In early 2016, we told you about the Western Slope arrest of former Texas death-row resident Claude Wilkerson for allegedly keeping a woman chained to his bed and repeatedly raping her. Just over two years later, Wilkerson has agreed to a plea deal in the case, and it's a sweet one. He's admitted guilt to a pair of lesser charges, for which he'll serve just six years behind bars and three on probation — an astonishingly brief sentence given the initial description of his crimes.

Details of the 1978 triple murder that resulted in Wilkerson's being condemned to death in Texas can be found in a 1988 appeal by David Roeder, who was also convicted in the case.

We've included the narrative section from the complaint below. But in brief, Wilkerson was among a group of men found guilty of killing three people — pawn shop owner Don Fantich, jewelry store owner Georgina Rose and Dr. William Fitzpatrick — in a robbery and kidnapping gone very wrong.

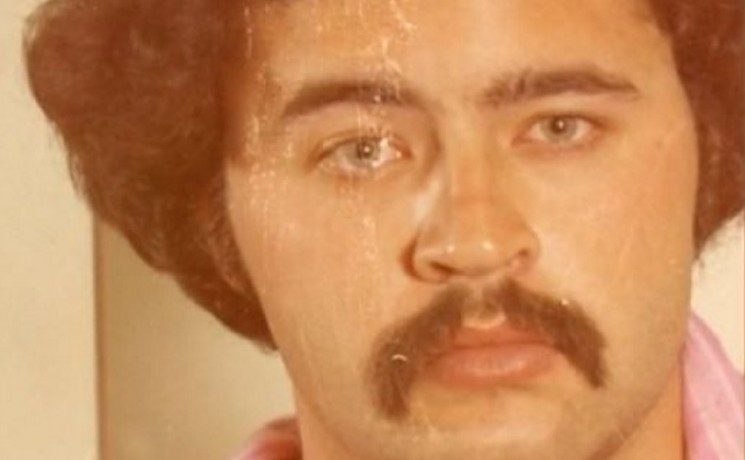

Wilkerson didn't personally take part in the killings. A 1983 Time magazine piece featuring the headline "The Death Penalty: 'I Don't Think I'm Guilty'" points out: "Texas law-enforcement officials and Claude Wilkerson, 28, agree on one point: when the murder for which he was later tried, convicted and sentenced to death took place, Wilkerson was locked up in Houston's Harris County jail."

Nonetheless, Wilkerson acknowledged to police that he had been part of the original crime — and as such, he was punished as if he'd pulled the trigger personally.

But the conviction was overturned. According to a 1983 UPI article, an appellate court determined that his confession had been coerced and that the judge in the original case shouldn't have allowed it in court because Wilkerson had repeatedly said he didn't want to talk to authorities without a lawyer present.

That year, Supreme Court Justice Byron White, who was originally from Fort Collins, refused to let officials keep Wilkerson behind bars while the state pressed its own appeal — which was ultimately unsuccessful.

After being released and exonerated, Wilkerson relocated to western Colorado, where, as the narrative below makes clear, he already had roots.

In the decades since then, Wilkerson kept a much lower profile. But that was before his arrest on the 400 block of Foy Road in Gateway for first-degree kidnapping, sexual assault, contributing to the delinquency of a minor, false imprisonment and harboring a minor.

According to Wilkerson's arrest affidavit, authorities stumbled upon the twisted scenario after Mesa County Sheriff's Office deputies responded to reports that a runaway had been found.

The girl said that Wilkerson, who she knew as "Chay," was keeping a woman tied to his bed — and that she'd helped him bind her.

She added that he'd threatened to kill her if she blew the whistle on them.

A deputy subsequently met with Wilkerson and the woman, whose mannerisms struck him as troubling.

So, too, did her request to be arrested on an outstanding warrant in her name, valued at just $50.

During a subsequent interview, the woman said she'd been homeless when Wilkerson offered her a place to stay the previous October in exchange for work around his home

Instead, she says, the runaway girl pressed a rag soaked with engine cleaner to her face in an effort to subdue her. Meanwhile, Wilkerson allegedly attempted to wrap her feet with wire, but when she managed to kick free, he opted for a tow chain he used to attach her to the bed.

The affidavit quotes Wilkerson as saying he was a "Shaman" who could see the devil inside the woman — and he needed to keep her chained until the demon departed.

