Chance had discovered the smell after he’d driven by the house and noticed that the front lawn was dying. He was annoyed that his tenants weren’t taking care of the yard; since a leasing agent took care of renting the place, he’d never interacted with them. But now he parked, stepped onto the property and rapped on the front door. No one answered. He tried his key and was surprised to find that the lock had been changed. He found the same thing with the back door — only there, he was overwhelmed by the odor.

Assuming the worst, Chance called the police. At 8:40 p.m. on June 23, 1968, two Denver police officers arrived at 1050 South Elmira Street. They concurred with the landlord’s assessment: It smelled like there was a dead body inside the building. With Chance’s go-ahead, the officers broke one of the windowpanes in the back door and reached through the shattered glass to unlock it.

The upstairs of the house was clear.

But as the officers crept down a staircase into the basement, they encountered an unusual sight: dozens of cases stacked against a wall, empty trash-can-sized barrels, a sophisticated tool bench, plastic hoses that ran from a bathroom under two padlocked doors. That’s where the smell seemed to be coming from.

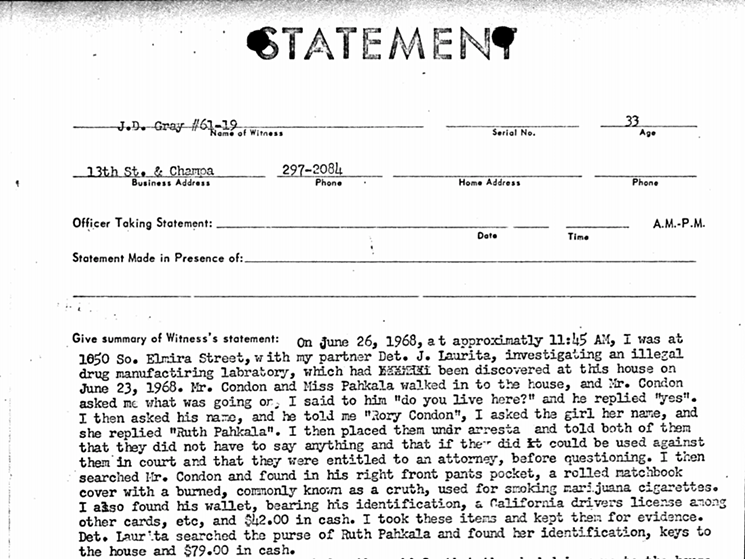

The cops called for backup, and Denver Police Department detectives Jim Laurita and John Gray showed up to investigate. With Chance’s permission, they busted through the padlocked doors, ready for anything.

They did not find a body.

Instead they found a laboratory. It was a sophisticated setup; the rooms contained flasks, tubes, beakers, mounted glassware and containers of all shapes and sizes filled with chemicals. Both narcotics detectives, Laurita and Gray knew that they had just uncovered a massive drug lab. When they returned the following day with a signed search warrant, they cased the rest of the house and discovered letters, journals and prescription bottles suggesting that three individuals lived inside the house.

On a search inventory list, they included this line item: “#23: Personal files of R. Timothy Scully.”

The name didn’t mean anything to them at the time, but the DPD detectives would later learn that Tim Scully was one of the country’s most important psychedelics manufacturers. A known associate of West Coast LSD impresario Owsley Stanley and the Grateful Dead, Scully was already being investigated by federal agents in California. No one knew that he had secretly moved his operation to Denver the year before, running a lab in a City Park neighborhood that had produced hundreds of thousands of hits of pure, crystalline LSD.

Today, fifty years after the Summer of Love, it’s still a little-known fact that Denver had been home to two major LSD laboratories. Even though the operations were short-lived, they created significant repercussions — not just legally for their operators, but for the psychedelic movement as a whole.

