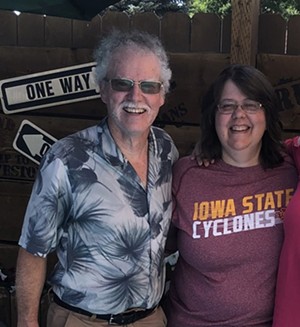

In August 2020, Cindy and Randy Looper received notice that they were facing a federal lawsuit over alleged violations of the Americans With Disabilities Act related to the Elk Run Inn, a motel they owned in Craig.

"Confusion and disbelief," says Cindy Looper, describing the feelings she and her husband had when they first learned they'd have to defend themselves against the claims in the U.S. District Court of Colorado. A plaintiff from Florida named Deborah Laufer had filed a complaint alleging that the Loopers didn't properly identify the accessibility of the motel, which typically caters to hunters and workers, on third-party reservation websites such as booking.com and hotels.com.

Title III of the ADA, which has been on the books since 1990, requires private businesses, including motels, to be fully accessible to people with disabilities. The complaint noted that Laufer has a disability and uses a wheelchair to get around. Owing to the "discriminatory conditions" of the online reservation system for the Elk Run Inn, Laufer "has suffered, and continues to suffer, frustration and humiliation," the complaint stated, adding that the Loopers were "depriving [Laufer] the equality of opportunity offered to the general public."

But both the Loopers and government officials in Craig maintain that the Elk Run Inn, a circa 1948, 23-room motel with a full kitchen in every room, is grandfathered into the ADA, which means that the Loopers have never needed to provide ADA-accessible accommodations. As they researched their accuser, the Loopers learned that Laufer had filed hundreds of other lawsuits making similar allegations across the country, including dozens in Colorado.

"[Laufer] is an advocate of the rights of similarly situated disabled persons and is a 'tester' for the purpose of asserting her civil rights and monitoring, ensuring, and determining whether places of public accommodation

and their websites are in compliance with the ADA," Laufer's initial complaint noted.

Laufer isn't the only "tester" who's filed hundreds of ADA complaints across the country. Such a practice is fairly standard for ADA Title III plaintiffs, much to the frustration of businesses that get hit with these charges. A June 2019 Westword cover story detailed how a Bailey restaurant owner was suing lawyers who'd originally sued him for alleged ADA violations; that lawsuit, which asserts that the ADA attorneys engaged in a criminal racket, remains ongoing.

"If it weren't for those people, those 'serial litigants,' every place would remain inaccessible to disabled people," says Tom Bacon, Laufer's Florida-based attorney. In fact, he adds, serial litigants like Laufer "see themselves as the person who wouldn't go to the back of the bus."

The rulings resulting from Laufer's lawsuits have been all over the map. Some cases have resulted in settlements for a few thousand dollars, while others have been less favorable for the plaintiff. In one federal court case in Maryland, a judge slammed Laufer for a lack of credibility.

"Plaintiff's approach to this ADA litigation appears to prioritize systematic, prolific filings over quality and depth of legal argument, churning out hundreds of near-identical lawsuits using cookie-cutter language irrespective of where the particular hotels are located, or any other party or jurisdiction-specific details," Judge Stephanie A. Gallagher of the U.S. District Court of Maryland wrote in a scathing December 2020 rebuke of Laufer and a Georgia lawyer representing her in that particular case. "Congress's intent in creating the ADA was to ensure that disabled individuals have equal access to public accommodations, not to facilitate the creation of litigation factories to allow attorneys to reap fees from hundreds of lawsuits while clogging the dockets of the federal courts. With that in mind, the Court warns Plaintiff and her counsel that future filings in her existing Maryland cases, and future lawsuits brought in the same vein while the impediments identified in this opinion persist, will be subject to close review for futility and frivolity, including the possible awarding of attorneys’ fees as sanctions."

