The invasion began at 8:30 p.m. and lasted until the early hours of the morning, a time when no one would notice that infiltrators had stealthily slipped through the computer’s defenses. Once inside the machine, the hackers binged on data, consuming sensitive information from around the globe.

The next morning, Kathleen Lamb checked her e-mail inbox, learned of the attack, and was immediately irritated. As a computer technician at the Colorado School of Mines, she occasionally had to deal with hacks and breaches of the university’s computers, and she now had a slew of e-mails from network administrators around the country — and even a few outside of the United States — informing her that a computer located on the Mines campus in Golden, Colorado, had been used to probe or access their networks in a suspicious manner.

Probably just some damned bored kid, too smart and with nothing better to do, Lamb thought. Mines students had occasionally hacked into one of the school’s computers before, and this attack that had started on October 7, 1996, coincided with the early days of the fall semester.

“Hey, ‘baby_doe’ is one of your machines, right?” Lamb asked her superior in the IT department, David Larue, as she entered his office, waving a sheaf of e-mails she’d received from other network administrators.

Larue checked a list of computers. Yes, he replied, there was a machine named baby_doe located inside the robotics lab in the Brown Building.

Like Lamb, he wondered if some clever student had figured out a way to take over the computer’s Unix public-domain software. Still, he needed to locate and close the security loophole, so he walked across the Mines campus, entered the robotics lab and pulled baby_doe offline.

After some sleuthing, Larue discovered a file directory deeply nested in the computer’s SunOS operating system, with rewritten files that were designed to hide the computer’s activity, record user names and passwords, and probe computers on other networks around the world for weaknesses in their security. In 1996, the early days of the Internet, networks at universities, government agencies and military departments were closely interconnected, so it was relatively easy to hopscotch between sites once a privileged computer was compromised.

In an incident report dated November 6, 1996, Larue described a log he’d found detailing the computer’s activity during the time it was taken over: During a ten-hour period on October 7 and 8, baby_doe had probed over 1,300 sites, with another 3,000 still waiting in a queue when Larue took it off the network. The list included computers at NASA, the Navy, the Air Force and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“It is of course embarrassing that sites around the world knew we had a problem before we did, so tools for monitoring and analyzing need to be put in place,” he reported, but still concluded, “All in all, we fared reasonably well.”

Larue is now retired, but he remembers the incident well. “I thought it was interesting enough to write up, but there are much more colorful stories that I could dredge up,” he says. “This had the usual salutary lessons about not letting machines get out of date and not keeping up with operating-system patches — the same kind of stuff that you hear about today.”

But today, we’re also hearing far more frightening stories about U.S. systems being compromised by hackers associated with the Russian government. And as it turns out, Russians were probably behind the invasion at the Colorado School of Mines over twenty years ago, too.

Recently declassified documents reveal that the 1996 baby_doe attack was the earliest assault in the first confirmed intergovernmental cyberwarfare campaign: a two-year-long operation carried out by Russia against the U.S. that was dubbed “Moonlight Maze.”“It is of course embarrassing that sites around the world knew we had a problem before we did.”

tweet this

And not only is the Colorado School of Mines baby_doe computer the earliest victim cited in U.S. military documents, but other Colorado targets were also hit by the Russians — including a computer at the Jefferson County Library that was compromised in 1998 and used by Russian intruders to go after U.S. military and government targets.

When the federal government realized the severity and scope of the attacks, it launched a Moonlight Maze inquiry in 1998, the largest digital forensic investigation ever conducted to that point. The counterintelligence operation ultimately involved over 100 federal agents, some of whom traveled to the doorstep of the Kremlin. Today, Moonlight Maze is regarded as the world’s first major state-on-state cyberattack, one that forever changed the digital landscape by proving that hackers could steal state secrets just as effectively as they could carry out corporate espionage and steal funds from bank accounts.

