Guadalupe Briseño, better known as Lupe, tried to hide her nervousness. As the instigator of the strike, she knew that this day would end the standoff one way or another. Less than a week earlier, a fistfight had broken out along the picket line between at least one demonstrator and a manager at the flower farm, and a court had subsequently granted an injunction against the strikers. Briseño recognized the inevitable: With the courts ruling against the strike and additional violence likely, it was time to end the action. Still, she was determined not to let more than half a year of picketing conclude without a final act of civil disobedience: She and four other women would form a human barrier across the front gate of the Kitayama farm to prevent scabs from accessing the facility.

The women had come prepared. With the help of some of their husbands, Briseño, Mary Padilla, Martha del Real, Mary Sailes and Rachael Sandoval wrapped a thick metal chain around their waists and the front gateposts. Within minutes, they heard the wailing sirens of Weld County sheriff’s deputies barreling toward the flower farm in their patrol cars.

“Then all I could hear was the boom-boom-boom of their boots as they walked past us under the chain, wearing gas masks and carrying something like a long machine-gun rifle,” Briseño would later recall in an interview with University of Northern Colorado Hispanic Studies professor Priscilla Falcon. “The men — my husband, Jose; Rachael’s husband, Sam; Mary Padilla’s husband, Gavino — ran across the street when they saw the Weld County sheriff deputies with this tear-gassing machine.”

“They are going to try and kill you guys, forget it, let’s go!” yelled Briseño’s husband.“They are going to try and kill you guys, forget it, let’s go!”

tweet this

But the women refused to move, even after the boss of the flower farm, Ray Kitayama, arrived and told the sheriff’s deputies to cut the chain — which they did, though only near the fenceposts, so that the women were still chained together. Since this was a nonviolent protest, Briseño figured that the deputies would continue to cut the chains, allowing the women to go their own way. She was alarmed when one deputy pulled on a gas mask and advanced on the women carrying a machine that looked like an oversized insecticide dispenser.

A white mist of tear gas erupted from its nozzle, and the deputy moved the machine from side to side so that the gas completely covered the chained women. They collapsed to the ground together in a heap, wailing and coughing.

They realized then that the strike was truly over.

Fifty years have passed since the Kitayama Carnation strike ended, but its ramifications continue to be felt today, especially by Lupe Briseño, who still lives in Brighton. At a recent meeting at the Anythink Library there, the 85-year-old and dozens of others gathered in a conference room to share their memories of the strike.

“He wouldn’t give in and I wouldn’t give in, so it was going to be win or lose,” Briseño said of her former boss.

Rachael Sandoval, who was six months pregnant the day the women were tear-gassed, was asked if she was worried at the time. What was going through her mind when she decided to chain herself to the gate?

“We decided we needed to strike, then we got all chained up,” Sandoval replied. “That’s just how it was.”

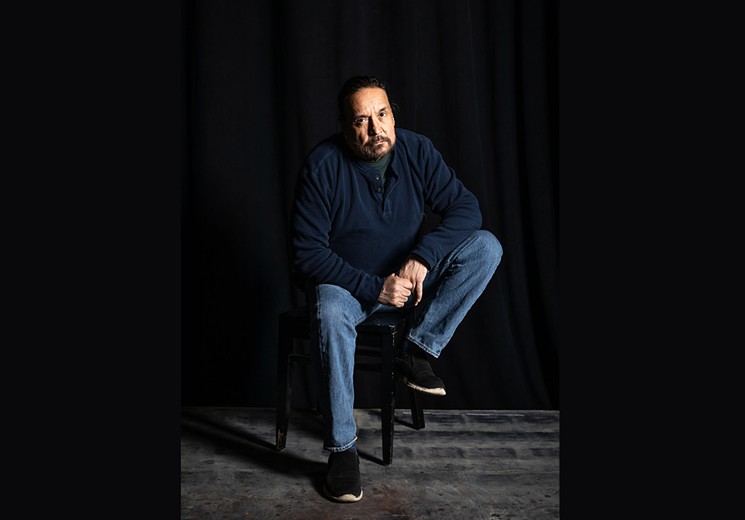

At this, a man in a blue beanie slapped his knee and exclaimed, “You act so casual, like, ‘Oh, we were cooking, and then we decided to get chained up and tear-gassed!’” It was Tony Garcia, executive artistic director at Su Teatro, the third-oldest Chicano theater in the country.

