It was the summer of 1990. I had recently been appointed as the executive director of the Jefferson County Health Department. Jefferson County, metropolitan Denver’s gateway to the Rocky Mountains, contained the Rocky Flats Plant, the Department of Energy’s industrial site that made plutonium triggers for nuclear bombs. It had been a year since Operation Desert Glow, the raid on the Rocky Flats Plant by the FBI and the US Environmental Protection Agency. As the government official statutorily responsible for protecting the health of Jefferson County’s residents, I was trying to learn all I could about the nuclear weapons fabrication site and its potential impact on the health of the community.

I knew little about Rocky Flats when I took the job. I had dated a girl from Boulder in the late 1960s who had pointed it out to me one day as we drove by on US Highway 93. “That’s where they make atomic bombs,” she said. I couldn’t see anything of interest going on there. I had also heard about the antinuclear protesters who had picketed Rocky Flats. I thought it was ironic that they had not been able to surround the plant when they attempted to hold hands and form a human chain around it. That was about all I knew about Rocky Flats until I applied for the job in Jefferson County.

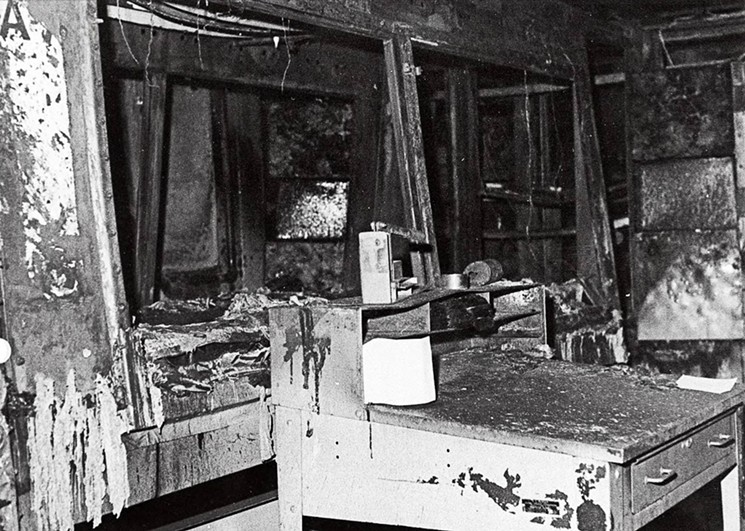

I subsequently learned that Rocky Flats was a very controversial place. In fact, Rocky Flats should never have been built. Its proximity upwind from a large population center, with prevailing winds moving in that direction, as well as its history of not-infrequent hurricane-force winds, should have disqualified the site before it was ever chosen. Allegedly, those assigned to find a site for an atomic bomb trigger facility used wind maps from Stapleton Airport, on the east side of Denver, instead of wind maps from Rocky Flats. Fires at the plant, as well as leakage from drums stored on site that were full of radioactive and hazardous waste, were known to have contaminated the site and the surrounding environs. The controversy was around how much contamination had taken place and how dangerous it might be. It still is.

I had read about some of the demonstrations that occurred in the 1970s, and I had seen pictures of some of the protesters sitting on the railroad tracks to stop the trains going in and out of the site. I also learned a bit about the FBI and EPA raid on Rocky Flats, one based on insiders’ claims that environmental crimes were being committed, but I knew nothing about the work that had been done there or the scope of the criminal activity being alleged. I knew there were growing concerns in the country about nuclear and hazardous waste contamination and disposal, but I was not aware how these might be affecting the health of the residents of Jefferson County — and the greater Denver area.

When I accepted the position in Jefferson County, my new administrative assistant asked me two questions before I officially began my duties: Would I be willing to review the county’s new policies on dealing with employees with AIDS, and would I like to have my name submitted to be on the Governor’s Health Advisory Panel, the task force being formed to look into the potential health impact of the situation at Rocky Flats? I said yes to both questions.

The next time we spoke, my assistant told me she had been informed by the Colorado Department of Health that membership of the Health Advisory Panel had already been determined, but I was welcome to attend their meetings as an observer. She then said something that I didn’t understand at the time. “They probably think you’re related to Carl Johnson.”

