Tim Miller is the sort of guy who’s as at home on Fox & Friends as he is on MSNBC. You may have seen him on both recently, speaking for the “Never Trumpers,” people who left the Republican Party either officially or unofficially when it became clear that Donald Trump had effectively become the entirety of the GOP platform.

Miller, who was born in Littleton, became a Republican Party activist early. At sixteen, he served as a political intern to an Iowa staffer campaigning for John McCain in 2008; in 2012, he was national press secretary for the Jon Huntsman campaign. By 2016, he was communications director for Jeb Bush — which is also when he became an outspoken opponent of Trump. When that Bush dropped out of the presidential race, Miller went on to participate in several organizations devoted to expunging the Trump effect from the GOP. But disillusioned with the process he’d hoped to change from within, he left the Republican Party in 2020.

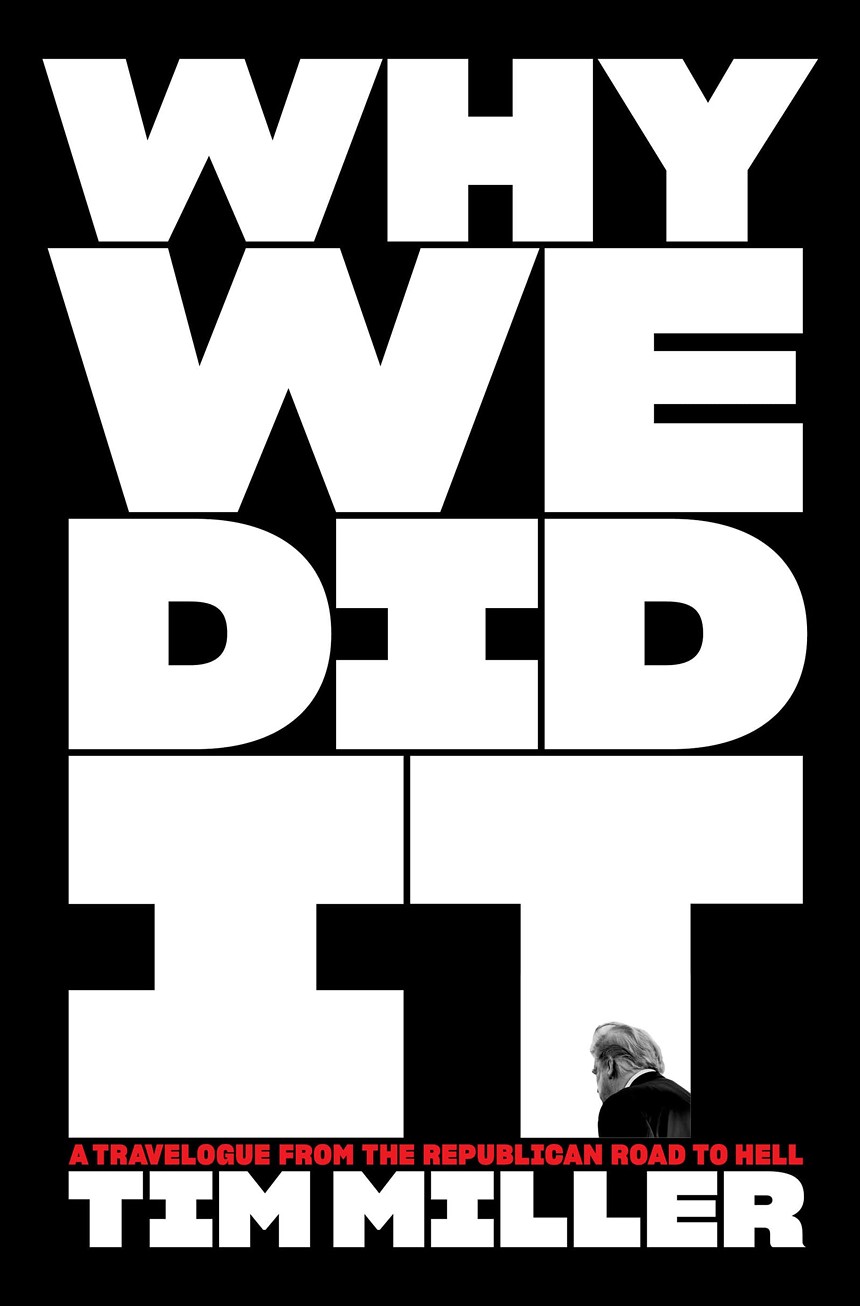

Miller has detailed this journey through Republican politics — not only his own, but those of several colleagues – in a new book, Why We Did It: A Travelogue From the Republican Road to Hell. There’s not much gray area in that title, and that’s sort of Miller’s point: to face up to where we are as a nation, determine how we got here, and maybe figure out how we can return to something resembling political normalcy. In advance of his Tattered Cover appearance on July 21, we reached out to Miller to talk some of this out.

