Mensa is from Chicago and first caught tastemakers' ears circa 2009 as part of Kids These Days, a rap-infused rock band. The combo broke up in 2013 before making a national splash, and in short order, Mensa went solo and signed to Roc Nation, Jay-Z's entertainment-biz juggernaut. Since then, his growing reputation has caused him to cross paths with, among others, Kanye West; the uproar after Mensa was removed from The Life of Pablo track "Wolves" led ’Ye to "fix" it by reinstating his contribution.

The Autobiography, released this summer in the wake of an excellent EP called There's Alot Going On, includes cameos from an impressive roster of big names, including Pharrell Williams, Pusha T, Ty Dolla $ign, Chief Keef, The-Dream and, believe it or not, Weezer. Still, there's not the slightest doubt whose story is being told over the course of fifteen cuts that explore joy, heartbreak and everything in between.

In the following Q&A, Mensa touches on gun violence in Chicago and beyond, a tale of near-electrocution at the Lollapalooza festival, his decision to reveal suicidal feelings with which he's grappled in the past, the way Jay-Z helped him to find The Autobiography's most effective form, and the startling yet inspirational way he put himself in the mind of a man who killed his best friend.

Our conversation took place last night, November 2, after Mensa had spent the better part of an hour being fingerprinted and vetted for entry into Canada, where his tour with Jay-Z heads later this month. His frustration over the process gets the discussion off to a running start.

Vic Mensa: I had the FBI and all types of extreme measures.

Westword: That's a sign of the times, isn't it?

It is. The world, man. People don't know how to deal with what's going on these days, and how could they? It's been predicted, but people were upset when Malcolm X said that the West's chickens would come home to roost. I have the most sympathy for anyone lost in all this senseless violence. But this is a product of Western civilization just destroying and cannibalizing the rest of the world. And itself, you know? Our gun laws are a fucking mess, so that people can make money. What can we do except search every shoe and every wallet? It's a shame, but it's real.

