“It’s night and day. It’s just incredible,” says Spellman, mayor of Black Hawk since 2006.

The hotel tower, 34 floors high, stands taller than the surrounding mountains.

The language of Amendment 4, the 1990 ballot initiative that proposed allowing legal gaming in the old Colorado mining towns of Black Hawk, Central City and Cripple Creek, was very specific regarding how structures where gaming was allowed should conform to “architectural styles and designs that were common to the areas prior to World War I.”

If someone wants to “split hairs,” Spellman is ready to explain how the Ameristar complies with that language. “The hotel doesn’t have any gaming. It doesn’t sit in the gaming district, so it doesn’t fall under —” Spellman stops, then quickly adds, “But I can’t tell you that with a straight face.”

Instead, Spellman points out that Amendment 4’s section on architectural styles included the stipulation “as determined by the respective municipal governing bodies.” In other words, Black Hawk officials can decree what is and isn’t pre-World War I architecture in their town, and they’ve adopted a very broad definition. “I firmly believe that had we not done this, all three host gaming cities would’ve lost out, because somebody bigger would’ve gotten gaming,” Spellman says, citing Aurora’s racetracks as potential competition.

Two days later, Jeremy Fey, who won his race to become mayor of Central City in November 2018, stands outside in his town one mile uphill from Black Hawk. He, too, considers the gaming industry to be important for the future of this historic town. But Fey has other dreams for Central City, dreams that could recapture the glory of the gold rush more than 160 years ago.

“I believe our greatest asset is our history,” Fey says. Playing off that history, he explains, Central City could grow from its current population of around 700 and become a “world-level destination for arts, entertainment and hospitality.”

The two mayors are as different as the towns they run, towns that have been historic rivals — sometimes friendly, sometimes not — for more than a century.“I believe our greatest asset is our history."

tweet this

The 48-year-old Fey, a son of legendary music promoter Barry Fey, is a newcomer in Central City. He and his wife, Aidarfa, who’s originally from Burkina Faso, moved from Denver to Central City in February 2017 so that Fey could focus on his goal of revitalizing the arts scene of a town that he had visited many times as a kid, only to see it lose its dynamism in recent years. He has visions of Central City once again becoming a boomtown, with 5,000 residents and a lively cultural scene.

Spellman is a 56-year-old, fifth-generation Black Hawk resident who has spent much of his life in local politics. He tries to keep Black Hawk’s population as low as possible so that the town can fully maximize the revenue it receives from gaming. “It would be more of a burden than a benefit,” Spellman says of a growing population. “It would not add to the tax base, but it would certainly be a strain on city revenues.” He notes that right now, residents get “free water, free trash service. We paint the homes once every eight years.” If more people lived in Black Hawk, that might not be possible.

In Spellman’s eyes, the sky’s the limit for gaming in Black Hawk, both literally and figuratively: He wants to pull in the Denver crowd that typically flies to Las Vegas for gambling.

Although their visions differ, the two mayors each have big plans for their towns, which are both fiercely independent and inextricably linked by history and geography.

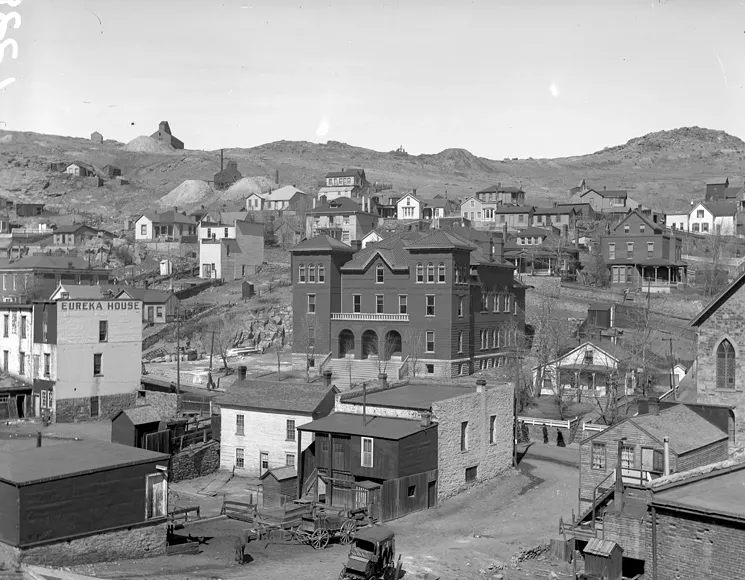

Central City became a cultural and economic center for Colorado.