Sandoval chuckled, joining others who appreciated Garcia lightening the mood as these women, considered heroes by many in the room, related their somber story.

For months, Garcia had been hosting “story circles” to gather recollections of events that took place a half-century ago in Colorado. The research was in preparation for Chicano Power 1969! The Birth of a Movement, which Su Teatro will unveil on March 14. The production comprises a pair of one-act performances that commemorate the fiftieth anniversaries of two seminal events in 1969 that laid the foundation for the Chicano Movement in this country: the Kitayama Carnation strike and the West High School Blowouts (or walkouts). Both occurred just weeks before a Chicano youth conference convened in Denver — an event that became legendary in its own right.

“Those five weeks, from Kitayama to the youth conference, created the Chicano Movement and created change in the country,” Garcia told the group at the Brighton story circle, “and we’re all part of the legacy of those five weeks.”

Su Teatro is also a part of that legacy. Founded in 1972 by students at the University of Colorado at Denver, the theater is known for exploring questions of Chicano identity and taking an unflinching approach to political and cultural issues — including white supremacy and gentrification — that affect Hispanic communities in Colorado and beyond.

"Telling the story of this community has always been intrinsic in what we’re doing.”

tweet this

“Our first full production, in 1976, was on displacement of people in the west side, from Auraria, so telling the story of this community has always been intrinsic in what we’re doing,” Garcia recalls.

Over the decades, Su Teatro’s original productions have re-created important events of “El Movimiento,” or the Chicano Movement — a term that broadly refers to the civil-rights and cultural-empowerment movement among Mexican-Americans (and others who identify as Chicano) that began in the 1960s as a reaction to systemic racism in the United States and more than a hundred years’ worth of injustices, including land seized from Mexicans by white settlers in the West. Over time, the Chicano Movement encompassed efforts to protect farmworkers’ rights, including the United Farm Workers of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta in California, to create institutes for Chicano education, and to restore land grants in New Mexico, Texas and Colorado that were dishonored by the federal government and the states.

But as with all movements that span decades and various leaders and personalities, the history can get murky. What, for example, was the apex of the Chicano Movement in Colorado?

Garcia found himself debating that question with a friend in late 2017. At the time, he remembers, his answer was: “It had to have started with the West High Blowouts.”

“No, no!” the friend disagreed. “It was before then. It was Kitayama!”

Garcia was taken aback. He and one of his frequent collaborators, writer and composer Daniel Valdez, were already working on a play to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the West High Blowouts, when more than 150 students, most of them Hispanic, walked out of the Denver high school to protest racial injustices and discrimination by teachers. Now the scope of the production widened.

“We also realized we had to tell the story as a whole,” Garcia recalls. “These five weeks of intensive activism that transformed Colorado forever.”

The Kitayama Carnation strike may be remembered most for its violent end, but the demonstration actually began many months earlier, when Lupe Briseño decided that workers at the flower farm should band together to demand better wages and treatment.

The boss of the farm was one of the namesake founders of the powerful Kitayama Brothers Company. The four Kitayamas were a success story: Having been interned at Manzanar internment camp during WWII, in 1948 they formed a company that became the largest flower-growing operation in the country, beginning in Union City, California. In 1956, Ray Kitayama opened a sixty-unit greenhouse operation near Brighton.

While the local business community welcomed the jobs, some activists would later suggest that Ray Kitayama chose Brighton specifically to take advantage of cheap Mexican-American labor along Colorado’s Front Range — the kind of workers who wouldn’t complain about poor conditions.

