Kneebody has had many labels thrown at it, but none seem to fit. Just the same, the members of the transcontinental quintet (saxophonist Ben Wendel, keyboardist Adam Benjamin, drummer Nate Wood and Denver natives, trumpeter Shane Endsley and bassist Kaveh Rastegar) haven't exactly gone out of their way to make it easy for folks to pin down their shapeshifting sound, which is rooted in jazz, funk and rock.

See also: The best jazz shows in Denver in October

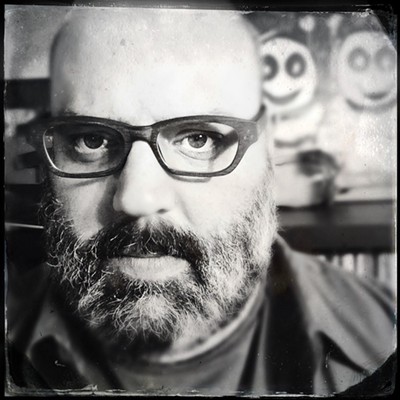

In advance of this Saturday night's show at Dazzle, we spoke Rastegar about the band's new album, The Line (released last month on Concord), how he and Endsley met in Denver, the act's name and the thirty-something musical cues the guys have developed that allows each player to tweak nearly any element of any given song.

Westword: The Line is your fourth studio album and the first on Concord. It sounds like it was a bit different making this record versus others? You did your others album in-house, right?

Kaveh Rastegar: Yeah. Exactly. We had always done our records... The band has always had a DIY kind of thing, where things have been in-house on our own terms, for whatever it's worth. Our drummer Nate is a great engineer, as well. He would always engineer tracks and mix our records. That was always really great, but then it was always such a burden on him. So it's just nice to have the luxury to be in a great studio like Sunset Sound and just kind of have it blocked out for a few days and then have another engineer -- this great engineer named Todd Burke tracked the album.

Then our friend Todd Sickafoose mixed the record. He's a great bassist, a great composer and also a great engineer. So that all around was just awesome to have them just working on stuff and doing their job. And also we had a Chris Dunn, who's our friend at Concord, as kind of like the extra set of ears who helped out to produce the record, which really helped things and give some perspective on some things that we couldn't really come up with at the moment. It all went really well. We just banged out the record really fast, actually, which was pretty cool.

In a few days, right?

Exactly.

Is that kind of normal for you guys to bang out a record pretty fast?

I guess we have kind of done things differently for each album. And I'd say each album is kind of like... It's like when you're a live band like we are, where we have this live show that we feel really strongly about, and it just feels really good live, and the songs are really complete and everything. Sometimes you can feel like that element can be lost in a studio album that you can do over how every many weeks it is. And when you go in the studio, a big part of how great that can be is getting amazing sound, and then sometimes overdubbing or making sections sound more epic, or whatever it is, whatever it need be.

This I think was a really good example... These songs are really strong, like they're just great songs on their own if you play them. I think it's a good example of how we play live. You can hear how we play. You can hear how the band sounds like. Just the tones are all really great, and Todd makes it really great.

It was pretty funny, actually, because there was that band Band of Horses next to us in the studio. They were in the next studio over with Glyn Johns, I think, doing their latest record. There's a basketball hoop and a little courtyard, and we'd be out there shooting hoops, and we'd chat with those guys. Those guys are really nice guys. A friend of mine played in that band. So we had stuff to talk about. It was funny. They were there for three months working on their record. For our record, we were there in the studio for two days. It's just funny how that works. It's obviously totally different music, and if we had been in there for three months, I don't know, maybe our album would sound like Face Value by Phil Collins or something.

Would you say it's the best representation of your live sound so far?

From a studio album, totally. We've been putting out live albums on our own for the last six or seven years. But on this one, the tones are really great, and the playing is really great. And there isn't much overdubbing at all. Maybe a couple of little things here and there. There's a track that I did that's like three layers of basses, and so that's more of an overdub thing. There's very little overdubbing. It's just mostly the band playing.

Are you guys still approaching songwriting the same way, where someone will bring in a song and you guys will just all learn it by ear? You don't really do any sort of lead sheets or that kind of thing, right?

Yeah. We don't do any of that. It's kind of just very aural. Everybody composes. Like everybody has their own composing voice, and everybody has their own different style. Like Ben Wendel, our sax player, his songs tend to be very developed when he brings them it. So he'll have parts pretty much worked out down to drum beats and stuff, and then, he'll have counter-melodies and whatever else going on. It depends on how involved it is, he'll write the song out and then just teach us, like he'll play a part from his lead sheet.

We never read our stuff because if you commit to memory, you just know it. We have all played in rock bands, and I still do. That's just, for me, the best way to internalize and get the music happening. If you can get away from the lead sheet as soon as possible, you can kind of learn the songs, and that keeps everything fresh, and it keeps everything internalized.

There's a song of mine on the album called 'Pushed Away." That was a song I had written on computers, just on Logic. I made a demo, and then I sung I a melody over the top of it. It was guitar, bass and drums. I taught everybody their parts, and then when it came time to do the melodies, the horn players just transcribed what I sung over the top. So that's kind of the vibe of that song. It just depends. But it's always taught.

