Officials tell Patrice that her son is in “limbo.” He still hasn’t been able to pass the test to be declared competent, but he is not “state hospital material," they say, meaning he's not enough of a potential danger to himself or others to mandate permanent confinement and 24-hour watch. This gray area has meant that Kyle has been detained for over a year, before ever standing trial for his crimes.

Coloradans like Kyle who are declared incompetent to proceed in court have long faced a catch-22 in the criminal justice system that leaves them languishing in jails or state hospitals for months, sometimes even years, before they have ever been convicted of a crime. In August, however, Kyle may be the first to benefit from a change in the Colorado statute that could get him out of jail and into a community-based treatment program.

The new laws, Senate bills 222 and 223, are intended to streamline the process of determining competency and hold the state accountable for moving people through the system without massive backlogs. They also demand that the state figure out how to address some of the much deeper problems that have swept these people up in the criminal justice system in the first place.

Patrice sees a fear-based reasoning underlying the system that has kept her son behind bars. “Any time there’s a mental health issue, people are like, ‘Don’t let them out, what are they gonna do?’...so they err on the side of keeping people confined,” she explains. But, she says, that system has failed to make an exception for people like Kyle, who has never committed a violent crime or shown any inclination toward violence.

As Allison Butler, an attorney with Disability Law Colorado who has long worked on these issues, puts it, those who are declared incompetent too often become “lost in the system” and “end up spending time in jail or a state hospital when they shouldn't be.”

The concept of competency rose out of a series of 1960 Supreme Court Cases, which determined that it is a violation of due process to try to convict a defendant who cannot understand the court proceedings or to assist properly in his own defense. (The question of whether the defendant understood what they were doing when they committed the crime is a different issue.)

The statute is meant to protect people with cognitive disabilities, severe mental illnesses or substance use disorders, as well as people with traumatic brain injuries. But in practice, in Colorado and elsewhere, it’s become a case in point for both the inefficiency and the human cost of using the criminal justice system to deal with some of the most marginalized people in society.

“I believe in the concept of due process that’s animating the idea that people should not be required to stand trial if they are that mentally ill,” explains Kristen Nelson, a former public defender who was one of Aurora theater shooter James Holmes's lawyers. Nelson now directs the Powell Project, which focuses on assisting defense counsel in death penalty cases. Last year, she also worked with a public defenders’ office to research why so many people were lingering in hospitals.

“The criminal justice system has become the de facto place to take care of people with mental illnesses. As a society we don’t understand mental illness very well; the way people behave can be frightening,” Nelson says. “We put them in jail because there’s nowhere else for them to go.”

The process of competency evaluation in Colorado is theoretically simple: If any party involved in a case — the police, the judge, the prosecutor, but most often a public defender — suspects that the defendant doesn’t have the mental capability to understand the basics of his or her legal situation, that person can refer the defendant for competency evaluation.

If deemed incompetent, the defendant must then go through a process called “competency restoration,” which teaches people very basic information about the justice system (for example, “What is a judge?,” “What is a prosecutor?,” according to Butler). The aim is much more modest than “restoring” the person to mental health or treating their illness, though they may also receive treatment like psychiatric medication or cognitive behavioral therapy. At its core, though, restoration simply means that the person can pass a test that declares them competent enough to understand what is going on in a courtroom. Then they can proceed with their case.

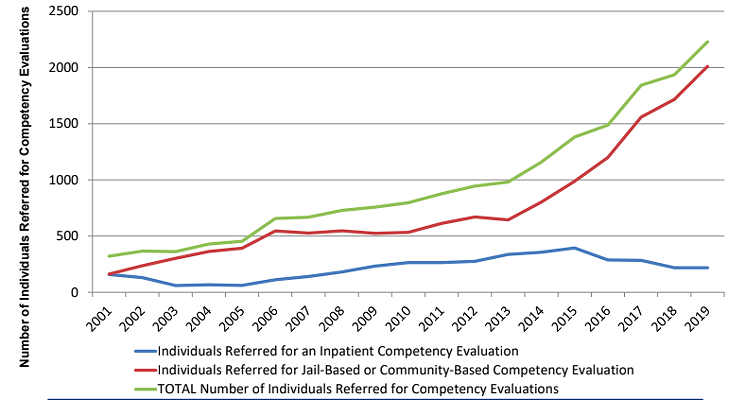

Since 2000, Colorado has seen a 592% increase in court-ordered for competency evaluations, and a 1,251% increase in those referred for services

Colorado Department of Human Services

The root cause is a 592 percent increase in court orders for competency evaluations since 2000, and a 1,251 percent increase in those referred for services. According to Robert Werthwein, director of the Office of Behavioral Health at the Colorado Department of Human Services, the reason for that spike is not entirely clear, but it’s a nationwide trend. One reason, Butler says, is that “we have de-institutionalized [people with mental illnesses] without giving them other support.”

