Christina Hoff, another refugee who’d landed at South a few years earlier, helped out as an informal interpreter with new arrivals from Burma, and also helped Thorpe understand what refugees from that country had experienced. Thorpe shares Christina’s story in “Silly One,” a chapter from The Newcomers excerpted here:

Christina gave me a brief outline of her past on the very first day we met. She was twenty-one years old. Her first language was Karen; she also knew Burmese and Thai. Burma was much in the news, and the stories coming out of that country resembled the story that Christina told: She had fled from her home village inside of Burma at the age of three, and then she had spent almost a decade in a refugee camp in Thailand. She had entered the United States as a refugee at twelve, and shortly after resettling in the United States, her grandmother had tried unsuccessfully to marry her off to a much older man.

That had been during her eighth-grade school year, her first year in the United States, back while she was still getting used to everything. One day that year, she had worn flip-flops to school during a snowstorm, because she had never worn regular shoes before. Christina’s grandmother wanted to give her away to a man who was more than ten years older than she. Christina described one encounter with her supposed “fiancé.” He had shown up at the door of her apartment and demanded that Christina perform sex acts; she had refused and threatened to call the police. I told Christina that I thought she was incredibly strong to have known at the age of thirteen that she did not have to “marry” the man to whom her grandmother had given her.

“I was thirteen!” protested Christina. “You don’t even know what love is at that age! I’m twenty-one now, and I still don’t know what love is. Jesus Christ!”

Subsequently, she and her two siblings had been adopted by an American family. “I love my family!” Christina gushed when speaking of her adoptive parents. “I have the best parents in the whole world.”"When I heard that I would come to Colorado I was scared and nervous."

tweet this

After we knew each other better, Christina introduced me to her adoptive parents. They lived in a comfortable two-story house in the southern part of Denver. Martha, her adoptive mother—a woman with cropped iron-gray hair, a hefty bosom, and a world-wise manner—happened to be wearing a magenta T-shirt, black shorts, and a clunky leg brace.

“You hurt your leg,” I said to Martha.

“Well, I have MS,” she replied, in the tone of voice someone else might use to say, Oh, I have a little cold.

Christina’s adoptive father, Steve, was a slim, bespectacled, kind-faced man in worn-looking jeans who was transplanting things out in the garden. I followed Christina to the kitchen, where she was cooking. It had become a form of self-expression to prepare recipes she remembered from Burma and Thailand. She had gotten to the point where she was creating her own concoctions, such as the one she was busy making, a mustard-colored curry into which she was placing hard-boiled eggs. The kitchen smelled of turmeric, garlic, ginger, and lime leaves.

“What do you call that?” I asked Christina, expecting to hear an exotic name in Karen or Thai.

“Egg curry!” she said.

In her “Autobiography,” as she had titled a paper that she wrote in high school, Christina had written about the family members who had taught her how to cook:

When I learned how to cook, my mom was the first one who taught me, but she wasn’t a nice teacher. She always taught with anger and she always got mad at me without a reason….

My uncle Sha Moe Ko was the one who later taught me how to cook and he was really nice to me. He was always patient with me when I learned how to cook. He taught me his favorite recipes and I really like his recipe for Kaw Now. Sometimes I cook his favorite recipe to remember him as my uncle. And I remember the day I lost him because of a landmine that blew up in front of my face; it was really a surprise. I myself cannot believe why it didn’t happen to me in place of my uncle. Many people were surprised that happened to him, not me, because I walked along that road every day. He was my favorite uncle and a kind uncle. I am glad he taught me how to cook before he died. I will always miss him. To remember him I cook his favorite food that he taught me.

Her uncle’s favorite meal was chicken curry. The egg curry we were going to have for lunch today was a variation on that theme. Christina had also prepared white rice and green beans. When the meal was ready, eight of us sat down at a long wooden table, with sun streaming in the windows. At the table were Martha, Steve, five of their seven children, and me. The couple had three biological children, a daughter they had adopted from China, and the three girls from Burma. Steve warned me about the chili paste that one of Christina’s sisters put on the table, advising that I use a minute amount. Martha added, “Two or three molecules and you’re set.” I put a tiny dab on my plate; Christina stirred three or four spoonfuls into her food.