Bacon, who was admonished in 2019 by a federal judge in Florida for not following court procedures in relation to ADA litigation, is also handling the appeal of that Maryland case. The judge "hates us," he says. "It was one of those circumstances where there could be no set of facts that the judge was going to let by."

Last month, Judge Nina Y. Wang of the U.S. District Court of Colorado ruled that Laufer lacked standing to sue the Loopers. "There are no allegations in the Complaint that Ms. Laufer had any intent to stay at [the motel] in the foreseeable future and that the lack of information regarding accessible rooms hindered her ability to do so," Wang wrote.

In November, Laufer had filed an affidavit related to her case in which she stated: "My niece lives in Colorado, I have visited her several times, and visit approximately once each year. I have plans to travel to there as soon as the Covid crisis is over and it is safe to travel. I intend to travel all throughout the State, and I need to stay in hotels when I go. Because the Defendant’s hotel and so many other hotel websites fail to allow for booking of accessible rooms and fail to provide sufficient information about whether or not the hotels’ features are accessible, it makes it extremely difficult for me to make any meaningful choice because I am deprived of the information I need to make my plans."

But Wang wasn't persuaded. "While Ms. Laufer indicates that her niece lives in Colorado, she does not indicate that her niece lives in proximity to Craig, Colorado, or she has any intention to visit Craig, Colorado as part of her 'travel all throughout the State.' The court further notes the striking similarity between Ms. Laufer’s Declaration offered in this action, and others — not as a test of credibility (which is not properly determined at the motion to dismiss stage) — but as further indicia that her alleged injury is not sufficiently particularized, concrete, or imminent," Wang wrote in her ruling on Laufer's lack of standing in the case.

"I do not want to diminish the fact that providing unequal information on the hotel website is a violation of the law, but it does — in my opinion based on current standing law requirements — easily fail to meet the requirement that the plaintiff must show a specific intent to return to the place of public accommodation or go to the place of public accommodation in the near future," says Kevin Williams, legal program director at the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition.

Williams holds legitimate ADA testers in high regard, viewing them on the same level as civil rights activists who sat at segregated lunch counters decades ago in order to force change. But "vague assertions of 'someday intentions' to go to a place or use a hotel are insufficient to pass the standing requirements," he explains.

Bacon has already filed a notice of appeal on behalf of Laufer in the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, stating that he disagrees with Wang's legal analysis. "The statutory subsections that apply to online reservation systems have no requirement that the plaintiff intend to do anything with that information," Bacon says.

The Loopers sold the Elk Run Inn in December, after putting it on the market three years ago. Since Laufer's complaint named them specifically, however, the couple still has to deal with the lawsuit.

"We can't let her get away with this," says Randy Looper. But at least the two won't have to break the bank to litigate this case.

Their attorney, Denver-based Stephen Rotter of The Workplace Counsel, stopped charging the Loopers a long time ago. "I only billed my clients for a few hours' work, and I did the rest of the work for free," Rotter says, adding that while he might get referrals from the case, he's representing the Loopers against Laufer's claim because he just doesn't "feel like it's right."

Rotter questions the motivations of both Laufer and the attorneys involved with her cases. In late 2020, he emailed other defense attorneys who had been defending lawsuits filed by Laufer; since then, they've shared information and ideas.

"Most defendants are settling for somewhere between $3,000 and $6,000," Rotter says, adding that he thinks Laufer and the attorneys suing on her behalf "know that the cost of litigating these is way higher than settling," which results in businesses agreeing to settle quickly.

While Bacon notes that Colorado ADA plaintiffs are entitled to a nominal amount of statutory damages in successful cases, they aren't in many other states. "People who are disabled usually get sick and tired of the fact that places are just not accessible to them," he says.

"We sue, we demand our fees, costs and litigation expenses. We're not making a million dollars," Bacon explains. "We have offered to settle these cases for scraps."

But so far, the Loopers aren't interested in settling. "We don't want to pay off extortionists," says Cindy.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]