There are government agencies that help protect the mammals at the aquarium, such as the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which oversees worker health and safety; the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, which inspects the facility to ensure food safety for diners; and the United States Department of Agriculture, which licenses the facility for its tigers and otters. But no government entity watches over the fish...unless they land on a plate.

“The biggest problem is that we’re a restaurant with an aquarium attached, not the other way around,” says one employee.

Westword spoke with a half-dozen aquarium employees regarding their concerns about the facility; all asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation by management, but they supplied images and documents to back up their statements.

The Downtown Aquarium has been owned by Landry’s, a Texas restaurant company headed by Tilman Fertitta, since 2003, when Landry’s bought what was originally known as Colorado’s Ocean Journey. Landry’s did not respond to numerous requests for an interview. But things don’t seem to be going swimmingly.

The Downtown Aquarium, which got its starts as Colorado's Ocean Journey, sits next to the South Platte River.

Stilfehler at Wikivoyage

In 1999, Colorado’s Ocean Journey debuted in a brand-new facility on the southwest side of the South Platte River near the Children’s Museum. A path through the aquarium began with the Colorado River exhibit and concluded with a display modeled after the Sea of Cortez, which is where the Colorado River meets the ocean in Mexico. Another path was modeled after the Kampar, a river in Indonesia, which the founders designed to add more intrigue — and more colorful animals than the trout of the Colorado River.

But there was a third, unseen path that led to bankruptcy. At first business seemed good, but in 2001 Ocean Journey announced that it would not be able to make payments on $57 million in bond debt and would default on a $6.1 million loan from the City of Denver. In April 2002, it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. By 2003, that bankruptcy reorganization failed, and the complex was sold to Landry’s for $13.6 million.

Landry’s transformed it into the Downtown Aquarium, a restaurant-focused entertainment complex.

Today, Denver’s Downtown Aquarium features eight sections with names like In the Desert, At the Wharf and Rainforests of the World. Vestiges of the original river designs remain, including a flash-flood exhibit that can cause both adults and toddlers to scream when a torrent of water plunges from the mouth of a fake cave in a room illuminated only by flashes of lightning that signal the oncoming flood. The scares don’t end there: A turn around the next corner reveals a fake rattlesnake perched above eye level that unexpectedly hisses, cluing people in to the danger of snakes in the desert.

Landry’s has four locations under the Downtown Aquarium umbrella, including in Houston and Kemah, Texas, and one in Nashville. The Tennessee spot does not have an actual aquarium, just a large fish tank in the restaurant. The Kemah location has a stingray reef and rainforest exhibit that are nowhere near as extensive as the displays in the Houston and Denver aquariums. Denver’s Downtown Aquarium has over 100,000 square feet of floor space and tank capacity of more than a million gallons. As visitors walk through the exhibits, many of the tanks advertise scuba-diving experiences for an additional fee.

Both the Denver and Houston locations are members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums and the Zoological Association of America, nonprofit organizations dedicated to animal welfare that accredit facilities that live up to their standards, which are regularly revised to promote proper animal husbandry. Rob Vernon, a spokesperson for the AZA, says that if a member isn’t following AZA standards, it’s asked to explain why. But the organization doesn’t have legal authority like the USDA, which licenses animal exhibition facilities.

The USDA operates under the federal Animal Welfare Act, passed in 1996, which mandates that it oversee the well-being of mammals. That act specifically excludes fish from its guidelines, however, so the fish on display are not under federal supervision.

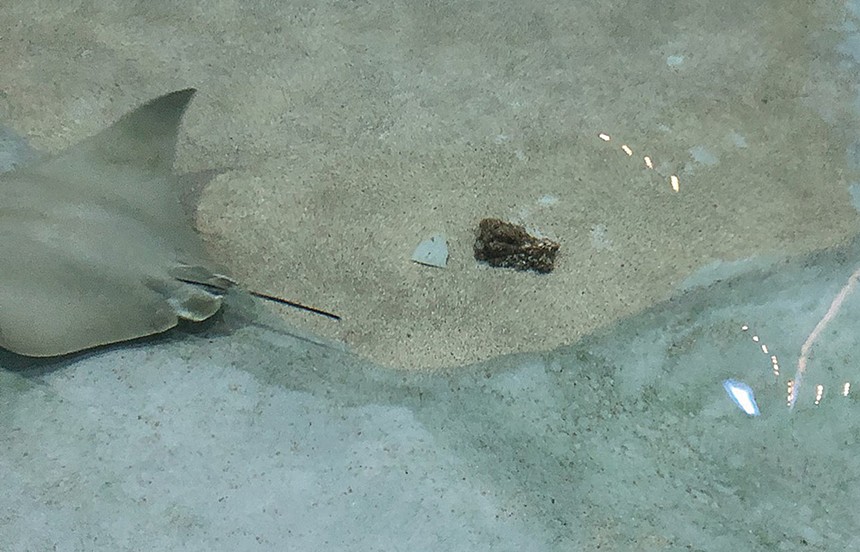

Employees and guests alike have complained about the treatment of stingrays at the aquarium.

