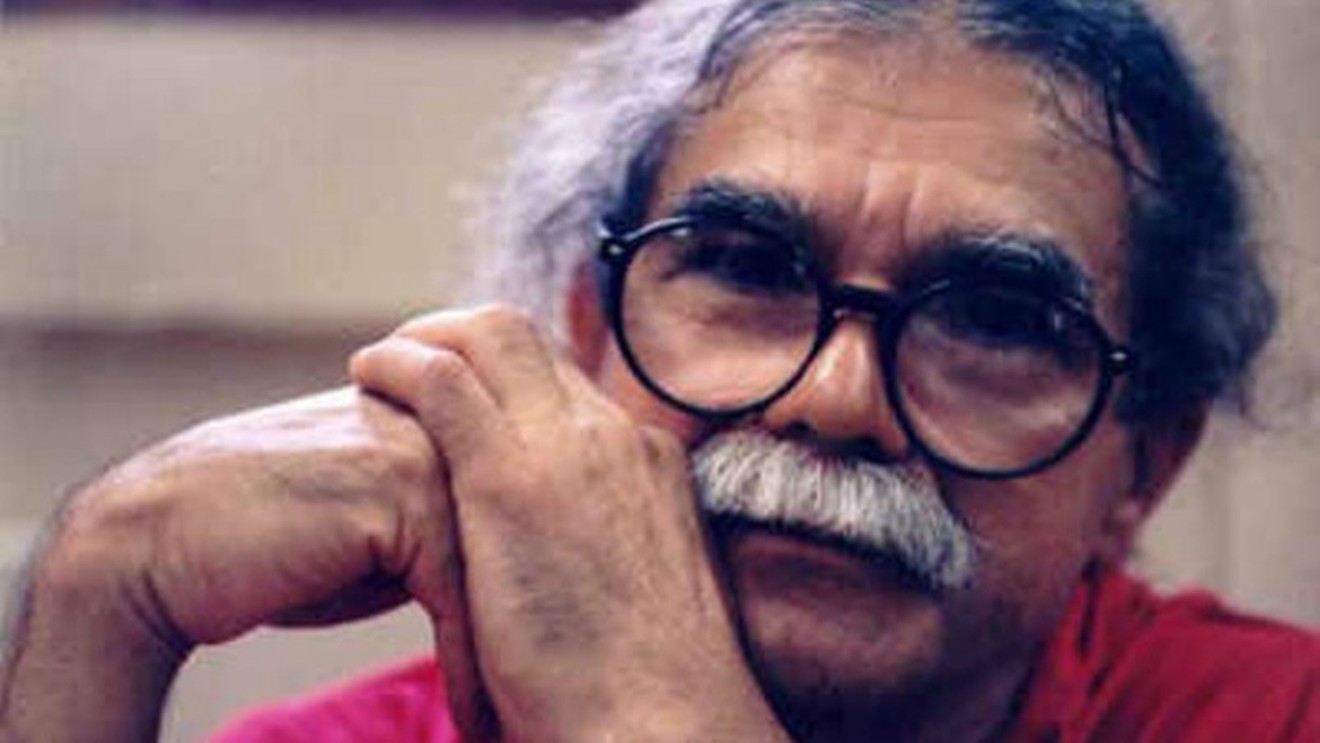

President Barack Obama's decision this week, in the waning days of his administration, to commute the seventy-year sentence of Puerto Rican radical activist Oscar Lopez Rivera has been greeted with celebration in some quarters and outrage in others. But if nothing else, the move solves a problem the American justice system has been unable to crack for the past 35 years: What do you do with a self-proclaimed "prisoner of war" in a country that claims to have no political prisoners?

Critics of the commutation point out that Lopez Rivera was one of the reputed leaders of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN), a Puerto Rican independence group linked to more than a hundred bombings and five deaths in the ’70s. At the time of his 1981 conviction on weapons and seditious conspiracy charges, he was considered among the principal architects of a campaign of terror and armed robberies by ultra-nationalists that was supposed to spark a revolution and transform Puerto Rico into a socialist state.

Lopez Rivera's supporters point out that no court ever established his direct culpability in any of the deaths or other violent crimes, yet he's already served more time than many murderers, as well as all of his alleged co-conspirators. He rejected a conditional clemency offer from President Bill Clinton decades ago, though the reasons for that rejection vary in different news reports. (He refused to renounce terrorism; one of his co-defendants, who was finally released in 2010, wasn't offered the same deal; the deal didn't include the additional fifteen years tacked onto his sentence for a prison escape attempt that he has always maintained was a setup.)

Lopez Rivera has never confirmed or denied his role in the FALN. At the same time, he admits that his experiences in Vietnam and as a community organizer in Chicago drew him to the Puerto Rican independence movement, and he has defended his right, "as a colonial subject," to attempt to overthrow United States rule over his native island. And there's no question that he's been treated differently in the federal prison system than other inmates whose crimes weren't so politically charged.

More than twenty years ago, I met Lopez Rivera shortly after he arrived at the U.S. Penitentiary Administrative Maximum in Florence. He was one of the first tenants of the new supermax, despite a record of generally good behavior (minus the alleged escape attempts) at other prisons. In an interview with Westword conducted in a glass-shielded booth, he explained how his decision to declare himself a prisoner of war, one who didn't recognize the authority of the officials who put him on trial, sealed his fate: "When we go to trial, we don't defend ourselves," he explained. "So, automatically, we get the maximum sentence on every charge we face."

Although he refused to work for the federal prison industry, UNICOR, because of its contracts with the military, Lopez Rivera made it through the three-year program at ADX in only 23 months, becoming one of its first graduates. His "reward" for his exemplary record was to be shipped back to the penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, where he had even fewer privileges than he'd had at ADX. His supporters maintain that his top-security status during his many years of incarceration, including his stints in lockdown at ADX and Marion, had far more to do with the political nature of his charges than whether he posed a serious escape risk or a danger to staff.

Releasing Rivera, who just turned 74, long after the FALN has faded into the dustbin of history will doubtless still stir controversy. But Obama is showing some boldness in his finals days in office, offering more commutations and pardons than any of his predecessors, including a wave of releases for drug offenders serving overkill sentences.

It's too bad that no governor of Colorado has shown similar internal fortitude in using the power of clemency to correct disproportionate (or just wrongheaded) sentences on a local level — such as in the cases of Charles Farrar, Donny Andrews, Krystal Voss, Eric Lightner and brothers Brian and William Lee, and other manifestly unjust sentences we've written about over the years. The protracted punishment of people who may well not have committed the crimes they were convicted of — and in Farrar's case, there's no evidence the crime even happened — costs taxpayers millions in incarceration costs and further undermines public confidence in the justice system's ability to get things right the first time around.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]