When Stone speaks between 3 and 7 p.m. weekdays on 103.5 The Fox, his unmistakable voice — gruff and gritty, yet sly — serves as a sort of aural time machine, transporting listeners back to the days when rock ruled local airwaves. There have been a load of changes on the media scene since he first hit town in 1990, including to him: The legendarily hard-partying lunatic and part-time rock wailer (in 2009, Westword named his group, Horse, Denver's best metal band) now abstains from most intoxicants, except for a little weed on occasion. But after layoffs, firings and career downturns that would have silenced a lesser talent, Stone is still delivering the goods on a daily basis both here and in Fort Collins, where he serves as the morning host at 92.9 The Bear.

That's not to mention the work Stone does for dozens of other radio outlets across the country via voice-tracking, a technique that allows him to record his work at a studio in his home and send it out to sticks (a slang term for stations) in towns big and small.

In the following Q&A, Stone details his journey from the Texas panhandle to the Mile High City, and his impressive run at KBPI, which, like the Fox, is part of the iHeartRadio empire

Here's the Uncle Nasty story:

Westword: Where are you from originally? Tell me a little about your family.

Gregg Stone: I was born back east. My dad did a bunch stuff for the government during Vietnam, so we lived all over the South Pacific. Moved back to New England in ’73 and then to Texas in late ’75, and then I moved here in ’90. Between ’90 and now, I lived in California for a couple of years — between ’94 and ’96 — and then in Salt Lake City from ’96 to ’98. And then I've been here ever since.

How many siblings do you have? And how did you first get into music?

I've got two sisters, and I'd say my older sister probably turned me on to rock and roll, plus my peer group. I'm from the generation that MTV introduced itself to, so we got glimpses of how crazy the rock-and-roll world was in the panhandle of Texas, and we lost our minds.

Did you immediately gravitate toward classic rock and the harder stuff?

Oh, yeah. You run the gamut. The Beatles, the Stones, Led Zeppelin, the Who — all those classic rock bands. But I was a huge Iron Maiden fan. I loved Iron Maiden, and still do. Maiden, Judas Priest, Van Halen — all that old David Lee Roth stuff was great. And Metallica. When Metallica was introduced to me, it was a game-changer. I was like, "I can identify with this."

How did you end up in the radio business? Did you target that early on?

I did. I was probably fourteen, fifteen years old when I started at a local radio station in the town that I grew up in. I went down there and told them I would sweep the floors, and they were like, "Hey, let's see how competent this kid is." Once they found out I could push buttons and follow instructions, I was running the place.

What was the format of the station?

It was adult-contemporary on the AM and satellite country on the FM, and I basically started doing football games on the weekends. Friday nights, I'd be doing my homework, and the play-by-play guy would say, "We'll be right back after this," and I'd pot them down, play the commercials, and then give them a countdown when we returned. That's what I did probably for the first three months, and then I started doing part-time stuff on the AM side. That led to filling in, and the rest is history, I guess. I was lucky to know what I wanted to do at an early age.

What were the call letters of the station?

KVOP — The Voice of Plainview.

Was your voice anything like it is now when you were fourteen?

Close. I came out this way! My mom was shocked and horrified! [Laughs.] No, I'm a former smoker; I quit in 2003. I lived kind of hard there for a while and sang in metal bands. It's got sort of a nice whiskey tone to it, I think. I've been sober for the most part. I don't drink or do narcotics. I haven't since 2005.

