Deaton is best known in Denver for his Sculptured House — aka the "Flying Saucer House" and the Sleeper house because of its appearance in a Woody Allen sci-fi comedy — located on a mesa in the foothills. But there's much more to Deaton's vision and work than those cutesy labels imply, as Westword explored in a 1991 profile of the architect a few years before his death. That article predates our online archive, but here are some observations and Deaton's own remarks from the interview that help shed light on what the current celebration is all about.

1. It's not about spaceships.

"No, I wasn't trying to be streamlined or futuristic," Deaton said, explaining the evolution of the Sculptured House in Genesee. "I was going to do a piece of sculpture for its own sake. It became long and low and flat because of the internal planning, and also to be part of the mesa. I like to think that it grew here, like a very friendly, cooperative mushroom."

2. But it is about natural forms.

Born in Clayton, New Mexico, the son of an oil geologist, Deaton grew up in Depression-era Oklahoma and Illinois. His formal schooling ended with high school, but he had a strong sense of form, influenced by geology trips with his father. He was fascinated with roundness: the curved spaces of the caverns at Carlsbad, the water-smoothed boulders in the Kiamichi Mountains, the circularity of certain plant forms. "Anything curvilinear spooks a lot of architects," he noted. "They're just fine as long as they're on the T-square, triangle and compass. But they go to freehand, and then they think they're into free-form, and that's death. That's like trying to design a wad of chewing gum."

3. And science, too.

During World War II, Deaton worked in aircraft engineering and design at a Lockheed defense plant in California, translating aerodynamic forms into sheet metal. "I was dealing in metal sculpture and didn't know it," he said. "I read everything I could, and I realized that, technically, you could accomplish almost any shape you could visualize — and this was before the computer era."

4. If you're going to follow your dreams, it helps to have other resources.

While still in his teens, Deaton created and marketed a drill-for-oil board game called Gusher, a distant cousin to Monopoly. After the war he moved into industrial design, securing dozens of lucrative patents on bank-vault doors, security systems, modular furniture and light-diffusion devices. Money from the patents allowed him to turn to architecture and eventually open his own firm. Only a handful of his pioneering designs ever made it past the proposal stage. The patents "gave the income I needed to say no," Deaton said. "I did fewer buildings after that, but the ones I did, I did the way I wanted to do them."