It also set the stage for events currently dominating today’s news cycle, including reports that Russians meddled in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Despite Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin downplaying (if not flat-out denying) Russia’s role — the two leaders even went as far as discussing a joint “impenetrable cybersecurity unit” when they met on July 7 at the G20 Summit in Hamburg, Germany — on January 6 the U.S. Intelligence Community, a federation of sixteen government agencies, released a report unanimously concluding that digital operatives in Russia had sought to undermine the U.S. election process and damage candidate Hillary Clinton’s chances to win the presidency through a variety of methods including hacks, leaks and the spread of fake news.

This campaign, which evolved through two decades of trial and error, had its origins in Moonlight Maze.

Thomas Rid, a professor of war studies at King’s College in London, recently uncovered many of the secrets around the early days of cyberwarfare, including the attacks against Colorado targets by Russian hackers. In June 2016, Rid released his book on the topic, Rise of the Machines: A Cybernetic History. It was the product of more than two years of interviews with former investigators, as well as discoveries in declassified documents he’d obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests.

In one Navy document, Rid found a reference to the baby_doe attack at the Colorado School of Mines. From that part of the paper trail, he was able to start piecing together the most comprehensive retelling of the Moonlight Maze investigation to date — and just how investigators had concluded that the Russian government was behind the attacks.

Until 2015, when Rid interviewed him about the baby_doe attack, David Larue knew nothing about the possible connection to Russian hackers. No federal agent had ever approached Larue about the incident, but Larue says he isn’t surprised that investigators would keep their findings secret. (The FBI declined to speak with Westword about any aspect of Moonlight Maze.)

“We were envisioning something less draconian than a state-sponsored attack,” says Larue. “So we neither had that thought, nor had we run into evidence that would lead us to that assessment.”

But the digital world was quickly evolving at the time of the baby_doe attack. Not only were more people buying personal computers and connecting to the Internet, but cyberattacks were becoming quite sophisticated.

According to Rid, hackers had already become a phenomenon by the late 1980s, with a few cases like the “Morris worm” getting mainstream media coverage. Cliff Stoll’s The Cuckoo’s Egg, published in 1989, chronicled the true story of how a hacker breached the computers at a California research laboratory and then sold stolen files to the KGB, Russia’s spy agency.

By 1993, the Pentagon had realized that cyberattacks posed a threat to national security, and was testing its own security by assigning in-house hackers — dubbed "the Red Team" — to try and breach its systems. The Red Team shocked the military establishment by taking control of 7,860 out of 8,932 of the systems it attacked, a success rate of 88 percent. It was an embarrassing sign that hackers were far outpacing their cybersecurity counterparts.

And similar attacks followed the Colorado School of Mines invasion. In December 1996, intruders broke into one of the Navy’s main command centers at NAVSEA Indian Head, in Maryland. In 1997, six different naval outposts, including the Naval Space Command and the Naval Research Laboratory, were breached. The same group of hackers was soon able to gain complete and total control of computers on networks used by the Air Force, NASA and the Environmental Protection Agency, allowing the intruders to view, modify and export any information on those machines.

As with baby_doe, many government targets were accessed through compromised computers on university campuses — Harvard, Duke, Cal Tech and the University of Texas at Austin among them. Other attacks against U.S. military and government networks were launched through proxy computers located abroad, including relay sites in the United Kingdom. By daisy-chaining compromised computers, the hackers covered their tracks and made it difficult for investigators to determine their actual origin.

In 1998, officials with the FBI, the Pentagon and the Department of Defense decided to pool their resources and create an investigative task force to track down the hackers. Doris Gardner, a computer forensics expert with the FBI, and Michael Dorsey, an information systems specialist at the Pentagon, were picked to lead the investigation, which was dubbed Moonlight Maze because the attacks mostly occurred at night and the case was complex, like a labyrinth. Over the next few months the task force grew to over a hundred agents, and even got its own working space in the Strategic Information and Operations Center on the fifth floor of FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C.

With all that expertise under one roof, the group finally got a grip on the scope of the attack. In his book, Rid cites an internal report that claimed the hackers had stolen so much information that if all those files were printed out and stacked, the paper column would be as high as the Washington Monument.

