If you grew up in Denver, certain names mean something to you that probably don’t mean a thing to the transplants living next door. Denver newcomers might have seen that Casa Bonita episode of South Park, but chances are good that they never visited Celebrity Sports Center, or know that Cinderella City was a shopping mall, or ever heard of the Gum Tree.

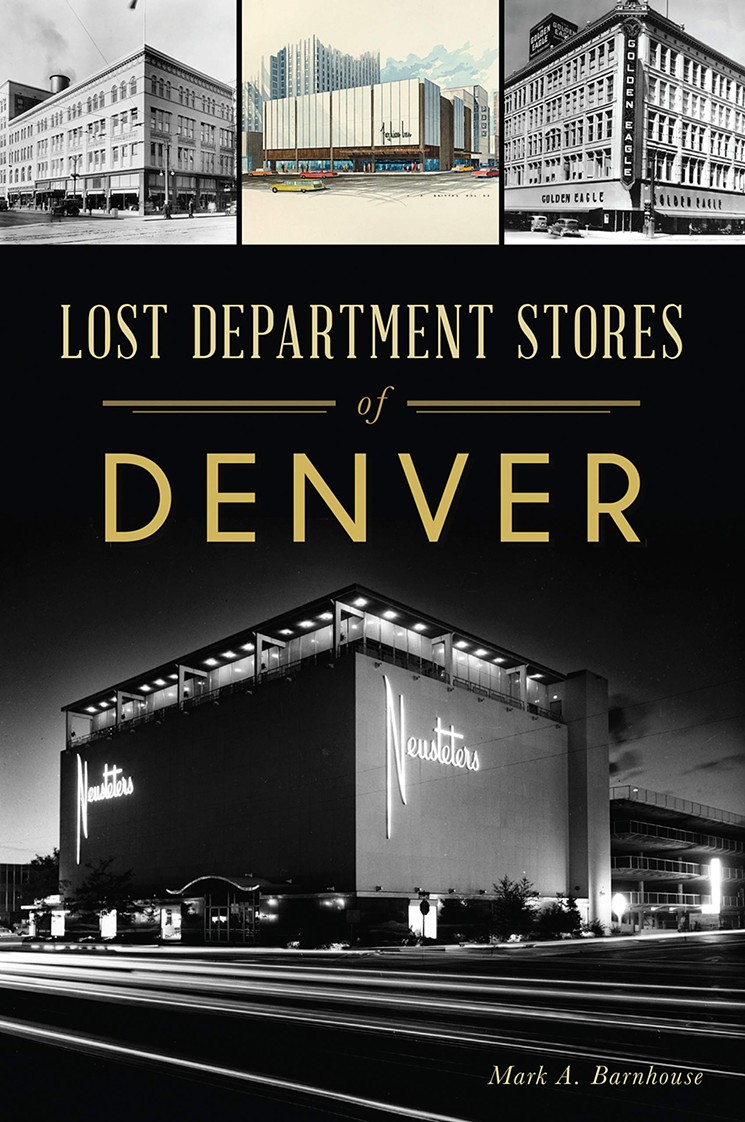

Mark Barnhouse remembers, as his many books on Denver history prove. Barnhouse will be at West Side Books on Friday, May 10, to talk about his latest, Lost Department Stores of Denver, and show photos of old-time Denver. Westword caught up with Barnhouse to talk about what's in store at that event.

Westword: When you do appearances like this, do you read, discuss the book in a more general sense, show the audience photos as reference? What's your approach to these public presentations of your very visual work?

Mark Barnhouse: I speak extemporaneously rather than read from the book. I always include a slideshow, because people really like seeing how these things used to look, and over the years I’ve built up a large library of images. At the end, particularly when I’m talking about department stores, I always ask people about their memories, and if they’ve ever worked for any of the stores I’ve talked about. Inevitably, several hands go up. People also remember ice skating at Zeckendorf Plaza in front of May D&F, and dressing up to eat at the Denver Dry Goods Company Tea Room. I learn something every time, because people tell me stories; at one event I even had two people who were descendants of the “merchant princes” whose stories I had just told. Department stores are a surprisingly emotional topic.

What got you into Denver's retail history?

From the time I was a small child, I found stores and malls interesting, and I can’t really say why. I have a particular childhood memory of going with my mother to the Denver’s Tea Room for “Breakfast With Santa” when I was about seven years old. When I was a teenager I used to go downtown a lot, and I always spent time on 16th Street, going into the department stores, the old Woolworth (the world’s largest), buying records at Musicland and books at Chapter 1 on Welton Street. This was long before downtown became a popular teen hangout; I was a weird kid.

