When people who knew Clayton Counts saw a Facebook memorial account for him, they assumed it was a joke. That would be his style. He had faked his own death on at least one occasion and left in his wake a long string of pranks. Sadly, this was no hijinks.

In November, the musician overdosed on opiates. Few in Denver could make it to Texas for his funeral, but they still wanted to honor his creative legacy and friendship. To that end, on Sunday, February 12, Mutiny Information Cafe will host a memorial show, where Counts's friends and bandmates will perform.

Born with detached retinas, Counts had been in and out of hospitals for surgeries to treat his condition and related health issues for most of his life. Originally from Marble Falls, Texas, he gained notoriety in Austin for prank-calling Alex Jones's community-access radio show. The right-wing radio host temporarily persuaded the FBI to categorize Counts as a terrorist and accused him of possessing child pornography. Neither was true, and the cases against Counts were dropped.

Around 2000, Counts relocated to Chicago. He was a regular at the Atomix Cafe, where he met his future roommates and bandmates Neil Keener and Chuck French, who worked there. Both assumed he was just another weirdo who came to the coffee shop every day to rant about his obsessions.

“We had to throw him out at least once a week for screaming at people,” says Keener.

“He was a maniac,” says French. “There were a lot of oddities around that coffee shop.”

Every month the shop had a Customer of the Month, meaning the customer in question enjoyed free coffee. “He wanted it real bad, which is why he never got it,” says Keener. “But the owner decided that we would have one day a month that was '[International] Claytonia [Day],' and we made him a cake and banners.”

“We made him a sash that said, 'Don't mess with Texas,' and he had American flags in his beard,” says French.

“I couldn't stand him at first,” says Keener. “But there was something about him that was interesting, and he was a really good person.”

Counts possessed a great body of knowledge about linguistics, literature, music, film and computer technology. Because of the condition of his eyes — he was legally blind — Counts was on disability. Nonetheless, he became a popular DJ in Chicago before he relocated to Denver around 2007, following a September 2006 cease-and-desist order from the record label EMI for his mash-up of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, under the moniker the Beachles.

Counts wanted to get out of town, so he contacted his friends Keener and French, who had moved to the Mile High City to pursue their lives in music. Both maintained their Chicago band Git Some, in which Counts was briefly the vocalist, and both ultimately became members of Planes Mistaken for Stars.

French and Keener lived in downtown Denver at a place called the Tree House, at Fourteenth Street and Tremont, and for a few years they all lived in warehouse conditions, without heat. After Counts moved in, he occasionally dragged a piano out of the house to play on the 16th Street Mall.

Counts was a prolific musician, and in 2008, he and Keener formed Bull of Heaven, an experimental band whose catalogue now includes upwards of 500 releases spanning eight years. The group recorded an album that has a track time exceeding eight septillion years — which is many times longer than the age of the known universe.

“Clayton became obsessed with making the longest piece of music that he possibly could,” says Keener. “He found a way to make loops the lengths of prime numbers so the loops wouldn't repeat again for longer than you can calculate. So we made a few pieces like that. You can find it all on the archive.org website section for Bull of Heaven.”

The project had started as four-track recordings of experimental guitar drones and other sound ideas Keener had concocted, but Counts's computer wizardry helped to transform the music to another conceptual level. Although Bull of Heaven didn't often play live, its spirit of pure experimentation and pushing ideas to their logical conclusion made an impact on anyone willing to take it on its own terms.

“He was a genius producer,” says Keener. “He understood sound in a way I don't. I would give him a shitty stereo mic digital recording of a jam I had with some dudes that hung out at Yellow Feather Coffee, and he would turn them into album-quality-sounding pieces. I have no fucking idea how he did that.”

Counts made friends beyond his immediate circle because he could and often would talk at length about various subjects with anyone who would listen.

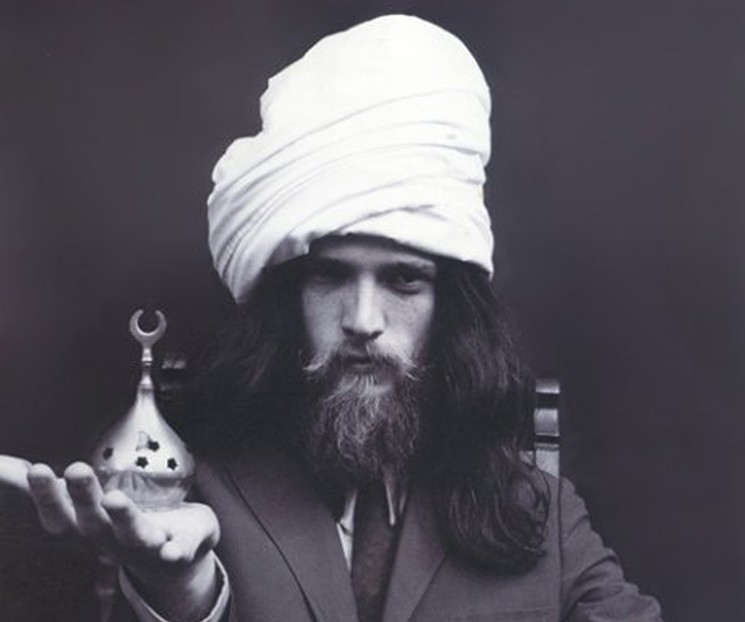

“I didn't even know he had a Wikipedia page until he died,” says friend Steven Lawson. “He was one of the smartest people I ever met and definitely one of the craziest, too. Clayton kind of lived in another dimension. He had almost no social radar. He would blather on about a super-massive black hole or something, and you would have to just walk away from him with his crazy eye and his beard like Rasputin.”

Says Lawson: “With him gone, the world is a little less strange and interesting and magical."

Clayton Counts Memorial, with Git Some, Steven Lee Lawson, John Wenner and Bull of Heaven, at Larimer Lounge, on Sunday, February 12. Doors 7 p.m.. For more information, call 303-778-7579.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]