The three Karen girls took turns getting up from the table and draping themselves over Martha, half lying along her shoulders, or went down to the other end of the table and huddled against Steve. Martha explained that she had used physical affection as a tool to reassure the girls during the difficult transition from the kind of home they had once lived in to this place.

After lunch, Steve wandered back outside to work in the garden, the other kids disappeared upstairs, and Christina, Martha, and I stayed at the table. Martha listed the various traumas that she had gradually discovered, over many years of parenting. “You know, they’re going to school and they don’t know the language and there are all these cultural issues, but then underneath there’s also trauma at the same time, and nobody at the school knows about it, and they’re navigating all of that,” Martha said. “It’s so hard to tease that out from just ‘doesn’t speak the language,’ which is also true, of course.”

Martha went upstairs to gather some books she thought I needed to read to understand what was happening inside Burma. One of the books she recommended was For Us Surrender Is Out of the Question, by Mac McClelland. The book includes a hilarious scene in which McClelland temporarily moves in with some Karen activists who are living on the border of Burma, just inside Thailand. Upon her arrival, McClelland is shown around the house, where she sees a concrete trough filled with cold water. A Karen man pantomimes pouring cold water over himself, using a small bucket. McClelland engages her housemates in a prolonged conversation about showering, in which she eventually realizes that nobody else in the house, at any point in their lives, has ever taken a hot shower. They are skeptical. Even when she attempts to convince them that bathing with hot water is pleasurable, the Karen activists are dubious. One of them insists stubbornly that cold water is better. McClelland uses the story to illustrate the naivete of Americans; we just take our hot showers for granted.

Christina’s favorite book was Undaunted, a memoir by Zoya Phan, a Karen-speaking young woman whose father was a leader in the resistance movement. From the material Martha shared, I learned that the military regime in Burma had created more child soldiers than any other country in the world. The Burmese military also encouraged its soldiers to employ rape as a tool of war, and had used land mines so rampantly across its own territory to suppress various ethnic groups that Burma was the most heavily mined country in the world. The Burmese military was also accused of beheadings, the butchering of infants, deliberate starvation of entire villages, and additional atrocities. Of all the countries in the world, Burma had sent the largest numbers of refugees to the United States during fiscal year 2015. It sent the second largest number after the Democratic Republic of Congo during fiscal year 2016. Politicians were debating the refugee crisis as if it was something taking place in the Middle East, but their understanding of the matter appeared deeply flawed.

At lunch, Martha explained Steve had met Christina first. Steve belonged to the First Universalist Church of Denver, and he had volunteered to mentor a newly arrived refugee family—Christina, her two siblings, and their grandmother. When he had come home bearing a photograph of the three Karen-speaking girls, Martha had taken one look at the faces of the girls she had yet to meet, and asked, “Where are the parents?”

Christina was born in a small village in Kaw Thoo Lei state, which literally means “a land without evil” or “a land where the Thoo Lei flower can grow.” It is what the Karen people call their home state. The Burmese considered the Karen to be armed rebels, and the two forces had been battling ferociously since 1949. The fighting in Kaw Thoo Lei reached an especially fierce pitch in 1997, when Christina was only three years old. This is how Christina wrote about what happened in her “Autobiography”:

I lived in Burma for 3 years before I moved to Thailand. I moved to Thailand because the Burmese government treated us like animals and tried to kill us. Burma is a beautiful place but the government is dangerous. When I lived there I had to hide by the bush most of the time. When the Burmese government came to our village we had to hide because we knew that they are coming to kills us. On February 14, 1997 my family, my friends and other people we had to run and move to another country.

Prior to her arrival in the United States, all of Christina’s schooling had taken place in Tham Hin Camp. She lived in a makeshift hut of bamboo and tarpaulins. Her school had cinder block walls and a roof of corrugated tin. Christina had learned to read and write in Karen, Thai, Burmese, and English; Karen and Burmese use distinct but related alphabets, while Thai uses a different script altogether, and English uses the Latin script. She had learned to read and write while employing four different alphabets.

