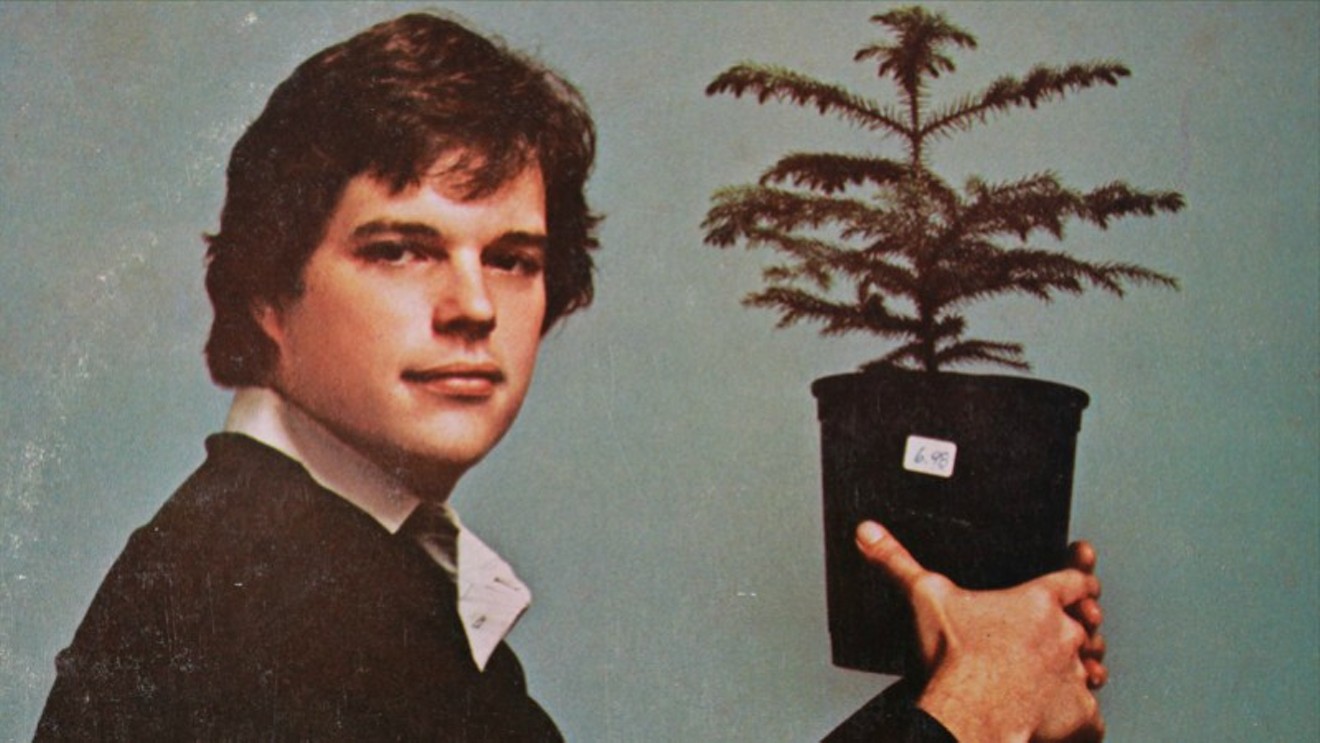

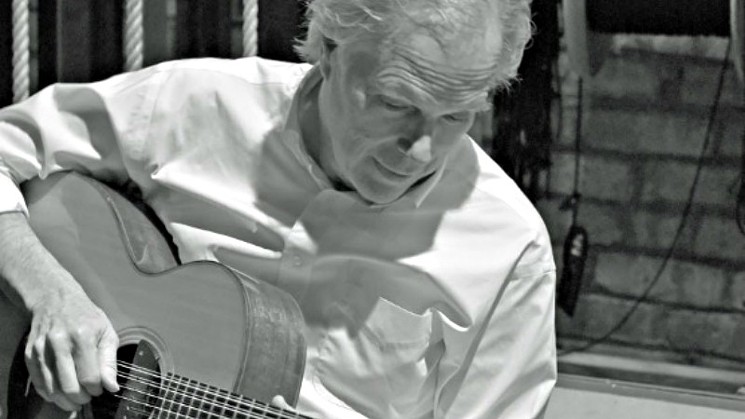

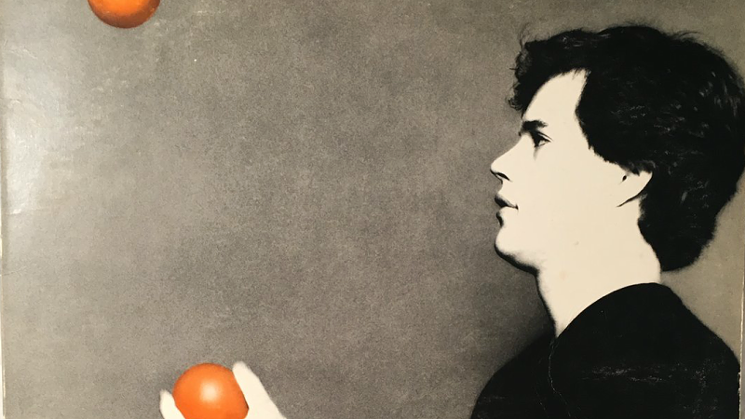

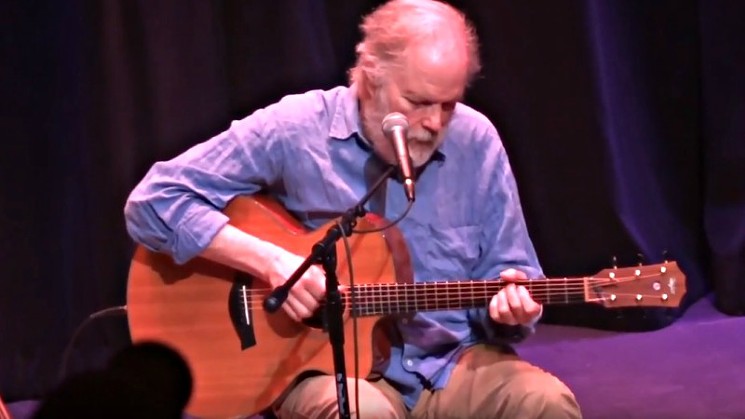

Leo Kottke, who's playing October 19 at the Paramount Theatre with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, is weird in the best possible way. And his career has been, too.

No one's ever accused Kottke of being a pop star. But somehow, he's managed to parlay his awesome aptitude on the acoustic guitar, a knack for instrumental intricacy that's undeniably complex yet somehow warm and inviting, and occasional vocals that amusingly and defiantly stick to the low road into a half-century-long career. His debut long-player, 6- and 12-String Guitar, arrived in 1969, and he released a steady stream of material for decades while quietly influencing generations of pickers, as the dozens of online videos showing amateur players trying to master his licks demonstrate.

Over the years, Kottke, who lives in Minnesota, has become a hero to famous musicians, too, including Phish's Mike Gordon, with whom he's recorded two albums, 2002's Clone and 2005's Sixty Six Steps. But Kottke, who's in his early seventies, remains hilariously unaffected by the esteem in which he's held. He seems satisfied to occupy his own particular reality, which is different enough from the one the rest of us occupy to render his commentary both insightful and delightfully bizarre.

Witness the following interview, in which Kottke pivots from reminiscences of his early visits to Colorado and encounters with Colorado promotion legend Chuck Morris, a devoted fan who served as his manager for a considerable stretch, to how there's little difference between the typical audience and one in a prison (depending on what kind of prison it is), why he doesn't care if ticket-buyers aren't paying attention (except when they don't care), that time he fell off a stage, the importance of not trying, the show he doesn't remember at all that was probably brilliant (though he can't say for sure), the concert he saw that was simultaneously terrible and astonishing, and why making a good YouTube video is probably more important at this point than producing a new recording.