According to a 2015 federal court order, no one is supposed to wait more than 28 days to be evaluated for competency, and no more than 28 days after that to get restoration treatment. But the demand was so high that the state hardly ever met those criteria. Adding to the strain of increased demand were bureaucratic regulations that didn’t help: People would have to be shuttled to the state hospital in Pueblo to get evaluated, then shuttled back to wait in jail again, before finally being admitted for restoration.

Moreover, whereas restoration is supposed to take no longer than 120 days, some patients end up waiting for much longer. Others never pass the test. They are declared “permanently incompetent” and usually placed in a mental institution. It’s clear to Nelson, who has met with dozens of people in that situation, that some need hospital-like 24-hour assisted living care. But, she says, “the hospital at this point is only supposed to be for Pueblo criminal charges. ... There is a fairly large group of people down there whose cases have been dismissed but they are still there.”

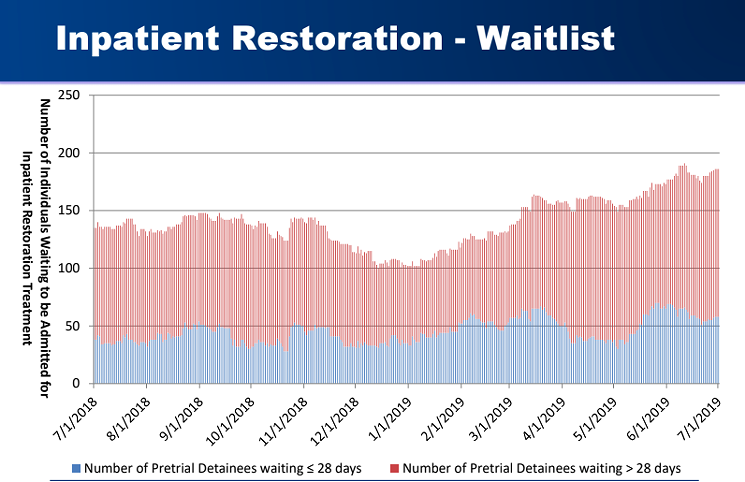

As of last March, the average wait time in jail before getting admitted for competency restoration was still 79 days. And as of the beginning of July, there was still a waitlist of over 150 people, most of whom have already been waiting longer than the legal limit. As of July 1, 2019 there were 208 patients at the state hospital for restoration treatment.

Werthwein says the main reason for the waitlist is that “demand far exceeds capacity” of the number of beds available in the state hospital. Plans are in the works to add 110 beds by the end of 2021, as well as expand alternative programs like RISE.

The state has been consistently in violation of the time limit people are supposed to wait in jail until they can be admitted for restoration treatment.

Colorado Department of Human Services

For judges to feel comfortable referring patients to this network, though, there will also need to be funding and training. “We need the community to build up their resources and to accept everybody,” Butler explains. “A lot of providers in the community are hesitant to work with somebody who's out on bond for a felony crime.”

Along with streamlining the time requirements and expanding the evaluation and restoration options, the new law creates a tiered system to ensure that people who need treatment most get it fastest. It also puts a firm limit on the amount of time someone can spend in competency treatment. Previously, that limit was equivalent to the maximum sentence someone could receive for the crimes they were being charged with. But as Butler points out, that could mean defendants could serve time longer than the time of their actual sentence.

That's exactly what happened to Kyle the first time he was detained in Colorado. In August of 2016, he was arrested after what appeared to Patrice to be a confused attempt at breaking and entering his friend's garage to go get a bicycle that was actually his. But he was charged with a litany of serious burglary offenses. They thought they were "dealing with a true breaking-in-and-stealing-to-buy-drugs kind of person. But that’s a different category. I can see why — it’s not normal to go through somebody’s window," Patrice explains.

Because Kyle couldn't pass a competency exam and had to wait overdue times to get restoration, that charge resulted in nine months of detainment, two of which were at the state hospital. He finally pleaded guilty to a trespassing charge that demanded he serve no more than 180 days — but he had already far exceeded that time behind bars.

"There’s a pattern for people who go on to get these incompetency to proceed things,” Patrice says. They’re committing minor crimes out of confusion, desperation, or the influence of substances, like trespassing or sleeping in public buildings. “That’s not right, but it’s not eighteen-months-in-jail long, either.”

For Patrice, the new laws are a glimmer of hope. There’s a chance that Kyle’s felony charge will be demoted to a misdemeanor or dropped altogether, and Patrice believes that as long as he has support in stabilizing his life with housing and employment, he can stay out of trouble with the law. “Long term,” she says of her son, “I think if he gets out fairly soon, he’ll be fine. He’s gonna have the stigma, but his personality before this went down was so great, and he’s so charismatic, that he’s gonna make it.”

SB 222 directs the state to come up with a comprehensive plan to prevent people like Kyle from encountering the criminal justice system in the first place.

“If there had been better mental health treatment in the community, those folks would not have gotten caught up in the criminal justice system in the first place,” Nelson says. “It’s not just about custody and freedom, it’s about meeting their complex needs and how [we are] failing to do that as a society before they get swept up in the system.”