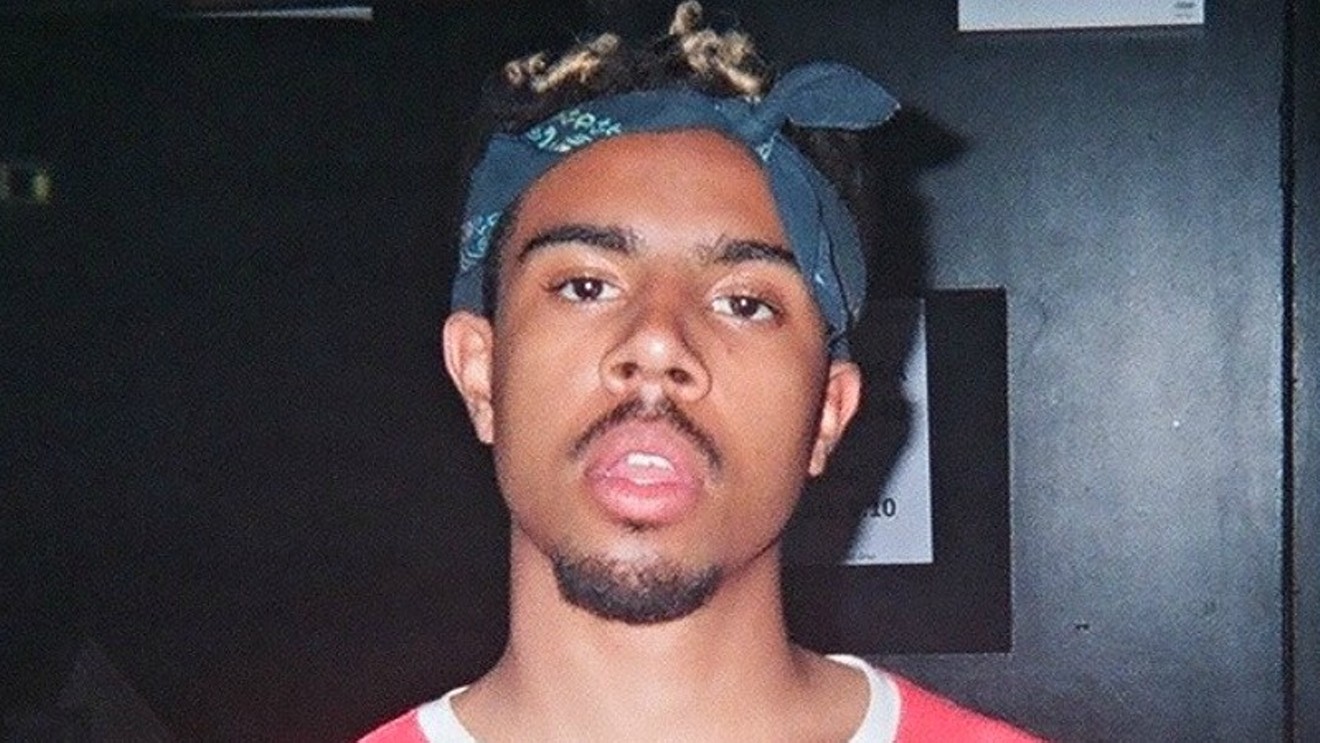

Vic Mensa in the video for "There's Alot Going On."

I feel that the present and the future really depend on us bringing the truth to light. And people are important to me — because I'm one of them. [He laughs.] You know what I mean? We have this separation mentality — this separateness that defines and dictates our society. It's every man for himself and every dollar to be had. And dignity is sold to the highest bidder.

We're forgetting that we're part of this global community. It's really a community at the end of the day, and when we all start running out of water and clean air to breathe, we're going to realize that we're in this shit together.

I already realize we're in this shit together, because I've got people back home dying of gun violence. I've got people back home spending twenty years in prison from gun violence. I've got other friends of mine jumping from Percocets and Xans, and now they're shooting up heroin. I'm just seeing how fucking in-this-shit-together we really are. And I'll be damned if I have a platform and a voice that can at least shed light on the reality of these situations and not use it. Then I would feel like I'm part of the problem, and I want to be part of the solution.

Speaking of the problems, a lot of people, when confronted with these kinds of issues, tend to either bury their head in the sand or create enemies out of anyone who's different from them. Why do you think so many of us react that way? Is it easier to demonize others or run away from a problem instead of facing it?

Human beings desire comfort and familiarity. When we're in such a time as now, when chaos and imbalance is the norm, then taking that step to change things — that's stepping into uncharted territory. We in Chicago, we don't know a time when violence was not the law of the land. They would have you think that this ultra-violence we're experiencing today is a new phenomenon, but the only new phenomenon is Twitter. It was this bloody in the ’90s, and I was born in the ’90s.

A lot of people, they just throw their hands up and go, "This is what it is." And if you're in the streets, you act accordingly to try to live. If you're not in the streets, you get out. And if you're outside of Chicago, you just point and say, "Well, look at Chicago. Look at how fucked up that is. Seems like there's nothing we can do about it." Because peace is such a foreign idea.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn't strive for it, as difficult as it might seem. I know I don't enjoy paranoia. I don't enjoy living my life in fear. I want to change that. I want to change that for myself. I want to change that for my children when they're born. I want to change that for my little homies growing up. I want to change that for my friends' kids. We can't run away from this shit. We were handed all these problems.

Vic Mensa as seen in the video for "Rollin' Like a Stoner."

I was pretty head-over-heels for a Spanish foreign exchange student who was staying with this friend of mine. I took her on a tour of my neighborhood — Hyde Park, on the South Side — and I was bringing her back to reunite with her host. And I sent her into Lollapalooza, because she had tickets and I didn't. So I thought I would just sneak in, but it turned out to be very difficult. I tried to climb off of a thirty-foot bridge — tried to climb down a metal gridiron structure and got zapped.

I fell on the tracks, and I was in the hospital for some time. And when I got out, I flew out to New York for my first-ever record meeting. I got an offer to record for $3,500. [He laughs.] That was a pretty defining moment in my life — something that really made me feel I had a purpose. I think everybody has a purpose, but maybe it was a moment that put things into perspective for me. I've rarely felt so happy to be alive and be present as I did on that first day out of the hospital.

After that, my dad took me to Africa. I'm Ghanaian, and we did some voodoo praying to the ancestors; some of his family practice voodoo. So we did some praying to the ancestors — just thanking them for watching over me in that moment.

There are so many different emotions on the album, and on the song "Rage," you talk about the other side of things: suicidal feelings. Was it empowering for you to be able to speak about that subject, even though it's so personal?