When I decided to go to college, I took a class from Thomas “Dr. Colorado” Noel at UCD. He asked the class to pick a place and write about it. It could be anywhere in Colorado, but I chose a place a ten-minute walk away from the campus, 16th Street. I kept researching over the years, until I had amassed a couple of drawers of microfilm printouts on the extremely well-documented history of the street that was “Denver’s Main Street” from the 1880s through the post-World War II period. I had this idea that 16th Street needed a book written about it, because years ago, Dr. Noel had written a book (Denver's Larimer Street) on Denver’s original “Main Street," and I thought 16th needed the same kind of treatment. My first book, Denver’s Sixteenth Street, was not exactly what I had originally envisioned, due to the publisher’s standard photo-heavy format, but I’m still happy with that book today. Writing books about department stores specifically stemmed from all of that early work.

Since you mention 16th Street, what are your thoughts on the new proposal to change the face of that particular thoroughfare all over again?

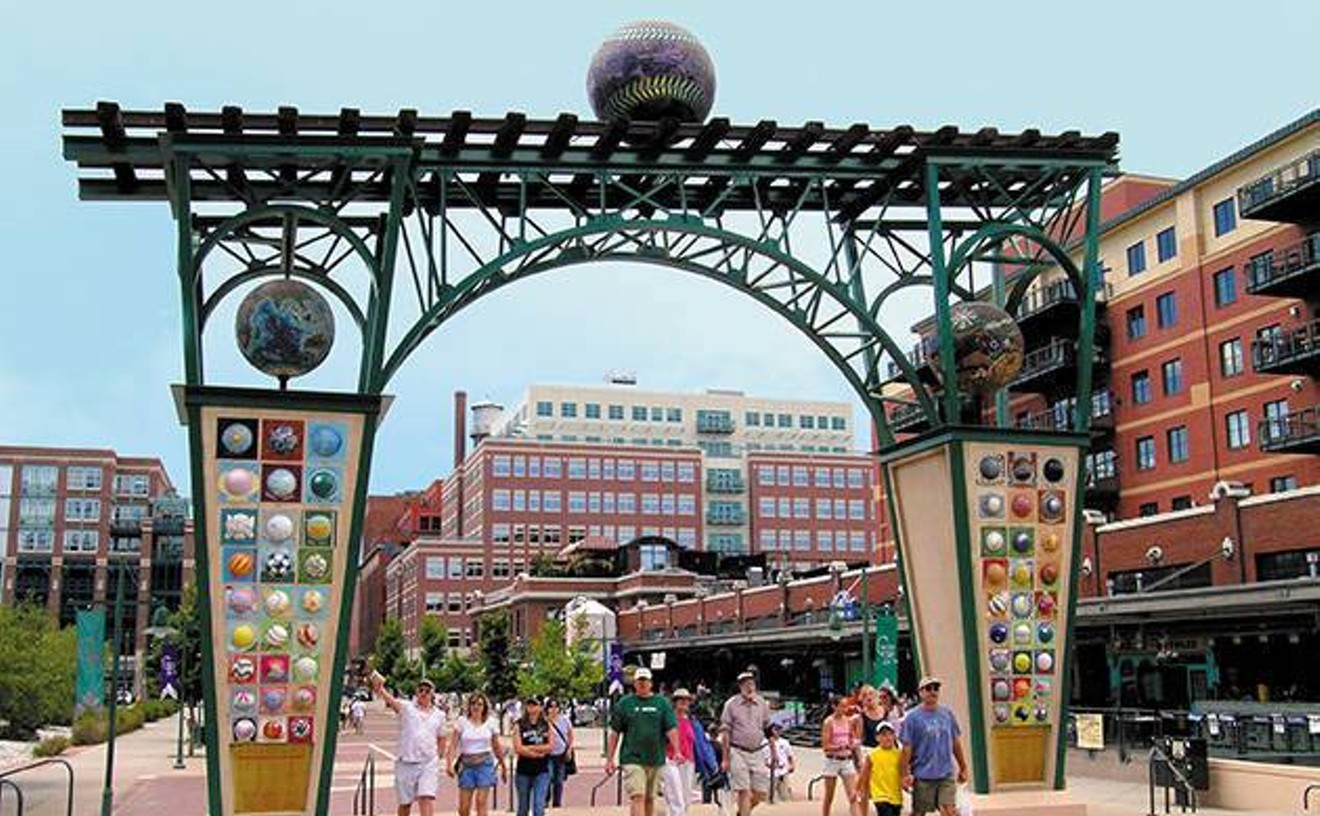

I looked online last week at the city’s 16th Street documents. It’s clear that there are many aspects of the original mall design that have not worn as well as the community would have liked. Most of the trees are in poor shape. Lampposts are missing. The fountains have been turned off for years. People have stopped using the center median in ways originally envisioned, as places to have conversations while sitting on the benches or eating lunch. Various modifications and additions over the years have degraded the design. And, of course, there’s the problem of the bus lanes and their million-dollar annual repair bills. My hope is that the mall will get rebuilt in ways that honor the original design, adhering to it as closely as possible. I don’t think that “doing nothing” is a viable option. I would particularly be sorry to see the rattlesnake pattern made by the three shades of granite disappear — it’s part of the mall’s essential character.