Moonlight Maze investigators suspected the attacks might be coming from Russia, in part because of the times when the hackers worked and also because several attacks had been traced to Internet service providers in Moscow, but they also acknowledged that the culprits could be working in other countries and leaving deliberately misleading clues.

Then federal agents discovered that another Colorado computer was being used by the hackers as a proxy site to access military and government networks around the U.S., this one at a Jefferson County Public Library in Lakewood. Rather than take the computer offline, though, Moonlight Maze investigators decided to keep it running and use it to monitor the intruders. In his book, Rid reports that the FBI obtained a “trap and trace” warrant allowing the task force to monitor the library’s incoming traffic and download log files, giving investigators a better understanding of their cyber nemesis.

John Zacrep, then the library’s IT director, remembers getting a call in 1998 from then-executive director Bill Knot, informing him that the FBI wanted to monitor specific network activity on the library’s servers. “See if you can help them,” Knot told Zacrep.

Robbie Johnson, a computer technician who was working at the library at the time, recalls the day when FBI technicians installed a device called a Thunderbird, about the size of a toolbox, with lots of buttons and flashing lights, right next to the routers in the administrative building’s server room.

“The guys who came in were total computer geeks,” he says with a chuckle. “There may have been a suit with them in the beginning, but the guys I remember were basically dressed informally, so you could tell that they were technicians. They weren’t your typical G-men — G-men don’t do computers. “

But even though the FBI sent fellow computer nerds to do the work, they didn’t tell Zacrep and Johnson much about the investigation.

“I’m a nosy person, and I talked to them, but there were definitely limits to what they could say,” Johnson says. “They were not going to talk about a lot of stuff — that was clear from the onset.”

“The FBI told us that there was criminal activity going on that was passing through our computers, and that someone was trying to hide their identity,” Zacrep recalls.

He and Johnson both say the Thunderbird device recorded only incoming and outgoing network traffic from specific IP addresses associated with the FBI’s investigation.

“That’s all they had to do — they wouldn’t be in the main software of the library system,” explains Zacrep. “So, obviously, there was no patron involvement or fear of patrons being watched.”

Rid, however, says he interviewed sources with both the FBI and the Pentagon who said that investigators could see everything being done on the computer, including the contents of library patrons’ e-mails and searches. “They were very concerned” about the public being surveilled, he says.

Zacrep disputes that library patrons were swept up in the FBI’s investigation: “All I want to say there is: ‘No, that did not happen.’”

But the Thunderbird placed on the Jeffco computer definitely provided the Moonlight Maze task force with a lot of information about the attackers.

All signs pointed to Russia.

Cybersecurity has long been a concern in Colorado because the state contains a number of sensitive targets attractive to hackers, including the U.S. Northern Command/North American Aerospace Defense Command in Colorado Springs, as well as the Air Force Academy, universities with government contracts, like the Colorado School of Mines, and such aerospace-industry heavyweights as Lockheed Martin.

In May 2016, Governor John Hickenlooper signed a bill creating the National Cybersecurity Center in Colorado Springs. Located on the campus of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, the nonprofit is designed to bridge the gap between cybersecurity tactics used by the government and in the private sector.

Hickenlooper says that the center, the first of its kind in the United States, was inspired by an economic-development trip he took in late 2015 to Japan, China, Turkey and Israel.

“We had special phones we’d use while we were in China because the threat of hacks was so intense there,” Hickenlooper recalls. “And in Israel, just because I was interested, we structured almost a full day on cybersecurity.” As part of his tour, the governor spent a few hours at Israel’s National Cyber Center in Tel Aviv.

“What I was really struck by was that almost every single person working in cybersecurity had worked in the military, had taught or done research at a university, and had worked in the private sector in cybersecurity,” Hickenlooper recalls. “So the connection between research, the government and business was intimate. And I came back saying, ‘We don’t have anything like that in the United States.’”

Teaming up with Colorado Springs’s new mayor, former Colorado Attorney General John Suthers, Hickenlooper persuaded the University of Colorado to donate a vacant, 140,000-square-foot building that had previously been a research center for the aerospace company TRW to the cause. Under the direction of CEO Ed Rios, and collaborating with intelligence agencies and such departments as the Department of Homeland Security, the National Cybersecurity Center has developed a “rapid response center” to disseminate information about emerging threats. It also teaches politicians — from county commissioners to city council members — and private businesses how to protect themselves from hacking.