I had never heard of Carl Johnson.

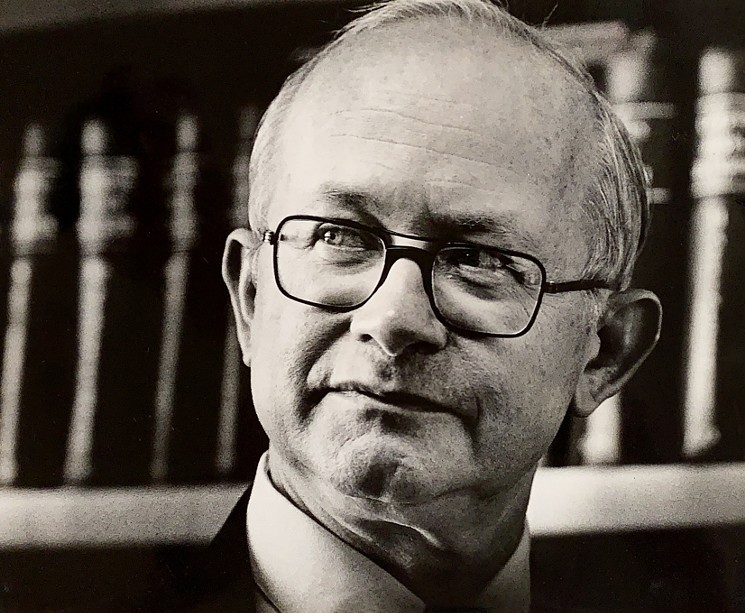

From 1973 until 1981 Dr. Carl J. Johnson (no relation) was the director of the Jefferson County Health Department, where he had had a very rocky tenure. In 1974 the chair of the County Commissioners asked his opinion about a proposal to rezone several square miles of ranchland near Rocky Flats for residential development. The request had already been approved by federal agencies and the Colorado Department of Health. After conferring with Dr. Edward Martell at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, Johnson recommended against the proposal. According to Dr. Martell, the soil in the area had been found to have plutonium contamination that was seven times higher than what was permitted by the state health department’s guidelines for construction workers’ exposure. Based in large part on Dr. Johnson’s recommendation, the commissioners did not approve the zoning permit request.

Carl Johnson went on to extensively study the contamination around Rocky Flats and its effects on the health of those living near it. Using cancer diagnosis data from the National Cancer Institute and plutonium exposures based on analysis of a group of soil samples collected in neighborhoods and ranches around Rocky Flats, he concluded that plutonium contamination of the soil around the plant was indeed very high and that numerous cancer types for persons living in exposed areas were much higher than expected when compared with control subjects living farther away. His studies also implicated the Rocky Flats Plant as the source of increased rates of malformations in the animals living near it.

In my first few months as the executive director of the Health Department, I read as many of Carl Johnson’s studies as I could find and learned much about his own tenure as the director. In 1981 he resigned in lieu of being fired by the Board of Health but subsequently sued them to be reinstated in his position. He was not reinstated but had finally been convinced to take what his attorney considered a generous monetary offer from the Board of Health to drop his claims. His lawsuits against the Jefferson County Board of Health and County Commissioners established several technical legal precedents for public health law in Colorado that are still widely referenced in the Colorado statutes. I would love to have talked to him about his experiences, but, unfortunately, he died in 1988, at the relatively young age of fifty-nine, from surgical complications for coronary heart disease.

I learned rather quickly that Rocky Flats was a major topic of conversation in Jefferson County. The recent raid on the plant and the subsequent media and legal interests had raised many questions about what it all meant for the county’s residents. In fact, during the first few months in my new job, I was asked to give several public presentations on Rocky Flats and its impact on the health of the community, so I needed to do a great deal of research to try to catch up with events. Almost everything I could find in the scientific literature supported the US federal agencies’ claims that very little contamination had occurred off the Rocky Flats site, and that there was no discernible increase in diseases related to exposure to Rocky Flats, other than some unique conditions among some of the plant’s workers. Carl Johnson’s work was severely criticized as having been produced by an amateur investigator with a political agenda, and statements were made asserting that recent, more sound research had invalidated his key findings. Hoping to get more information regarding his work and his history with the department, it seemed like a good idea to contact his wife.