Denver Public Library Special Collections

In 1860, the Black Hawk Quartz Mill Company built a metal-extraction facility on flat land down the mountain from Central City, in the area that became Black Hawk.

Central City soon became known as the “Richest Square Mile on Earth.” Residents established churches and schools to balance the saloons that had sprung up; Henry Teller, who became a senator after Colorado became a state in 1876, set up a law office, and “Aunt” Clara Brown, a former slave, started the laundry business that would make her rich. As History Colorado notes on its website, “There is hardly a more unlikely location for the establishment of a ‘boomtown’ than the rugged and inhospitable terrain of the surrounding mountainsides.”

On April 12, 1864, three years after Denver became the first city in Colorado to be incorporated, Black Hawk became the second. A few hours later, Central City became the third.

The Colorado Central Railroad came to Black Hawk in 1872, during Gilpin County’s most prosperous decade ever. In 1878, the 750-seat Central City Opera House was constructed, cementing Central City’s status as both a cultural and an economic center. Meanwhile, with the advent of new metal-extraction technology, Black Hawk developed into a working-class town complete with smelters that stunk up the air.

“There were entirely two different kinds of economy, two different kinds of residents,” says Jack Hidahl, who moved to Central City in 1972.

By the turn of the last century, though, as the mines played out, both towns began to fall on hard times — and stayed there. Their combined populations dropped from 4,314 in 1900 to 805 in 1920.

As Spellman says of Black Hawk, “The Great Depression started earlier and ended later.”

Black Hawk started out as a milling town, just a mile down the mountain from Central City

Denver Public Library Special Collections

The area had another, unofficial economic driver: gambling. The Smaldone family, Denver’s crime syndicate, ran a gambling operation in Central City from 1947 through 1949, according to Dick Kreck, author of Smaldone: The Untold Story of an American Crime Family. “Operating out of a single small casino grandly named Monte Carlo in a storefront across Eureka Street from the opera house, the Smaldones offered craps, roulette, and slot machines to eager visitors,” he writes. At the same time, a Central City resident operated slot machines and, “like the Smaldones, returned a portion of the take to civic improvements,” according to Kreck; social clubs also “provided slot machines to members.”

For a time, local law enforcement authorities allowed these operations to continue. By the ’50s, however, gambling was largely gone.

By the time Bruce Schmalz moved his family from Lakewood to Central City in 1972, both Black Hawk and Central City were dealing with aging infrastructure and few revenue sources. Buddy Schmalz started the second grade at Clark Elementary School, which served both Central City and Black Hawk, and quickly became friends with a fellow named Davey Spellman from Black Hawk.“We were in bad, bad shape, so some of us got to thinking that maybe there was a solution.”

tweet this

Bruce Schmalz took over the rock shop that his parents had opened in 1958, which catered to the summer tourist crowd, but as ski areas began to develop into year-round destinations, visitors to Gilpin County dropped off.

“We were in bad, bad shape, so some of us got to thinking that maybe there was a solution in expanding tourist appeal by creating gambling,” recalls Hidahl, who was the city administrator in the late ’80s when Central City got serious about legalizing gambling. “The idea was something like a couple of slot machines in the back of a gift shop.”

Bruce Schmalz, by now the mayor of Central City, got together with Hidahl and some other residents at the local Elks Lodge for what turned out to be a fateful series of meetings. They came up with a plan to push a ballot initiative that would allow for limited-stakes gaming in historic areas of Central City, modeling the idea after Deadwood, South Dakota, which had recently approved a limited-stakes setup rather than the high-stakes gambling scene of Las Vegas.

A group in Cripple Creek, an old mining town in Teller County west of Colorado Springs that had fallen on hard times, was in the process of hatching a similar plan.

Black Hawk wasn’t part of the deal at the start, according to Buddy Schmalz. But David Spellman remembers it differently.