“If you’re a small company — under $100 million — and you get hacked, the FBI just doesn’t have time for you,” Hickenlooper says. “So [the NCC] is the interface between the businesses world, especially smaller businesses, and the federal agencies in which the responsibility for cybersecurity rests.”

Private-sector problems aside, within Colorado’s state government, there are nearly 8.4 million “security events” on any given day, which can range from mistyped passwords to actual attempts by outside intruders to extract sensitive government information, Hickenlooper says.

Among the biggest concerns is maintaining the integrity of Colorado’s elections and voting systems.“If you’re a small company — under $100 million — and you get hacked, the FBI just doesn’t have time for you.”

tweet this

Last month, reports and testimony delivered to the Senate Intelligence Committee confirmed that the voter-registration systems of two states, Illinois and Arizona, were breached in 2016, allowing hackers access to such information as addresses, driver’s license numbers and the last four digits of voters’ Social Security numbers. So far, there is no evidence that actual vote counts were manipulated in any states last November, but the Department of Homeland Security says that voter-registration systems in 21 states were probed or targeted by Russian hackers. (Colorado was not one of them.)

According to Colorado Secretary of State Wayne Williams, Colorado’s voting machines are not connected to the Internet, in order to protect them from hacks. “The voting equipment is kept in a locked room with surveillance and a log of who goes in,” he explains, adding that changing votes would be possible only “if you’re Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol and you have the mask of somebody and you’ve stolen the passwords and you can adjust the seals on the voting machines.”

However, Colorado voter-registration records (a hot-button issue now that Trump’s commission on voter fraud is demanding records from all fifty states) are connected to the Internet, and Williams says the state has implemented cybersecurity measures to protect that database from cyber intruders.

Trevor Timmons, chief information officer at the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office, says that Colorado received two lists of suspicious IP addresses and their patterns of attack from Homeland Security in the lead-up to the 2016 election. The first list arrived last July. And after breaches were discovered of voter-registration databases in Arizona and Illinois, Williams’s office received an additional list of over 700 suspected hacking sources just weeks before election day in November.

“The first thing we did was scan our logs to see if we had traffic coming from those sources,” recalls Timmons, noting that no matches were found.

“Concurrent to that, we blocked access from those specified IP addresses,” he continues. “And once a block is in place, we don’t even allow our computers to communicate with those IPs, so we actually have no way of knowing — without going to Internet service providers — if Russia was trying to attack us after we put those blocks in place because we purposely dropped every electron coming from them.”

In other words, he says, “If someone was trying to rattle the doorknob we wouldn’t even know, because as their hand approached the doorknob, we made the doorknob go away.”

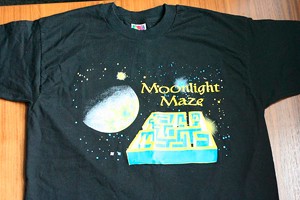

By early 1999, Moonlight Maze investigators were closing in on the culprit, thanks largely to data obtained from sources like the Thunderbird tracking device at the Jeffco library. Certain members of the task force were so obsessed with solving the case that they’d printed T-shirts with a Moonlight Maze logo — a moon illuminating a yellow-and-blue maze — on the front and the words “Byte Back!” on the back.

By now, the team was almost certain the attacks were coming from Russia. They even noticed that the hackers were active on December 25, 1998, but dormant on January 7 and 8, 1999: Orthodox Christmas in Russia.

On February 25, 1999, investigators felt confident enough to inform the House and Senate Intelligence committees that the cyber campaign was being carried out by the Russians. The committees were shocked by the report, and one member of the House comittee, congressman Curt Weldon from Pennsylvania, went public with some of the revelations.

On March 4, 1999, ABC News broke a story about Moonlight Maze and Russian hacking of government and military targets in the United States. But according to an FBI memo obtained by Rid, “In spite of the ABC story…the intrusions continued.”