It was not a good idea.

The woman with whom I had spoken on the telephone was Carl Johnson’s justifiably enraged widow. She clearly felt that her husband’s early demise was directly related to the stress he had suffered in his battles with the boards of Jefferson County. Her chilling and indignant response accentuated the tragedy through which she had lived. She well knew that her husband’s activities had enraged powerful political and commercial forces in Colorado, and that the state and federal governmental agencies had done what they could to portray him as a prototypical “enemy of the people.” She grieved that the reputation of her husband, who she knew was a good man, had been so badly tarnished.

The term “enemy of the people” has a long and storied past. It apparently originated in Roman times as hostis publicus, or “public enemy.” Shakespeare used it in the play Coriolanus as one common citizen’s description of a wealthy senator. The citizen claimed that if the mob would just kill the senator, who was an enemy of the people, they could have corn at their own price. The term has been used more recently by the Nazis in Germany, the leaders of the Soviet Union, and China, and as an epithet against the media by President Donald Trump.

Perhaps the most applicable use of the term for this chapter is found in Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 play entitled An Enemy of the People. The story plot may sound familiar. A public health physician discovers a source of contamination that he believes is of great danger to the health of the community. The source, however, provides the community with numerous well-paying jobs, an improving local economy, and an illustrious civic reputation.

While many in the community initially side with the physician in his quest to contain the pollution, over time, as more and more individuals realize what this will mean to their own personal prosperity, the community turns on him. For his honesty he is eventually persecuted, ridiculed, and declared an “enemy of the people” by the townspeople, including some of those who had originally been his closest allies. To those with whom I spoke in Jefferson County government, Carl Johnson had indeed been viewed as another enemy of the people.

In my quest to educate myself about Rocky Flats and the country’s nuclear program, I was soon reminded of some of the difficulties I had had in my college physics classes understanding the world of quantum mechanics.

Comprehending descriptions of nature at the smallest scale and the levels of energy held in atoms and subatomic particles had not come easily to me. Complicating things even further, not only is the way radioactive substances interact with objects and the human body complex, it seemed to me that the physicists who worked in this field had gone out of their way to make things as obscure as possible to the average person. I could begin to understand the differences between alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and x-rays and how they each have different effects on the human body, but the nomenclature used to describe their nature and activities was bewildering.

There are two major scientific classifications of measurements: English, or imperial, units and the International System of Units, or the Système International D’unités (SI). Measuring radiation in these two systems includes terms such as roentgens (R), coulombs/kilogram (C/kg), curies (Ci), becquerels (Bq), rads, grays (Gy), rems, sieverts (Sv), and disintegrations per minute. Because there is a move in the scientific community to replace one system with another, these terms are deliberately duplicative, but each conversion between systems has a different formula or conversion factor. Each system also has its own way of describing the special ways radioactivity moves, exposes things, and is absorbed by objects and beings. Unfortunately, some authors move back and forth between the systems in their writings, making things even more confusing. The mathematics involved in quantum physics is also incredibly challenging, traveling from the smallest of extremes in size to gigantic measures of energy.

In an attempt to make sense of it all, someone came up with the acronym “R-E-A-D.” The “R” stands for radioactivity, which is the ionized radiation released by a material, and is measured in curies (Ci) or becquerels (Bq). The “E” represents the exposure, which is the radiation traveling through the air, measured in roentgens (R) or coulombs/kilogram (C/kg). “A” is the absorbed dose, the radiation that is absorbed by an object or a person, measured in rads or grays (Gy). The “D” corresponds to the dose equivalent, the combined amount of radiation absorbed and the medical effects of that type of radiation. It is measured in rems and sieverts (Sv).

Explaining to most people what this means to them personally is almost impossible. Comparisons to the radiation exposure encountered during a medical procedure, such as a chest x-ray or a CT scan of the body, are often used. If you are exposed to 155 mrem (millirem), it’s like having a whole-body CT scan. If you are exposed to 155 sieverts, it is like getting 1,550,000 chest x-rays. More significantly, you’d be instantly vaporized. (This claim is widely debated by physicists on the internet, but for this purpose I think the term works.) This is the dose of radiation that hit the ground directly underneath the atomic blast at Hiroshima.