One teacher who grew fond of her nicknamed her “Silly One,” because although she showed up in her mandatory navy blue plaid skirt and short-sleeved white blouse, she invented her own idiosyncratic way of writing Burmese, which he alone spotted and teased her about. She would write Burmese sentences using the Karen alphabet, instead of employing the slightly different Burmese lettering. “He thought it was silly,” she said. “And he thought it was smart, too.” Writing Burmese the wrong way had been, for her, an act of resistance."I moved to Thailand because the Burmese government treated us like animals and tried to kill us."

tweet this

Contagious diseases plague the residents of refugee camps all over the world, and one of Christina’s most vivid memories concerns her bout with cerebral malaria. In the case of cerebral malaria, parasite-filled blood cells block the small blood vessels to the brain, causing swelling that can result in brain damage, coma, or death. Christina was mistaken for dead by medical staff after she entered a coma. Of this, she wrote:

I had to go to a Thai hospital and stayed about one month. When I was in the Thai hospital the doctor told my mom that there was no hope for me and then they put me in the place where dead people were put. My mom was very upset that the doctor had told her that I was no longer alive. After about 12 hours of being asleep, I woke up and I thought, “Where am I in the earth?” I saw a humans lying down with cloth covering their faces and then I started crying.

Meanwhile, Christina’s biological parents were not getting along. Their divorce resulted in the three girls being raised by their maternal grandmother. Christina’s grandmother applied for the family to resettle in the United States. Christina’s mother was listed on the application, but ultimately she decided not to accompany her older children to the United States, because by the time they were chosen she had remarried, and she would have had to leave behind her younger children.

On the eve of their departure, camp officials briefed Christina and her siblings and their grandmother. Posters named the four seasons they would experience in the United States and the items they would encounter during their trip there: airplane seat, seat belt, bathroom door lock, tray table. About her transition, Christina wrote:

When I heard that I would to come to Colorado I was scared and nervous. I was scared because people told me that in Colorado there were a lot of cowboys and no Karen peoples. On November 7th my grandma, sisters and I left the camps. I was very upset because I didn’t want to come at all but my sisters were looking forward to seeing a new place. I was sad to leave my mom.

I arrived in Denver the evening of November 7, 2007. Between that day and December 1, 2008, many, many things happened in my life. It was a very hard time.

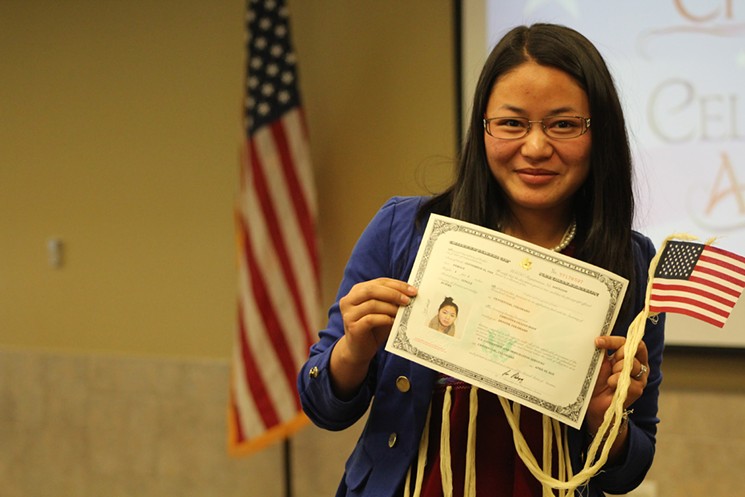

Christina (center) and her sisters celebrated Thanksgiving shortly after arriving in the United States.

Courtesy of Christina Hoff

One day, the young man her grandmother wanted her to marry had chased her all over the apartment building. To escape, Christina had jumped from a third-floor balcony. She landed wrong when she hit the parking lot, and hurt her arm. I could see why Christina’s favorite book in the world was Undaunted—I thought she was pretty undaunted herself, to risk injury rather than put up with the advances of a young man she did not want to sleep with.