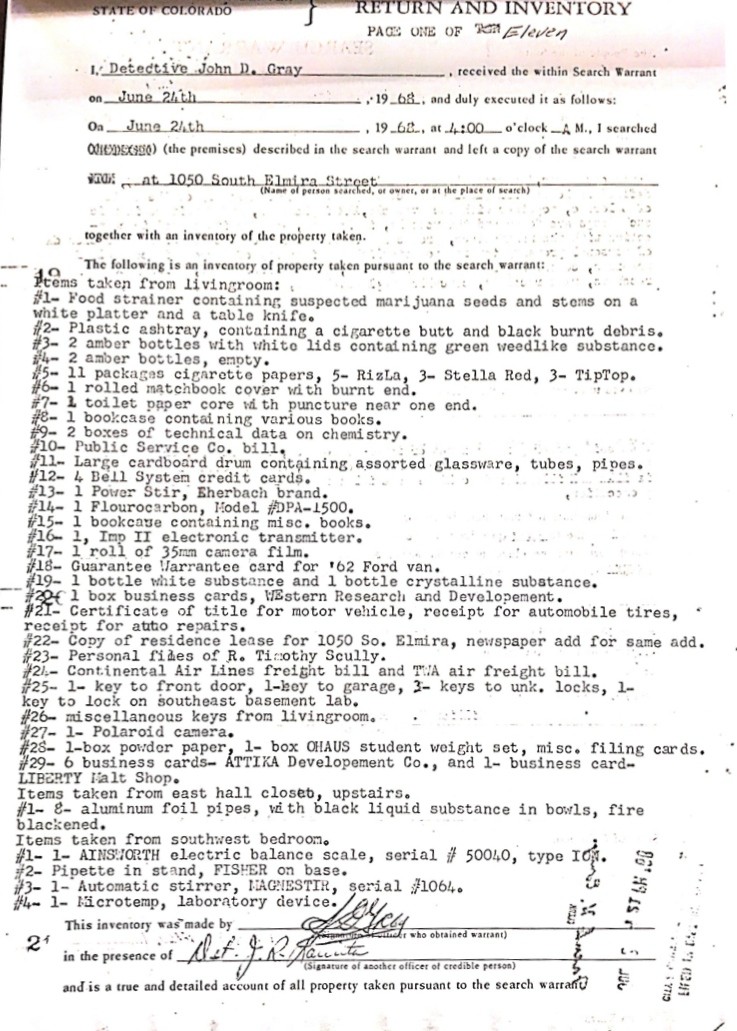

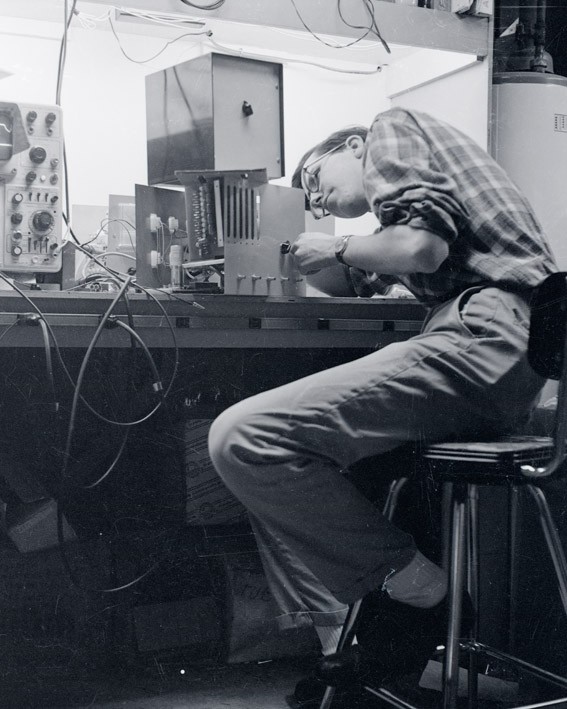

At age nineteen, Tim Scully, seen here calibrating equipment in 1964, was already skilled at electronics work.

Donald Douglas

After about an hour, he felt a tingling, euphoric sensation wash over him. Suddenly, patterns in the carpet came to life. A clock and other objects on the mantle moved before his eyes, swaying with a cosmic current he’d never known surrounded him. When Scully closed his eyes, paisley patterns were projected onto the back of his eyelids, in bright, intense colors that he didn’t recognize.

It was as if a valve had opened in his brain, allowing him to perceive raw, sensory information from the outside world that a person normally misses.

He turned to his friend Don Douglas, wondering if he was experiencing this, too?

Scully had known Douglas since kindergarten. After a stint at San Jose State University, where he’d studied Eastern philosophy, Douglas had moved in with his childhood friend. It was Douglas who’d first turned Scully on to pot, then to written explorations of mind-altering substances by writers like Aldous Huxley — The Doors of Perception and The Island among them.

But the two really wanted to try psychedelics. Douglas had learned about LSD during a 1964 lecture at San Jose State by Richard Alpert; the Harvard psychologist had told students about his collaborations with another psychedelic pariah from Harvard, Dr. Timothy Leary. At the time, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was only beginning to enter the pop-culture lexicon, even though the substance had been around for at least a decade, albeit in a secret capacity. Back in the 1950s, the United States intelligence community had caught wind that powerful, mind-altering substances were being produced by the Soviet Union. Fearing that countries behind the Iron Curtain were making LSD to use as a tactical weapon to incapacitate enemy soldiers in the field, the U.S. government funded research by the Eli Lilly Company, which produced LSD on an industrial scale and developed multiple manufacturing patents. Vague details on those patent documents would later allow enterprising citizens to figure out the chemistry behind LSD production.

As the acid took hold, Douglas confirmed that he was in just as deep as his friend. “It was like the universe with the lights turned on,” Douglas remembers."I knew I was going to have to break some laws and do things that weren't right for this higher cause."

tweet this

The two spent much of the night sitting in front of the fireplace, slowly feeding logs into dancing flames. They only spoke occasionally, but both had an overwhelming sensation that there was a common consciousness shared by everyone on earth, an inexplicable, intense feeling of oneness that bonded everyone together.

Scully had no doubt: Taking acid was the most important thing he’d ever done.

The young man had never been particularly spiritual, especially when it came to organized religion. As he was growing up, he’d viewed the arbitrary distinctions between his mom’s Protestant leanings and dad’s Catholicism as canceling each other out. Instead, Scully thrived on science. Awkward and bookish in elementary school, he was called “mad scientist” by kids on the playground. As he grew older, teasing turned to contempt for a “know-it-all.” Friends were few, and relationships with the opposite sex were a foreign concept.

“I think I have a touch of Asperger’s, although no one’s ever formally diagnosed me,” Scully says.

Yet there was no denying he was brilliant.

During high school, Scully persuaded administrators to give him a spare classroom where he could build a linear accelerator designed to bombard mercury with neutrons. It was scientific alchemy; he hoped to cause a specific isotope of mercury to capture a neutron and turn into gold. “Then the school realized that the accelerator was going to produce radiation, and parents and students freaked out and encouraged me to go to a university,” Scully recalls with a laugh. His transfer to the University of California, Berkeley was approved while he was still a junior in high school.