The reason we have systems of nomenclature is to simplify and stabilize the naming of objects to improve human communication. As a physician, however, I know this is not always the case. The language of medicine does, indeed, improve communication between medical clinicians, but it is also purposefully used at times to obscure things from patients, families, insurance companies, and the uninitiated. In my search to make sense out of radiation physics and quantum mechanics I became convinced that the same thing was being done by nuclear scientists to keep the rest of us in the dark.

Rocky Flats produced all of the plutonium triggers for the nation's nuclear arsenal.

Denver Public Library

The clandestine nature of the work at Rocky Flats could be justified — to a point. The Russians’ detonation of an atomic bomb in 1949 and a hydrogen bomb in 1955, along with their technological advances, as evidenced by the launching of the Sputnik satellite in 1957, sent shock waves through the US military establishment. The Cold War, with its race for a stockpile of atomic weapons, was on. Workers at Rocky Flats had every right to be proud of the historic labor in which they were involved. Initially, the drive to produce as many bomb triggers as possible as fast as possible had some degree of justification. Over time, however, as the contractors at Rocky Flats learned more and more about the dangers of contamination and the difficulty of hazardous and nuclear waste disposal, it seems to me that greed and fear of discovery overtook patriotism as the incentive for secrecy.

Over the years, I learned an increasing amount about the secrecy surrounding the nation’s nuclear program — including the mining, milling, testing, refining, and fabrication of the components for atomic weapons — and the obfuscation enveloping the storage and disposal of the nuclear and hazardous wastes that accumulate in these processes. As a result I came to believe that the government and its commercial contractors intentionally used both an unhealthy mix of patriotic zeal and the complexity of describing the work being done as a smokescreen to keep the uninitiated citizenry from knowing what was going on at Rocky Flats.

When I moved to Jefferson County, I felt I was open-minded regarding Rocky Flats and the nation’s nuclear weapons program. What I didn’t recognize at the time was that I brought and formed several significant biases and attitudes that influenced my approach to this issue.

I was pronuclear.

I grew up in Grand Junction, a city that used an atomic isotope symbol for a logo and was the commercial heart of the nuclear-industrial complex of the Colorado Plateau. Grand Junction had been a central part of the Manhattan Project’s secret effort to mine and refine domestic uranium. It was the home of the only domestic procurement program for uranium, and the site of a large uranium processing mill. While the parents of some of my classmates labored for the Union Mines Development Corporation, a front for Union Carbide’s classified work with uranium, and experimented on uranium milling and processing techniques for the United States Atomic Energy Commission, their children and I sat in classrooms, played on playgrounds, and golfed on golf courses built on radioactive uranium sand and soil — the “tailings” from the “yellowcake towns” that surrounded us.

We were proud of the role our town was playing in the Cold War against communism. It was only years later, when these friends and classmates began being diagnosed with cancer, and I found that I myself had a brain tumor, that I began to question the overall cost of growing up in “The City That Glows.”

I also grew up listening to my father’s stories of World War II. He was one of the soldiers scheduled to be among the first wave in the occupation of Japan in the summer of 1945. His unit had been told by their commanding officers that it was anticipated that a million American soldiers would die in the battles of the occupation. Numerous times during my childhood my father told me, “If it wasn’t for the atomic bomb, you never would have been born.” I was definitely pronuclear.

I was also progovernment.

That may not be the best way to describe this sentiment. It’s kind of a mixture of proscience, progovernment, and anticonspiracy theory. I had done my postgraduate medical studies in Baltimore, Maryland. Many of our lectures had been given by federal government scientists, and many field trips were taken to government facilities. Most of the research papers and studies we reviewed and dissected were written by scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, and several of my classmates went on to work for these federal institutions. I had also worked for the state health department in Wyoming and done elective rotations with the Colorado Department of Health. It had been my experience that both the federal and state health employees with whom I interacted were intelligent, serious scientists with great integrity, who believed in the scientific method and who were simply searching for fact-based evidence in their work.