“We had a meeting with Central City,” he recalls, “and what we said was, ‘We can either pursue this together or we can pursue this separately, but we are going to pursue it.’ So Central wasn’t appreciative of that, but so it was really Black Hawk and Central that started the process. Then a number of other cities tried to join in, and Cripple Creek was the only one that really brought money to the table.”

No matter how the three towns came together, Schmalz concedes, “They collectively got on board with this idea of ‘singly we’ll fail, collectively we might pass.’”

The three mountain towns first tried the legislative route, but failed to make any headway with a bill in the Colorado General Assembly. Then, with the help of powerful lobbyist Freda Poundstone, they decided to push legalized gambling as a preservation effort, and landed Amendment 4 on the November 1990 ballot.

Amendment 4 called for allowing “limited stakes gaming” in the three towns, with $5 maximum bets. The only games allowed would be blackjack, poker and slot machines, between 8 a.m. and 2 a.m. The measure also included specific language about restricting gambling to certain gaming districts and requiring all gaming establishments to have architectural designs that were common to the towns from 1875 to World War I.

The proposal also laid out a clear financial arrangement: The state could tax casinos up to 40 percent. At the end of the year, after paying for administrative expenses, the state would keep 50 percent of those taxes for its general fund, then send 28 percent to the state historical fund for preservation efforts, 12 percent to Gilpin and Teller counties, and 10 percent to Central City, Black Hawk and Cripple Creek. The amount given to the counties and towns would align with the percentage of gaming revenues generated in each town.

While the proposal was pitched as a way not only to save the failing mountain towns but also to fund historic preservation across the state, there was big money at play. “The issue of community decline had been invoked to promote the pro-gaming cause, but the relatively large sums donated by small businesses in the Gilpin County towns suggests that at least some local shop owners were not in a situation of imminent demise,” Patricia Stokowski, a professor at the University of Vermont, says in her 1996 book Riches and Regrets: Betting on Gambling in Two Colorado Mountain Towns.

Meanwhile, she writes, opposition was weak, underfunded and disorganized, with perhaps the most significant contribution against Amendment 4 coming in the form of around $22,000 in donations from Colorado racetrack stakeholders.“We determined that we wanted to become even more than just the premier gaming city.”

tweet this

Governor Roy Romer, who was running for a second term on the same ballot, opposed the initiative. “Romer knew that it wasn’t just going to be ma-and-pa, but that it would be large-scale gaming, as it is now, and that would take over and change the character of what people voted for,” recalls Mike Stratton, a political consultant who served as campaign manager for Romer.

Amendment 4 passed overwhelmingly, with 57.31 percent of Coloradans voting in favor of it.

The measure called for legal gambling to begin on October 1, 1991, in all three towns.

At first it seemed like Black Hawk would be bringing up the rear behind the tourist towns of Cripple Creek and Central City. “We had the least name recognition, the most anemic budget and the poorest infrastructure,” remembers Spellman, who was on the Black Hawk City Council at the time. In fact, when Amendment 4 passed, Black Hawk had a general-fund budget of just $109,650 a year and a water-fund budget of $51,129. But it had a few other assets, including a location right on highway 119, a mile closer to Denver than Central City.

On opening day, Black Hawk had two operational casinos; Central City had five. In fiscal year 1992, the first that included gaming, Black Hawk’s casinos collected $27.8 million, while Central City’s casinos accounted for $41.7 million in revenues. But that was the last time Black Hawk would be in second place.

Central City took a conservative approach to gaming-related developments.

“The purpose was for historic preservation — that this would provide enough revenue to not only take care of some crumbling infrastructure, but also some crumbling buildings, and also save buildings that contribute to the national historic landmark. And that would be the benefit to the state,” recalls Hidahl.

But gaming interests pushed hard for a liberal interpretation of Amendment 4’s language regarding percentage of a building that could be devoted to gaming, and state regulators ended up agreeing.

Concerned that things could get out of hand as developers kept pushing Central City, that town’s council took a drastic step: In April 1992, it passed a moratorium on accepting new gaming license applications. And Black Hawk took full advantage of that move.