After years of working as a migrant laborer, Briseño was hired on full-time at the Kitayama farm in early 1968, after her youngest child was old enough to attend grade school. On the farm, she was shocked to recognize a number of women she’d met when she first moved to the Brighton area in 1957; now they appeared sad and beaten down, shells of their former selves.

“The women were tired of long hours and poor working conditions, the lack of sanitary eating areas and low wages,” Briseño told UNC’s Falcon in the mid-’90s. “The women worked inside the nurseries on uncovered floors where dirt turned to mud, where the constant high humidity year-round produced several inches of water daily. Slipping and falling were common, as were colds, pneumonia, allergies and arthritic pain.”

Even as a newer employee, Briseño believed the workers should stand up and demand better treatment. In the spring of 1968, she organized a series of meetings to explore the idea of forming a union. Her efforts to keep the meetings secret failed; Kitayama found out about each one and attended the meetings himself.

“Myself, the women and men were offended. We concluded we were not toddlers, we can meet whenever we want,” Briseño recalled. “It was a police state. We were scared.”

Finally, at a meeting that wasn’t infiltrated by Kitayama or his managers, seventy workers from the Kitayama Carnation Farm formed the National Florist Workers Organization — NFWO for short — taking inspiration from the United Farm Workers (they even adopted the same eagle logo). The new union would later receive affiliate status from the UFW, a serious boost in legitimacy for the young organization.

Under Briseño’s leadership, the NFWO got to work, creating slogans for picket signs (“Unfair to Labor,” “We Want Job Rights”), obtaining an attorney to lead negotiating, documenting the business side of Kitayama’s operation and setting demands for the strike, including medical benefits for workers and wages based on seniority.

Throughout the process, Kitayama refused to negotiate in order to prevent a strike. And one Saturday in May 1968, when Briseño was at home making dinner, Kitayama and an assistant showed up at her front door carrying Briseño’s flower-cutting knife, hat and gloves.

“You are fired,” Kitayama said coolly.

Briseño’s response was not as collected: “This is not the end of it! If we win, we win, if we lose, we lose, but we’ll give you a good fight!”

That fight began officially on July 1, 1968, when the union voted to strike.

No one anticipated that the strike would last as long as it did. Day after day, the strikers would show up and picket in front of the entrance to Kitayama’s farm. But Kitayama dug in, hiring white teenagers from Brighton to replace the strikers, paying the new hires wages that were much higher than he’d been paying the others. But nearly all of the scabs left the job after realizing how arduous the work was.“This is not the end of it! If we win, we win, if we lose, we lose, but we’ll give you a good fight!”

tweet this

Brighton was split by the strike, and the division deepened as it wore on. By the end of 1968, the Briseños and other families were living on donations. Many strikers couldn’t get replacement jobs, because business owners in Brighton wouldn’t hire them.

Things came to a head one afternoon in January 1969, when Chuck Boomer, a supervisor in one of the greenhouses, approached Briseño at the plant’s entrance and shoved her. “I’m fed up with seeing you here!” he yelled.