I was skeptical of conspiracy theories, and my default position was to believe the government. I believed Oswald assassinated Kennedy and that the Warren Report was not a cover-up. I believed we had sent men to the moon. I did not believe the government was hiding UFOs and extraterrestrials at Area 51 in Nevada. I believed AIDS was caused by a natural virus, and that the CIA had had nothing to do with its manufacture or spread. I also believed that the USSR was a nuclear threat, that our stockpile of nuclear weapons was helping to deter World War III, and that our government would take good care of those who were working in these industries to protect us.

I soon became anti-Dr. Carl Johnson — at least for a while.

I am embarrassed to say this, but it is true. I had never met the man, but from my limited knowledge of his work in Jefferson County, I found myself siding with his critics. Many of those who had denounced his scientific work and methods were themselves, for the most part, credible physicists and nuclear scientists. Also, as I reviewed his work in Jefferson County, I tended to agree with those who felt he had focused too much attention on Rocky Flats and not enough time on the leading causes of death, disease, and disability in the county. It appeared to me that he had become consumed with Rocky Flats to the detriment of other important health issues such as tobacco-related diseases and the health impacts of other personal behaviors and lifestyle choices. It seemed he had neglected dealing with and preventing the negative consequences of important social determinants of health such as poverty, access to health care, education, health equity, and nonnuclear environmental factors.

I also have to admit that it hurt my professional pride to be constantly and negatively compared to Dr. Carl Johnson by his numerous devotees. Most of his detractors had moved on to other things, so almost all of the public appraisals contrasting him with me were from those who strongly admired him. Most of the comparisons cast me in a negative light. He had heroically battled the political and commercial powers that be. I was supporting a corrupt government-industry enterprise that was poisoning the environment. He was devoted to protecting the health of the residents of Jefferson County. I was only interested in protecting my job. He had invented an innovative new way of sampling dust for radioactivity. I had done…nothing. I got tired of hearing about Dr. Carl Johnson. I also determined that the legacy of my work in Jefferson County would not be related to Rocky Flats.

I found many of the antinuclear community advocates off-putting.

Probably due in large part to my knowledge limitations and the aforementioned biases, I found attendance at most public Rocky Flats meetings very unpleasant. I had been sheltered most of my life from the raw, aggressive, in-your-face approaches that many of the community advocates took in these deliberations. The open distrust of the Colorado Department of Health, the Department of Energy, and its Rocky Flats contractors was palpable and pervasive. The contentious, and often rude, accusations and allegations made me uncomfortable. The hostile and cynical view they displayed toward the scientific evidence was offensive to me as an epidemiologist. The lack of respect for authority seemed impertinent. Their behavior initially solidified my support for the government’s position.

Not all of my attitudes and biases, however, predisposed me toward supporting the work at Rocky Flats. I had an inherent suspicion of business and was wary of politicians.

Growing up in western Colorado, I had seen the ecological devastation that had been caused by a century of exploitation of our rich natural resources, mostly by eastern commercial interests. Although as children we loved exploring the old “ghost towns” that had been left behind by the nineteenth-century mining interests and collecting the rusty railroad spikes and whatever pieces of machinery we could carry away, it was obvious even to a child that great damage had been done to our environment. Later, as a history major in college, I learned that this was the dominant underlying theme of history in the American West — eastern commercial interests had always used their money and influence with the federal government to exploit and despoil western lands, peoples, and resources.

Public health as a discipline is also rather agnostic about business in general. While it recognizes the beneficial consequences of a robust economy on the health of populations, from its inception as a distinct field of endeavor it has been fighting with powerful but toxic trades. Beginning with battles against medical quacks and moving up to today’s campaigns against the tobacco industry, Big Pharma, and Big Alcohol, public health has had, and made, many powerful commercial adversaries. Conversely, because of its regulatory powers, it is also viewed with disdain and suspicion by many in business. Three popular movies around the turn of the century, A Civil Action (1998), The Insider (1999), and Erin Brockovich (2000), highlighted the mutual levels of distrust between public health and industry.