But despite Scully’s academic rise, he felt unsettled and directionless. The world appeared to be unraveling around him. His dad, who worked for the military, terrified him with stories about nuclear winters; his father’s job called for using Bay Area weather forecasts to figure out where nuclear fallout would go in the event of a Soviet missile strike on California. At the same time, President Lyndon Johnson was sending more and more troops and bombs into Vietnam.

Scully’s LSD trip didn’t just expose him to another realm of existence, it gave him a mission. As he later wrote: “I saw the world as a place where most people lived lives of quiet desperation, working in jobs they hated to earn rewards that turned out to be tasteless and unsatisfying. Hypocrisy and hatred, double-dealing and cheating seemed to be the way of life in the business world. Ecologically, the world was clearly headed for disaster…. Our technological power to control (and destroy) our environment and fellow humans was increasing at an explosive rate, but our understanding of ourselves, our relationships to each other and the universe around us, was not…. This was the gap that I believed psychedelics could help close.”

Douglas had similar thoughts. As the two came down from their LSD trip, they determined that they would find a way to make as much LSD as possible and give it all away, for free, to whoever wanted it. They were going to save the world with psychedelics.

They had no illusions that this task would be easy. While LSD was still legal in 1965, Scully figured it wouldn’t remain so forever. “I knew I was going to have to break some laws and do things that weren’t right for this higher cause,” he explains. “It was that sense of breaking eggs to make omelets.”"Then the school realized that the accelerator was going to produce radiation, and parents and students freaked out."

tweet this

Scully had a basic understanding of organic chemistry, but knew he needed to learn more in order to produce high-quality acid. The bookshelves at UC Berkeley’s library provided a good start, but his real break would come though meeting an LSD legend, the man who’d created the first acid he’d taken.

The introduction came through one of Scully’s other roommates, Diana Nason. She’d met Augustus Owsley Stanley III at a party thrown by Ken Kesey, the eclectic writer of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, who was hanging with a group of psychedelic evangelists who called themselves the Merry Pranksters. The Pranksters didn’t believe in privacy and had taken off all the doors leading into bedrooms and bathrooms in Kesey’s house. But Nason and Stanley managed to find a closet that still had a door, and that’s where they got to know each other.

Not long after, Stanley came calling at Scully’s house in Berkeley. He’d learned some intriguing information from Nason. “She’d told him that she had this landlord with a crazy idea of wanting to turn the world on to LSD, and he was looking for lysergic acid,” recalls Scully.

Stanley was rather impressed by Scully’s earnestness, but told him he was taking a break from LSD production. All he could focus on at the moment was a band he’d heard at a Merry Pranksters event: the Grateful Dead. “He’d had the experience of psychically linking up with them,” says Scully.

Skilled at electronics work, Stanley was offered a job as the Grateful Dead’s sound engineer, which he accepted. Soon after, he and his principal romantic partner, Melissa Cargill, invited Scully to their home to take LSD and meet these Grateful Dead guys. It was a fun acid trip. Stanley brought out acoustic ceiling tiles and had everyone paint bright paisley patterns on the tiles that he could glue overhead to create a psychedelic ceiling. “It was a nice and relaxing way to get to know the bandmembers,” Scully says. He was especially drawn to the friendliness of Jerry Garcia.

“And so I agreed to go on the road with Owsley and the Grateful Dead,” Scully continues. “I looked at it as an extended job interview for what I really wanted to do: work in [Stanley’s] LSD lab.”

By February 1966, Scully and Douglas had become roadies. They followed the Grateful Dead to Los Angeles, where Stanley rented a place in Watts that became known as the “Pink House”: a three-story pink-stucco mansion that had previously been used by a religious sect and contained built-in confessionals.

Living there was like joining a circus, Scully says. It was all an adventure for the shy, awkward introvert. Prior to meeting the band, he’d been a virgin — but that was a tough status to maintain when you were hanging around the Grateful Dead and dropping acid once a week. Scully soon began advocating free love. He took a woman named Donna to the Pink House, and after she slept with Scully, she made her way through most of the bandmembers. That was perfectly fine with Scully...until he and everyone else in the house got the clap. “I ended up paying the doctor bills because I was the one who brought her into the house,” Scully recalls.

Douglas, meanwhile, developed a reputation for being able to drive the band’s sixteen-foot GMC truck through Los Angeles while high on 600 micrograms of acid. (A typical dose is 100 to 200 micrograms.)

Primarily, though, the young men focused on pleasing their mentor, Stanley. He was a quirky fellow, full of odd notions, such as forcing everyone in the Pink House to go on an all-meat diet. He was obsessed with perfecting the Grateful Dead’s live sound and spent weeks buying hi-fi audio equipment, experimenting with large PA speakers, and rewiring gear to use low-impedence signals to reduce feedback. An autodidact, when Stanley became interested in something, he’d find out everything he could about the subject, often giving lectures to whoever was within earshot, whether they wanted them or not. And what increasingly interested him were “acid tests” — large social gatherings where the Merry Pranksters would dose everyone with psychedelics, often with the Grateful Dead providing the entertainment.

"And so I agreed to go on the road with Owsley and the Grateful Dead and help them with their acid tests."

tweet this

Scully and Douglas were on hand to witness one of the more infamous of these, the Watts Acid Test, which took place in a warehouse in South Los Angeles on February 12, 1966.

While most of their experiences with LSD had been positive, they remember becoming concerned as they watched Stanley pour liquid LSD into one of several garbage cans full of Kool-Aid. The garbage cans had no signs on them indicating that they were “electric” — meaning that they contained LSD — and Douglas watched a family with kids come in off the street and naively consume some of the Kool-Aid.