Her grandmother would let him into their apartment late at night when he came home from work or from socializing with friends, and he used to wake Christina up and demand dinner, Christina said. Once, he had come into her bedroom and told her little sisters to go sleep in the living room, but instead of staying in the bedroom with him, Christina had gone to sleep in the living room, too.

We puzzled for a while over the mystery of what Christina’s grandmother had been thinking. We had no idea. Often, when Christina had made herself scarce to avoid having to spend time with her suitor, her grandmother had gone knocking on doors around the apartment building to search for her. Christina had hidden in various locations, including under the bed of her best friend.

At one point, her grandmother had tracked her down and had administered an especially severe beating during which she cut Christina’s right hand with a knife. Her grandmother had packed the wound with tobacco, a homemade remedy to stop bleeding. Almost exactly one year after her arrival in the United States, Christina showed up at middle school with a swollen right hand, unable to hold a pen. One of her teachers, a Bulgarian-born woman named Miss Petrova, asked why she could not take a math test. Christina said she had hurt her hand.

“What happened, Christina?” Miss Petrova had asked.

“It was an accident,” Christina replied.

“How did you do that?”

“I cut myself with a knife.”

“Christina, how could you cut yourself on your right hand, if you are right-handed? You have to tell me what really happened.”

That’s when Christina had made the enormous leap of trusting a Bulgarian-born, English-speaking woman whom she hardly knew. Her grandmother had cut her with a knife, she confessed. At that point, everything in Christina’s world turned upside down. Looking back on that moment from the vantage point of my car, parked beside her old building, after a total of eight years had elapsed, Christina said that Miss Petrova had saved her life. When I reached out to the teacher to confirm what had happened, Miss Petrova wrote to say that she kept a picture of Christina on her refrigerator to this day. “Not having any other relatives in the U.S., my students become my family,” she wrote. “Being an immigrant, just like them, I have a lot of empathy for them.”"There’s also trauma at the same time, and nobody at the school knows about it, and they’re navigating all of that."

tweet this

When they all went to see the school’s social worker, Christina’s two younger sisters became hysterical at the idea of being separated from their grandmother. The social worker explained that the girls were being taken to the city’s child welfare division. When a family’s worth of kids entered the foster care system, they usually did not remain together.

The social worker asked Christina if there was anybody she trusted, anybody she wanted to call. Christina answered, “Martha and Steve.” The couple had been visiting their apartment all year, bringing over used toys and used clothing. They had also invited the three Karen-speaking girls to their home on many occasions. Martha appeared within minutes, in Christina’s recollection. At the child welfare division of Denver Human Services, an employee told the frightened children they were about to go into foster care.

Martha said immediately, “They are not going anywhere but home with me.”

The city official looked appraisingly at Martha, and said, “I can make that happen.”

Growing accustomed to living with an American family was as momentous as a second resettlement. Martha and Steve went to extraordinary lengths to care for the girls; Steve moved out of the master bedroom for a while, and the couple put up a set of bunk beds, so that Christina’s sisters would have a place to sleep. Christina was offered a bed, too, but insisted on sleeping on the living room couch. She had gotten used to sleeping on couches while she had been trying to duck her grandmother’s wishes, and somehow the couch was more comforting. Eventually Martha and Steve built an addition onto the house so that there would be enough bedrooms for all seven children.

Martha and Steve wanted to do strange things like hug and ask how she was doing. “They are starting to creep me out,” Christina told her sisters. About that period in her life, which coincided with the second half of her eighth-grade school year and her start as a ninth-grader attending South High School, she wrote:

When I started my first year in high school I had lived with my new family for about eight months. It was really confusing and hard time for me at home. Whenever I came back from school I would stay in my room the whole time. I did whatever I wanted to do on the weekends...I wasn’t used to parents that expected to know where I was going and what I was doing. Being with two different cultures was really confusing, especially at first. Sometimes I needed help with my schoolwork and I was scared to tell my parents because I thought they would start yelling at me. But they don’t yell, they just always tell me if I need help tell them. Still, I was scared.

