Although the University of Colorado Buffaloes aren't going to a college-football bowl game in 2017-2018, thanks to a mediocre 5-7 record, nine of its fellow members in the Pac-12 conference qualified, with eight of those contests taking place on or after December 26. If the Buffs fall short again next year, though, some of its staffers will still be busy, because CU Boulder has been chosen to coordinate an ambitious research project into traumatic brain injury among student athletes, including those who slam heads on the gridiron, with one of the main tools being EYE-SYNC, a cutting-edge device designed to diagnose concussions by way of eye movement.

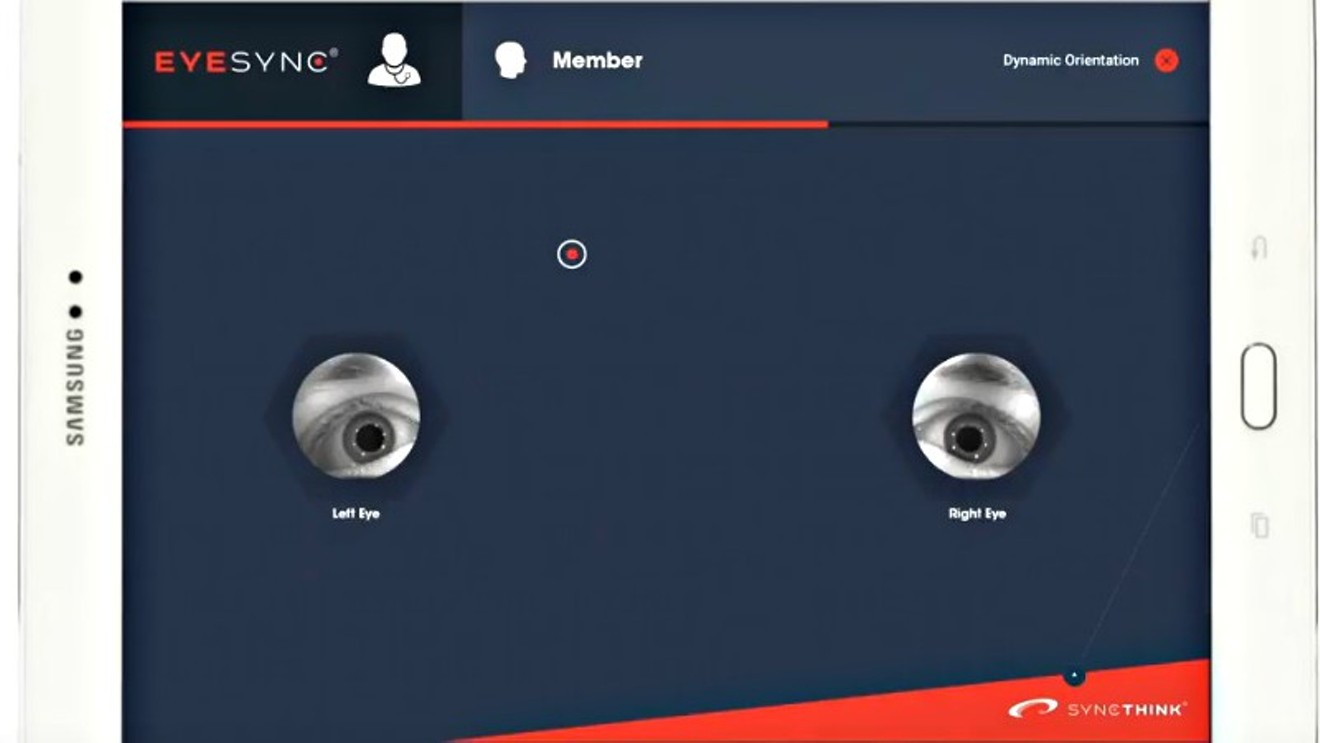

"It's essentially a VR headset that's got infrared cameras that will track the movement of the eye," says Matt McQueen, an associate professor of integrative physiology at CU who's been chosen to serve as one of the study's main research investigators. "It's a more objective measure than just asking student athletes questions."

Concussions aren't unique to footballers; those who play soccer and a range of other sports are at risk of brain injuries. However, the head-to-head contact that happens repeatedly during every minute of football action has fueled research into chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a disease defined as a "progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people with a history of repetitive brain trauma, including symptomatic concussions."

In 2015, Frontline reported that a staggering 96 percent of former NFL players whose autopsy results were examined in a Department of Veterans Affairs/Boston University study showed signs of CTE, and numerous notables who've displayed CTE symptoms have committed suicide, including Rashaan Salaam, who won the 1994 Heisman Trophy while a member of the CU Buffs.

CTE fears already appear to be causing a decrease in youth football participation, as we explored in our recent post "Will Good Parents Let Their Kid Play High School Football Anymore?" Specifically, a study by Roger Pielke Jr., director of CU Boulder's Sports Governance Center, showed that 25,000 fewer boys played high school football across the country last season than the year before, continuing a trend that shows no signs of slowing.

Hence the urgency behind what's been dubbed the Student-Athlete Health and Well-Being Concussion Coordinating Unit being coordinated by CU. "It's a multi-year effort across the entire Pac-12," McQueen notes. "We'll be looking at all aspects of incident concussion and, in particular, how student athletes are recovering from these concussions using a whole variety of assessments that will be done at very specific intervals following a concussion event."

Consistency is important, McQueen maintains, "because it gives everybody a kind of common backbone, so that we can then study these athletes to learn who's responding in different ways and if there's a common feature we can tap into for the optimal recovery process. It will establish a research focus to look at this from a scientific perspective."

The initiative "will get going before spring football," he reveals, "but it will really be ramping up over the next three years. At the end of those three years, all the Pac-12 schools will be up and running and collecting these types of data."

That includes readings generated by EYE-SYNC, developed by SyncThink, a California-based technology company. According to McQueen, "There will be stimuli in the headset — a red dot that will move around in a circle. Infrared cameras will be able to track the accuracy of the eye in terms of tracking the source of light through different movements. And ocular motor impairment is a big part of concussions."

The hard numbers generated by EYE-SYNC are key, in McQueen's view, because "even though there's heightened awareness of concussions — and that's a good thing — we're dealing with hyper-competitive individuals, big-time college athletes with lots on the line. If they're a star athlete, they want to help their team, and I think that motivation comes from a good place. But in the actual moment, they may not think they're impaired or have an issue. So as clinicians, we need tools so that we can say, 'I know you answered these questions the right way, but something doesn't seem right. I'm going to hold you out.' At some point, we have to take that side, where there's a burden of proof for them to go back on the field or the court."

What will happen if McQueen and his colleagues discover that no matter what they do, there's no way to make football safe enough to justify continued participation? "I'm an epidemiologist, a researcher," McQueen replies, "and I try to stay as much as I can out of the politics of these things as I can, and focus on the health and wellness of these athletes. So I try to think about what we can do to optimize recovery for each individual. Rule changes and legal matters are going to play themselves out in the NCAA, but there's a group of us focusing on what is happening now and making sure our student athletes here and across the Pac-12 are getting the optimal care they need to recover."

Moreover, the analysis won't end when a players' collegiate playing days are done.

"We want to follow these athletes when they graduate," McQueen says. "We want to know how they're doing in ten years, fifteen years. You've got to start somewhere with that when you get into the deeper questions about people who may go on to play in the NFL. So this is the starting point."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]