“Our concerns about running out of infrastructure were very real,” remembers Hidahl, who supported the moratorium and wound up losing his job when council decided not to renew his contract. “When we went into the moratorium, individuals in Black Hawk said, ‘We don’t have any of those foolish regulations. Y’all come on down.’”

Although the moratorium lasted less than a year and was repealed in February 1993, it had a profound effect on Gilpin County’s gambling scene. Because while Central City was pulling back, Black Hawk was really letting it rip.

In fiscal year 1993, Black Hawk casino revenues jumped to $84.6 million, compared to $79.3 million for Central City. In fiscal year 2001, Black Hawk casinos racked up an amazing $453.6 million in revenues, compared to Central City’s take of just $60.4 million.

“We determined that we wanted to become even more than just the premier gaming city. We wanted to become a regional gaming-centric resort destination. So we encouraged these casinos to build...so we could meet the desires of the gaming public,” says Spellman. “This was by design; this was not the gaming industry running Black Hawk. It was Black Hawk telling those companies that came here what we wanted out of them and from them.”

What Black Hawk wanted was bigger and taller. Historic buildings — including the legendary Lace House — were moved to accommodate developments. Mountains were moved, too, particularly for the construction of the Ameristar tower — at one point the tallest building between the Colorado foothills and Salt Lake City. “The First Interstate Bank building in Salt Lake City, was, I don’t know, thirteen feet taller, and I said at the time, ‘Had I known that, I would have at a minimum made them put on a mooring station so that it could’ve been the tallest building between here and Las Vegas,” Spellman says.

And casinos in Black Hawk just continue to get bigger.

“Because Black Hawk was historically the ‘city of mills,’ a decision was made to allow gaming construction ‘in the style of’ the old ore-crushing mills,” explains Stokowski. “This opened the door for demolition of several old buildings and the construction of very large, new casinos.”

Some developers got lucky breaks, she suggests in her book: “On several occasions, usually when approval from the local historic review board was not forthcoming in a timely fashion, buildings tended to fall down unexpectedly.”

“My angst with Black Hawk right now is just with their willful violation of the intent of the gambling and reaping the profits of building things like 32-story ‘historic’ buildings,” says Hidahl, who recently finished a term on the Central City Council.

“Any other comments or criticisms from outside parties is just idle and bitter chatter,” counters Spellman.

Certainly the state never really challenged Black Hawk’s very liberal interpretation of what was appropriate architecture.

Colorado has collected over $2.5 billion in gambling-tax revenue since gaming became legal, with over $2 billion of those dollars coming from Black Hawk. In fiscal year 2019, Black Hawk casinos pulled in $619 million in revenue, while Central City accounted for just $79.8 million.

The two towns have gotten into some ugly squabbles over the years. For example, in the early 2000s, when Buddy Schmalz was serving as mayor of Central City, Black Hawk opposed Central City’s plan to build a road from I-70 to its casino district that would bypass Black Hawk altogether. But the Central City Parkway went through, and Schmalz dedicated it in 2004.

More recently, Black Hawk and Central City got into a legal dispute over land and a huge Black Hawk distillery project. In March 2020, Central City sued Black Hawk over a proposal by Proximo, the company that owns Stranahan’s, to construct a Tin Cup whiskey distillery resort. The crux of the suit was that Black Hawk would be violating a governmental agreement over land use if Black Hawk allowed the project to move forward.

After a verbal battle that included Spellman referring to the lawsuit as a “transparent” move by Central City to “extort financial gain,” the two sides were able to settle their differences late last year. The whiskey distillery resort is moving forward, though the timetable is uncertain.

But while there’s been plenty of bad blood spilled, the two cities are also linked by blood. Buddy Schmalz’s sister CinDee married Mark Spellman, David’s brother, in 1983. And David Spellman served as best man in Buddy Schmalz’s wedding.

The ties go further. David Spellman is married to Lynnette Hailey, who served as city manager of Black Hawk from 1995 to 1999, then moved on to become manager of Central City from 2003 to 2010.

There has been business cooperation, as well. When Buddy Schmalz was mayor, Black Hawk and Central City created a joint tourism bureau and a shared shuttle service, which continues to connect the towns today.