Some of the songs you guys do sound pretty challenging. It sounds like it would be tricky to memorize all that stuff with all sorts of changes and that kind of thing. Is it ever really challenging for you?

It can be totally challenging. It's also an exercise in patience, too. Some songs are quicker. Some songs require less of certain people. Like there's that song "Still Play": There's a super long melody and just tons of notes, and it goes on forever. I think that one just takes longer for the people who play that melody to just internalize. Ben would play a chunk, and then you'd just learn that chunk. Then you'd learn the next chunk, and the next chunk, and just build it that way.

It sounded like a really complicated head.

Yeah. Totally. The band is kind of like a workshop in all that stuff, too. It's like any time I finish a Kneebody tour, I feel like my brain is so much stronger. You're just like in that head space of so much listening going on and so much internalization. So it's one of those kind of things where you feel like you've been on some sort of conditioning retreat or whatever it is.

Do you guys still do the cues when you're playing live?

Absolutely. We always do that. We have this cueing language that we've come up with over the years to kind of make the music move along if it needs to, and to make things change and to makes things happen. So, yeah, we definitely use that live a lot. And then on the album you can hear a little bit of it. There are sections where somebody will be taking a solo and you can hear somebody play the cue that means to go on. We definitely do a lot of that stuff live, which is always a lot of fun.

How many different cues to you guys have?

You know, we counted them at one point, and I can't remember, It's up in the thirties. Like the very first one was something that Shane came up with on one of his songs. Shane used to play with Steve Coleman and the Five Elements.

Yeah. That's where he got the idea from, right?

Yeah, I think you could fairly say that. Steve would do a lot of that. Shane could explain it better. But he would do things where the music would... He would, in the middle of something, start playing a phrase from a different part of the song and everyone would have to jump into it. So that whole idea of everyone listening really intently and being ready to go anywhere at any time was something that happened a lot.

Shane wrote a song a long time ago that we still play a lot called "The Slip." That song has just two sections, and they just cue back and forth. They have cues that make you go to the next section and the next cue is a cue that makes you stop, and then go on to the next section. The cue that makes you stop is something that we started using on different songs.

Then we stared saying, "Wouldn't it be cool if we could have things get faster." So we came up with a cue that did that. And, "Wouldn't it be cool if we could just make a tempo happen rather than gradually go faster or gradually go slower?" So we made a cue that did that. Now it's to the point where each person in the band has their own musical name. Like Nate is one tone -- concert B. Then I'm D-G. Adam is D-G-F. It goes on and on.

So it's like you could play people things, like, "Nate do this" or "Nate stop." Or "Kaveh stop," or "everybody stop and start." There are looping cues. And it's not to say that this stuff is always going on, but it's just basically like vocabulary that we all have at our fingertips, where we can just modulate the music if you want to.

As writers, too, we can write music that's kind of open-ended knowing that we can do these cues to move around within the music. Sometimes the music is very closed-ended, or it's very through composed, and there's never any cueing going on. They're just kind of devices to help you move around.

I would imagine knowing the tunes is one thing, but having to keep a keen ear out for the cues, too, that has to be tricky as well.

Oh man, it can be crazy. It's like a language. It's also like a language where you miss your people... it's totally about communication. Somebody plays a cue and you don't hear it, or two people play a cue at the same time and everyone has to do everything again, you know, look at each other and differ.

Has the band's approach to playing changed at all since you started ten years ago?

Yeah. I would say, over the years, the music... Everybody plays with lots of different other artists, too, so that's always been an interesting thing to bring back and pour it into the band. I remember when we started, we were more of a rock band, and the songs didn't have a lot of improvisation. And the improvisation that would happen would just be collective improvisation where there would rarely be anybody stepping out and soloing, and if it would happen, it would be very limited.

That was actually something that Shane and I really got from Ron Miles. On albums like My Cruel Heart and Woman's Day, which were albums we listened to all the time, they kind of had that thing. There's a lot of writing going on and a lot of patience building of music. We've gone through phases where the music is really palatable, melodic kind of writing, where we literally play the music, and there are phases where it's hard to really tell what's going on -- a lot more abstract or really heavy grooves happening.

I'd say now we're in a phase where a lot of the music we're playing there is a lot of that really dynamic open-ended kind of playing, where it's just like the band gets pretty bombastic and just doing who knows what. But then I feel like that we have enough through-composed music that's just beautiful and melodic that can just balance all that out, which I really like.

I think everybody in the band likes having an audience relate to us. So that's important for us. Something like, "Okay, this is something I can sink my teeth into and this groove can happen the whole time, and we don't have to worry about it flipping out or doing something weird."

I know you and Shane grew up in Denver, but did you guys know each other here, or did you meet at Eastman College of Music?

We did meet in Denver. I think I was eighteen years old when I met Shane, and he was, too. He was going to college at CU, and I wasn't. I was just playing music in Denver. I first heard him play at Muddy's, which is a café that's no longer there. They used to have jazz there. This guy Joe Lukasik was a great saxophone player; he played bassoon, too, and used to jams at Muddy's.

