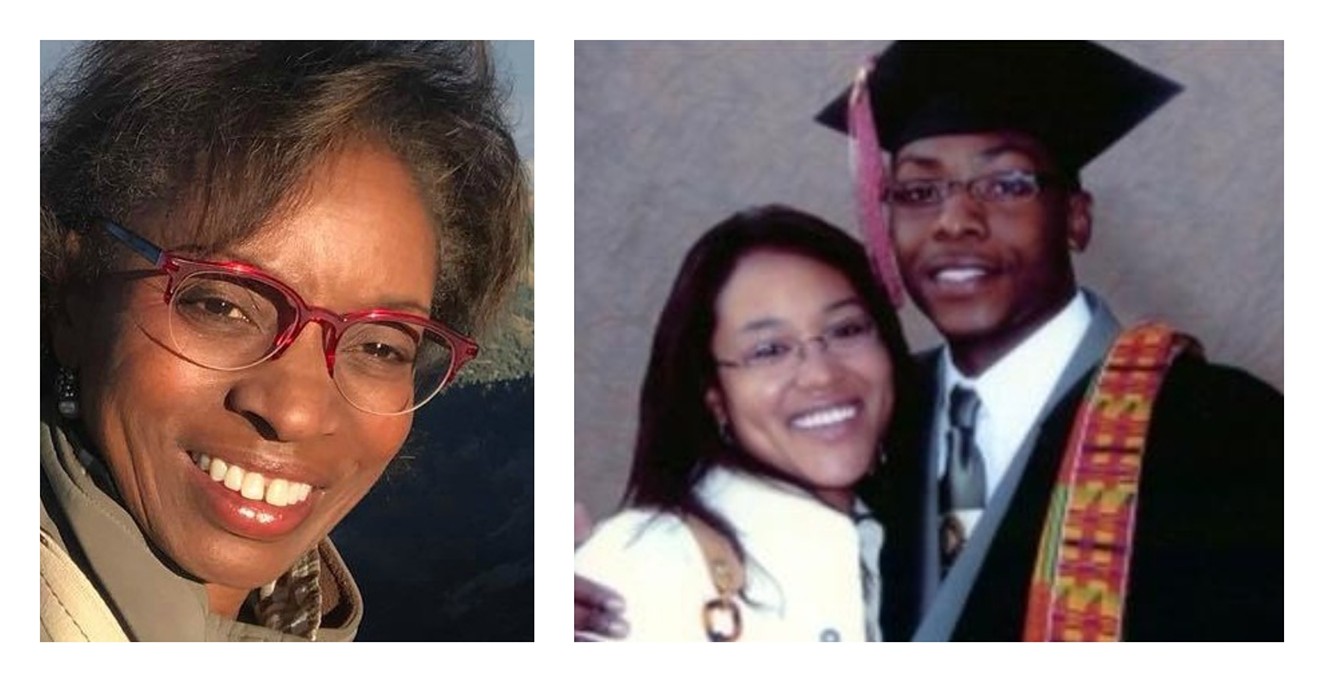

State senator Rhonda Fields has devoted much of her energy while in office to shoring up the rights of crime victims — a need she knows from horrific personal experience. In 2005, her son, Javad Marshall-Fields, and his fiancée, Vivian Wolfe, were slain before they could testify as witnesses for the prosecution in a 2004 murder case.

Nonetheless, neither Fields nor her daughter, Maisha Fields, received any notification that Percy Carter, who was convicted as an accessory to the crime, had been released from prison until he'd already been freed and moved back to Aurora, just over a mile from Fields's longtime residence.

"I'm his senator," Fields told Westword moments after she appeared in Arapahoe County Court yesterday, September 13, when she was granted a restraining order against Carter. "I found out he lives in my district, in a place where I'm around all the time. I'm quite sure he's seen me and knows where I live. I still live in the same house Javad was raised in."

The judicial process clearly didn't work as intended, Fields stress: "I got part of the notification, but by the time I did, he was already out and about."

Adds Maisha Fields: "If this is happening to Senator Fields, it's happening to other victims of violent crime, whether it's domestic violence, homicides, home invasions. Victims are not being notified, and the criminal justice system isn't adequately protecting victims."

The individuals convicted of killing Marshall-Fields and Wolfe, Sir Mario Owens and Robert Ray, won't be returning to the neighborhood. Both were originally set to be executed for the crime before then-Governor John Hickenlooper converted the sentences of all inmates on Colorado's death row to life without the possibility of parole in 2013. Seven years later, the state's death penalty was repealed.

Owens and Ray weren't the only ones involved in the crime, however. Parish Carter, Percy's son, was arrested for intimidating Marshall-Fields and Wolfe the night before they were killed, and he was eventually convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and more. In addition, Percy was found guilty of acting as an accessory for harboring his son during a period when he had been named in an arrest warrant and helping to destroy evidence — specifically trying to disassemble and get rid of the guns used in the fatal attack.

In the meantime, Fields fought back legislatively. "I've run so many public-safety bills," she says. "I ran bills to fund the victims notification system, called VINE. I ran legislation to improve the Crime Victims Rights Act. I'm very familiar with victims notification — but something fell apart when it came to this offender. I wasn't really advised until he was already released, with no more supervision from the Department of Corrections or adult parole. When I got my email notice, he was already in the community I represent, and that didn't feel right."

The hearing "was very traumatizing," she says. "I had to explain to the court why I was requesting a protective order, and the line of questioning made me ask, 'Why do I have to explain this? Two people are dead.' Yes, he served his time and he's now no longer in custody, but I think that's more of a risk, because he doesn't have to check in with anybody." The judge in the case "kept saying, 'Have there been any recent threats? Why do you think this?' And I said, 'Because of who I am and what happened to his life.'"

In the end, the order was granted, but "the whole process was not very pleasant," Fields says. "It was in the same courtroom where I saw a jury come back with guilty verdicts not once, not twice, but three times. I also had to pay for the order — it cost me $53 — and I had to take it from the court building to the sheriff's department, which serves the papers. And the sheriff's department is next to the county coroner, where I identified Javad's body."

The experience could fuel yet more legislation. "I will be conducting an audit to find out the process map of how things should work, to make sure there are no gaps," Fields notes. "No one should be startled by getting confronted by their offender at the gas station, and that could have happened to me. We have laws to prevent that from happening. Every victim is supposed to be notified of any activity regarding an offender's movements — when they're transferred from facilities, when they're up for parole. And I did get those notifications, but I don't recall any parole notification or statement, and that should have been part of the protocol. So I'm going to explore what that's all about."

Revisiting these events won't be easy, Fields admits, "but it's also healing. The healing part is in the resolution and trying to do right by those who've been victimized and harmed by crime. That's where I get my sense of well-being."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]