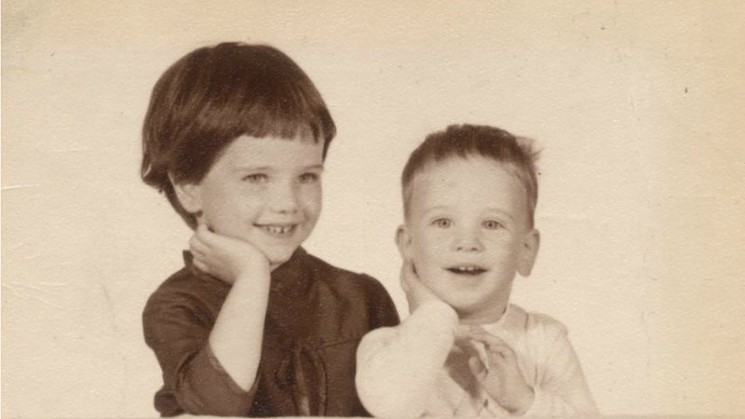

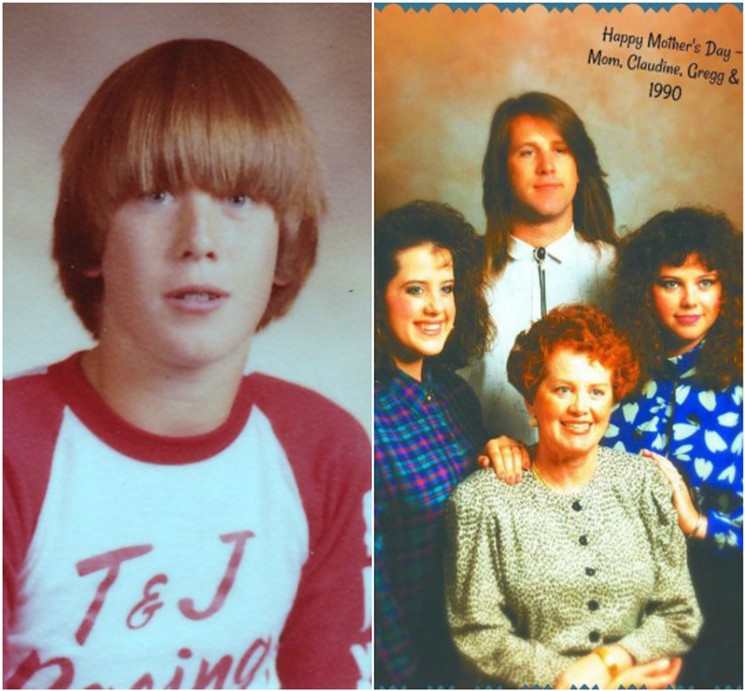

Gregg Stone during his bangin' teen years and in a family Christmas card from 1990, the year he joined KBPI.

Courtesy of Gregg Stone

I played trombone in middle-school band, and I guess I wasn't talented enough. But I've been singing since middle school with garage bands. I hit my peak with Horse. I'm really proud of that U.S. Metal record that we made. We were Westword's Best Metal Band in 2009. I'm really proud of that record and my bandmates Donnie Crisp, Doug Tackett and Steve Patt.

Did you know that your future was on the radio instead of on the stage? Or did you think you could do both?

I had passion for both, but I knew I excelled at the gift of gab. I knew that radio was going to be what I wanted to do. I liked the whole mystique of it, and I liked being on the inside. I liked having the opportunity to talk with everybody that my peer group looked up to. As fate would have it, my very first rock-star interview was with Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden, and I've never been so nervous in my freaking life. Still, to this day, I've never been that nervous. I could barely talk. He had to help me. He practically interviewed himself, I was so nervous.

What were some of the various stations you moved to after KVOP?

After I graduated from high school, I went to Husson University in Bangor, Maine, and went to the New England School of Broadcasting arm that they had. When I was up there, I interned for Stephen King's stereo station at the time. It was cool. I met him once. He would call the request line, and we were told by the program director to just say "Yes" and not play any of his requests [laughs].

He's a big hard-rock fan. He loves AC/DC, doesn't he?

Yeah, "Maximum Overdrive," that short story about trucks that was turned into a movie with Emilio Estevez — AC/DC did the soundtrack for that. After that, I went to another station in Bangor, Maine, WGUY, and then I came back to Texas and worked for KFMX, which was the rock station I grew up listening to in Lubbock, so it was cool. I did a couple of stints there. In fact, the first time I got fired was when I was doing overnights there.

Why did you get fired?

Well, you know: livin' like a rock star. It was about company policy, I believe. After that, I wandered around the Panhandle for a bit. Worked in Amarillo, worked in clubs. That's where radio guys did backup jobs for extra money: working in dance clubs or topless bars. I moved back to Lubbock and became music director at WFMX, the station that had fired me. Then I was at a Top 40 station, and I was developing this Uncle Nasty persona, although I didn't know it yet. The demo and what I wanted to create didn't gel, so I left that position and moved back to Amarillo and did the titty bar thing before I was hunted down by WFMX again.

How did you get to Denver?

This guy I worked with at WFMX came to Denver to apply for a job at KBCO, and while he was there, he heard there was an opening at KBPI. Bill Betts, KBPI's program director, said, "You're a little long in the tooth. We're looking for somebody a little more out of control." He thought that sounded like me, so I called Bill Betts, sent him some air checks, and he flew me down around Christmas of ’89. I moved to Denver in January of ’90.

How would you describe your show back then?

It was kind of like a madhouse — chaos that I tried to control. I was "Gregg Stone, your Uncle Nasty." When I went to Salt Lake, there was already a Gregg Stone, so the program director said, "Drop it. Just be Uncle Nasty." And I was — but now I'm back to being Gregg Stone.