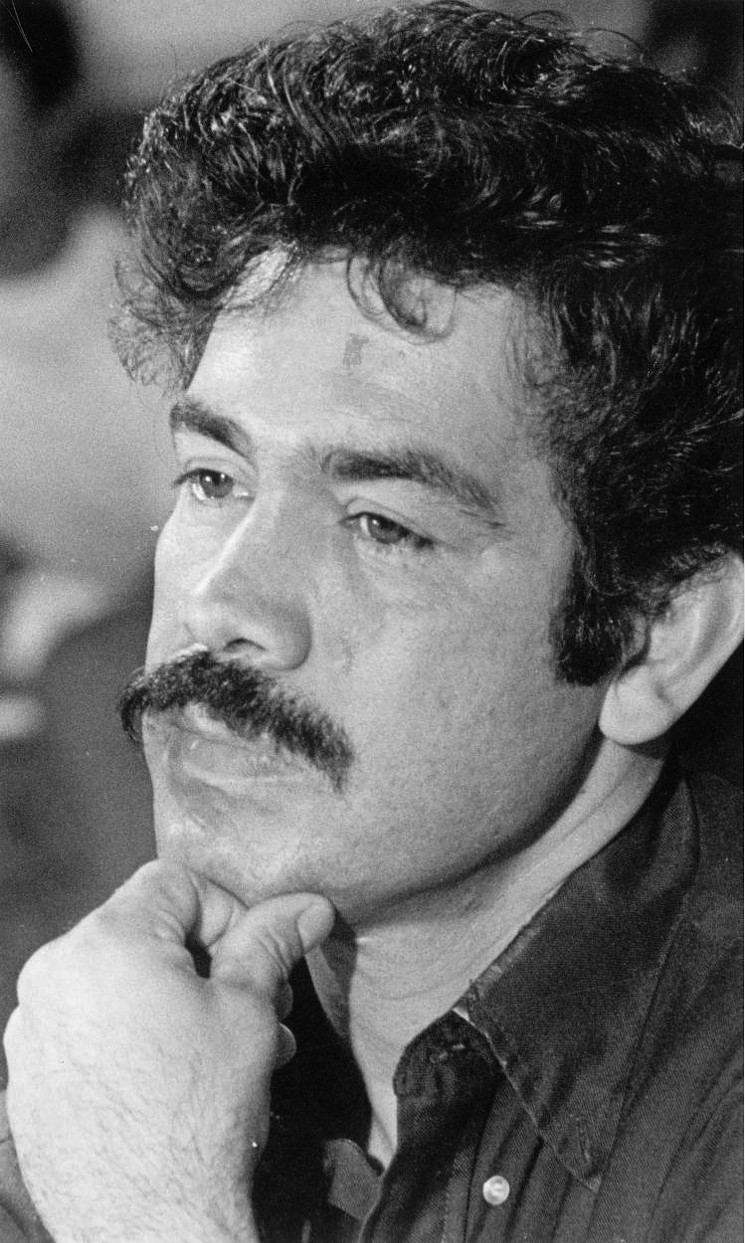

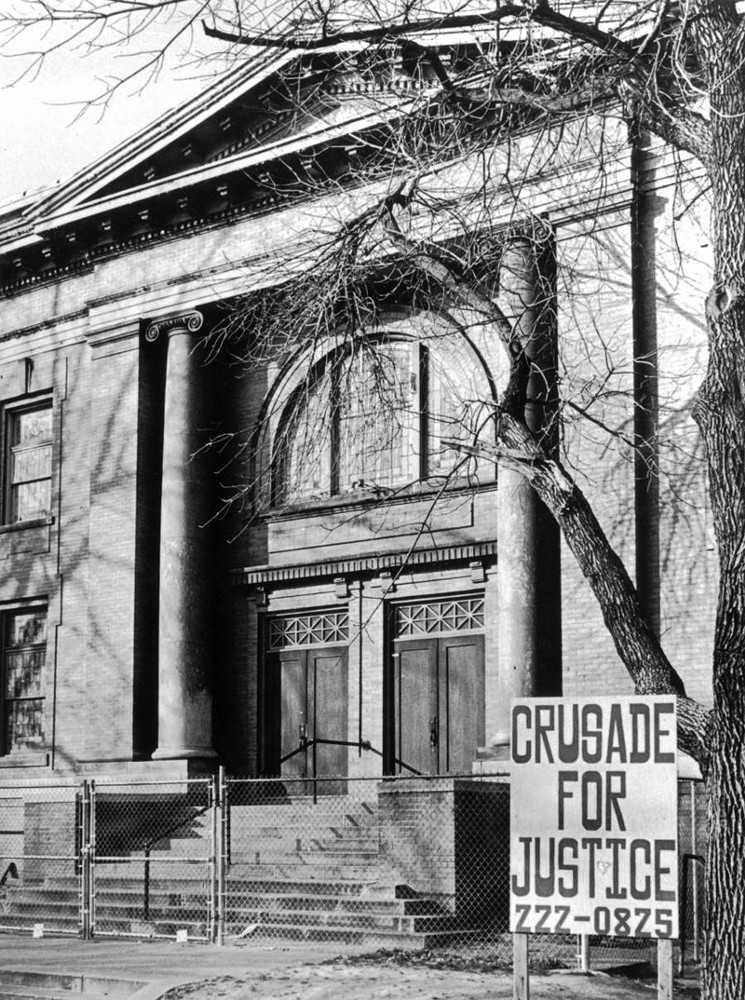

Alarmed, Briseño sent another striker to call the Crusade for Justice, a Denver civil-rights and Chicano-education organization founded four years earlier by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, a former boxer and nationally renowned leader of the Chicano Movement, to send backup.

Gonzales answered the call himself, coming to Brighton with a handful of other Crusade for Justice members. Boomer was still taunting the strikers when they arrived.

To this day, Briseño says she isn’t sure who threw the first punch (though it may have been Gonzales, given his background), but someone took Boomer out.

“Next thing I knew, Chuck Boomer was laying on the ground, knocked out. And it was [Crusade for Justice member] Ricardo Romero who was arrested for assault,” Briseño recalls.

Kitayama petitioned a county court judge to issue a temporary injunction against the strike on the grounds that it was endangering his employees. The injunction was granted on February 7.

By now, however, the NFWO had also concluded that the strike was dangerous — not for Kitayama’s employees, but for the picketers. The leaders had seen that Kitayama’s guards were armed, and worried that the next time there was a confrontation, guns might be used against them. Briseño and four other women decided that they would make a last bid for concessions with a dramatic demonstration on February 15.

Then came the tear gas. While the deputies watched, the husbands rushed over to cut the chains that still linked the women together, using their handkerchiefs to wipe off the white gas foaming on their faces.

“Through our veil of tears, you could not see our broken hearts,” Briseño said years later.

After that, conditions improved slightly, as did wages, at the Kitayama Carnation Farm — though Briseño was not a beneficiary. She and the other women who’d made their stand on February 15 were never rehired, and for years, they struggled to find any other work in Brighton.