Soon, however, the FBI got a major break: A Russian-language news website published a defamatory article about the daughter of then-Russian president Boris Yeltsin. Infuriated, Yeltsin set his Ministry of the Interior (MVD) in pursuit of the publisher for libel, and the MVD discovered that the website was hosted not in Russia, but in California.

When Russian police asked the FBI for information related to the website host, the feds saw an opportunity for an information exchange. The FBI produced the logs that the Russians wanted and then requested information related to five cyber intrusions, without revealing the extent of the Moonlight Maze investigation. The FBI also obtained a verbal commitment of cooperation from a member of Russia’s MVD, Vitaliy Degtyarev, who agreed to host a delegation of U.S. investigators in Moscow."We’ve gotten thumbs up from people — especially from people in government agencies — that were involved in the original investigation."

tweet this

On April 3, according to Rid’s book, seven members of the Moonlight Maze task force, including two female FBI agents, arrived in Moscow. That first night, they were hosted at a dinner by Degtyarev and another general with the MVD. “So, what brings you to Moscow?” Degtyarev asked.

The dinner got out of hand after the Russians kept producing bottles of vodka, first toasting to America, then Russia, and then, as Rid writes, “later in the evening, to women.”

One unnamed source told Rid that a Russian general, shitfaced on vodka, began hugging the two female FBI agents. He then stuck his tongue into one of the woman’s ears.

“She was dumbfounded,” Rid says in his book. “The agent rushed to the ladies’ room with her FBI colleague. ‘He stuck his tongue into my ear,’ she said, enraged. ‘Did he stick his tongue into your ear as well?’ ‘No,’ the other agent responded, incredulous. The two women considered their options. They quickly agreed that they did not want to cause an international diplomatic incident. ‘Just wipe it out,’ the FBI agent told her colleague.”

Thomas Rid, David Hedges, Daniel Moore and Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade (from left) in London.

Kaspersky Lab

But the sleuthing at Cityline appeared to have touched a nerve, because rather than take the American agents to other ISPs they wanted to visit, their Russian handlers spent the remainder of the trip hosting them on unwanted sightseeing tours.

But even that development was revealing. An internal report, written after the Moscow trip, notes that the task force suspected some miscommunication between different branches of the Russian government. Investigators surmised that the Moonlight Maze cyber campaign was probably high up and secret enough in the Kremlin that the MVD did not know about it, and so the MVD probably thought the FBI agents were looking into a criminal case rather than investigating state-on-state cyberwarfare. That would explain why, after the Americans visited Cityline and showed their hand, they were sidelined for the remainder of their Moscow trip.

Soon after that excursion, the FBI ended its involvement with the case, and the Moonlight Maze task force was disbanded. All investigations shifted to the Pentagon, signaling that the U.S. government had officially concluded that the attacks were not private criminal acts, but diplomatic in nature and extending to the highest reaches of the Russian government.

The attacks didn’t stop, of course. Russian hacking became more and more sophisticated, even using satellite uplinks to further obfuscate the origins of the intrusions. To the Pentagon, it was clear that the United States was engaged in a permanent cyberwar, a digital arms race that continues to this day.

In fact, a final layer of intrigue was added to the Moonlight Maze chronicle as recently as this April, when Rid and digital forensics experts with the cyber-security company Kaspersky Lab released a report linking the ’90s attacks to a legendary but shadowy hacking group known as Turla, which is still active.

The breakthrough came when Rid and members of the Kaspersky Lab team, including senior security researcher Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade, discovered an old computer used by the Moonlight Maze attackers that was still in working condition.

Like the Jeffco computer, this machine, named HRTest, was used as a proxy by the Russians through which to route attacks; it, too, was in an unassuming location: a nonprofit organization in Wimbledon, England. As with the Jeffco computer, investigators had learned about the machine in 1998 and, rather than shut it down, had installed tracing software to record and monitor all of the hackers’ activities.

Thanks to a redaction error in one of the documents Rid had received from the FBI, he was able to locate the computer’s administrator in England, a man named David Hedges.