I was in Denver for about six years when there was a merger between Great American and Jacor [the corporate precursor of Clear Channel and, later, iHeartRadio], and I wound up going to San Jose and working for KSJO for a couple of years. I was let go there, too, for not following company policy again; I had a real problem with that. [Laughs.] So I was "on the beat," a term we use in radio when you get fired and are looking for a job. But here comes Bill Betts, a guy who's come in and out of my life and helped me tremendously — helped me not just in radio, but helped me grow up and be a good man. He got me a job in Salt Lake at KBER that led to me doing a morning show and teaming up with Kelly Hammer, one of my favorite guys of all time. A great guy, a great family, a really good dude, a man of a thousand voices and a production wiz. We had a great morning show, and we were really cutting into Jacor's property there. So they wanted to hire me and send me somewhere else, and I had a couple of options: Denver and Detroit. My daughter lived in Denver, so I moved back here in ’98 and started doing afternoons for KBPI.

At the station, I picked up a great radio partner in Matt Need, and we did a lot of cool stuff — stuff that hadn't been done in radio for a long time. We resurrected old-style serial radio shows with a modern twist. And we were also the only friendly radio outlet that marijuana had back then. I think we had a lot to do with medical legalization. I was really surprised that Clear Channel locally never came down on me about it. I think we brought a lot of awareness and helped get rid of the stigma attached to marijuana by talking about it so freely and bringing in educated people, not just lay folks — people who had backgrounds in education and science. I think we had a lot to do with making marijuana so everyday.

Marijuana isn't for everybody, but for me, it really helped me with the anxiety of being sober — and when I say sober, I don't use narcotics, and I rarely use marijuana anymore. But I used to drink a lot, and I had a big cocaine habit. They were like chips and salsa for me. I had to stop, and marijuana made it a lot easier to deal with. I still had to do my job; I still had to go out. I couldn't tell my work, "I can't go to bars and concerts anymore." That's what I do. So I had to come up with a way to still do my job but also change my life, and marijuana helped me. Now we see lots of studies about how it helps with PTSD and a lot of other things. Marijuana is a gift, and it's all how you use things. But it helped me.

During that period, you were voice-tracking shows all over the country, right?

Yeah. In the early 2000s through the mid-2000s, I was doing Houston, San Diego, El Paso, Wichita, Kansas, back in the Bay Area on KSJO. Just all over the place. At one point, I had eleven different markets at the same time, which was kind of confusing and led to some polyp issues. I was talking ten to twelve hours a day and I had to cut back, but I got through it with the help of Dr. Dave Opperman and Buzz [Reifman] at the Colorado Voice Clinic. They've really helped me out not just with my vocal cords, but also my lifestyle. I've known Buzz since 1990. I met him the first summer I was up here, at Red Rocks, and when I first started having voice issues, I was still smoking and drinking. Now those are taken off the plate, but I still get scoped two or three times a year. I owe them a lot.

Now, Clear Channel has a different model for voice-tracking. But back then, I was paid five grand to twelve grand per station, depending on the size of the market, and that was good for me. But people like me took away a lot of medium-market jobs, and even smaller-market jobs.

Those people that weren't as successful as me at the time but who were doing a lot of small and medium markets, or medium and large: You're taking away those stepping stones for young talent, and I think that shows now. I think that's why I'm still here — because we didn't develop any new talent the way I came up. When I was starting, you had the opportunity to fail in a small market. You didn't just start in a large market doing promotion stuff, which is how most people start today. It's all voice-tracking. There are people on now who've never been live on the radio every day.

Another thing that changed radio in this period was the rise of the People Meter as the way ratings were determined.

It did. Ratings used to be based on diaries, where people would write down what they listened to — and if they had a favorite station, they might write down that they listened to the station all day. But the People Meter is this device that's run by Nielsen, the same people who do TV ratings, and it's like a pager. You get people to agree to be a People Meter carrier, people of different demographics, races, genders, ages, and it measures exposure — not necessarily what the listener wants to listen to, but what he's exposed to. You walk into a doctor's office and they have KOSI on, and that's what you're exposed to. You could leave in five minutes, but that still counts as you listening for a quarter-hour. And that's how us radio people live and die — by how many quarter-hours we have. The more you have, the better. You get time spent listening and the cume [cumulative audience], and that determines what your rank and market share are.

We thought People Meters were going to give us a more accurate interpretation of what people were listening to, because some groups were highly under-sampled, and we'd get different people to participate. But that turned into "Shut the fuck up, because we don't want to offend anybody and get them to punch out." Every week, when People Meters were in their infancy, we'd have meetings where they would tell us to talk less, and then they'd tell us to talk more, or they'd tell us, "They like it when you talk about this, so talk about this." Management didn't understand it — nobody really understood it — so there was all this knee-jerking, because the company wanted results, and the People Meter was killing all our sticks.

With the People Meter, you can actually see to the minute when people are tuning in or tuning out, and one time they said to me, "Everybody seems to be leaving your show at 5:45. What are you doing at 5:45?" And I said, "I'm not doing anything. They're puling into their driveway and turning off their cars at 5:45." And they looked at me and were like, "We didn't even think about that." But that's what happens. People between 25 and 54 are done with work and they're getting home at about 5:45.