In addition, public health focuses on prevention, and prevention and politics are natural enemies. While prevention gets a great deal of public lip service, intervention and treatment get the funds. Politicians know instinctively that they need to be seen by their constituents as providing, or at least supporting, immediate, visible solutions. Such actions usually cannot wait for evidence-based data. Further, the impacts of prevention may take decades to be appreciated, while politicians are usually focused on the next election cycle. Politics also depends on public approval polls, whereas public health is often called upon to take unpopular positions.

The more time I spent conversing with politicians and contract managers from Rocky Flats, and the more I learned about the nuclear and hazardous waste pollution occurring around the plant, the more I came to question the underlying narrative that this was fundamentally a patriotic enterprise protecting America from its enemies. Gradually I came to view it as an industry that was greatly benefiting from the veil of secrecy and the apparently total level of liability indemnity that was being supplied to it by the DOE. Because of this screen of secrecy and an ultimate lack of accountability, it appeared to me that the Rocky Flats contractors had contaminated Jefferson County and its residents indiscriminately with no fear of consequences.

I attended as many of the various Rocky Flats committees and councils as I could work into my schedule, but I soon recognized an interesting pattern. I was welcome to attend, and at times even encouraged to participate in the deliberations, but decisions on the social and political issues about Rocky Flats were always passed on to the Board of County Commissioners and health matters were always assigned to the Colorado Department of Health. It was made clear, both explicitly and implicitly, that the Jefferson County Health Department had no role in the oversight of Rocky Flats. The legacy of Carl Johnson cast a long shadow.

To be fair, I can understand some of the reasoning behind this. The local health department in Jefferson County had no engineering or nuclear physics expertise and no funding with which to obtain any. The wisdom and the power clearly resided at the federal level. Even the state health department had limited resources in this area, and the more I watched the various community groups debate the situation at Rocky Flats, the more I became convinced that the DOE was making the ultimate decisions. Our department continued to monitor the activities, and often we had representatives at the community meetings, but we rather quickly began to focus our attention on other areas of public health in Jefferson County where it seemed that we could have more impact.

Analyzing any public health issue calls for viewing it under the lenses of what are called the core public health functions: assessment, assurance, and policy development. The assessment function calls for monitoring the environment to diagnose and investigate health problems and hazards in the community. Rocky Flats was clearly a potential health hazard to the community, but my own review and analysis of the various studies that had examined the health and disease rates of the surrounding population did not seem to support elevating it to the level of a major priority for departmental action. The crass way this is sometimes described is to ask, “Where are the bodies?” Although I subsequently came to doubt the veracity of much of the data we received regarding Rocky Flats, I trusted the information in the state’s cancer registry, and it did not seem to support the presence of a cancer cluster in those living near Rocky Flats, particularly those cancers most closely associated with exposure to plutonium.

Additionally, under the assurance function of public health, if another appropriate entity, such as the state health department, was actively addressing the potential hazard, our department could focus on other health issues in the community. Finally, it was made crystal clear to us by both the state and federal agencies involved that we were not going to play a role in the policy development surrounding the concerns identified at Rocky Flats. So, for many years of my tenure as the executive director, our department focused on preventing the environmental issues related to food service and clean air and water, and the leading causes of death, disability, and disease in Jefferson County, such as those associated with heart disease, stroke, tobacco-related diseases, obesity, and reproductive health.

Although our focus was elsewhere, Rocky Flats continued to weave its way into our work and consciousness. In 1996 we were funded by the DOE to conduct a community health assessment in Arvada with the University of Colorado’s School of Nursing. We were invited to have our Environmental Health team inspect their on-site canteen. We were also asked to review and share advice on the plans for a proposed water retention pond that was never completed. But for the most part, our department was minimally involved with the plans and cleanup activities going on at Rocky Flats.

Then in 2009 I received a telephone call from Colorado representative Wes McKinley. Representative McKinley was a cowboy and rancher from Baca County, Colorado, the county in the farthest southeast corner of the state.