I am adamantly not in favor of removing the shuttle buses — without those, the mall would not work at all, and might as well be converted back to a normal downtown street. People who say, “Let’s move those to 17th and 15th so the mall can be entirely pedestrian” miss the point that other malls that are entirely pedestrian —Boulder’s Pearl Street being a major exception, but it’s only four blocks long — have failed. Pedestrian malls were all the rage in planning circles for about three decades, and most of them are now gone. The Sixteenth Street Transitway/Mall, as it was originally called by RTD, has been successful because the shuttle buses give it a purpose and allow people to move along at either a slow or a faster pace, and to feel reasonably safe. With no shuttle buses, the overall use declines, and people don’t feel as safe. Having led walking tours of 16th for Doors Open Denver for several years, I know that not everyone feels safe there, particularly in the upper and central blocks. Some of that fear is justified, but our local TV stations love to make it sound worse than it is. It is an urban environment, and it feels safer to me than parts of San Francisco that I’ve visited, certainly. Will it ever be as safe as people would like? No, but as long as you keep your wits about you and your eyes open, you don’t have to worry too much.

You grew up in Denver. Where in town did you live? How has that neighborhood changed over the years?

I grew up across the street from what was then called Merrill Jr. High School, now Middle School. We did not call the neighborhood as it is called now — “Cory-Merrill” — but simply “southeast Denver.” Mostly post-war ranch houses, and on our block mostly wood-frame construction rather than brick. Despite the modest houses, growing up in the neighborhood gave me a love of architecture. I attended Cory Elementary, one of the DPS’s best mid-century modern schools (Victor Hornbein was the architect); then Merrill, designed by Temple Buell; and finally, South High, that marvelous Romanesque Revival design by Fisher and Fisher. Today Cory-Merrill is nearly unrecognizable. Due to its relative nearness to Cherry Creek, Bonnie Brae and Belcaro, it has gone decidedly upscale, with some blocks almost entirely consisting of huge, faux-Mediterranean villas or faux-Modern boxes replacing the old, simple ranches. The house I grew up in is still there; I check every time I’m near it. My parents would not be able to buy into that neighborhood today.

You've also written about northwest Denver; talk a little bit about the massive changes to that part of town, especially in the past quarter-century.

I’m part of those changes, having chosen to live in what the city calls West Highland in 2001 when we decided to buy a house. I had lived in Capitol Hill previously, in a high-rise condo near King Soopers, and was tired of the noise. We bought our house from an older Hispanic couple who had owned it since 1969, raising six children. I was familiar with the neighborhood, as my grandmother had moved into what was then called Eden Manor, the high-rise for seniors at 32nd and Julian, in 1976. We liked it because it was a lot quieter than Cap Hill, though that has changed as the demographic has shifted younger. We chose the area for another reason, the one that many others have had: It was charming — it still is, despite the best efforts of residential and commercial developers to destroy that charm.

In the first decade, we loved living here, and felt that we were part of a community. When Denver got hit with three feet of snow on St. Patrick’s Day in 2003, no one could go to work for three days. A neighbor up the block knocked on everyone’s doors to not only make sure they were all right, but also to invite everyone to an impromptu block party that evening in her house. It’s hard to imagine that happening now, although we still have a number of neighbors we truly value. Most of the developers who have “discovered” these neighborhoods don’t live here. They live in Highlands Ranch or Centennial or Greenwood Village, and I view them as “colonizers" — people who come into an area and mine it for resources, the “resource” being land near downtown. They do not care about the quality of what they build, nor do they care whether the architecture of what they build respects what is there already. And then there’s the ecological argument: People who destroy houses to build new ones are destroying decades of “stored energy,” and spending a lot of new energy to do it.

Some parts of northwest Denver have lost nearly everything, particularly Jefferson Park. I testified at the Denver Landmarks Preservation Commission hearing on the Anderson House, which our developer-friendly city council refused to landmark despite its architectural importance to its immediate vicinity; what was built in its place looks like some first-year architecture student with some software designed it in about five minutes. These 3,000-square-foot houses with three people in them are no more dense than the 950-square-foot houses that had stood there previously. It’s all so shortsighted.

I've heard some people talk about the turning point — for good or for bad — being the one-two punch of the revitalization of 32nd and Lowell and the closure of the original Elitch's. What's your take?

