sort of fiscal shutdowns and things you don't understand, why people might devote a lot of time to that, but we're really going to miss them when they're gone.

A lot of people have a soft spot for a lighthouse in their past, or a building, or a park, or a mountain, or a creek, or whatever it may be. A lot of people's childhood memories are really wrapped up in these favorite places. So I think when people come to see my show, it touches a nerve because I think we've all got something like that in our past. Also, as you get older, you begin to question how much things sort of candy coated our memories.

You were living in the States for about twenty years or so?

Yeah, I think 23 years.

So when you moved back to England, did some of those childhood memories come back to you once you got back to the place where you grew up?

Yeah, absolutely. A lot of it is because I've brought my family back to Suffolk to experience some of what I had as a kid, and of course, a lot had changed. You tend to get sad and nostalgic about that, but you have to let it go, really. For example, the lighthouse is closing down, but during the last few years that we've been back in England, we've seen the largest wind farm in Europe has been constructed just on the horizon from the beach where we live.

And this is kind of wonderful because I wrote a song called "Windpower" in 1980, and I've always been a champion of alternative energy. I've been watching from my studio with a telescope; there's these extraordinary vessels that take giant turbines out and gradually building about a 150 of them out on the skyline.

And your studio that you built in the lifeboat is both wind and solar powered, right?

I bought it on eBay, and put in my garden, and it had a diesel engine in it, but I replaced that with a bank of batteries, and there's a turbine on the mast and solar panels on the roof. The studio is powered completely by alternative energy. So, during the day, as long as there's a lot of wind and sun, I can work all night.

You've also talked about how film is at a point now where you can make a film for a few hundred bucks, and you kind of compared it to how the music industry started its own DIY thing.

When I started out in the music business, it was just starting to change to a point of where instead of needing a recording studio and therefore a budget and a record contract to get a record made and out, you could start to things in your back room, you know? I sort of built my own drum machine and used to record my own demos, and had a couple of those, actually, released without needing a big studio. Every year, it seemed like there was a new kit coming out on the market that made that easy. Eventually, in the '90s, the internet arrived as a way to distribute music without needing record pressing plants and trucks and so on.

But I think it's been really liberating for a lot of young musicians starting out that instead of having to fight the industry they can just get on and make their music and get it out and hope that the audience finds it way to hearing your music. I think a lot of people think that the moment that happens, they're going to turn into superstars, and they may be wrong, but at least they've only got themselves to blame and not some record company's secretary failed to pass a cassette onto an A&R man. So I've been in favor of changes in technology in the music industry, and I think it's really starting to happen in the film and video world now as well and I love being part of that wave.

You've obviously embraced technological advances with instruments, synthesizers and software and that sort of thing over the years. Is it nice now to just have to carry around maybe one keyboard and a laptop rather than having to lug around quite a few synthesizers?

Oh yeah. It's a huge burden off my back that I don't have to lug them around. I mean, people get nostalgic about them, but I actually welcome the fact that I can just do it all on my laptop now. It's partly the weight and the expense and so on. But it's partly also the fact that were so many wires and knobs and things and cables that could wrong.

If you were working on a piece and go get some sleep or get a bit to eat, it was like a stack of cards: You just worried that it was all going to fall to pieces. So you were reluctant to leave it alone. Before you were to focus on one piece at a time, but now, I can have half a dozen pieces going simultaneously, and just save and record, and you come back sounding the same way as how you left them.

Your last record, Map of the Floating City, was sort of inspired as well by your moving back to England, right?

Yeah. I'm very influenced by the environment of where I am. If you think about it, a lot of my songs are about geography, about the planet, about weather conditions, environmental conditions, space, the earth, etcetera. And I've always steered clear of sort of in-the-moment relationship songs. So yeah, moving back to England was a very emotional thing for me. As I sat there on my lifeboat writing the songs, I was obviously very caught up in what was going on around me.

Can you talk about the three sections that make up the record?

It was always my intention to make it a complete album, but the songs seemed to fall into three categories: Oceania, Americana, Urbanoia. Americana was sort of a fond look back at the time I was living in America and the fact that the genre that we call Americana sort of comes down through a folk music tradition and obviously branched into country and bluegrass and all that. On a certain level, it's indigenous American music, but you can also view it as stories told around a campfire by travelers passing through from one person to another.

And so from that point of view although I'm not American. I have sort of as much right as anyone else to sit at the campfire and tell my own story and sing my own song. Things like "17 Hills," on the surface, sounds like it's got a lot in common with sort of folk lament -- lots of verses coming back to the same refrain about 17 Hills, and there's a jailbreak, and there's a murder and so on. So it's very much sort of joining that fabric of traditional American music, but it's clearly sung by an outsider -- it's sung by an English guy who has his own point of view on things.

It made a lot of sense for me to get Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits to play on that because he, like me, is a visitor to these shores and has written his own songs like "Sailing to Philadelphia" that very much fit in with American music, but he's really an outsider.

Ray Dolby passed away in September. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on him. And it was your classmates that nicknamed you "Dolby," right?

I respected the guy a great deal. We had our differences. I mean, he didn't like when I first emerged on the scene. He thought that I was using his name to gain an advantage. Of course, that wasn't the case. Dolby was my nickname when I was at school, and it just stuck. I had no intention of trying to cash in on his brand. But he was a remarkable man, and his achievement was that he created this brand that held its value over five decades or something. It was really incredible.

Early on, Dolby's sound only really applied to cassette tapes, and of course, when they went away, the challenge would have been to sort of evolve the brand into a different area, and I think he did that successfully with cinema sound and home theater systems and things like that. So I think his marketing achievements were almost as great as his technical achievements.

Follow @Westword_Music