Although we had never met, I had practiced medicine in Baca County for three years, and Wes and I knew each other by reputation. He had been the foreman on the Rocky Flats grand jury and was still very concerned about the community’s exposure to the plant, especially now that it was scheduled to be opened to the public as a national wildlife refuge. He was sponsoring a bill that required posting signs at the entrance to the refuge and wondered if I would be willing to testify in support of it. The signs needed to disclose to the public “information about the presence of, and risks posed by, plutonium and other toxic substances that were used in the production of nuclear weapons” at the site, which would be open for recreation. This seemed prudent, so I told him I would testify.

Before I testified, however, I wanted to know more about Wes McKinley’s experience on the grand jury. This led me to search for a copy of the book he had written with attorney Caron Balkany, The Ambushed Grand Jury: How the Justice Department Covered Up Government Nuclear Crimes and How We Caught Them Red Handed. I ended up having to order a copy of the book, but while searching for it in a used bookstore in Boulder, I ran across a copy of Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West, by Len Ackland. It was the reading of these two books that did the most to change my attitude toward Rocky Flats. They did not move me all the way into the antinuclear activist camp, but they made me reevaluate my stance and become much more skeptical of the official government position. Having now worked with and watched the DOE for several years, I was much more open to claims that they and the US Department of Justice had “conspired” to deceive us.

Representative McKinley’s bill was killed in committee, but as I recall, this was where I first met Jon Lipsky, the head agent in the FBI raid on Rocky Flats in 1989. I was struck by the fact that the two men who knew the most about the history of contamination on and around the Rocky Flats plant site were both zealous opponents of opening the refuge to public visitors. It gave me pause and made me wonder what they knew that the rest of us were prohibited by court order from learning.

On October 13, 2005, the site contractor at Rocky Flats declared cleanup of the site complete. Substantial on- and off-site contamination consisting of plutonium, beryllium, and other hazardous substances, along with unknown quantities and chemical configurations of plutonium remaining in the site’s piping and tanks, had made this one of the most significant and challenging nuclear weapons plant cleanups to date. A project that had originally been estimated by the DOE to take up to sixty-five years at a cost of $37 billion had been completed in fewer than ten years at a cost of $7 billion. Interestingly, this was the exact amount that Congress had appropriated for the cleanup. The Central Operating Unit, where most of the industrial buildings were located, was the only site on which remediation took place. It was still determined to be too contaminated for public access. The DOE Office of Legacy Management is responsible for the maintenance and long-term surveillance of this portion of the site.

Congress had approved the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge Act in 2001, allowing for the establishment of a wildlife refuge in the security buffer zone, or Peripheral Operating Unit, the approximately 8.2 square miles that surround the Central Operating Unit. In this area, as well as in the off-site areas around Rocky Flats, no cleanup activities took place. Plans were being made for designated refuge trails to be built here for year-round public hiking, biking, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and horseback riding.

After completion of the cleanup, the main concerns regarding the Rocky Flats history of contamination were twofold. The first had to do with opening the refuge to public travel. The second was the Jefferson County Parkway, a proposed highway to be built along the east side of the buffer zone to complete a transportation beltway around the Denver region.

In 2017 I was interviewed by a local television station about a bill in the legislature dealing with registration of naturopathic doctors. At the end of the interview, as the cameraman was tearing down and putting away his camera, the reporter asked if there were any big public health stories going on in Jefferson County about which he should be reporting. I mentioned that there was a lot of discussion about the school, residential, and commercial areas that were being built adjacent to the Rocky Flats refuge, particularly in light of the 2012 publication of Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats, written by Kristen Iversen, which had reported on “the government’s sustained attempt to conceal the effects of the toxic and radioactive waste released by Rocky Flats.” The reporter immediately told the cameraman to set up again, and we proceeded to do an interview about Rocky Flats and the encroaching neighborhoods.

During that interview the reporter asked me a question that has considerably changed my professional life.

“Would you buy a house or send your children to a school so close to Rocky Flats?” he asked. “I probably would not at this time, no,” I answered, making it clear that I was speaking for myself, not for our department or for the Jefferson County government.