Catie Cheshire

Employees say that when they asked aquarium management to fix the damage, they were told the repairs would have to wait until after a September 9 Sip and Stroll event, where guests could drink wine while exploring the exhibits. Management didn’t want the stingray exhibit to be out of commission during the event.

“Clearly their concern is with the guest experience and the dollar, not with the actual treatment of these animals and the quality of their care,” one employee says.

The tank is still not fixed.

Floor employees also report being required to pass out shrimp that visitors can buy to feed the stingrays (an extra $7 on the standard admission) and to allow visitors to touch the stingrays — even when tank water is so low that the rays don’t have the ability to escape. Employees say the aquarists who care for the stingrays are frustrated by the requirement that they be available for touching at all times, but corporate policy holds that stingray petting is never off limits.

Stingray petting is the only interactive experience with animals that comes for free. Guests who want more up-close action must pay $150 for a meet-and-greet with a species of their choice, from armadillos to spiny lobsters.

Staffers are concerned for the well-being of guests as well as the stingrays. They worry that rays could lash out if harassed and injure a visitor. They also fear that when water in the tanks is low, people leaning over to pet the stingrays could fall in.

Although stingrays carry their babies in a pouch like mammals, they don’t fall under the USDA’s purview, and a spokesperson at that agency said that any questions about treatment of fish, including stingrays, should be referred to the AZA, saying the organization keeps stringent watch on such facilities.

Last year a Downtown Aquarium employee submitted a report to the AZA complaining about stingray treatment at the Denver facility, but never received a response.

Although aquariums generally focus on aquatic life, Denver’s Downtown Aquarium houses Sumatran tigers, too. Some of the tigers were acquired when the facility was still Ocean Journey, but a new tiger was added in 2007. When guests switch from the At the Wharf exhibit to the Rainforests of the World exhibit, a sign announces that not even service animals are allowed near the tigers, because any animal could be a tiger’s natural prey or predator.

Any animal except a human, apparently.

Over the years, people have raised concerns about the treatment of the tigers. In 2016, a petition was circulated to free the tigers at Denver’s Downtown Aquarium. That same year, the Animal Legal Defense Fund threatened to sue Landry’s over its Houston aquarium, claiming that its tiger enclosures didn’t meet Endangered Species Act standards. When the ALDF filed that suit in 2017, Landry’s countersued for defamation. The court dismissed the case because Landry’s did not provide enough evidence to show that the ALDF’s threat or lawsuit damaged its business; Landry’s appealed to the Texas Supreme Court. But in October 2021, both parties settled. Meanwhile, the ALDF lawsuit is still pending, according to its website; it plans to re-evaluate the situation after renovations at the Houston facility improved the tiger habitat there.

Questions remain in Denver, however. Star Edwards, a volunteer with the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Keenesburg, wrote a letter regarding the Denver Downtown Aquarium’s treatment of tigers to the AZA and the ZAA. “I’ve been to the aquarium before, and I just thought it was really pitiful to see the tigers in there,” Edwards says. “I understand that it doesn’t do any good to contact the owner of Landry’s but to go after the organizations that so-called certify them. My interest is just, you know, being able to free those animals.”

Edwards says that the Wild Animal Sanctuary, which was founded in 1980 and provides homes for carnivores previously held in captivity, would be a much better place for the tigers. She compares the size of the tiger enclosure at the aquarium to two or three rooms in a normal house — which she insists isn’t enough. When she adopted her dog, someone from the Dumb Friends League came to her home to assess whether there was enough space for the animal in her yard; she thinks that the AZA and ZAA wouldn’t allow tigers to be held at the Denver aquarium if they completed a similar inspection.

“When these kinds of animals are placed in a situation where they’re on concrete, it does stuff to their muscles and their tendons, and they lose muscle tone because there’s no way to exercise their muscles,” Edwards says. “They have good diets, because their fur is sleek, clean, but they look zoned out. Those tigers look bored. They don’t look happy.”“I’ve been to the aquarium before, and I just thought it was really pitiful to see the tigers in there."

tweet this

Indeed, Jalen, one of the tigers, loves naps more than any other activity, according to a handwritten sign. As he makes his way around the enclosure, he walks rather than runs, plodding in a repeating circuit around the enclosure — which might actually be the size of a small house. Still, despite his unhurried pace, his journey only takes about three minutes per lap.