With just a few exceptions (a handful of trips to the back yard, two visits to a store in Gateway), the woman said, she was kept chained for months. Over that span, Wilkerson raped her frequently, she told law enforcers. And these assaults weren't the only reason she feared for her life.

An excerpt from the affidavit reads: "He also would often claim that he was a serial killer. She said because of the way he chained her and treated her, she believed it to be true that he was a serial killer."

She added that "she was treated like a pet...and would be rewarded with good behavior." At Christmas, for example, she said Wilkerson gave her a marijuana pipe and a coloring book.

Wilkerson was held on a $1 million bond — a symbol of the seriousness with which authorities took the case. But prosecutors reportedly settled for much less than they'd originally envisioned. This week, Wilkerson confessed to second-degree assault, a felony, and false imprisonment, a misdemeanor — hence the prison jolt of just six years.

Here's the account of Wilkerson's original death-penalty case:

DAVID ALLEN ROEDER v. STATE TEXAS (12/29/88)

COURT OF APPEALS OF TEXAS, FIRST DISTRICT, HOUSTON

December 29, 1988

On January 23, 1978, appellant, Claude Wilkerson, and Mark Cass went to the home of Don Fantich. Under gunpoint, Fantich opened his safe and gave Wilkerson the cash inside. While they were there, Dr. William Fitzpatrick called and was told by Wilkersn to come by the house in hopes that he would be bringing drugs to Fantich. After Fitzpatrick arrived, Fantich and Fitzpatrick were taken in Fantich's car to a jewelry store owned by Georgiana Rose. Cass stayed outside in the car with Fitzpatrick while the others went into the jewelry store. They robbed the store, abducted Rose, and all three of the victims were taken to appellant's apartment. Appellant's roommate, Bobby Avila, arrived and agreed to help watch the hostages. After a discussion, it was decided that the hostages should be taken to appellant's parents' ranch in Shiner, Texas. Appellant, Avila, and Cass took them to the ranch.

The next day appellant and Cass went into town and tried to reach Wilkerson by telephone. On the way back to the ranch, they purchased a bag of lime. When they returned, appellant, Cass, and Avila decided that they would have to shoot the hostages. Appellant and Cass chose a place to bury them and dug a hole. The three of them then took the hostages to the hole. They agreed that each would shoot one of the hostages. On a signal, they fired. Appellant shot Fitzpatrick; Avila shot Rose; Cass shot Fantich. They put the bodies into the hole, put lime on the bodies, and buried them. They left the jewelry and guns in the attic of the house and returned to Houston. On the way back to Houston, they burned Fantich's car.

On January 26, 1978, Wilkerson told them to leave town and gave appellant $300. Appellant and Cass returned to the ranch, covered the grave with some branches, buried the jewelry and guns in several locations in the barn, and left for Grand Junction, Colorado, where both were later arrested.

In his first point of error, appellant contends that the trial court erred in admitting evidence seized during an illegal, warrantless entry into his apartment by police in violation of his rights under the Texas and United States constitutions.

During the afternoon of January 27, 1978, Claude Wilkerson confessed to his participation in the robbery and kidnapping of Fantich, Fitzpatrick, and Rose. He also implicated appellant in the crimes and told police that the last time he saw the victims was on the night of the robbery at appellant's apartment, four nights earlier. About 8 p.m., Wilkerson took the police to the apartment, but the officers did not attempt to enter the apartment at that time.

Around midnight, the officers returned to appellant's apartment purportedly in search of the victims although the officer testified that he believed that they were probably dead. The police did not have a warrant, nor is there an explanation in the record as to why they had not obtained one.

Lights were on in the apartment, and music was being played loudly. After no one responded to their knocks, the police went to an upstairs apartment where appellant's sister lived. Her name had been discovered on a mail box. She told the officers that appellant had gone to Grand Junction, Colorado, but she did not know whether Avila (appellant's roommate) was in the apartment.

The officers contacted the apartment manager to open the apartment; however upon entry, no one was found. The officers then called for a special investigator to conduct a thorough search of the apartment. In the search of the apartment, the officers recovered a gold chain with the price tag on it, duct tape that had been used and thrown away, and registration papers for appellant's car. Around 2:30 a.m. January 28, 1979, during the officers' search, Avila returned to the apartment and was placed under arrest.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]