I went down there with a trumpet player named Derek Banach, who's still out in Denver, and a great trumpet player. I went down there, and I heard this great trumpet player ripping. I was down in the bookstore downstairs, and there was this guy saying, "Oh man, who is this guy?" I went and I saw him, and there was this blonde-haired kid wearing a baseball cap.

I used to play at this bar called the West End Tavern on Thursdays up in Boulder. It was a hip-hop night where there would be DJs and a band, and then we'd play and just freak out every Thursday. And then that next Thursday, I saw Shane there, and we just hit it off and we started a band together.

It was all original music. It was a quintet. It was a band where we just wrote this music and had a lot of freedom. We got to play with a lot of cool bands and open for bands like the Roots, Medeski Martin & Wood, Charlie Hunter Trio. We just hit off as musical friends, and I kind of ended up following him out to Eastman, and that's kind of how that all worked.

And before Kneebody there were a lot of the same members, but you were called the Wendel-Endsley Group.

Yeah. We had this period of indecision. It's such a pain coming up with a band name. Shane was playing for Ani DiFranco for a while, and he had done his solo record, and it was all of us. So there was the Shane Endsley record... We used to play at this bar called the Temple Bar in Santa Monica, and while Shane was out on the road, we had this band that was just called Wendel because the promoter at the club, who was a friend of ours, called Ben to just book a random gig on a Monday night. She was like, "What should we call you?" I said, "I don't know." She was like, "I'll just call it Wendel."

We would meet on Monday nights and play, and it was all four of us without Shane. We got all this music together, and that band was called Wendel. It was just frustrating. Then Shane quit doing the Ani gig, and he joined back up with us, so it was called the Wendel-Endsley Group, and we were all frustrated because that sounded like a law firm. Then it was hard to come up with a band name. That takes a long time to figure out.

So what we ended up doing is coming up with Kneebody because that was the name of a song that was on the Wendel CD. Yeah, there was a song called "Kneebody" because Ben's girlfriend at the time... he'd just written a song, and he said, "What should I call this song," and she said, "I don't know. Call it Kneebody." He goes, "Okay, cool."

We just kind of wanted a name that didn't really... The Wendel-Endsley Group, if we had continued calling ourselves that, we definitely wouldn't be.... I doubt a lot of girls like us now anyway, but I'm pretty sure no girls would even think about us. It's also a name that just screams conservative jazz, the band name, maybe to me.

Also, we just wanted a name that would be something where you don't know to think. I mean, the Who could have been anything. Or Led Zeppelin, that's just a random.... A lot band names -- Radiohead, like it's just silly when you hear it for the first time but then after a while, it's called Kneebody. That's kind of how we came up with name. We just looked through our song titles on that record, and we were like, "Oh, that one's kind of cool." It doesn't really mean anything.

Would you say the name fits the band?

Man, I don't know. Yeah, like in retrospect we probably should have called ourselves like, you know, Slayer. In retrospect we probably should have called ourselves Coldplay. I have no idea. There are times where I'm like, "Why are we called Kneebody?" It's the worst band name in the world. But then are times where you hear people say it, and it's like, yeah... Just like any name, once we start saying it a lot you're just like, "That's what it is."

I still tell people my name. I'll meet people all over the world, and they'll be like, "What's your name?" "My name's Kaveh." They'll be like, "What?" Then you say my name enough, and then it's like, "Oh yeah, that's his name," or whatever. When I was a kid, I always wanted to be called Lance. I just thought that was the sweetest name ever. But I'm glad I never changed my name, you know what I mean?

I think the last time I saw the group play was about two years ago at Dazzle and you weren't playing with them. I think they said your wife had just recently had a child.

Yeah, I think that's probably what was happening.

So Nate was playing drums and bass at the same time.

Which is just hopeless for me. What's the point? What really is the point? That's what that all boils down to. I'm just kind of there to say some funny things between songs and carry amps. That's basically just it. Because, yeah, he's really freakish. He's so talented, but he's also so dedicated. I mean, he's just so talented and has been so serious about music from the age of three years old. He kind of grew up around it and he's just got an amazing mind.

I highly recommend going online on YouTube and checking out a Threebody movie. That was a Cal-Arts clinic I couldn't make, and it was just Nate and Ben and Adam -- so sax and drums and keyboards, but Nate played bass and drums at the same time. It's just freakish. I remember the first time he started doing that. Nate and I used to play with a singer-songwriter, a John Mayer kind of guy. We would be playing with this guy and there would be gigs I couldn't make, and Nate would learn a bass part because he's such a freakishly good bass player.

He would learn the bass parts, and he learned how to play the bass and drums at the same time. And he's also such a great singer, so he could sing background while he was doing that. But then it got hilarious because nobody is looking at the singer-songwriter - the star of the show.

They're just looking at the freak in the background, who can do everything -- as well they should. That's what you should pay to see. That's definitely a hidden asset that we have in this whole band. Everybody plays different instruments, but he's definitely takes the cake, and can play them all at the same time.

Follow @Westword_Music