Westword: So why this book? And why now? This seems like a process you’re moving through, so why was now the right time?

Tim Miller: Look, I was a Never Trump Republican. I bailed on the party in 2016 and supported Hillary. But throughout the past seven years, I’ve still struggled with the central question of this book, which is: Why did all the people I’d worked with, all my old friends, go along with something that was so evil? Something they told me they knew was evil? And why did they continue, even after the January 6 insurrection? So I had to do two things: One was to reflect back on how I went along with things that in retrospect I knew were against my values, and the other was to go interview my friends who were willing and try to get an honest answer from them. As honest as anybody is willing to be with themselves.

So take us back to where you started in politics — that was here in Colorado, right? Bill Owens's successful run for governor in 1998?

I was a kid; I looked like I was eleven. Everyone asked me where my parents were. People were asking me when I got in the car to go to a campaign event if I needed a phone book to sit on. I was there from early on out of circumstance, really. My neighbor knew him. I was still in high school, so I interned on the weekends. When he won against Gail Schoettler by a hair, it was exhilarating. I got really wrapped up in the excitement of it: the winning and the losing, the competition. Owens was losing the whole night and then came charging back, and I’m sixteen and it’s like 2:30 in the morning on a school night. Everybody’s drinking except me, everybody’s partying, we’re up on stage together. While there are still elements of conservative philosophy that drew me to the party, eventually it got taken over by that rush of the politics of politics.

So looking back, how did Bill Owens stack up against the far-right GOP that was coming?

Owens was maybe a little more conservative than me. He was a middle-of-the-road Republican, and I was always a moderate Republican [laughs]. One of the things I write about in the book is how I compartmentalize things that are inconvenient. I really don’t even remember what his position was on gay issues. [Miller has been openly gay since coming out in 2007, partially in response to the Larry Craig scandal.] I mean, he was a Republican in 1998, so he had to be against it, but I don’t remember it being a hot button of the campaign.

I grew up right by Columbine, and Owens was pretty pro-gun hardline. At the time, I was persuaded by that. I’ve moderated, but at the time I thought Columbine was a black swan, that maybe — and this seems so stupid now — but maybe if the gym teacher had a gun, that might have dissuaded these kids from doing it. So Owens and I were sort of in-line then; we’ve parted ways on that and I’m sure a number of other issues over time.

And that experience set you up for your first presidential campaign in 2008, working for John McCain?

Yeah. I actually thought John McCain was more moderate than me. On campaign finance, for one. McCain was the one who persuaded me that what the Bush administration was doing in Guantanamo and elsewhere was wrong. The first thing he said he was going to do as president was cap and trade for climate change. You’re always going to disagree with your candidates on some issues. I disagreed with some candidates before Palin on different things, but it was always within the bounds of normal politics. But then there’s the anti-immigration hardliners rising, the anti-Obama race-baiting stuff rising, and the extremism of the Tea Party across issues. Even on stuff I agree with, like fiscal responsibility, but shutting down the government? The cruelty and extremism were there in 1998. Owens had a primary from the right. But they weren’t in charge. Now they’re supercharged.

You refer to yourself as a RINO (Republican in name only) several times in the book. Is that an effort to reclaim that as a non-pejorative? Is it just shorthand? What does it really mean to you?

It’s kind of like the gays have reclaimed “queer,” right? I do it tongue-in-cheek, really. I’m technically not a RINO anymore, since I left the party officially during the Stop the Steal stuff. But the candidates who were smeared with that name during the primaries were the candidates I liked. The ones who recognized that climate change was real. They might not have agreed with the Democrats’ prescriptions, but they agreed something had to be done. The ones who supported gay rights, were more welcoming of immigrants. There was a faction of Republicans who held this view — a diminishing faction over time. But I wanted people to know where I’m coming from.

A lot of the book is about how you — and a lot of your colleagues — were “channeling the dark arts of politics to positive ends.” Isn’t that still what’s happening, for the most part?