His Wikipedia discography says he hasn't done the latter for thirteen years, which doesn't seem right to him. But who the hell knows? Leo Kottke's world makes sense; the other one is the problem.

Westword: When was the first time you played in Colorado? Chuck Morris says he thinks you're the third person he ever booked to play at Tulagi in Boulder.

Leo Kottke: That was probably it. He told me a band called Greezy Wheels had told him about me. So he booked me. I remember their lead singer sang in her bare feet. I think that's the first time we played in Colorado, but it could have been anywhere. Once I decided not to know where I'm going after tomorrow, I kind of forgot where I was yesterday.

But the show that started Chuck and I on a steady run in Colorado was Tulagi's. And I think it was the first or second one where I dropped an amp on the tuning head on my guitar. So it started out on sort of an awkward footing.

What happened?

I spent a lot of time on the six-string, but I was basically married to the twelve — and I still am, but it's an open marriage now. There was a time where there really weren't any good twelve strings floating around. They were all overbuilt, and the wood itself, the top, was too thick and they all just sounded awful. But that guitar was really anomalous. I got it a couple of months before I played for Chuck. But I destroyed it. I dropped an amp on it.

That guitar had been built in Chicago. I believe he was Serbian, and his name was Bozo Podunavac — what a name. He got mad at me one day, and he yanked out a T-shirt that had three bullet holes in it, and he said, "I'm sending a rocket to your house." He was being sort of funny, but he was pissed off, too. He was a very interesting guy, and it was a beautiful guitar. I recorded on it, and it recorded better than it sounded. I liked that.

I did eventually get it repaired, and many years later, I was looking at it in my house and it fell over, and there went the tuning head again. So it still exists, but the tuning head is still hanging there like a loose tooth.

That was my first job in Colorado, or it might have been the second. This was quite a while ago. To me, everything happens at the same time. I've been that way since I was a kid. But it kind of behooves me to have a more linear reference, and that's as close as I can get to one.

The thing that was memorable about the first job was meeting Chuck. He was, and is, like no one I've ever known. There's only one Chuck. He would book me basically every year after that. In the beginning, I suppose, at Tulagi's, and as he got bigger and bigger, he would take me along and book me in his newer venues and open for bands across the state. So we would end up seeing each other two or three times a year, which is a lot of continuity with touring.

As a result of that relationship with Chuck, you've played in Colorado a lot over the years. Is there something about Colorado audiences that stand out for you?

No, because all audiences are the same. What stands out is the atmosphere that isn't confined just to the audience. It's there in the town or the cities or wherever you are. And that you do notice — some qualifier in the air. And in Colorado, it is a function, I think — and this is coming from a guy like me, who complains about it — of the fact that they don't have any air there.

There's a difference. Things sound different the thinner the air is. And, of course, Boulder is full of schools and colleges and ups and downs topographically. Those things make a difference.

I very rarely play in Minot, but I remember coming on stage one time and saying I was a big fan of a 360-degree horizon. And the room roared. They agreed, which is fortunate, since they live there. So there's that part of it. If the people in the hall are more or less native to the area, there's a color to it. It's kind of brighter in Colorado, because there's less air. So things are easier to see.

I'm making that up. But what's very interesting about audiences is that they are all the same, but there are cultural qualifiers. The big one is an institutional qualifier. If you play in a prison, that is not like every other crowd. But if you play in a federal prison, that is like every other crowd.

An ex-convict had to explain it to me. He warned me when a friend of mine told him I was going to play in a state prison. He said, "Don't play there. There are people there who deserve to be in prison." He had just come out of a federal prison in Atlanta, I believe, at the time he told me. He was laying on the couch with a broken arm; I don't think he'd seen anybody about it yet. But I said, "What's the difference?" And he said, "State prisons, that's where they put the baby rapers and the child killers. That's where they put the people who deserve to be in prison." Because the worst crimes are adjudicated under state law.

Of course, there's some nasty shit under federal law. But a lot of it is white collar or immigration. Maybe kidnapping would be a bad one. It is a different crowd. But federal prisons are pretty much like an open promotion anywhere else.