What led to KBPI laying you off?

Clear Channel let me go in 2012 because they had this new policy where there was only going to be one highly compensated employee per stick, and I lost the game. After that, I worked at Jack FM for a while, and then I was let go there. That was Christmas of 2014.

Luckily, you had a lot of other voice work that you were doing, including for TV.

Yeah, I was the narrator for some shows. I did Storm Chasers for the Discovery Channel and Alaskan Bush Pilots for the Outdoor Network. I was like a segue; I helped the show move along and filled in the gaps. Now you hear a lot of people on reality shows doing that instead of a voiceover guy. The industry sort of changed there. But I also do stuff for Local Radio Networks. We're a format and content provider, which is something I've also done for ABC Radio. I help program classic rock and do afternoons on sixty classic-rock stations throughout the U.S. — mainly small and medium markets. And I do commercials for OmniVision and RadioVision. I do a lot of car commercials.

How did you find your way back to iHeart?

In 2016, my good friend and now-boss, Garner Goin, was running the show for 92.9 The Bear in Fort Collins, and he offered to make me program director up there and have me do the afternoon show. But for the amount of money that job paid, I couldn't justify taking my kids out of school and moving to Fort Collins. So I came up with an idea. I said to him that they could put in NexGen, the software iHeart uses in all of its properties, at my house, in my home studio — "so I won't be your program director, but I'll do the show for a lot less and work things out." It was a compromise they accepted, so that's what we did. They moved me to mornings in 2017, so I've been doing that for coming up on three years. And then Garner got hired to be the program director at the Fox, and he brought me along. I've got the NexGen softweare on all the PCs in my house, so I can tap into anything, and they can route me to anywhere in the world. Like if someone passes away on a weekend, I'm Uncle Obituary — the guy they call to do the obituary, do the update.

103.5 The Fox personalities Kathy Lee, Rick Lewis, Gregg Stone and Susie Wargin (from left) at a recent Broncos game.

Courtesy of Gregg Stone

I'm always voice-tracked, but I'm voice-tracked the day of, so you're getting current information. And I have the ability to do updates if something happens with traffic or weather or something political that isn't polarizing. If the U.S. intervened in a war or there was a massive natural disaster, I have the ability to go in and put in current, up-to-the-minute information. But I do it all from my house, in my own studio. And voice-tracking gives me the ability to do a lot of other things I like to do in my life. I like it in that aspect, but I also miss the spontaneity and the creativity of being live. There's a lot of fun in that.

That's only one of the many changes you've seen in how radio works.

Oh, yeah. To put it in perspective, when I started in radio, back in ’83, ’84, we were still cueing up records. I was around for the introduction of the compact disc. I worked for stations that had all their music on carts; they looked like an eight track, but it was a four-track, and you'd put them in these cart machines that looked like eight-track players. That's how most of the commercials were done back in the day. They were placed on these carts, and then you had to pull them and manually play them. I didn't see digital automation for a long time. In Salt Lake, we had a digital editor, but I think we were still pulling things, using CDs. But NexGen, which was originally called Prophet, was the first software I worked with that was all digitized. You didn't have to pull spots or music. It was all there.

Today, people keep saying that terrestrial radio is dead and that rock is dead. But you're proving that both of those statements are incorrect.

It's more than just me that's proving that. Rock is alive and well, and so is radio. But people always say things like that. When cable came in, it was supposed to be the death of network TV, and when satellite radio came along, that was it for terrestrial radio. But it turns out satellite radio repeats more than terrestrial radio does, and satellite can't provide that locality that people want. Drive time is huge: morning drive going to work or school, afternoon drive coming home. There's a statistic that 93 percent of Americans still listen to the radio every week. And if you're into sports, you're listening to sports-talk radio in your home town. So radio is still viable and people still like it. They like having that connection to people they know in their town. It helps them get through their day. And I think Denver is having a rock resurgence with new music and music from the ’80s and ’90s. I've never seen so many tribute bands available on a Friday or Saturday night, exposing people to music they never had a chance to see and helping a lot of young kids who are just developing see what was popular.

And you're still going strong.

I wouldn't be who I am and where I'm at without a lot of help. First of all, I want to thank the listening audience all these years, especially in Denver. They're a very loyal group of people, and one of the best compliments I can ever receive is when someone says, "I've been listening to you since I was a little kid." I've loved the fact that I've had that career and that staying power and that influence — hopefully more good than bad. I want to thank Bill Betts and [local programming veteran] Bob Richards and Garner Goin and Willie B and Matt Need and Kelly Hammer — people I've worked with over the years. I want to thank my ex-wife, who put up with a lot. And I want to thank all the people who loaned me money and gave me drugs [laughs]. Although I don't need the drugs anymore.