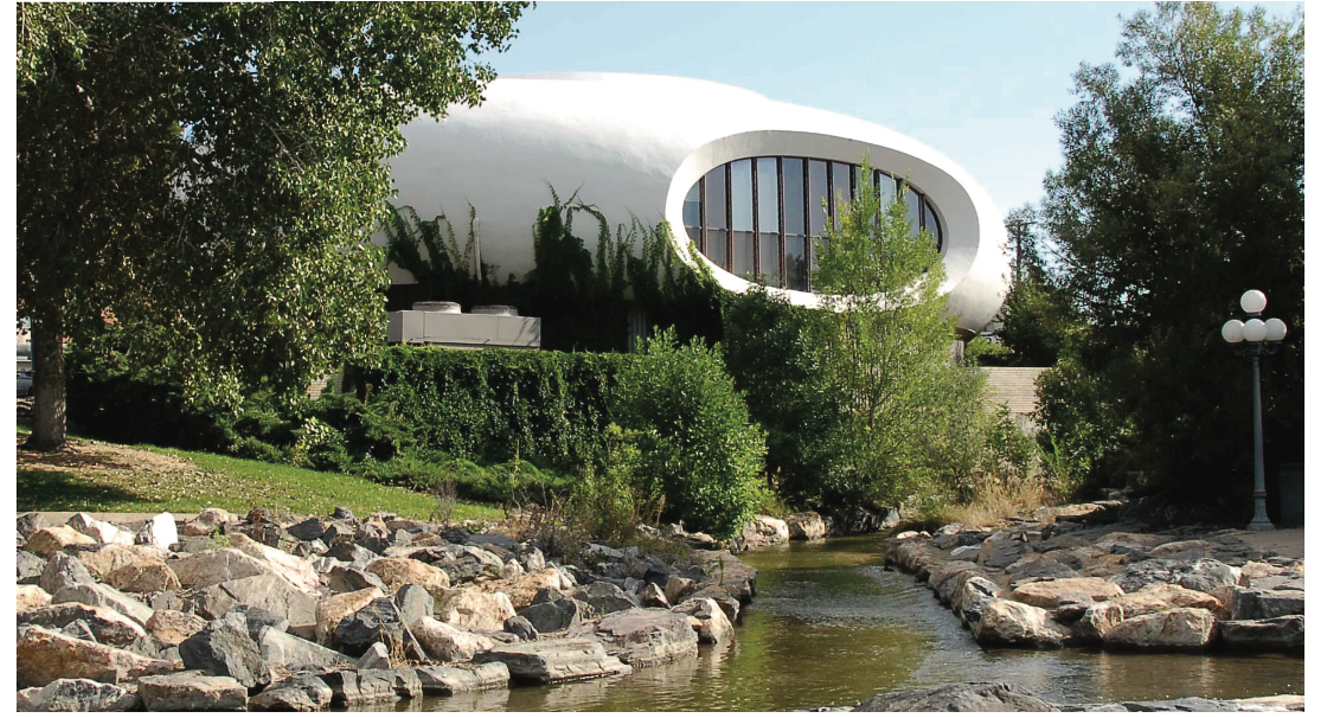

5. The Englewood bank has a big brother in Casper.

One of Deaton's first proposals to make it off the drawing board was the Wyoming National Bank in Casper, completed in 1963. Rejecting traditional bank design as reminiscent of mausoleums, he created a domed lobby supported by petal-shaped concrete ribs, a kind of well-lit lily pad in which the walls bend gently away from you. "I wanted people to be more important than the bank," he explained. Though the structure remains, the interior has undergone great alteration; another early project, the round Central Bank annex in downtown Denver, was demolished in 1990.

Charles Deaton's Sculptured House in Genessee is a familiar landmark for motorists heading west on I-70.

CR Barnett

When Deaton set out to build a mountain home for himself, his wife and their three daughters, the engineers and contractors said it couldn't be done. Not the way Deaton designed it, so that it seemed to float, impossibly cantilevered, off the side of the mountain. But Deaton came up with new methods and materials; the exterior consists of only three inches of concrete, pumped and hand-troweled over a welded steel frame, resting on a hollow pedestal that provides an additional two levels of living space. "I wanted the shape of it to sing an unencumbered song," he wrote in an article published in 1966. "In building this house, I believe I have committed an act of freedom. I am out of the box, off the streeted grid."

7. Deaton never lived in his dream house...

Although rumors thrived in Denver in the 1960s that the Sculptured House had been purchased by Hugh Hefner, who'd furnished it with round beds, it remained a vacant shell for decades, the interior unfinished, until after Deaton's death. Deaton stopped working on the project for personal reasons. "I always thought I'd come back to it, but the family situation changed," he said in 1991.

8. ...which got famous for all the wrong reasons.

Woody Allen's use of exterior shots of the Sculptured House in his 1973 film Sleeper, as well as a bit about an "orgasmatron" inspired by the house's rotating elevator chamber, solidified the house's association with "futuristic" design, an association Deaton always rejected. Still, he managed to bond with the reclusive director in long, tight-lipped games of poker. "He doesn't say anything," Deaton later recalled. "He just takes your money."

9. Sports stadium design owes a bunch to Deaton.

In 1967, Deaton received a commission for Arrowhead Stadium and Royals Park in Kansas City's Harry S. Truman Sports Complex. Among other innovations, Deaton's design called for a retractable roof that could be parked between the stadiums as part of an independent exhibition hall. There was a legal battle over credit for the finished design that went on for years, as Michael Paglia later detailed. Although other stadium designs by Deaton never led to fruition, his emphasis on better access, wider concourses, improved sightlines and other people-oriented features helped paved the way for a new era in sports arenas.

10. The fun still shows.

In the late 1990s, the Sculptured House was rescued from limbo by new owner John Huggins, who invested millions in completing the interior (designed by Deaton's daughter, Charlee Deaton) and finishing an addition devised by architect Nicholas Antonopolous, Charlee's husband, who'd worked on the design with Deaton in his last years. The event was widely celebrated in design magazines, part of an emerging re-discovery of the man and his work that continues with the current Englewood hoopla and renewed interest in the Casper bank and other works. "Time goes by, and the people who use the buidling all change, and you come back to it in a hundred years, and the fun still shows," Deaton said. "It's still there."