Jeremy Fey, who’d grown up in Denver as the son of promoter Barry Fey, definitely saw potential for bringing tourists back to Central City. In 2018, he resurrected the Central City Jazz Festival, which had originally run from the late ’70s until 1991, when casino construction filled the streets.

Through his work on the festival, he became intimately familiar with Central City politics. “I started booking in fall 2017,” he recalls. “I came to every council and committee meeting.”

The festival was in June 2018, and “it was wonderful,” says Fey. “It gave credibility to anything I was saying to the locals.” So much credibility, in fact, that in November 2018, when Fey ran for mayor against incumbent Kathy Heider — campaigning around town in a sandwich board sign encouraging locals to chat with him — Fey won by seven votes out of the 250 or so cast.

“I’ve had moments where I thought I should not have run. I hurt some feelings,” admits Fey, who says he likes Heider, a longtime resident.

But as mayor, Fey can push more of his grand ideas for Central City.

“If you’re anywhere in Colorado and you’re like, ‘What should I do this weekend?’ I want you to know that you can always come to Central City and there will be a mic on somewhere, there will be a symposium somewhere, there will be an exhibition,” he predicts. “Some sort of an artistic endeavor that is customer-facing. And when I say always, I’m saying 24/7. We have 24/7 rules here because of gaming and everything else.”

Fey wants to host a festival every weekend possible. “I have purchased domain names for every genre: Central Jazz, Central Rock, Central Faith,” he says. He wants to fill not just the streets with action, but the opera house, too.

In 2018, the Central City Opera Association organized its first Plein Air Festival, an annual event that has artists painting fall landscapes and historic architecture of Central City while members of the public watch them at their craft — and then buy the paintings, after dropping more money around town. “It’s my favorite thing that goes on here,” says Fey.“I’ve had moments where I thought I should not have run. I hurt some feelings.”

tweet this

Fey doesn’t want to just draw tourists and art lovers to town. He wants to attract many more residents, too, turning unoccupied second floors above currently unoccupied retail floors into residential units, and transforming vacation homes or rentals into year-round residences. In fact, Fey is aiming for a full-time population of 5,000 to push “residential growth as it helps facilitate a vibrant economy,” he says.

“If you live here, you’re both part of the labor force and a potential customer to the businesses,” Fey explains.

Schmalz, who with his two sisters runs Dostal Alley, a brewpub and mini-casino in the building that once housed the family rock shop, has high praise for Fey. “Jeremy worked as hard as I’ve seen anyone work for a position out here,” he says.

But he says he’s “a little concerned about some of [Fey’s] crazy ideas,” like having 5,000 people in Central City.

Even if Fey does have the drive to achieve his goals, he’ll be term-limited after eight years in office, Schmalz notes, and might not be able to finish what he’s set out to accomplish.

The pandemic has certainly set back Fey’s timeline, and also made a massive dent in the revenue of Central City.

Black Hawk has suffered, too. As the Wall Street Journal noted in April 2020, Gilpin County posted “the nation’s biggest drop in output” — 70 percent — because of COVID-related shutdowns. But Spellman has more time to see his vision through: Black Hawk residents did away with term limits in 2003.

“At that time, as we do now, the city had a highly dedicated group of core citizens who were true believers in the future of Black Hawk, and the residents agreed, knowing that every four years they had an opportunity to make a change in leadership if they so desired,” says Spellman, who hasn’t faced an opponent since his first mayoral race.

Elected officials in Black Hawk have “built an empire,” Schmalz says. City council meetings happen in the blink of an eye because all of the votes are unanimous. And the local newspaper isn’t critical of those actions; in 2009 Spellman bought the Weekly Register Call, Colorado’s oldest newspaper, founded in Central City shortly after the discovery of gold.

Black Hawk’s annual budget before gaming was about $160,000; before COVID hit, 2020’s budget was projected at over $26 million. In 2019, the City of Black Hawk generated over $8 million in device-fee revenue and received over $8.4 million from the state gaming fund.

Even so, Spellman says, “Our ambitions outpace our revenue.”

Colorado’s evolving gambling industry has allowed those ambitions to grow.

Although other municipalities’ attempts to legalize gaming have failed, the rules keep becoming looser in the three towns where it is allowed.