I think it was empowering. If you can't name the affliction, then I don't think you can heal it. That was what a lot of this album was about for me — really diving deep and soul-searching in a way that helped me identify defining moments in my life and things that influenced my thought processes and my actions of today in order to ultimately try to be free. That's why the last song on the album is "We Could Be Free." I'm going through all of these experiences and remembering things I haven't thought about and analyzing them and drawing these parallels and these connections in order to try to be free of pain, of the past, of doubt, of stereotypes, of limitations, and of anything else that would impede my ability to really be present and to be unchained.

You've talked about conversations with Jay-Z regarding the arc of your album, and it made me think of a screenplay or a novel — that it needed to have a beginning, middle and end, and dramatic tension. Is that the way you looked at it? Did you want it to be a complete story that took the listener on a journey?

Yes, definitely. And that was something Jay-Z was really instrumental in helping me to shape. Because clearly, he's done it once or twice, you know. [He laughs.] I had a lot of other songs and small bits and pieces that didn't end up on the album. He was helping me step outside of my attachment to these things. Everything was a true story, so I felt attached to everything. So it was about not belaboring one specific point so I could keep your ear as a listener and give you a well-rounded, full picture.

The things I have to say on and off the record are important, and I say them because I want to be heard. He was helping me make sure I was heard.

We seem to be in a musical period when fewer artists are putting together album-length projects that hold together as a unit. We're seeing more singles, or collections of singles, supposedly because listeners have such short attention spans. Do you think we're selling them short? Do you feel that if you give them something meaty and significant like The Autobiography, they're capable of spending the time needed to get everything out of it they can?

I think when your intent and your energy is authentic and it's real and it's of the moment and it's necessary, it will reach the people it needs to reach. It's a time in the world, in society as a whole, where we're trying to figure out how to deal with the tools at our fingertips and things that can sometimes obscure more important messages. Think about your phone. You can get a text from your mom saying, "The house is on fire. Please help." But if you're getting five Twitter mentions at the same time, you might miss what's really important, because there's all this sensory overload.

I've been impacted by albums in a real way. Somebody like Common, who had these vast, important albums that took you so many different places. Or Kanye or Radiohead. A group like Radiohead stayed away from fucking singles after doing it one time. And you know what? They've gone down as being so much more important than some of their contemporaries who played that game.

"Heaven on Earth" is one of the most artistically and thematically challenging songs on the album — particularly the third verse, where you get into the mind of a person who killed your friend and are able to portray him as feeling a sense of remorse. Is it an easy trap to assume that certain people are either all good or all bad, because we're all more complex than that?

One of my main goals in writing this album was to paint a comprehensive, multi-faceted portrait of my experience — the experience of a young black man that is hopeful and woke, but that also shows how he can be trapped by drug use and hyper-masculinity and violence. How he can be all these different things at once. Be a lover and be a fighter. All these things.

I wanted a listener to come away forced to feel empathy. That's what the world is missing: empathy. So when I was writing "Heaven on Earth," I had to take an empathetic perspective, because I've lost friends to violence from both angles. I have people close to me who have killed. I have people close to me who have been killed. And they're really all victims.

That's not a goal. I'm not trying to victimize my people and shit. I'm just trying to show that nobody wins in that situation. When you look at an epidemic like the violence in Chicago and, on a larger scale, in the inner-city black communities of America, there are no good guys and bad guys. There is no good; there is no bad. There are just human beings. A small twist of fate can either turn you into a killer or into a dead man, and in a lot of situations, it can happen to anybody.

For you to find hope in that darkness was really moving to me as a listener. Is that something you aspire to? Do you want to show people that even in the darkest times, there can be light?

One hundred percent. I think it's awesome that you could resonate with that in that way, because that's what I want with music. I don't want only young black people that listen to my music be able to appreciate it. I just want people to be able to appreciate it. I want to make music that can make a person from fucking rural Pennsylvania who doesn't even really like black people appreciate it, if they come into it with an open mind and an open heart.

Just bring people together. That's all. I want to make music that can unite people as opposed to exacerbating our differences and our separations. Like I said earlier, I feel like we're plagued by that separateness. At its essence, we're all coming out of a woman and going into the dirt. There's a lot more power to be found in togetherness than there is in opposition.

Vic Mensa, 8 p.m. Sunday, November 5, Pepsi Center, 1000 Chopper Circle, $29.50 to $175.50.