“It became apparent that there were people freaking out,” remembers Scully. “And the iconic freakout was the ‘Who Cares Girl.’”

In the middle of the warehouse, a woman began screaming, “Who cares?! Who cares?! Who cares?!”

Rather than comfort her — or care — some of the Pranksters shoved a microphone into her face.

“Don and I agreed that that was deeply unethical. That was like raping people,” recalls Scully. At that point, he realized he might need to clarify his mission somewhat: A person needed to be a stable vessel and voluntarily agree to take LSD in order to have a positive outcome; you couldn’t just give it to unsuspecting people.

But at the same time, the acid tests could be transcendent.

“There was a phenomenon that happened at acid tests — when things went well — where many of the people who were high would mentally link up to form a single additional entity, like an additional consciousness,” explains Scully. “I believe that a lot of people who became Deadheads were people who linked up with the band, and they had that psychic connection and wanted to experience it again and again. There was something magical about it, no doubt about it.”

By July 1966, Stanley needed more money to continue facilitating such far-out experiences. To raise capital, he decided to set up another LSD lab. He still had many of the necessary chemicals in storage — which was fortunate, as those chemicals were becoming increasingly difficult to buy, especially the main component of LSD, lysergic acid.

This was the moment that Scully and Douglas had been waiting for. As it turned out, Stanley had been monitoring how well they handled certain tasks while high on acid, and they passed his test: Stanley determined that Scully and Douglas could be his lab assistants, at a salary of $500 a week.

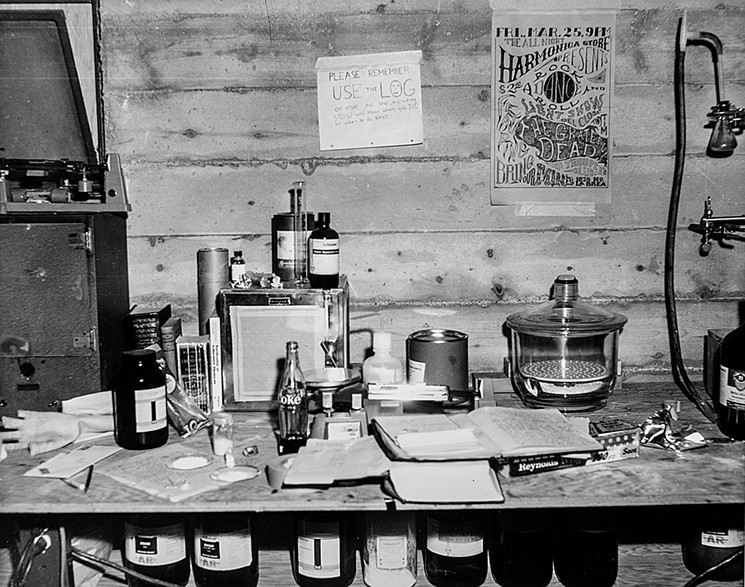

Another crime-scene photo from the Denver lab in 1968, which shows a Grateful Dead concert poster taped to the wall.

Courtesy of Jim Laurita

LSD manufacturing also involves a lot of solvent stripping — boiling off unwanted chemicals such as methanol and chloroform. A naive chemist would use heat to strip solvents, but Stanley figured out that heat caused LSD to decompose. So he employed glass contraptions known as vacuum flash evaporators to reduce the pressure on the chemicals, which in turn lowered their boiling points. In some cases, he was boiling chemicals at the temperature of cold tap water. Stanley also devised a “recycling loop” after discovering that each conversion of lysergic acid produced 88 percent "normal LSD" — what was desired — and 12 percent undesirable, "iso-LSD." By running the loop over and over, he could convert almost all of his lysergic acid into pure LSD.

Scully soaked up all the information he could. Once production was under way, he quickly learned that running an LSD lab was a 24/7 operation, since so many processes needed to happen simultaneously. To handle the demands, the team worked in shifts. “I was able to step in and handle parts of the process while [Stanley] and Melissa were sleeping,” says Scully. “And Don would get groceries and dry ice and so on.”

Another thing Scully learned: It was impossible to avoid getting high while making LSD.

“Once you start making acid, unless you take extraordinary measures, which we never did, then you’re going to get high,” he says. “It tends to get in the air and on your clothes. But what happens is that you rapidly build up a tolerance. So you’re not hallucinating violently. You’re not even that aware that you’re in an altered state unless you talk to someone who’s not in the lab. But there was definitely an electric feeling. There was a sense that we were doing something to change the world in a positive way.”

Douglas had a name for this constant exposure to LSD: “Acid Makers’ Queasy.”"It became apparent that there were people freaking out. And the iconic freakout was the 'Who Cares Girl.'"

tweet this

By the time they’d processed all of the raw lysergic acid, Stanley and his apprentices had 100 grams of pure LSD, or nearly 360,000 individual doses at the strength Stanley preferred them. That left just one final step: divvying up the product.

Stanley decided to switch his delivery method from that of previous batches. Rather than pack LSD in a powder formula inside capsules, which could result in inconsistent doses depending on how tightly the powder was packed, Stanley bought a tableting machine, which compressed carefully diluted LSD powder into a pill-like form with consistent strengths. And it was all legal, more or less.

In October 1966, the Los Angeles Times ran a story about Stanley under the headline “‘Mr. LSD’ Makes Million Without Breaking the Law.”

“What kind of man is he?” the article asked. “By reputation, he is a drifter, a dapper ladies’ man and a professional student. One of his two ex-wives calls him ‘just a little boy afraid to grow up — a Peter Pan.’”