I used to play in Yugoslavia, when Yugoslavia still existed. The first year I was there, I think this is right, I played in Pula and Ljubljana and I can't remember where else, but in a big sports-arena-type place. And that crowd felt exactly like a state prison. I suspect it's because they were living in a prison-like environment. I had a lot of friends there that would explain how things were. In a totalitarian setup, everyone is a criminal. You have to be just to get along. And everybody knows it. So they have that same oppressed thing, I would imagine, at least when it comes to a concert. What it means is, they aren't a crowd. It's a lot of people in a room, is what it is. In concerts other than prisons, you have a lot of people who will be in concert together. The guys in prison don't really want to be together. Or in Yugoslavia.

So Colorado doesn't feel like that. It feels like most crowds, but with less air.

With your music, I would think it would be especially important to have an audience that's attentive — a listening audience.....

Nah.

Not true?

No. More power to them, but that's up to the crowd. Whatever they're doing is fine. If you want people to listen, give them something they want to listen to. But it can only be something that you, the performer, want to hear. If you're up there trying to make an audience happy, you're in the wrong place. It doesn't work that way.

I really don't care if they aren't listening. Usually they are. It's not an issue.

So if you hear an audience starting to get restless or make noise, you don't change what you're doing? They're going to have to adapt to you?

Well, nothing would change. I'll just keep making myself happy. And it's okay. What is not okay, and I've only experienced this twice, is indifference. It's really apparent when that happens.

There can be plenty of noise. It depends frequently on the room, or the venue, I would say, or the time of day. You never want to play at noon. Noon is, without question, the most ghastly time to perform. And outdoors — outdoors is almost as bad as noon. If you have to play outdoors, it's a lot better to play at night.

That's the same thing as playing to an audience that would rather be doing other things. They're having a good time out there with the bugs and the patchouli oil. It's different. There's no reflection for the sound. What was the question?

You said indifference was worse than inattentiveness. Do you remember the two shows where that happened?

Oh, yeah. One was in Ottawa, and I was a support act. I was opening for Lyle Lovett, and it is the strangest thing. Because indifference is usually very, very quiet. And the other one was in Düsseldorf — and Germany is probably my favorite country to play in. I just love playing in Germany. I love the Germans, I love the country, and like most of us, I'm crazy about the music, going way back. But the first time in Düsseldorf, it was total indifference. It's like playing for an eel. Try and feel something when you're playing for an eel.

What the indifference does is it turns your set into a chore. You've got to just grind it out, and it takes the life out of things. So I ground it out, and the lighting was bad – it wasn't a purpose-built venue, it was a concrete stage with concrete steps. And I headed to the steps off the stage, which didn't have a proscenium arch, and I fell off the stage. Then they were no longer indifferent. They exploded. They laughed their asses off, because I fell down step by step. It must have had a Laurel and Hardy shine to it. So they loved that. But unfortunately, that's where it ended.

That would be a tough way to endear yourself to an audience — falling down a flight of stairs every show.

Yeah. That might be how Iggy Pop got his start. He was always beating himself in the face with a microphone or whatever.

How has your set evolved over the years — and how is it different now than it was earlier in your career?

It's more fun. I don't think it's really changed. All the fundamentals are the same. One guy and two guitars. But I've had time to learn how it all works. In the beginning, you're always kind of mystified. It seems as if there's something going on and you've got to be sure to take part in that. The big thing is, you can't try.

In the very beginning, nerves will make you try. But then, after a while, you'll find out that something isn't working for you. Arthur Rubinstein called this thing the "secret current." It's a terrible name for it, but it does exist. And you begin to notice that it does exist, this in-concert thing. At that point, you're trying, and you're screwing things up, and you don't know it. And then you find out that you're taking things too seriously and you're trying too hard. So that stops, and when it does, everything opens up for you. And for me, that happened at the Kennedy Center one year when I was playing there. I actually recorded the set, because I wasn't happy on stage. I hate listening to myself, but I listened to that because I wanted to figure out what had gone wrong. And you could hear this guy trying. You could feel it. It was a pressure wave coming out of the boombox. Pure horseshit. So I gave that up.