Every area changes over time. As for the one-two punch idea, perhaps there is something to that, but I think the changes would have happened even with Elitch’s still in its original location — maybe not on the blocks closest to it, because roller coasters are noisy neighbors, but everywhere else in northwest Denver, certainly. In the 1970s, it was Washington Park’s turn to have people come in — that neighborhood used to be more mixed than it is now, with Gates Rubber employees alongside professionals. In the 1980s, people with money discovered Platt Park. For people subsequently priced out of those areas but who still wanted to live near downtown, northwestern Denver was the logical next place to go, beginning in the 1990s. Individuals made decisions that were right for themselves (I include myself here) but were not necessarily good for the people who had long lived in these places. And now we see the same forces at work in areas southwest of downtown, and of course Five Points and other northeast neighborhoods. It’s a tough discussion, because no one wants to feel like they’re the villain.

When talking about this part of town, terminology is important. There are those who are resentful when people, whether they live here or in other parts of town, call it “the Highlands.” Yet historically, it was the Town of Highlands before it was part of Denver. It was established as an elite suburb, consciously setting itself apart from sinful, dirty Denver, with its smelters, saloons and houses of prostitution, and it appealed greatly to white Protestants who appreciated the fact that obtaining a license to serve liquor was so prohibitively expensive that the town had no saloons at all. It incorporated in 1875 and merged with Denver in 1896 after the Panic of 1893 destroyed its ability to maintain itself as a municipality.

It became part of “North Denver,” a name that had originally applied to only the Denver neighborhoods east of Zuni, but was then applied to the whole area formerly encompassing the towns of Highlands and Berkeley, and other areas. As the former Highlands transitioned into North Denver, with Italian immigrants and, later, Hispanic/Latino people replacing the earlier groups, people stopped using the term “Highlands.” Instead they called themselves “Northsiders,” people who lived in North Denver. When the area began to shift in the 1990s, the name Highlands — officially, Highland and West Highland, with no final “s” on city maps — came back. Both terms can be used, depending on the conversation — there’s no reason that people have to align themselves with one name or the other, because both have a long history. I do wish people would call the neighborhoods Highland and West Highland, rather than “the” Highlands, like “the Ukraine.” We no longer put “the” in front of Ukraine, and we don’t say “the Park Hill.” But maybe that’s just my own peculiar opinion.

Speaking of neighborhoods transitioning, how do the changes in RiNo and Five Points strike you, in terms of both history and cultural loss? What's your take, as a historian, on gentrification and its effects?

That’s definitely a hot-button question, and I’m not sure if I can speak to it the way that those displaced residents can. It’s their story, not mine. I’m just someone living in a different part of town, not a longtime resident of a place like Five Points who is feeling the pain of seeing his community destroyed. In a way, it’s not unlike what DURA did to the residents of Auraria in the late 1960s and early 1970s so they could build the college campus: They were displaced by fiat. The main difference now is that private development, aided by city policies designed to benefit private developers, is doing the dirty work. It’s more subtle than what DURA did to Auraria, but no less destructive.

Of course, you are really talking about two distinct places. When I think of RiNo, I think not so much of Five Points, which is centered on Welton and is mostly residential except for what is on Welton itself, but of the industrial buildings along Brighton Boulevard and across the tracks along Blake, Market and Larimer. That old warehouses have been repurposed is not necessarily a bad thing, but when longtime residents on adjacent streets see their rent double or triple, forcing them to move to wherever they can afford, creating a diaspora, that’s a terrible way to run a city.

This country has a long history of destroying communities that aren’t part of the white middle or upper-middle class — Robert Moses’s carving freeways through New York comes to mind. He destroyed whole neighborhoods, not unlike what CDOT did when it routed I-70 through the northern parts of the city in the 1950s and 1960s without consulting the affected residents. Denver has always been developer-friendly; even Robert W. Speer, widely remembered as one of the most effective mayors we ever had, was a developer, and pals with other developers. Nothing has changed in the past century (Speer died in 1918). Money talks louder than constituents.

If you could bring one thing from Denver history back, what would it be?

On my wall I have a framed, highly detailed map of downtown Denver from the late 1930s. The streets are lined with shops, restaurants, theaters and all sorts of businesses — not just 16th, but every street between 14th and 18th, and all of the side streets, as well. Almost nothing had yet been demolished to create parking. The variety of shops and services on those streets blows my mind when I compare it to those same streets today. You see the old photos of people shopping downtown, and the sidewalks are crowded.

These aren’t like the crowds on 16th today, mostly people out for a good time. We live in a world where everything has been commoditized, and I would dearly love to see a Denver where people rode public transportation downtown to shop in locally owned stores, rather than doing their shopping online in their pajamas. But that’s never going to happen. Time doesn’t flow backward.

Mark Barnhouse will be at West Side Books, 3434 West 32nd Avenue, at 6 p.m. Friday, May 10. Admission is free; find more on the West Side Books Facebook page.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]