But suddenly the legal landscape changed. That month, California became the first state to declare LSD illegal, and it became nearly impossible to obtain lysergic acid. Federal agents also began monitoring orders for other chemicals that went into LSD. That’s what brought Scully to the feds’ attention on December 8, 1966, when he drove his green GMC truck to Nurnberg Chemical to pick up supplies. As he’d find out years later in court testimony, the stock boy who helped load his truck that day was actually an undercover drug agent named Orve Hendrix.

Scully and Douglas soon noticed that they were being trailed all over the Bay Area. The feds weren’t exactly hard to spot; they tended to pair up in unmarked cars, with one agent driving and the other manning a radio. In sections of town with gridded streets, they’d employ multiple cars, with one driving north-south and another east-west.

But it quickly became apparent that the agents weren’t going to pull over Scully or Douglas; they were hoping to follow them back to a laboratory.

Losing the agents became a constant dance. Scully and Douglas started employing counter-surveillance techniques: jotting down license-plate numbers, driving on side streets and, most important of all, never going to a lab or tableting facility unless they were certain they weren’t being followed.

Nevertheless, the heat increased. Having learned Stanley’s secrets for LSD manufacturing, Scully was itching to set up another LSD lab and continue his mission of turning on the world. He realized that the best course of action might be to relocate production away from California, in a state where LSD was still legal.

He convinced Douglas to join him on an interstate scouting trip. They managed to evade the feds and travel to Seattle, where they bought a used station wagon that they used to drive east through Washington into Idaho and Wyoming. The pair had envisioned setting up a lab in an extremely rural, isolated location, but they realized that wouldn’t work for two reasons.

"Denver felt really good. It was a beautiful city, and we saw lots of houses had basements, which we also liked."

tweet this

“In Wyoming, we learned that cowboys don’t like hippies. We stuck out like sore thumbs,” says Scully.

The other reason? To run certain processes in the lab, they’d need plentiful supplies of dry ice — which were only available in big cities. So Douglas and Scully turned south, setting their sights on Denver.

The moment they arrived in Colorado’s capital in mid-December 1966, they knew they’d found their spot. While the Mile High City was seeing increasing numbers of young vagabonds around lower downtown and the railyards, some of whom formed communes in abandoned buildings, Scully and Douglas wanted to keep a distance from their most likely clients. Instead, they were drawn to quieter areas. “Denver felt really good,” recalls Scully. “It was a beautiful city, and when we were driving around near City Park, we saw that lots of houses had basements, which we also liked.”

After flipping through advertisements in the Denver Post, the pair signed a lease for a house at East 26th Avenue and Ash Street. Using false names, they told the leasing agent that they would be conducting scientific work in the basement as part of a river-flow testing project for the Bureau of Reclamation.

Lab location secured, the two still faced the daunting task of moving their lab equipment from California to Denver without attracting the attention of federal agents.

Sure enough, no sooner had they loaded a van full of equipment than they spotted a car with federal agents hot on their tail. But Douglas had a plan: He knew of an intersection in the Bay Area with a short stoplight cycle and heavy cross traffic, and figured he could lose the tail if he timed things just right. So he drove up to the intersection, agents right behind, then floored it as the light turned from yellow to red. The agents were stuck at the light.

Scully was elated: They’d successfully evaded their pursuers. In fact, even though he and various associates would make numerous trips between California and Colorado, they were never followed to Denver.

Crime-scene photos taken by Denver police detectives show vacuum flash evaporators in the basement at 1050 South Elmira Street.

Courtesy of Jim Laurita

Although Stanley had provided the funds for the lab, he stalled. He wanted Scully to produce another psychedelic that was still legal at the time — STP, which some said stood for “Serenity, Tranquility and Peace” — before he’d agree to bring lysergic acid out to Colorado for another batch of LSD.

Scully was no fan of STP, having had a negative trip during which he hallucinated that he was trapped in a war zone. But he was willing to jump through that hoop while Stanley and Cargill collected their last lysergic acid from a safe-deposit box in Phoenix. That took a while, since Cargill had either forgotten the name of the bank or the name on her account; she finally found the box in May 1967.

Making LSD in Denver was very similar to making LSD at the Point Richmond lab. Acid Makers’ Queasy kept everyone wired and focused, but Scully was just as high on the idea that they were pumping out a miracle substance that would save the world. With Stanley and Cargill’s help, he and Douglas had converted all the lysergic acid into pure LSD by early September. The output this time was even larger than before: 300 grams, or about a million doses of LSD.

Stanley and Scully took the acid back to California for tableting. As always, the heat was on as soon as Stanley or anyone associated with him showed their faces in the Bay Area.

It was getting to be too much for Douglas. In a private meeting with Scully and Stanley, he begged them to take a hiatus. They could still pursue their mission, he said, but they should work normal jobs for a while until the feds grew bored of watching them. Then they could resume manufacturing LSD without so much pressure.

Scully and Stanley refused to slow things down.

“I’m out, then,” Douglas remembers telling them. “And I’m not just out for the next lab. I mean I’m out.”

As it turned out, Douglas made his exit just before things started going downhill.

On December 20, 1967, Scully noticed that there were ten times as many federal agents milling around his house in Berkeley as usual. He called Stanley, warning that his tableting facility might be compromised. Sure enough, it was busted the next morning, and 67 grams of LSD that had come from the Denver lab were confiscated. Stanley was arrested.