Yeah, but it’s not true. That’s the realization that I come to in the book that some of my friends haven’t come to yet. You know, can I help get my more moderate candidate through by participating in subterfuge, smearing the enemies, whatever? And yeah, maybe that was a net positive in some cases. So you tell yourself, okay, here are these examples where I helped somebody who matched my values, and that’s something I can feel good about, help me rationalize all these other times when I’m smearing Democrats with things that I know are hyperbole, or aren’t even true. Or other times when my candidate was going to have to pretend to like this immoral thing because that’s what he needs to get in there. I look back on it with regret, but I think in some ways it was a rational position to hold. Everyone had their dividing line. Maybe not until ’08, when Palin got picked, or ’10 with the Tea Party. But certainly, you have to stop believing this is positive in 2016 when a madman takes over the party and the presidency. Then, obviously, you’re not nudging things in the right direction, and yet still, throughout the Trump years, my friends in the political class kept saying, “Well, it’s better that we’re in here. Maybe a white nationalist might take my job if I’m not here.”

These are the folks you refer to in the book as “Little Messiahs.” It’s a complex position; how do you respond to that argument?

By treating Trump like a toddler, people who convinced themselves that they were helping and serving the country actually extended the potential damage. It’s a crude thing to say, but had Trump been allowed to do some of the more dangerous things that he wanted to do, maybe we could have had seventeen Republicans with balls who voted to convict him, and then we would have been done with this.

No exceptions?

H. R. McMaster decided to be the national security advisor because he wanted to make sure that this insane person who just got elected didn’t push the nuke button. He gets a pass on this; I think that was well-intentioned. But if you’re, say, the communications director whose job it is to make Trump’s crazy thing sound a little less crazy so it’s more palatable to voters, are you helping the country? Or are you just enabling Trump to maintain power longer? I think a lot of these people were telling themselves they were helping the country, when all they were really doing was helping their career.

Part of your own response to the Trumpian threat was to start Our Principles PAC, an anti-Trump Republican organization that went by the acronym OPP. I’m not sure how that’s not a Naughty by Nature reference.

Oh, it was. We had T-shirts made.

And when OPP folded, almost everyone who worked there went to work for another PAC, this one called Future 45. Which was pro-Trump. Isn’t that exactly the problem in a nutshell?

Yes. There’s something in the water in Colorado, because the only two people who didn’t go from anti-Trump to pro-Trump were me and Katie Packer Beeson, who lives in Colorado. So the two Colorado connections to OPP were like, “This is too disgusting for us.”

But yeah, it’s the most stark example of what we saw over and over again, which was people removing the question of integrity from their job. The message of this book is not that politics shouldn’t be a competition. It’s not that you shouldn’t try to win. The message of this book is that in any job, you have to ask yourself, "Is what I’m doing within my integrity? Am I being a net good for society by being here? What are my red lines?" It turns out that the Republicans have become so nihilistic and so corrupted that no one even stopped to think about these questions. We in politics have a responsibility to public service, and that’s been completely lost. I’m hoping I can inject some of that back into my old friends’ mindsets. That we step back and reconsider what is outside of our integrity

So what comes next? At one point in the book, you mention “Democrats' bed-wetting nature” as a reason they’re not doing better. If you were going to advise the Democratic Party’s national run, what would you do differently? I’m not talking policy, I’m talking candidates and strategy.

The extremism on the right is really another level. Across the country, most of the Republican nominees —and Lauren Boebert is a prime example of this — are more conspiratorial and more extreme than even anything coming out of the Tea Party. Democrats are in some way letting themselves become defined by their most liberal members, and Republicans in a lot of cases are not. Part of that is the Democratic strategy. They need to be a little more aggressive at targeting those extremists, while at the same time acknowledging that they might have to sacrifice some things that they think would be in a perfect world. I attack the Republicans in the book for being so nihilistic that they’ll use any tactic necessary to win. Sometimes the Democrats fall too far on the other side of that continuum, where they care so much about the purity, the right thing to say and the social good. It’s an admirable quality, and it can sacrifice a candidate’s strength. They need to find a balance.

Tim Miller will discuss Why We Did It: A Travelogue From the Republican Road to Hell with Kyle Clark of 9News at 7 p.m. Thursday, July 21 at the Tattered Cover, 2536 East Colfax Avenue. The event is free; for more information, see the Tattered Cover website.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]