“We didn’t enjoy the effects of the strike, but others did,” Briseño says. “But most important was that it woke up the community, especially young people.”

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, a key leader in the Chicano Movement in Colorado and nationwide, founded the Crusade for Justice.

Denver Public Library

During another story circle that Garcia organized at Su Teatro, Katie Lucero Segura recalled how she and many of her peers were never taught Spanish by their parents because they were shamed whenever they spoke it in public.

“If we spoke Spanish at school, they would make fun of us,” Segura said of her white classmates and teachers at Denver’s West High School in the late 1960s. “They also used to make us eat our burritos somewhere else.”

“Yeah, we felt that we were being disrespected all the time!” Garcia chimed in. In the late ’60s, he added, young Mexican-Americans were being drafted and sent off to fight the Vietnam War, routinely had their names anglicized by teachers, saw neighborhoods like Auraria being forcibly displaced, and distrusted the police in light of constant harassment and police shootings in minority neighborhoods.

“We felt like we were at war,” Garcia said before turning to the topic of the West High Blowouts. “Now, who was there on the day of the riot?”

Emanuel Martinez, a well-known artist who has painted politically provocative murals throughout Denver, recalled being at West High the day the demonstration started, on March 20, 1969 — not as a student, but as a member of the Crusade for Justice.

Martinez was one of a handful arrested on the first day, along with a female who “was fighting like hell. It took four policemen to get her into the paddy wagon,” he remembered. “Then, when we were all handcuffed, [the cops] sprayed Mace inside the paddy wagon from a small hole. It was terrible. But we were all eventually acquitted, because the films showed exactly what happened.”