Although he made bail, the bust initiated a long, drawn-out legal process that would consume him for years. That’s when Stanley decided to turn his back on acid production for good, focusing exclusively on doing sound work for the Grateful Dead.

With his mentor out of the LSD game, Scully was on his own, which meant he had to go further afield for financing and chemicals. In order to find some of the latter, especially lysergic acid, he started making trips to Europe with another psychedelic missionary named Nick Sand. Theirs was a marriage of convenience: Although Sand professed to have the same zeal for LSD, their personalities were polar opposites. “I got the impression that he was an adrenaline junkie of sorts,” recalls Scully. “He was much more into taking risks.” And that included hiring drug smugglers to transport various chemicals through way stations like Montreal.

While Sand took over tableting operations in California, Scully decided to set up a second lab in Denver. Now that Douglas was out, he recruited his then-girlfriend, Ruth Pahkala, and a street hustler named Rory Condon to help him. Once again, they scanned the classifieds and located an ideal house, this one at 1050 South Elmira Street, just blocks from Aurora. On February 26, 1968, Condon signed a lease under the alias “John R. Roberts,” claiming he was a representative of “Western Research and Development.”

The trio remodeled the basement of the rental house, occasionally using the lab equipment for side projects like making DMT or cannabis extracts, while Scully worked to secure the chemicals needed for LSD. In June, after he left on another scouting trip to Europe, Pahkala and Condon decided to kill time in California. As they left the Denver lab, they noticed that the water spigots outside the house weren’t working — a pump inside a well on the property had broken — but they figured that repairs could wait until they returned.

In his lab, Tim Scully kept running notes. This notebook, from the first Denver lab, shows Scully's notes about making STP.

Courtesy of Jim Laurita

Today, Scully believes that if Pahkala and Condon had followed his instructions and flown back that night, they would have been there to greet Chance, who would never have discovered the smell — and the police would not have been called in. (Scully thinks the odor could have come from spilled dimethylamine — one of the chemical components of DMT — though he has no idea how the spill might have occurred in the usually immaculate lab.)

But Condon and Pahkala did not fly back to Denver. Scully discovered that when he called the laboratory two days later, on June 24, and got a strange voice on the other end of the line.

“Scully residence,” the voice said.

The real Scully hung up immediately. He knew that the lab had been busted, since the property hadn’t been rented in his name.

Two days later, his lab assistants finally arrived at the house. As Condon pulled up, he noticed an unmarked van parked on the street. Pahkala, sensing something was off, told him, “No, don’t stop!” But Condon went ahead and pulled into the driveway.

As they entered the house, they were surprised to hear Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues” playing on the basement hi-fi.

Detective John Gray, who happened to be inside the home inventorying items, was alerted that two strangers had just walked through the front door. After identifying himself, the detective asked Condon, “Do you live here?”

“Yes.”

“What’s your name?”

“Rory Condon.”

Gray then turned to the woman and asked the same.

“Ruth Pahkala,” she answered meekly.

Gray recognized the names from letters and journals he’d collected around the house, and he placed the pair in handcuffs right away.

By the time Scully learned what had happened from his lawyer, Al Matthews, he realized that he’d made some grave errors himself. While he was traveling in Europe, he’d missed the news that Colorado had made LSD illegal in early 1968. This state’s law was even stricter than California’s, with LSD production a felony punishable by up to fourteen years in prison compared to California’s five.

Freaking out, Scully shacked up in a cabin near Eureka, California, where he could collect his thoughts. As part of that process, he wrote a list of all the things he wouldn’t be able to do if he decided to live the rest of his life as a fugitive. It included things like using his real name, visiting close friends or relatives, and subscribing to his favorite magazines (even under an alias), because it could give away his location. “I made a longer and longer list of things that I couldn’t do, and finally came to the conclusion that being a fugitive wasn’t for me,” he recalls.

Still, he elected not to turn himself in after he had his lawyer check to see if there was a warrant out for his arrest in Colorado. Matthews didn’t find one (but only because the warrant was sealed under a grand jury indictment).

Assuming that he still had time, Scully decided to set up another LSD laboratory to raise money for Pakhala and Condon’s bail and legal defense. He’d lost his glassware during the bust but still had most of the raw chemicals — “the hard stuff to get,” as he puts it today — in California. He also had an eager partner in Sand, who’d been doing tableting work and hounding Scully to teach him the secrets behind LSD manufacturing. Together they set up a lab in Windsor, California, where they made what would become the most famous acid of all time. They called it Orange Sunshine.

The little orange pills were distributed through a network of ragtag bohemians called the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. The sales generated a significant income — enough for Scully to get Condon and Pahkala out of jail and cover their legal costs.

The money that was left over would later go toward Scully’s own defense.