Learning English proved problematic for Christina. The languages she knew (Karen, Burmese, and Thai) were about as far from English in terms of their structure as any language in the world. Karen speakers did not indicate changes in time by conjugating verbs, for example; for a while, Christina would state something in the present tense and then throw in the word “yesterday.” The whole concept of a language that was not tonal perplexed her, and she struggled with words that ended in consonants, because in Karen, there are no hard consonants at the end of words. At first, Christina could not distinguish between words like “scarf” and “scar”—to her, they both sounded like “skah.” Gradually, however, her teachers helped her acclimate, both academically and socially. Meanwhile, Steve took the girls hiking and taught them how to talk through disagreements, and Martha offered emotional sanctuary. She let Christina tell her story, little by little, and as all was revealed, Martha showed Christina how to grieve. “My mom, she cries and cries!” Christina said, delighted to have found such a mother. Shortly after Christina turned eighteen, Steve and Martha formally adopted all three girls. It cost $180 to adopt Christina, because she was an adult; her sisters had cost even more.

“Mom, we are so expensive!” Christina had said to Martha.

Martha told her, “Money is nothing. We have the money. Life is more important.”

Martha and Steve had a tradition in their family, which they generously extended to the three new children they had suddenly acquired. After the children turned sixteen, they could take a trip anywhere they wanted to go in the world. When the trip occurred would depend upon the family finances, but it would happen. Christina asked to go back to Thailand. She wanted to see the refugee camp where she had grown up, find her mother, and reunite with old friends.

Steve took Christina to Thailand in December 2015. When she walked into her former school, her old teacher had taken one look at her face and said, “Silly One!” He remembered: She was the girl who would not write the right way in Burmese.

Seven months after her trip to Thailand, in August 2016, I visited South High on the first day of school and stumbled across Christina in a second floor hallway, looking professional in a sheath dress and a blazer. She brandished a plastic ID badge that she wore around her neck and declared proudly, “I’m working here now!”

Back when Christina had entered the school as a freshman, she had been placed into the classroom of an energetic young ELA teacher named Jen Hanson. Hanson had just become the new principal of South High, and one of her first acts had been to hire paraprofessionals who spoke a variety of languages commonly used in the building, including her former student, Christina, who spoke Karen, Thai, and Burmese.

Later, I observed Christina help in an upper-level E.L.A. classroom, where she chatted with Asian students in Thai, Burmese, and Karen. She also spent a fair amount of time teasing a young woman from El Salvador who persisted in speaking Spanish.

When a friend began translating for the El Salvadoran girl again, Christina walked over and said, “Speak English!”

“I have nerves when I speak English,” the girl told her, in nearly perfect English.

“That’s because you don’t speak English enough!” Christina chastised affectionately.

It had taken Christina eight years to get to the point where she could talk about all of this. She could not possibly have recounted her story back when she had only just arrived and was still trying to figure out how to stick a consonant on the end of a word, how to make nouns plural, and how to indicate that an event had happened in the past. She had fled her home village during warfare, watched an uncle die in a land mine explosion, moved into a refugee settlement, almost died of malaria, been separated from both of her parents, resettled in the United States, experienced domestic abuse, and almost been given away as a child bride. Those were the kinds of extreme experiences some of the newcomers had endured. I had sensed that some of the kids in Mr. Williams’s room needed to stay well taped, just like the boxes they had made with Miss Pauline, but I hadn’t fully appreciated exactly what some of the newcomers might have survived until Christina enlightened me. Getting to know her gave me a new level of respect for everyone in Room 142.

From The Newcomers: Finding Refuge, Friendship, and Hope in an American Classroom by Helen Thorpe. Copyright 2017 by Helen Thorpe; reprinted by permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Helen Thorpe will sign copies and talk about the book at 7 p.m. Tuesday, November 14, at the Boulder Public Library; at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, November 15, at Old Firehouse Books in Fort Collins; and at 7 p.m. Thursday, November 16, at the Tattered Cover, 2526 East Colfax Avenue. Find out more at 303-322-7727 or tatteredcover.com.

The author spent a year in room 142 at South High School to report what became her book, The Newcomers.

Westword