In 2008, Colorado voters approved raising the stakes to $100, allowing casinos to add craps and roulette, and giving them the greenlight to operate around the clock. Like Amendment 4, which was touted as benefiting historic preservation, Amendment 50 had an attractive beneficiary: Most of the new tax revenue would go to financial aid and classroom instruction at Colorado community colleges.

According to Chris Bowles, director of Preservation Incentives Programs and deputy State Historic Preservation officer, “Colorado wouldn’t be anywhere in terms of its preservation efforts without gaming.” Most of the $315 million granted so far has gone to “fixing up old Victorian houses,” he says, though the funding has recently shifted its focus to helping smaller, underrepresented communities.

In November 2019, Colorado voters legalized sports gambling. A vast majority of the tax revenue from that measure was earmarked for the Colorado Water Plan. And this past November, Colorado voters completely lifted the limits on the three casino towns, allowing them to make their own rules on the size of bets and the games allowed.“Colorado wouldn’t be anywhere in terms of its preservation efforts without gaming.”

tweet this

Not only did the majority of voters in both Black Hawk and Central City support Amendment 77 on election night, but in December, the city councils in both towns approved removing any gambling bet limits in Black Hawk and Central City as of May 1, 2021.

The recent developments have been positive, Spellman and Fey agree. While sports wagering is dominated by mobile apps, casino operators are betting on fans coming up to the gambling towns to watch major sporting events. And with bet limits raised, Fey suggests, bigger names in the gaming industry are starting to view both cities as hotter destinations.

“We have a very healthy gaming aspect to our economy up here, but after that, it’s really just thrift stores and pot shops, none of which would be here if it weren’t for gaming,” says Fey, who wants to diversify the economy.

Spellman, meanwhile, is focusing on extending the amount of time people spend in Black Hawk; he wants not just day visitors, but gamblers who will spend several nights in Black Hawk, choosing the mountain town over Las Vegas. “We actually play the national anthem three times a day on our caroling chimes,” he says. “Black Hawk has always been a patriotic city. With all the America-bashing, that’s where we’re at.”

He’s been impressed by what the Farahi family, which already operated a casino in Reno, has been able to do with the Monarch, the former Riviera Black Hawk that they took over in 2012.

“I think the Farahi family really do appreciate our vision of Black Hawk when we’re telling the gaming industry, ‘You’re not adding enough. You’re not building enough amenities for what we want to achieve as a gaming-centric resort destination,’” Spellman says.

“We fully support the city’s vision of gaming just being one form of entertainment that visitors can enjoy when they come up here,” notes David Farahi, chief operating officer of the Monarch. “We want to help the city deliver its vision of having other things to do. Whether it’s outdoor recreation with the paths that they’re building up in the mountains or the distillers’ row vision that they have, we think it’s all great.”

The Monarch, which visitors see as soon as they drive into Black Hawk, just unveiled a massive expansion that includes a spa, which Farahi wants to be the best in Colorado.

“Our spa in Reno is rated a top-ten casino spa in the world,” Farahi says, adding that the Monarch spa could change the Front Range perception that Black Hawk is just about gambling.

“I think we’ve already come a long way in the last decade in changing that perception. The next decade will be even more transformational,” he says. “Right now [the Monarch has] three restaurants open and is opening a fourth in the not-too-distant future. We know we’ve accomplished our goal when people say, ‘I’m going up to Black Hawk to eat at a great restaurant and maybe gamble.’”

And then maybe even head up the hill to Central City for a cultural festival hosted by Mayor Fey?

“I like Jeremy,” Spellman says. “I think Jeremy is an asset to the City of Central. I think he breathes new life into the City of Central.”

Fey appreciates what Spellman has done, too. In fact, he reaches out to him not just to coordinate efforts between the towns, but to gain from Spellman’s experience. “There is this past history that is not healthy, and I am definitely conscious of it. But I don’t honor it, and I am actively trying to dissolve it,” he says. “He’s like a fifth-generation member of this community. Who would I be, coming in four years ago, not to rely on him for some wisdom? I call on him often.”

Still, bet on the two towns to continue their healthy competition. “I would always say that it is competitive, and that’s why these two cities have survived,” Spellman concludes. “One wasn’t going to give up if the other didn’t.”