Knowing that the interview would be on the evening news that night, I felt I should alert the Jefferson County Boards of Commissioners and Health that this would be broadcast and attempt to clarify for them my position regarding Rocky Flats and the growth of residential neighborhoods in the vicinity. My central position was that I had spoken in a personal capacity and not as a departmental or county representative; that from past experience and reputation I did not have a great deal of trust in the DOE or its contractors; I did not have the expertise, nor did I feel I had credible evidence on which to make a reliable determination as to how safe it was to live or work in that area; and I felt that all available data needed to be reviewed by independent experts.

To me, it was neither a bold nor a courageous statement, but it apparently fit into an important public narrative and gave solace to a great many people. I received numerous phone calls, e-mails and letters thanking me for being so forthright and daring. I also learned, however, that many people were now concerned about living in the area. I thought I had been rather circumspect and cautious. Whatever the case, I quickly learned that I now had many new friends and a great many new critics. To those critics, I, too, was now an enemy of the people.

One particularly harsh critique came from an opinion columnist in the Denver Post. I was labeled an alarmist and was accused of “undermining the credibility and professionalism of every scientist, technician, statistician, and epidemiologist, both federal and state, who worked on the cleanup at Rocky Flats.” I was labeled the “general of the scare brigade.” I was called “reckless” and “irresponsible,” in part for questioning the veracity of the Department of Energy, an agency that is responsible for 107 Superfund and cleanup sites around the country, including Rocky Flats, which was ranked as the most dangerous nuclear site in the country and which had two of the ten most contaminated buildings in America on its property. This is also the federal agency that hid its known off-site nuclear contamination from the public for more than a decade until it was forced by community testing to admit its pollution. To undermine credibility there must be a semblance of credibility already present.

It is uncontested by all involved that there has been a detectable level of nuclear contamination in both the refuge buffer zone and on the private property outside of the Rocky Flats reserve. What is still contested is how much contamination took place, how far the contamination spread, and what risk there is to the public from the contamination, both on- and off-site. The government agencies, including the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, present reams of data supporting their claim that the risk is low. Their studies state that there is less than a one in a million chance of getting cancer from exposure to the Rocky Flats refuge.

Community groups and antinuclear activists have also revealed credible science that supports their claim that the risk is not trivial. At least eleven studies have found plutonium contamination just east of the plant at levels hundreds of times greater than background radiation, and at least three epidemiological studies have found significantly increased rates of cancer near and downwind from the plant.

In the HBO miniseries on the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Valery Legasov, the first deputy director of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy, compares the uranium-235 atom to a bullet traveling nearly at the speed of light, “penetrating everything in its path. Wood, metal, concrete, flesh.” He states that each bullet is capable of damaging our genetic code and of bringing sickness, cancer, and death. “Most of them will not stop firing for a hundred years. Some of them will not stop for fifty thousand years.” Plutonium-239 atoms, which make up most of the nuclear contamination at and around Rocky Flats, are different in many ways from uranium atoms. Their most likely route of entry into the human body is through inhalation. But if inhaled, or ingested, they, too, are like bullets, capable of damaging our genetic code; bringing sickness, cancer, and death; and they, too, will not stop firing for thousands of years.

Some of those plutonium “bullets” will hit their mark. There will be cancer cases caused by Rocky Flats plutonium. I do not know how many cases there will be. If the government data is correct, there will be very few; if the community studies’ data are correct, there will be more than expected. With today’s current technology, we will never be able to prove how many cases there are. That may change. Already studies are under way to determine the source of radioactive materials in solid tumors.

I have called for an independent review of all the collected Rocky Flats data to determine where the risk lies. I have also called for the unsealing of the Rocky Flats grand jury report. I believe the public has the right to know what occurred at Rocky Flats, and what the risk may still be of recreating on or living near the refuge. As I wrote in my response to the Denver Post’s opinion piece, “Two of the men who have seen the most evidence concerning the level of contamination at Rocky Flats, the lead agent for the FBI raid and the foreman of the grand jury, continue to advocate for the prohibition of public access to the site. This gives me great pause.”

Enemies of the people may actually have the best interests of the community at heart.

This is an excerpt from Doom With a View: Historical and Cultural Contexts of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, edited by Kristen Iversen with E. Warren Perry and Shannon Perry, and published by Fulcrum. There will be a Zoom launch party for the book with many of the authors at 6 p.m. Friday, September 4; register here.