The Crusade for Justice headquarters at 1567 Downing Street became a focal point for Chicano activism in Denver.

Denver Public Library

This was not the first complaint that Corky Gonzales and others at the Crusade had heard about this particular teacher. One student, Jeanie Perez, reported that Schafer routinely anglicized her surname to “Paris” just to taunt her. At a school where 38 percent of the students were Hispanic, Schafer had reportedly told his classes that “all Mexicans are stupid because their parents were stupid,” and “If you eat Mexican food, you’ll look like a Mexican.”

Gonzales, who was already preparing a youth conference to bring young Chicano activists together in late March, called for a meeting with the West High administration on February 27, where he related students’ complaints about Schafer and demanded the teacher’s dismissal.

The meeting ended with a promise that Schafer would be removed. “Good,” Gonzales told West administrators. “Because either you take care of it your way, or we’ll take care of it our way.”

But as days stretched to weeks, Schafer continued to teach at West. Finally, on March 19, several students told the Crusade for Justice that they planned to walk out of school; they wanted advice from the more seasoned activists about how to conduct their demonstration. The Crusade helped them create protest signs and spread leaflets alerting other students about the walkout the next day, March 20, that was scheduled to begin at exactly 9 a.m.

As the clock struck nine the next morning, approximately 150 students streamed out the front doors of West High School, hoisting signs declaring “Black and Brown United!,” “We Demand Better Schools!,” “Chicano Power!” and “Out with Schafer!”

The students listed their demands, which were printed in the West Side Recorder. Among them were the inclusion of Chicano history and literature in the school’s curriculum, the availability of bilingual education, the firing of Harry Schafer, and the expectation that no student participating in the walkout would be expelled or suspended.

The students marched to nearby Baker Middle School, then returned to West, where they were met by approximately thirty Denver Police Department officers in riot gear standing at the top of the school steps.“Because either you take care of it your way, or we’ll take care of it our way.”

tweet this

These officers were part of a new “Special Services Unit” that Police Chief George L. Seaton had created after assuming the post of Denver’s top cop in 1968. A hard-line law-and-order type, Seaton was jarred by the unrest that had recently taken hold across the country, including the 1967 Detroit riots and the 1968 Democratic National Convention demonstrations in Chicago. In a famous interview with the Denver Post in 1969, Seaton remarked that he thought protesters and organizations such as the Black Panthers were trying to “tear down the structure of the city and nation.”

Those concerns were reflected in a program Seaton had established at the start of 1969, bringing in the FBI to train the DPD in methods of riot and crowd control. Sixty DPD officers took part in the training, including the 31-member Special Services Unit, which was formally established on March 6; the West High demonstrations were among the unit’s first major deployments.

At first, the students participating in the walkout weren’t sure what to make of the riot-control cops. A brief shouting match ensued between the officers and Gonzales — who was there with his own bullhorn — before the cops ordered the crowd to relocate from the front steps of the high school to the Sunken Gardens across the street.

According to witnesses, and as shown by video footage taken at the time, the students closest to the police on the top rows of the steps tried to back away but were blocked by students on the stairs behind them; many students in the rear of the crowd would later claim that they didn’t hear the order to move. When police officers pressed up against the first rows of students, pushing them with their batons, some students fell backwards down the stairs. This caused a few students to angrily strike back against the police. And that was all the police needed to unleash their full force.

Officers began attacking the crowd with batons and Mace. More students began fighting back, including a group that chased a lone policeman into the Sunken Gardens, swarmed over him, then stole his police helmet after he was knocked unconscious.

The riot quickly spread. The cops chased a group of students into the Lincoln Park neighborhood, where they took refuge in the Denver Inner City Parish on Mariposa Street. After other demonstrators, including Emanuel Martinez, were arrested, some students congregated outside the city jail, shouting, “Viva la raza! Viva la raza!” loud enough that arrestees could hear the chants from inside their jail cells.