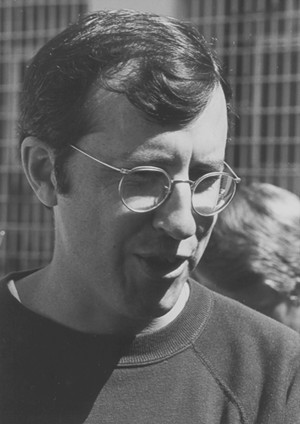

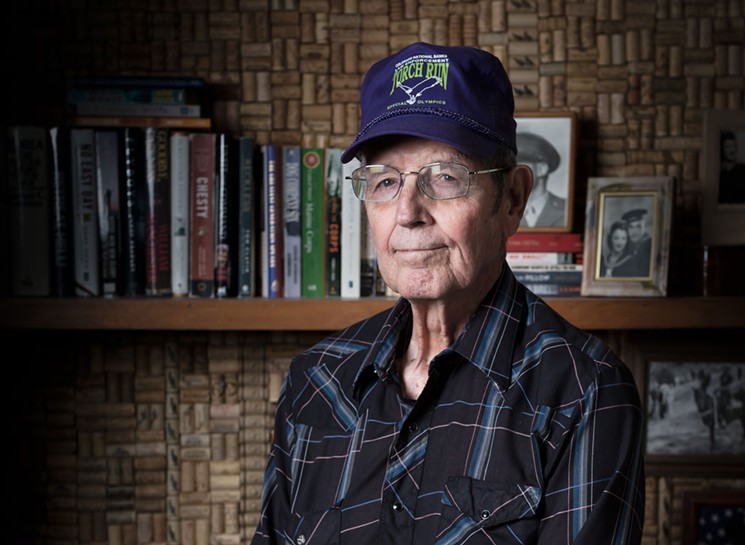

Retired Denver Police detective John Gray believes that the LSD laboratory on South Elmira Street was the largest he ever busted.

Jake Holschuh

“There was no doubt about who was there in the house,” says Laurita today. “It was the most elaborate lab I ever saw in Denver.”

The prosecution, led by a passionate deputy district attorney named Irving Ettenberg, was also getting a boost from the federal government, which was providing expert witnesses, including a chemist with the Food and Drug Administration. “We felt good about the trial throughout. We had ample evidence, and it impressed the jury,” remembers Laurita. The two were convicted.

Laurita and Gray were even more ecstatic when Scully was arrested, on May 26, 1969, at an airfield in California, where he was having work done on a plane he owned. He faced a possible sentence of 56 years in prison with four felony charges (fourteen years for each charge) stemming from the Denver lab.

Through the late ’60s, Laurita and Gray were the DPD’s main weapon against psychedelics, which they considered a growing and existential threat. “They were a danger. No one could say that there weren’t any permanent ramifications when someone used or abused them,” says Laurita, who today works as a private eye. “Parents would come in with their children whacked out, and you’d sit there and wonder what the future is for them.”

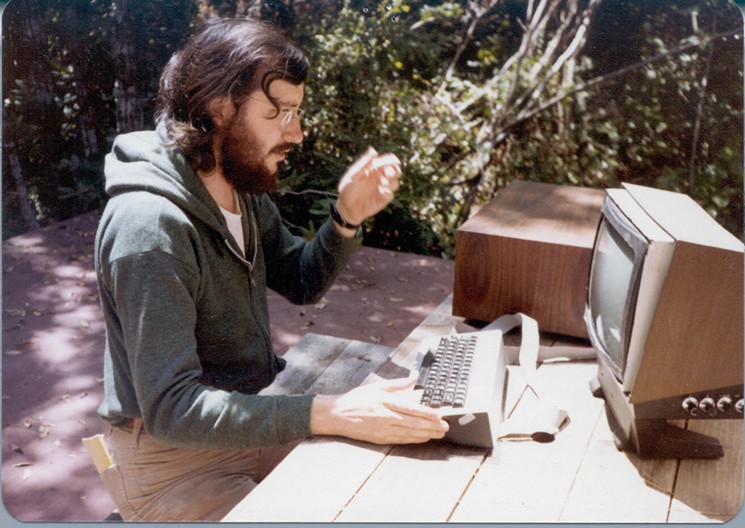

Retired Denver Police detective Jim Laurita is still frustrated over the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to overturn convictions against the laboratory participants.

Jake Holschuh

But the detectives’ satisfaction over the South Elmira drug bust wouldn’t last.

Scully, Pahkala and Condon all appealed their cases, based on a Denver ordinance that their lawyer found stipulating that even in the case of a suspected dead body, a search warrant was necessary to enter a property without a tenant’s permission. The Colorado Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal, and in October 1971 determined that the Denver police had conducted an illegal search of the property at 1050 South Elmira.

“To this day, I can’t figure out what the Supreme Court was thinking,” complains Gray. “We were really frustrated — and so ticked off that we had to give them back all that stuff to make LSD.”

He points out that the responding officers had the owner’s permission to enter the property, and even if a dead body doesn’t require medical attention, that doesn’t mean there isn’t someone alive inside who might need help.

“It was jarring from the standpoint that there was no common sense applied in the appeal process,” Laurita adds.

Scully calls the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision “my one free trial.” Throughout the Denver court proceedings, he was out on bond, traveling back and forth between Colorado and California, where the feds were still pursuing him because of his production of Orange Sunshine. They were getting better at tracking him; there were times he couldn’t lose the tail. He spilled LSD on his skin in a lab accident and began hallucinating that federal agents were camped out in trees, watching his every move. But the feds weren’t the only reason he was ready to turn away from psychedelics. “The psychedelic scene was getting darker and darker by 1969,” he explains. “There were fewer smiling faces on the street and more people who looked like they were strung out on hard drugs.”

While he was giving up his original mission, Scully was excited about another, legal outlet: designing “biofeedback” instruments that measured brain waves and muscle contractions.

But he couldn’t escape his past. A federal task force investigated an accountant that Sand and Scully had shared, as well as the financial records of their wealthy friend Billy Hitchcock, who had financed many of the acid labs after Stanley backed out of LSD production in 1967. In April 1973, Sand and Scully were indicted by a federal grand jury and charged with income-tax evasion and conspiracy to produce and distribute LSD.