I guess what I've learned is not to try, and you go wherever the set goes. I don't have a set list. And if you just follow the current that Rubinstein talked about, and you miss it, you can get kind of curve-blind. You cannot fight it. You must not fight it. You take it for what it is and you enjoy it. I've learned that, and it makes every night just fine.

It's a really fascinating thing to me, the subject of performance. I got a call from the chancellor from a university in Wisconsin, and they wanted to give me a doctorate. And I told them, "I'm sitting here reading Tales From the Crypt" – a comic book that was banned in the ’50s. It was a doctorate in music performance. And I used to think that was a little silly, until I had a doctorate in it. But there's a distinct thing about performance that's very different from music theory. Theory represents the tools, but performance is the reality of it, and it's a fascinating thing. There's something that happens in the human race when somebody sits down with something that makes noise, and people will come to hear it — and they will prefer one noisemaker over another.

What is that, and how does that work? It's really fascinating. I love to hear talk about it, but very few people do.

I'll give you a great quote. It's not mine. I think I read about it in an interview in the Times with Emma Thompson, who was promoting a movie she'd done with Richard Dreyfuss, I think. And she said, "I think artists are fundamentally inconsolable. It's why they keep doing it."

That speaks volumes.

Yeah. It really does. I definitely think that's part of it. I was just listening to Kelly Joe Phelps, who I really enjoy. I first heard him when he was opening for me in Portland. And he's not performing right now. He has other things he wants to do. We had some email back and forth, and he knows that to keep doing it, there's a motor there somehow — something that makes it happen. And he's looking at that for himself right now, and he thinks I'm doing it. And I have a feeling that might be it. I have a feeling for inconsolability. I have something I got from my first E chord that I can't get from anywhere else, and I really need it. I really need it. And he can see that in other players, I think.

There are players who are exceptionally skilled, and then there are players who might be sloppy and falling all over themselves, but there's something else there. And I think those are the ones that are the most fun and the most interesting. I think they have to do it. I could go on and on about this, and maybe I will at some point — put it on paper. I don't mean to drown you in speculation. But to me, it's just amazing.

I saw a performance by Miriam Makeba while I was still attempting college, here in this state, actually, up in St. Cloud. And it was a disaster. There was nothing about this concert that even marginally worked. Her lighting — and I'm not making this up — was a bunch of work lights and one bare Tungsten lightbulb hanging over her head from a chord that had green, ’50s kind of covering that would slowly weave around while she was singing. And the sound was abominable. I can't exaggerate: What could be wrong was wrong. Feedback, distortion — it was constant. Wolf tones, overtones, too loud, too soft. It was terrible. But it was one of the two or three best performances I've ever seen.

It was riveting, because it was her. She got right in it, and there it was. You couldn't hear her very well. She looked ridiculous standing under a lightbulb. And it was magnificent. How amazing is that?

It must have been inspirational for a performer like you, who doesn't rely on flash-pots and pyrotechnics.

Yeah. I wish I could find where he said this, but Dickens said he wrote to recapture the wonder of his childhood. And when you see someone like Miriam up there doing that, you get it back. You get that wonder. You know she's in it. She has to be. It has to be genuine. It can't be acted or performed in a way most of us think of performance. Oh, yeah, It's inspirational in that way. You're just grateful. There's a lot of gratitude in performance.

How often when you're playing do you lose track of time — when you're not really conscious about where you're at or how long you've been doing it?

Frequently. Frequently. Once, I was playing in Kalamazoo. I was supposed to be playing in Kalamazoo, and I did the sound check. Sound checks are usually done around five and the shows are often at eight, or nine-thirty. And suddenly, I was down in the basement where the dressing rooms were, washing my hands in the janitor's sink, and I kind of came to. And that's something I don't do after a show — wash my hands. I literally came to. I thought, "Where am I?" And I could hear the crowd upstairs, howling. They were nuts. And I remember that I'd gone on. That I'd just played. And I could remember standing in the wings, and that's it. I had no idea what I'd just done. I never had an idea about it. And I figured that meant it was good. If the crowd was an indicator, it certainly was.

