Strong Island premieres on Netflix on Sept. 15

The tragic truth remains that all it takes in America for a white person to get away with killing a black person is for the white person to convince the right people — a judge, a jury, a prosecutor — of his or her own fear. If a white person is scared enough of a black person to believe that his or her life is in danger, our legal system insists that the white person is justified in killing. As a white person who grew up among white people, I must inveigh against the madness of this standard: It’s an abomination to allow white people’s fear of their idea of black people to exculpate the murder of actual black people.

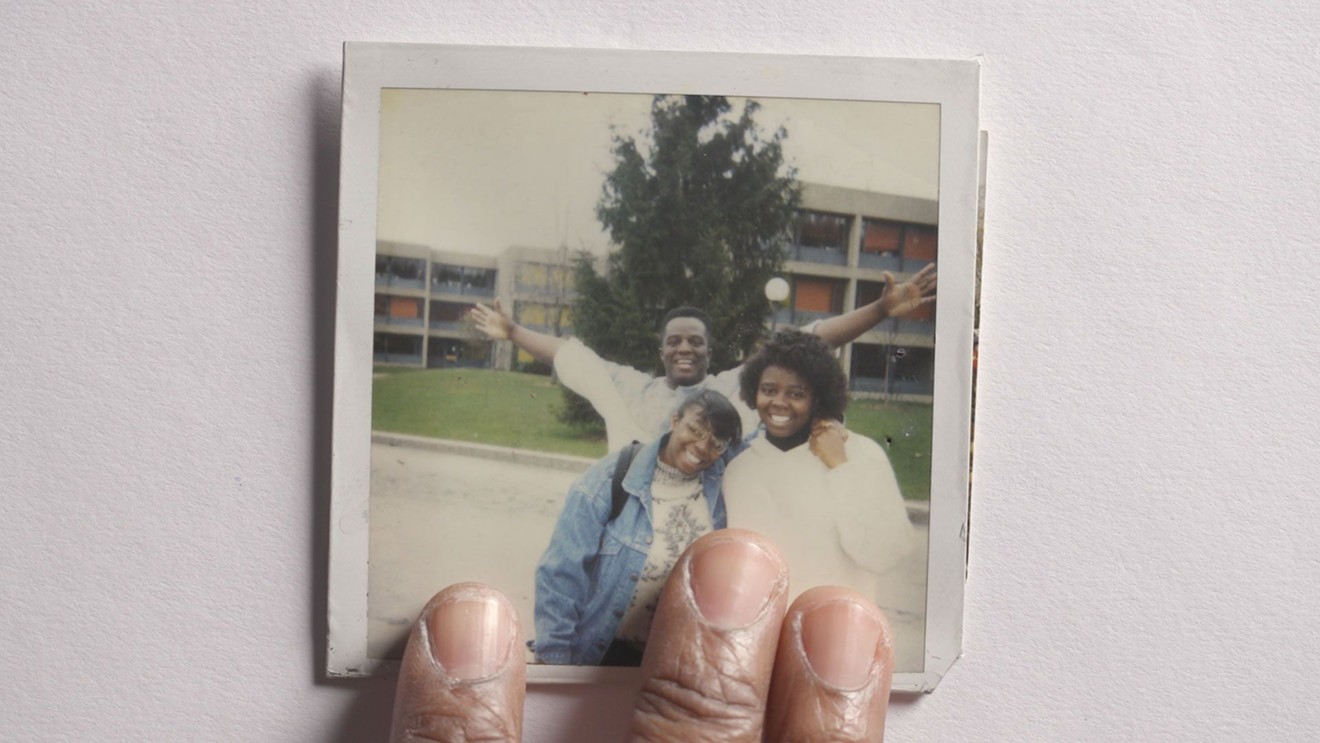

Yance Ford’s courageous, intimate, heart-rending Strong Island examines, with wrenching clarity, one such case. Ford’s brother William was shot and killed at age 24 in a Central Islip automotive chop shop in the spring of 1992 by a white man who convinced the cops and the grand jury that he had every reason to fear for his life. Yance Ford tells us, in the film’s opening moments, that Strong Island is her chance to set the record straight not just on William’s death but on his very character — as in so many cases of black men killed by white men, the white man’s exoneration depended upon the black man’s demonization. Director Yance, who is transgender, reveals William to us through interviews with family and friends, through excerpts from William’s own diaries (he was on a fast to make the weight requirement for a job as a corrections officer), through the testimony of a Manhattan assistant district attorney who, the year before William was killed, got shot on the street and watched William heroically chase down and tackle the shooter. Days before William’s death, the young man testified in court about that other shooting; after William’s death, the Ford family was kept in the dark about the case against his own shooter. Yance reads to us from a letter that their mother, Barbara Dunmore Ford, sent in May 1992 to the district attorney investigating the death of William: “My son was not armed, not violent, not aggressing. In no way is his death justifiable.” Later, in one of the film’s many piercing interviews, William and Yance’s mother, says, “I did William a great disservice in raising him the way we did. We’ve always tried to teach you guys that you see character, and not color. And many many times I wonder how I could be so wrong?”

The story turns out to be more complicated than she knows. Yance breaks down, on camera, late in the film, and confesses to having hidden from their mother one piece of information: that, before the night in question, William had been involved in an earlier altercation at that chop shop, where the mechanics had pledged to fix the family car but kept not getting around to it. From no moral standpoint does that justify his eventual shooting, of course, but the all-white Long Island grand jury in 1992 accepted it as legal justification. Those 23 people ruled there was insufficient evidence to prosecute the shooter. Yance, in the film, acknowledges the facts of the case while also giving full vent to despairing outrage. For all its raw pain, Strong Island is also a scrupulously shaped work, one of striking compositions and juxtapositions, its faces and revelations presented with artful, thoughtful rigor. Especially compelling is an early thumbnail history of African-American neighborhoods on Long Island — and of the lesson, learned early by the Ford kids, that when you stepped out of your haven and into a white area, you better run.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]