During their trial, which began in October that year, they drew the ire of Judge Samuel Conti when they lied on the stand, saying they’d been trying to make a close relative of LSD: ALD-52, which was still legal. They even had a friend make some ALD-52, then pretend to have dug it up from an old stash that Scully and Sand had “buried.” The tablets were ready just before Scully took the witness stand, so he didn’t have a chance to try them ahead of time.

When the government’s chemist tested the substance, it presented as LSD.

“That’s when we learned, boys and girls, that ALD-52 is very unstable and will decompose into LSD at the blink of an eye,” says Scully, who adds that he regrets lying to the judge.

Scully was sentenced to twenty years in federal prison, and Sand received fifteen years.

They wound up sharing a cell. Although their personalities still grated, both appreciated that they hadn’t testified against each other.

McNeil Island Prison was a maximum-security penitentiary in Washington state where people with long federal sentences were sent. Many of them had violent pasts, including an Eskimo who’d eaten his family. Sometimes inmates would detach the metal handle from mop buckets and beat rivals to death with them. “There’s someone getting piped,” Scully would think when he heard screaming at night.

But Scully’s time at McNeil Island was remarkably short. Just before he entered the prison, his reporting officer had introduced him to Robin Wright, a woman who had cerebral palsy and a difficult time communicating, since she could only control motion in one of her knees. Drawing on his expertise with electronics, Scully saw that he could design a button-and-computer program — sort of an early version of autocorrect spelling on smartphones — that would allow Wright to communicate much more efficiently.

Wright’s family believed in Scully; they raised money to buy computer parts and lobbied the prison to allow him to work on the device. Not only did Scully ultimately build the computer for Wright, but he also designed a new computerized inventory system for federal prisons.

With the recommendation of the warden, Scully’s sentence was dropped from twenty to ten years. Then, against Judge Conti’s wishes, Scully was given an early parole hearing. The judge offered a furious statement for the record: “I have been involved in the law for thirty years, and I have never in my life seen any case that was so damaging to society as this case was. A man who was intelligent — I knew he was intelligent, everybody knows he was intelligent — but that doesn’t mean, because he is intelligent, we are now going to give him the congressional medal of honor, which apparently he is one step from receiving. He may be the outstanding man of the year in your book, but he is not the outstanding man of the year in my book.”

Scully was released from prison on May 29, 1979. He’d spent just three and a half years behind bars.

In the nearly four decades since then, Scully has been successful in a variety of fields, including computer programming and making biofeedback instruments. Although he says he hasn’t touched LSD in all that time, he can’t escape his reputation as a psychedelic revolutionary. LSD enthusiasts sometimes reach out to him, occasionally asking chemistry advice, which Scully refuses to give.

In response to the continued interest, though, in the 1990s Scully began compiling an extensive record on psychedelics, which he calls the “History of Underground LSD Manufacturing.” He’s located and scanned over 50,000 pages of primary-source documents, including court transcripts and newspaper articles, and has over 13,000 entries in a computerized file directory detailing specific labs, busts, agents and more involved in the psychedelic movement. He plans to eventually donate the project to a university, but is currently using his research to write a narrative memoir with the working title Trying to Save the World.

Scully has also been featured in documentaries — most recently, The Sunshine Makers, which was released in 2016 and focuses on his and Sand’s strange but fruitful relationship.

Unlike Scully, Sand went on to make more LSD. While released on an appeal bond in 1976, he went on the lam in Canada and India, producing more psychedelics, until he was caught in 1996. He passed away on April 24 of this year, at the age of 75.

Today, Scully has conflicting feelings about psychedelics and the role he played in their proliferation. Over the years, he’s corresponded with people who were never the same after bad acid trips. “That’s hard,” he says. “It’s clear that as much good as we were trying to do, we also managed to do some harm.”

He now believes that his illegal production of LSD hindered valuable studies, including ways it might be used to help people with conditions like PTSD or autism. “We bear a significant responsibility for setting the research back forty years or more,” Scully says. That research is just beginning again, spurred in part by growing trends like microdosing — taking regular, small amounts of LSD.

In retrospect, he sees that his original mission of spreading LSD around the globe was deeply flawed."It's clear that as much good as we were trying to do, we also managed to do some harm."

tweet this

“The bad thing about scattering it to the four winds the way that we did is that there was no control to keep people who shouldn’t be given LSD access to it, like very young children, adolescents and teenagers,” Scully explains. “With hindsight, if we get to the point — and I hope we do — where people can legally take LSD for spiritual exploration, I think that it should be treated at least as carefully as liquor is. People should be adults before they have access to it. Their egos should be fully formed, their brains mature enough, so that you’re not dissolving your ego to [the point that you’re not] able to recover in a safe way.”

But Cosmo Fielding, director of The Sunshine Makers, thinks that Scully is being too hard on himself. “I don’t think he should take any personal blame, because if it wasn’t him who was going to be making LSD, it was someone else,” Fielding says. “Tim did his best to keep it out of the criminal underworld...and keep it as a spiritual tool for growth and enlightenment.”

In fact, Fielding believes that the activities of Sand and Scully, including the Denver labs, played a positive role. “They were fueling the global psychedelic revolution, and if you look at the impact that the widespread psychedelic use of that period had on society, it’s profound,” he says.

“Before the 1960s, no one had long hair, no one had sex before marriage, no one knew who the Dalai Lama was, if you were a vegetarian you were a complete freak, no one knew what yoga was... and so all of these things that we take for granted, including freedoms and expressions and things that enrich one’s life today, were all represented from the hard-fought battles by these guys. And Nick and Tim were right at the center of that movement. They produced the most widely distributed and highest-quality psychedelics of the psychedelic revolution.”