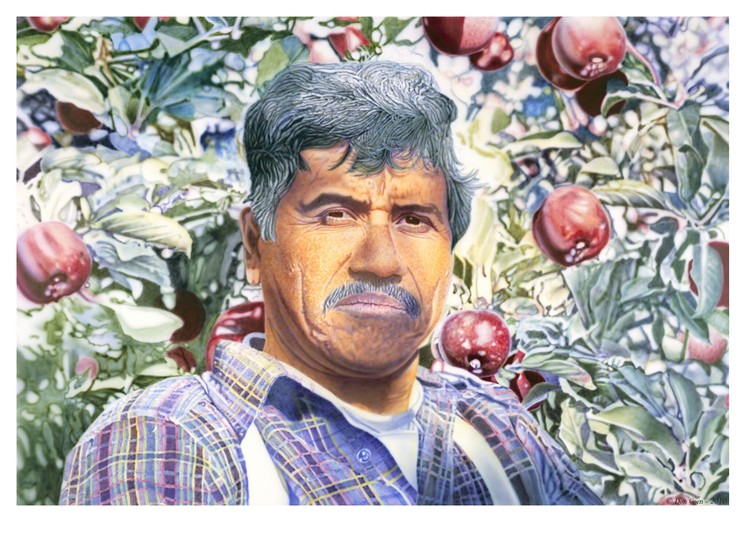

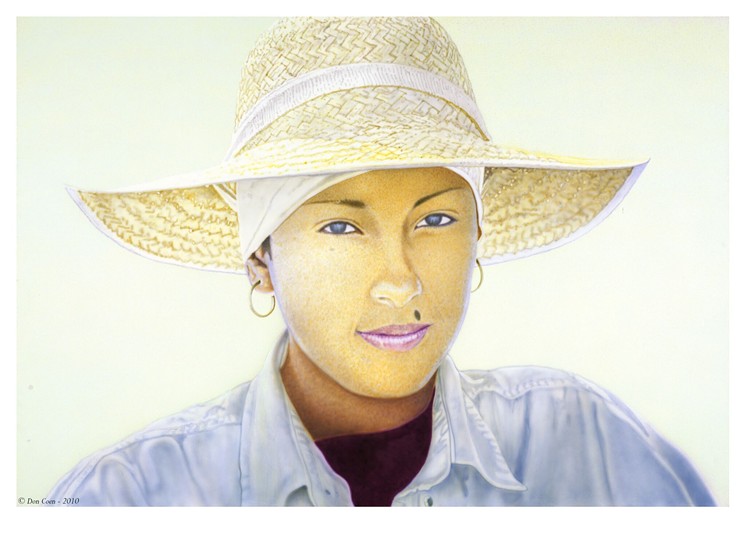

Painter Don Coen spent roughly twenty years working on a series of fifteen paintings of migrant workers, on display at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center through May 14. The artist, who entered his career as a non-objective painter, shifted toward depicting landscapes and, ultimately, portraits based on photographs. While some describe his paintings as photo-realism, Coen prefers that viewers see them as cinematic. Rich with drama and character, the series on display at CSFAC aims to bring viewers up close to the migrant farm workers whose labor keeps the United States fed.

Westword caught up with Coen to talk about the paintings.

Westword: Tell me about the show in Colorado Springs.

Don Coen: Well, there are fifteen paintings. They're seven-by-ten feet, except there are two of them that are seven-foot square. They're airbrushed acrylic, sixty layers of paint. Now, I say sixty layers of paint, but there are some areas where there is no paint. I don't use black or white paint, and so my paintings are very transparent. But I slowly build up layer over layer over layer, and I gesso the canvas seven times so I have a beautiful, white surface. So where I want a real light color or just a surface left white, it's just the white of the canvas that you see.

Many years ago, I used to do a lot of water, and I think that's why I paint transparent the way I do. But I also love to use pencil as a texture in my paintings, and so I have carried that over and used that in these paintings.

For many years, I painted non-objective. Some of my images were triggered by 2001: A Space Odyssey. I spent all those years painting non-objective, where you only deal with color, shape, texture, form, pattern, and you don't have an image, and so I learned to think about painting that way. There is absolutely no way that I would ever be able to do paintings that are "realistic" if I hadn't spent all those years painting non-objective, because I learned just to look at the image and be able to interpret the image from that.

When I first switched from non-objective to realism and did the Lamar, Colorado, series, one of the first paintings that I did was this painting of a cow drinking out of a water tank. I remember thinking as I was getting ready to start that painting: "My God. Water doesn't look like this. I can't paint water that way." We all have a vision in our mind of what we think something looks like, and then I said to myself, "Well, I'm just going to paint it like it looks here, and then maybe when I get back, it will look like water." And sure enough, it did. It was extremely helpful that I spent all those years painting non-objective.