Edwards also worries that the tiger enclosure is air-conditioned and doesn’t give the animals the chance to breathe fresh air or see the sun, even though it does have a greenhouse-style roof. According to aquarium employees, the tigers’ off-exhibit area has sun and fresh air, but one worker describes it as “a kennel.” That employee says the mammal staff asked for improvements to the tiger exhibit, but corporate denied the request.

Houston’s Downtown Aquarium promotes the tigers on its website; Denver’s barely mentions them. Houston’s website says this about sanctuaries that house tigers: “While people are often drawn to the word sanctuary as it sounds like a peaceful place where animals can retire, many sanctuaries are underfunded and understaffed with volunteers who are not qualified to work with large carnivores...The Houston Downtown Aquarium is accredited by AZA and ZAA institutions. Many sanctuaries ARE NOT accredited facilities because they cannot meet the high-quality standards set by these organizations.”

Edwards argues that the AZA and ZAA shouldn’t allow their accreditation process to be used to defend poor treatment of animals in captivity. “I think that it’s really important to put pressure on the organizations that are so-called giving people certifications when they don’t deserve it,” Edwards says.

She also calls out Fertitta, who owns the NBA’s Houston Rockets, for acting like he is saving tigers by housing them in his aquarium.

“The Aquarium attempts to ‘teach’ the public about saving wildlife in a most unnatural environment possible,” Edwards wrote in her letter to the AZA and ZAA. “They believe they are contributing to saving a species of tigers from extinction in our lifetime, yet they are no more than a glorified road side zoo. … What it does teach guests is that very rich people can use these animals on display to make money for profit.”

Edwards says she received no response from the AZA or ZAA. She also sent that letter to several other wildlife organizations and her state representative, Leslie Herod; she only heard back from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, whose response she found unsatisfactory.

The ZAA did not respond to requests for an interview from Westword. According to the AZA’s Vernon, Landry’s plans to upgrade its Denver tiger enclosure, adding more enrichment, as it did in Houston. Although Vernon says that the AZA’s accreditation commission reviews every concern sent its way, he did not respond to a question about complaints regarding Denver’s Downtown Aquarium.

The USDA oversees permits and inspections for animal exhibition facilities, including aquariums. According to inspection records, the USDA has found no issues at either Landry’s facility. But the only creatures included in its Denver inspection were tigers, otters and four other mammal species.

The Downtown Aquarium is exempt from Colorado Parks and Wildlife licensing requirements, because the state considers it a zoo. Travis Duncan, a CPW public information supervisor, says CPW has long exempted from regulation any facility accredited by the AZA; the department has digitized its records back through 1998 and the exemption originated before then, he adds.

In 2014, CPW updated that rule to specifically exempt the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Denver Zoo, the Downtown Aquarium and the Pueblo Zoo from the requirements of Parks and Wildlife Commission regulations. It isn't clear why those facilities are exempt, he notes: "Unfortunately, the regulatory archive doesn't provide that much more detail on the reasoning."

Denver Animal Protection will respond to specific complaints about animal wellness at facilities in the city, even though the primary regulator is the USDA. The department performed one wellness check related to the tigers on November 1, the same day a complaint came in, but didn’t find signs of mistreatment, according to Emily Williams, director of communications and marketing for the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment.

Two-legged animals at Denver’s Downtown Aquarium may not be treated that well, either. When Denver re-established a mask mandate on November 23, management sent an email to aquarium employees telling them not to worry about enforcing the policy; employees say that when they ask guests to put on masks, management does not support them.

They also say that throughout the pandemic, they’ve been required to come to work even if they are awaiting COVID test results. The only acceptable excuse for missing work is a doctor’s note; if an employee doesn’t have a note and is out sick, the employee receives a warning. Three warnings result in termination. Workers say that there have been several times when employees were told to come in despite COVID symptoms and pending test results, and learned they were positive while at work or after a full shift of interacting with guests.

Only four signs in the facility announce Denver’s mask mandate, including one that was added in the stingray reef only after employees repeatedly asked management to increase signage. Employees think it was designed to be unclear; rather than using materials provided by the city, the aquarium made its own wordy sign.

Employees say they’ve reported the aquarium to OSHA’s whistleblower program for unsafe COVID practices several times.

COVID may not be the only health threat for humans. Employees who work at the Starbucks kiosk on the aquarium floor, which is operated by Landry’s but sells Starbucks products through a partnership with Nestlé, say that those products are often expired. Last fall, two employees took all the expired items from the storage closet, separating them into bins. Espresso, teas, juice concentrates, syrups and toppings were among the items whose expiration date had passed; some had expired just a few months before, but others had expired as early as 2018.

