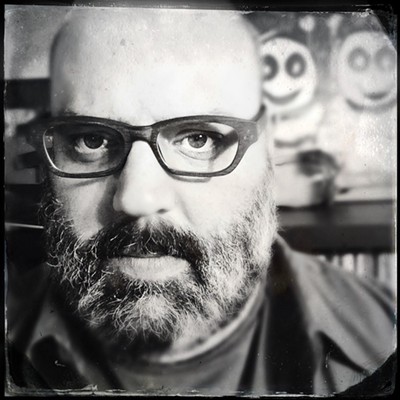

DJ Rick Crandall started at KEZW-AM 1430 in 1991 with the sole purpose of babysitting the station for three months while its owners were considering selling it. Although the station has changed hands a few times since then, Crandall ended up being there for thirty years — until now. Current owner Entercom Communications, which bought KEZW in 2002, just shifted formats from classic music to the sports-betting station 1430 AM/The Bet, and Crandall is out.

He signed off one last time on Monday, January 25, before the station changed formats. He says KEZW was one of the last of its kind — the adult-standards format — in a major market.

Crandall was 34 when he started the gig. On his first day on the job, a listener called to gripe about how he had misattributed one of the songs: “That was Tommy Dorsey, not Glenn Miller, you idiot. You're not going to last very long.”

That listener was wrong. For the next three decades at the station, Crandall, who went on to become KEZW’s program manager and Breakfast Club host, not only spun music of the big-band era, but also played songs from the ’40s through the ’70s, including classics from Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra.

“It was a radio station that every program-director book will tell you shouldn't exist,” Crandall says. “It just doesn't fit any kind of reasonable pattern to how this works, but it worked in Denver, and it was partly my relationship with the audience that kept it going, and then the work we were doing in the community.”

Part of that community included World War II veterans. During his first year at the station, Crandall, who honed his radio chops in the Air Force, when he was stationed in Guam in 1976, was asked if he wanted to interview World War II vets on the fiftieth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I was still trying to figure out my connection, being 34 years old at the time, trying to connect with 70- and 75-year-olds,” Crandall says. “I had seven Pearl Harbor survivors who ended up showing up that morning. We were cramped in the smallest studio in the building, and I held up a microphone as they each told their stories. It was an hour I let them talk. It was the most powerful hour I had ever experienced in media to that point, because as they were telling their stories, I could see in their eyes that they were actually reliving it.”

In 2000, Crandall went on to do a broadcast from the Normandy American Cemetery, which is on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach in France; he spoke from the USS Missouri for the sixtieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor the following year. During the visit to Normandy, he was struck by how many Coloradans had given their lives and service and had been killed in military action. He started to do more research, and was given a list of 5,200 Coloradans who had been killed in war since the state was admitted to the Union in 1876.

Crandall set out to build a memorial for those Colorado veterans, and finally finished the Colorado Freedom Memorial in 2013 after putting twelve years of work into the paneled glass structure in Aurora, where he grew up. It lists 6,218 Coloradans killed in action; he and his team keep discovering new names as they do more research.

“It goes to show what's possible when you and your audience are aligned and working toward a common goal," he says. "The listeners of the radio station are incredibly supportive, and donated most of the money we needed to build the memorial."

While other stations around the country were playing similar kinds of music over the past few decades, Crandall says they weren’t doing the community outreach that he and other staffers at KEZW did with local veterans.

“It took a lot of effort and a lot of energy,” Crandall says of the station’s work with the community. “There were young kids that I cross paths with who were just beginning their careers in radio, who, like the old guy down in the corner studio, were willing to help me with what it was I was trying to do.”

While listeners tuned in for big bands and crooners, Crandall also became their news source, particularly for a generation that still wanted to get information through the radio. He’d relay current events, talk about the weather, and mention concerts they might want to attend.

Listeners also got to know about Crandall himself. “They knew my wife and my children,” he says. “They knew everything about me. Nothing was really hidden from them, and it got to the point where I think they believed that I was part of their family. And that's what needed to happen for this to succeed.”

Some listeners got to know him personally on some of the cruises around the world that he hosted over the past twenty years. “It was like I didn't have a vacation for 21 years unless forty people were walking around behind me or in front of me,” he says. “But I was seeing the world with listeners, and at the same time building a bond that was pretty incredible and making lifelong friends.”

Crandall says he’s heard from some listeners who tell him their parents played Crandall’s radio shows while making breakfast for them and getting them ready for school. Those same children, who grew up on his show, are now adults and say, "Now I've got a kid, and I'm feeding them breakfast and listening to you.”

“It was just the coolest thing to know that many generations have grown up enjoying it,” Crandall says. “Not many radio stations can say that, honestly.”

Crandall, who went to high school in the ’70s and listened to rock acts like Chicago and the Doobie Brothers, found it funny that he spent thirty years playing big-band music.

“Somehow this made sense to me,” he says. “It could be because if you love music, genres start to blend. If you're just passionate about good music — and there were enough people in this town that were passionate about good music — you thought KEZW was just cool enough to be cool.”

During his time at KEZW, Crandall learned about music of the big-band era and became a big fan of Miller. He also got to work with Alan Cass, who curated the Glenn Miller Archives at the University of Colorado Boulder before passing away in 2018.

Crandall's love for the era runs so deep that he’s considering writing a book about big bands and the venues that hosted them in Denver in the ’30s and ’40s, including the Trocadero Ballroom, which was part of the original Elitch Gardens in northwest Denver, and some of the many joints on Broadway.

“I said all along that when this ended, it would probably be a good run in radio and it'd be time to do something else,” Crandall says. “We'll see if that’s true. There's still some work to do out at the Colorado Freedom Memorial. We want to build a visitor center out there.”

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]