When Rid reached Hedges by phone in early 2016, Hedges said, “I hear you’re looking for HRTest.” He then kicked a machine under his desk, and reported, with a laugh, “Well, it’s sitting right here, and it’s still working.”

“That was entirely miraculous. I mean, it was such a moon shot to discover the thing,” says Guerrero-Saade. “We were hoping that maybe we’d find some logs or something along those lines. We never thought that we’d run into an actual [working computer] and have all these samples still on it.”

Guerrero-Saade says he’d already had a suspicion that the hacking group Turla, which is Russian-speaking and “extremely innovative,” given its use of satellite uplinks and infected USB drives to go after off-line military and diplomatic targets, was somehow involved with Moonlight Maze.

Now it appeared that his suspicion was correct. Comparing more recent Turla attacks with files on the HRTest computer from the Moonlight Maze days, Guerrero-Saade and his team found a commonality in a source code called LOKI2, used to exploit Unix- and Linux-based software and operating systems.

“What LOKI2 does is tunnel information from one computer to another, going through pipes or protocols that normally don’t carry that type of information,” Guerrero-Saade explains. “They basically figured out that they could use the sewers or the ventilation ducts to get in and move information around and stay undetected.”

The LOKI2 code base was developed as far back as 1996 — the same time that Moonlight Maze got under way — and Guerrero-Saade says the discovery strongly suggests that Turla was involved even back then, which could make it the oldest hacking group in the world.

The report’s findings have gotten significant attention in the cyber-forensics community. “Without naming anybody, I’ll say that we’ve gotten thumbs up from people — especially from people in government agencies — that were involved in the original investigation,” Guerrero-Saade says. “It’s a good indication that we’re on the right track. Because this is a story that’s not complete yet.”

Yet even if Turla was definitely involved, does that tie the Russian government itself to the Colorado School of Mines attack? There’s some indication that Turla is associated with the Kremlin (the group only seems to go after diplomatic and military targets), but Guerrero-Saade says he’d need irrefutable hard evidence to say the Moonlight Maze incidents were ordered by the Russian government. And so he hopes to find another “moon shot” like the HRTest computer to show what the group was up to between 2000 and 2004, when the trail goes cold.

“We’re holding out hope that we’ll get that next piece,” he says.

Rid’s investigation has convinced him that Moonlight Maze marked a major turning point in geopolitics

The attacks are more than just a historical footnote, he says, because “the future began with Moonlight Maze. Espionage now looks more like Moonlight Maze than anything that we saw during the Cold War. It really was the beginning of the new era, and it’s never really stopped.”

Since the release of his book, Rid has been investigating Russian intelligence operations around the 2016 election. In June of last year, he was one of the first experts to publicly call out Russia as being behind cyberattacks disrupting the Clinton campaign. And on March 30, he was invited to testify before the Senate Select Intelligence Committee at its first open hearing on Russian interference, an appearance he calls “one of the craziest events of my entire career in terms of its visibility.”

In front of the committee, Rid discussed Moonlight Maze and its direct relevance to Russian cyber operations that aimed to undermine the 2016 election. “In the past twenty years, aggressive Russian digital espionage campaigns became the norm,” he told the senators. “The first major state-on-state campaign was called Moonlight Maze, and it started in 1996.”

Rid isn’t surprised by the revelations about the Russians that have continued to spill out since he testified several months ago. “The only thing that’s surprising is — if you study Cold War history and how Russian intelligence operated back then — that it took them so long to combine hacking and leaking, because they’ve done both for a very long time, but hadn’t combined the two until 2015 and 2016.”

And if Rid’s documents are accurate, the campaign stretches back to a lowly computer at the Colorado School of Mines in 1996.

But for David Larue, the retired Mines IT administrator, the notion that the baby_doe computer was hacked by the Russians in the opening salvo of the first state-on-state cyberwar remains little more than an abstract curiosity, and one on which he’s not entirely sold.

“I’m still a little skeptical myself,” he says today. “But I will admit it’s a real possibility.”