“I reported this fact to my management team and asked how to proceed,” one employee notes, “and was told to simply ignore it and keep selling the product, as ‘We can’t get rid of that much at once.’” Management said she could either sell the products or be scheduled in different departments until they were sold, she recalls; she chose to work in other departments, many of which she wasn’t trained for.

Another kiosk worker says she lied to customers, telling them that the aquarium didn’t have pumpkin spice syrup because it was company practice to use syrup left from previous years even if it had expired. Management punished her, she says, and insisted that she sell pumpkin spice if people asked for it. Through a spokesperson, Nestlé says, “We understand the aquarium has investigated this and found no instance of the cafe using expired product.”

And then there are the cockroaches. They’re not uncommon at aquariums, because they’re drawn by moisture, heat, and food and water sources. But since Denver’s Downtown Aquarium is also a restaurant, cockroaches can be a problem.“We understand the aquarium has investigated this and found no instance of the cafe using expired product.”

tweet this

According to several employees, there are cockroaches in the room where the Starbucks products are stored. One says flipping a switch in that room can sometimes be like a scene in a horror movie where the bugs skitter away upon seeing the light.

The Denver Department of Public Health and Environment says it has not received complaints related to cockroaches at the facility. But in September 2021, the Downtown Aquarium was cited by Denver Public Health for poor hygienic practices, food temperature control and plumbing issues. A re-inspection found the problems fixed, though plumbing issues keep reappearing.

Other non-physical factors contribute to what employees describe as a toxic work environment. Several workers say that scheduling is done so poorly that it’s hard to rely on a consistent paycheck. One says that management forgot to schedule her for an entire pay period.

When employees do get scheduled, they say they are often asked to close one day and open the next, or are assigned to positions for which they weren’t trained. One says she was promised full-time work but is routinely only scheduled for about 25 hours a week. Employees who work at the Starbucks kiosk say they’re sometimes sent home if the aquarium is slow, losing hours they’d counted on.

When they do work, employees aren’t given lunch or even breaks during their shifts, according to five employees Westword spoke with. Even if they need to use the restroom, they are not given permission. “In the time I worked there, I never had a break,” says one former employee. Colorado labor law states that employers must give a ten-minute break for every four hours of work and two ten-minute breaks for over six hours of work.

One employee tried to report the aquarium to the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment for manipulating and denying breaks but couldn’t find a way to do so anonymously; complaints must be made through an account registered with an employee’s name and workplace. “That’s kind of a big deterrent for me,” says the worker, who doesn’t want to be known as a troublemaker.

Despite the problems at their workplace, and although there are many other job openings around the city, some employees want to keep their positions at Denver’s Downtown Aquarium because they want to stay in the aquarium field.

Aside from SeaQuest, an aquarium in a Littleton shopping mall whose license was suspended in 2019 after a string of animals died there, the Downtown Aquarium is the only place in metro Denver where people interested in a career in aquarium management can work.

A few employees who particularly value marine education say they approached management about creating educational content for the company Instagram, which mainly posts event and restaurant promotions, along with a post or two about what a great place the Downtown Aquarium is to work. But management told them that the education departments at all Landry’s aquariums lost Instagram privileges after one posted a message about the importance of consuming sustainable seafood, which the company described as a “conflict of interest.”

“I feel like I can’t, and so many other people there can’t, do the quality of a job that they would like to be doing and get the value out of their job because of the way that management handles things and the way that Landry’s handles things,” one employee says.

According to several employees, when they joined the floor staff at the Downtown Aquarium, they were told that the aquarium often promotes from within and that they would have the chance to climb higher in the education department or to other marine-life positions. All of them have worked at the aquarium for over nine months, but none have moved up.

“I keep holding on to the hope that I’ll be able to move further up,” one says. “I want to do stuff in the marine and aquatic field. I feel like if I stick it through, maybe I can get enough experience to move somewhere else.”

For now, the employees keep their jobs and try to do what they can to make the Downtown Aquarium a worthwhile experience for guests.

But as long as the facility continues to be popular, they worry that everyone from Fertitta on down won’t be motivated to think about education, animal care or employee treatment.

“They’ve gotten so attached to the money that comes with their jobs and whatever else that they don’t care about their employees,” one worker says. “They don’t care about anything else. I want something to change. People need to pay attention. Please pay attention to this."

This story was updated on January 27 to include more detail on facilities such as the Downtown Aquarium that are exempt from Colorado Parks and Wildlife oversight.