Often for artists, the trajectory goes in the opposite direction, from realism toward abstraction. At least, that's the traditional narrative. I'm curious what your thought process is shifting from abstraction toward representation?

I started doing art when I was a real small kid. By the time I was ten years old, I literally had stacks of drawings, and I drew realistic until I went away to the University of Denver to get my first degree. At that time, everybody was painting non-objective. In fact, if you didn't paint non-objective, they cut your arms off. Well, I didn't want them to cut my arms off. But what I discovered, of course, was that I loved painting non-objective, because there was a certain freedom to it, there was a certain way of painting that was very freeing. It freed your mind and your thought patterns, and I loved it. Then, after that, I painted non-objective.

I grew up in Lamar on a farm. After I got out of college, I'd go down there a lot, and I found I was becoming more and more affected by the landscape of Lamar. So, gradually my paintings went from what I call non-objective to interpretive landscape, and I painted that way for quite a while. Then, one day, I had a friend who said, "Hey have you seen this new movie called 2001: A Space Odyssey." I said, "No." He said, "Oh, you've got to go see it." Well, I went to see Space Odyssey, and it never occurred to me for a second what was going to happen. I went in and saw that movie, and I came out, and I never painted the same again. I went home, and I thought, "Oh, my God, these paintings that I've been doing, they don't make sense to me anymore." And so I did my first "space painting."

The paintings from the space era were actually paintings about Lamar. But if you've ever been on the plains around Lamar, there is this incredible feeling of space that you have when you're out on the prairies. So a lot of the experiences I had as a kid growing up were carried over into those paintings. And I painted that way for probably twelve years.

And then, ironically, I was down in Lamar with my friend, Larry, and we were goose hunting up at Neenoshe Reservoir. There was this incredible sky that was so beautiful that neither one of us could even speak. And then finally Larry turned to me, and he said, "Hey Don, you love this area down here so much, you should paint this area." I decided to make a statement about contemporary rural America and what I thought contemporary rural America was really like, as opposed to people that paint the little broken-down barns with the owl peeking out of the window. So I did 4,000 slides of Lamar, and I started the Lamar series, and I ended up doing fifteen paintings, just like the migrant series, and I spent three years doing that series of paintings, and they opened at the museum in Colorado Springs. Mid-America Art Alliance came, and they saw them, and they said, "Nobody's painting rural America like you are," and they said, "Can we tour this show?" and I said, "Sure." So they toured it for three or four years through museums through the West.

After Lamar, then [I started painting] rural America. One day in the early ’90s, I was up at Greeley and I was photographing these cows, and I turned around, and I saw these migrants sitting on these sacks of onions, and I saw the way the light was shining through their bandannas. I thought, "God, that's a beautiful image." So I walked over and I said, "Hey, would you guys mind if I took your picture?" They said, "No, go ahead." I took a bunch of pictures of them, and I started back to Boulder.

I thought to myself, wow, I grew up around migrants, but I've never really seen them until today. I thought, You know, nobody has ever painted the migrants. I've seen photographs, but nobody has ever made a major statement about migrants. So I thought, well, maybe I should be the one to do it, because growing up around them and growing up on the farm where I worked every bit as hard as the migrants did, I have just incredible appreciation for what they do and the hard work that they do.

I thought, I'm going to give these people a face. So I committed to doing this long project. I spent nine years going across the United States photographing and documenting migrants. Then I started this series. I had a couple of other shows during that time, but I spent almost nine years doing the fifteen paintings you can see now in Colorado Springs.

Wow.

[Laughs.] It's a lot of time.

For fifteen paintings, it is. That's amazing. It's amazing to have such devotion to fifteen paintings and to the subjects you're painting.

I'm so emotionally involved in this series. I really love these paintings, because it really speaks to what these people do. [When people walk into that museum], I think they're going to come out of that show with a completely different thought: Wow, this is something else.

In fact, when Lewis Sharp, who was at the Denver Art Museum, first came up — and he spent two or three hours looking at [the paintings], at one point he turned around and grabbed me by the shoulder. He said, "Oh, my God, Don. Do you have any idea what you've done? You've taken these people that nobody knows, that nobody has ever even thought about, and you've captured their souls." So, anyway...

The migrants you painted are from all over the country, correct?

The last one that I did, it's the guy with the yellow background, that was in Immokalee, Florida. They were from California. There were several from Colorado. They were up in Oregon, up in Washington, Florida, different states. I'd just go and take tons of shots, never knowing which one I was going to select to do until I got home and started going through the images and looking at them.

What do you hope audiences experience with these paintings?

I hope, if nothing else, this gives people a real appreciation for what the migrants do. I think they do an incredible thing for our country.

Don Coen: The Migrant Paintings is on display through May 21 at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 30 West Dale Street, Colorado Springs. For more information, call 719-634-5581.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]