By the time Corky Gonzales spoke to demonstrators outside the Inner City Parish, urging them to go home, 25 police vehicles had been damaged and 17 policemen injured.

Word about the walkout and violence spread throughout Denver. The next day, a second demonstration was held at West High School, this time with about 700 participants, only half of them students. The protest had captured the attention of the whole city, illuminating a host of grievances both in and outside of the Chicano community.

Violence again erupted in the Lincoln Park neighborhood after some young people threw bottles and rocks at police. By mid-afternoon, most demonstrators had gone home, but not before riot-control police were ordered to load shotguns with birdshot and to make sure to fire low — at feet and legs — so as to not kill anyone.

“That function was to protect laws and property and maintain order to see that there was no violence committed,” a Denver police captain told the press. “It was to make sure that the kids in school were not disrupted to the extent that they could not continue their studies. And of course our role is not to side in, or with, anyone’s philosophy or demonstration. Our role is to see that all demonstrations are kept orderly and lawful and that everyone’s rights are protected.”

Corky Gonzales saw things differently. “There are many reasons for it happening,” he said at his own press conference. “And it’s been developing over the years. The young people, especially the Chicano groups across the nation, are starting to recognize the inequities of the school system and [starting] to identify with themselves and their contributions and heritage and culture. I hope it’s not an isolated incident. It’s happening across the Southwest. It’s our feeling that this was a minor eruption — people airing their grievances and [looking for] meaningful gains, not only for themselves, but also their community.”

Gonzales added that he believed the violence on the first day of the walkouts was unequivocally the police’s fault. He was less specific about the second day. “There was antagonism of having policemen prepared for battle, so to speak. The reaction created a confrontation,” he said.

“But the answer, as I see it,” he concluded, “is community control, community involvement, taking part in making decisions governing our own lives instead of being controlled by absentee school boards that live in the rich parts of town.”

The West High students did secure a win: Racist social studies teacher Harry Schafer was transferred to a different school. But the biggest result of the West High Blowouts was that it galvanized the national youth conference that Gonzales had already been planning for March 23, 1969.

Organizers had estimated that 300 people would attend the National Youth and Liberation Conference. But 1,500 youth came to Denver from across Colorado, Texas, Oregon, California, Washington, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico; Puerto Rican youth traveled to Colorado from the Midwest and Northeast. While the conference included a number of artistic performances and symposiums, its most consequential creation was the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán. This manifesto began with a poem introduced by Alurista (Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia) in which the poet defined Aztlán not just as land comprising Mexico and Mexican territories annexed by the United States, but a place where modern-day Chicanos could share a sense of nationalism and self-determination. The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán laid out a number of goals that changed the course of the Chicano Movement: unity, economic control, education relative to Chicanos and Chicanas, strengthening cultural values and political power.

The Chicano youth conference in Denver in March 1969 presented a new, clarified vision for the entire movement.

Students take to the streets after walking out of West High School on March 20, 1969.

Denver Public Library

That influence can be seen all over Denver: in the public murals by artists like Martinez, in the Denver branch library named after Gonzales, at the La Alma Park and Recreation Center, at César Chávez Park. Many of the wishes of those West High students in 1969 have been realized: Chicano history books are included in libraries, bilingual education options are available in public schools, and school boards include prominent Hispanic voices.

“And you have Metropolitan State University of Denver, which I’d argue is a Hispanic-serving institute,” says Garcia. “They have a Chicano Studies department, which I teach in. [The University of Colorado Denver] has an Ethnic Studies department.” But the advances come with a loss: Both schools are located on the Auraria campus, whose construction displaced the majority-Hispanic neighborhood there.

“Federico Peña was a really big breakthrough,” Garcia continues, describing the events of 1969 as a catalyst for Denver’s election of a Hispanic mayor fourteen years later.

Peña doesn’t disagree.