That was great. When you go on, you have to have an empty head. Otherwise, you're just going to stumble all over yourself. The emptier your head remains, the better the set is. If you need an indicator of how things are going, that's it. If you don't think about anything, there's no distance between that and the action. So most nights, I'll get a good degree of that. And within tunes, I'll kind of come to.

That's a little troubling. You're still playing a tune, and you're not certain you've covered what you're supposed to have covered up to that point. Most of what I do is written, it's composed. But that doesn't matter, either. So, yeah, I lose track of time. I need to hide a watch somewhere. I tend to go on too long, and I hate acts that go on too long.

Your mention of the importance of not thinking calls to mind one of my favorite Captain Beefheart lines [from the song "Ashtray Heart"]: "Somebody's had too much to think."

[Laughs.] That is a great line. I only saw him live once, but I love his records. Well, most of them.

Speaking of records, it's been a while since you've made one. Is that something of interest to you still? Or is performance more satisfying?

Performance has always been at the center of it for me, and it is more satisfying. But when you get off a good one in the studio and somebody manages to have recorded it — you're all there to do that, but it doesn't always happen — that's equally as good.

The experience of making a record is kind of dreadful. It's a room designed for something other than playing. It's a room made for recording. And if you try to get around it by making a live record, you don't play that night the way you ordinarily would play, because you're aware of the red light.

I left my label. It had so many names attached to it: RCA, BMG, Sony, I think. I owed them two records, but as we all know, everything was up in the air and they didn't know what was going on. Nobody knew what was going on. So I asked if I could bow out.

I do need to make one, though. I've been doing a lot of stuff with Mike Gordon, and we'd love to make a third record together. I also play a lot with a violinist named Dave Balakrishnan [of the Turtle Island String Quartet], and we really hit it off. But I can't make up my mind what to do next, and since I don't have an imposed deadline from a record label, I'm not being forced to record anything. And I'm really enjoying it. But it's getting kind of stupid. I think it's been eight years since the last record.

According to your discography, the second one with Mike Gordon was 2005.

Wow! I think I made one after that — I think. But it's been more than eight years. I make records to support a tour, but most people tour to support the record — although I think that's changed now. I think everybody is touring to make money, because records aren't it anymore.

Does that mean it's less important to make records today, and more important to connect with people face to face?

Yeah, I think so. Especially for the acts. A lot of people don't like being on the road, but they're doing more of it because of what's happened with the recording industry. There's been a huge effect from YouTube, and I don't think anybody's figured it out yet. If they had, there'd be a lot of middlemen there. I know what I would like to do is just put up a couple of things where I'm sitting there playing something.

I listen to a lot of people on YouTube. There are two Bill Evans performances no one would ever have heard again — one in an apartment with Marty Morell on drums and Eddie Gomez on upright in Helsinki. You can see through the window. There's probably six or seven people, including a little girl who keeps playing with Marty's drum keys. That performance is astonishing — great piano — and thanks to YouTube, it's possible to hear it again.

Just like we were saying about Dickens and Miriam Makeba, I've got a lot out of YouTube — including a lot of irritation. If you put an iPhone up in a room, the sound is going to be pretty putrid unless originally it was very, very loud in the room. That tends to help the sound survive the compression. But even the worst shit that shows up, including me — they tend to get nights I'd rather not have preserved — even that will sell tickets. It used to be if you had an LP out, it made you real. And I think that's what happens with YouTube. If you're all over YouTube, it makes people real.

I don't know. But I want to put up a couple of things where I can play something, and it'll be an example of more how it sounds. Then you can get in closer and actually see the playing. It interests me. I don't know how to do it. But Chuck Morris has handed me over to his nephew — I've got a new Morris — and they know all about that shit. They're going to tell me how to do it, so I'll probably do something like that.

Leo Kottke with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, 7:30 p.m. October 19, Paramount Theatre, 1621 Glenarm Place.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]