“When I arrived in Denver in 1973, all of those events [of 1969] were retold to me, and, to be sure, I think they had a dramatic impact on educating the Latino community in Denver back in those days...and motivating Latinos to start speaking out, to have more confidence in filing lawsuits and otherwise take action to fight discrimination,” Peña says.

“I remember Richard Castro, who was elected as the youngest legislator in the history of Colorado, said that he was part of the West walkouts,” the former mayor continues. “And he used to tell me all the stories of when he and others helped organize the walkout. Then there were other people like Paul Sandoval and the Benavidezes, who all came from that generation and became public officials, so there’s no question that what happened in 1969 awakened Latinos, got them to register to vote, and inspired them to get involved in the political process. When I ran for mayor in ’82, the Latino population was 18 percent in Denver. By that time, people were already accustomed to voting, had already elected a number of Latino legislators and city council members, and so people had realized their vote could count and they could make a difference.”

Garcia says he regularly has conversations with younger people, including students who’ve interned at Su Teatro, who take inspiration from the activism of previous generations. “So many young people today will say, ‘My parents were involved’ or ‘My grandparents were involved’ in the movement,” he points out.

Priscilla Falcon was one of them. At the time of the Kitayama Carnation strike, she was a seventeen-year-old freshman at the University of Colorado at Boulder, and traveled with other students to Brighton to support the picketers.

“When I would see Lupe [Briseño], it was like seeing a hero for the first time,” she recalls. “Because back in the day, Mexican people were made to be subservient. And at the time, the Chicano Movement was also very male-dominated. But going to Brighton and seeing these women who are advocates and know how to explain their social conditions, it was really exciting. It was so empowering.”“So many young people today will say, ‘My parents were involved’ or ‘My grandparents were involved’ in the movement.”

tweet this

That empowerment propelled Falcon through some turbulent years in the Chicano Movement. In 1972, her husband, Ricardo — a prominent Chicano Movement leader — was shot and killed by a hostile gas station owner while en route to a convention of La Raza Unida in New Mexico. Lupe Briseño organized Ricardo’s funeral.

Colorado’s Chicano Movement took another hit in 1974, Falcon says, “when you had the Los Seis de Boulder situation.”

Within a two-day span that May, six young Chicano and Chicana activists were murdered in a pair of car bombings in Boulder. The crimes were never solved; to this day, many believe the activists were assassinated by the federal government, since the bombings took place during the era of the FBI’s vast surveillance program known as COINTELPRO. (Su Teatro did a production in 2014 to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the Los Seis de Boulder bombings.)

“After that, many people became fearful that they could be the next target of the government,” Falcon says. “So there were peaks and valleys in the movement. If you’re looking at the activism among the student population, I would definitely say that a peak was 1970, with the Chicano moratorium in California, where 3,000 folks came, and after that I think we entered into a repressive period where there was a lot of COINTELPRO stuff going on.”

But the events in metro Denver in 1969 were the real catalyst for awakening and inspiring an entire generation of activists like herself, Falcon says.

Garcia has been trying to reach as many of that generation of activists as possible to guarantee the historic accuracy of Chicano Power 1969!’s two one-acts: “The War of the Flowers” and “Fire in the Streets.” But the story circles have given him almost too much to work with.

“We have so much material that we feel like the next stage is to turn these into two full-length plays,” he says. “The songs will continue to evolve as well. This is something that’s going to be around with us for a while.”

Bringing the Kitayama Carnation strike and West High School Blowouts to the stage is Garcia’s way of making sure that long-gone events aren’t forgotten, especially since their lessons remain so relevant — and because original participants like Lupe Briseño are still around to tell the story.

“I think it’s very nice that young people are interested and are using these stories to see the differences between fifty years ago and now,” Briseño says. “Young people will not let it happen again. That is the difference.”

Chicano Power 1969! The Birth of a Movement opens Thursday, March 14, at Su Teatro Cultural & Performing Arts Center, 721 Santa Fe Drive. For ticket information, go to suteatro.org.