When he was growing up in the '60s, Steve Patterson lived in Stratmoor Hills, just ten minutes south of Colorado Springs. In the late '80s, he moved to the nearby town Security.

Now 62, Patterson says he's lived a happy life, albeit one with numerous health complications. And he's lost more than a few family members to cancer, something that he had always assumed was just bad luck.

But about five months ago, his cousin, Mark Favors, told him that both Stratmoor Hills and Security had been supplied with contaminated water for decades. The water had dangerously high levels of what's known as PFAS, a family of chemicals linked to devastating health ailments and cancers. A C8 Science Panel study, finished in 2013, showed that exposure to PFAS was linked to six diseases: ulcerative colitis, pregnancy-induced hypertension, thyroid disease, testicular cancer and kidney cancer.

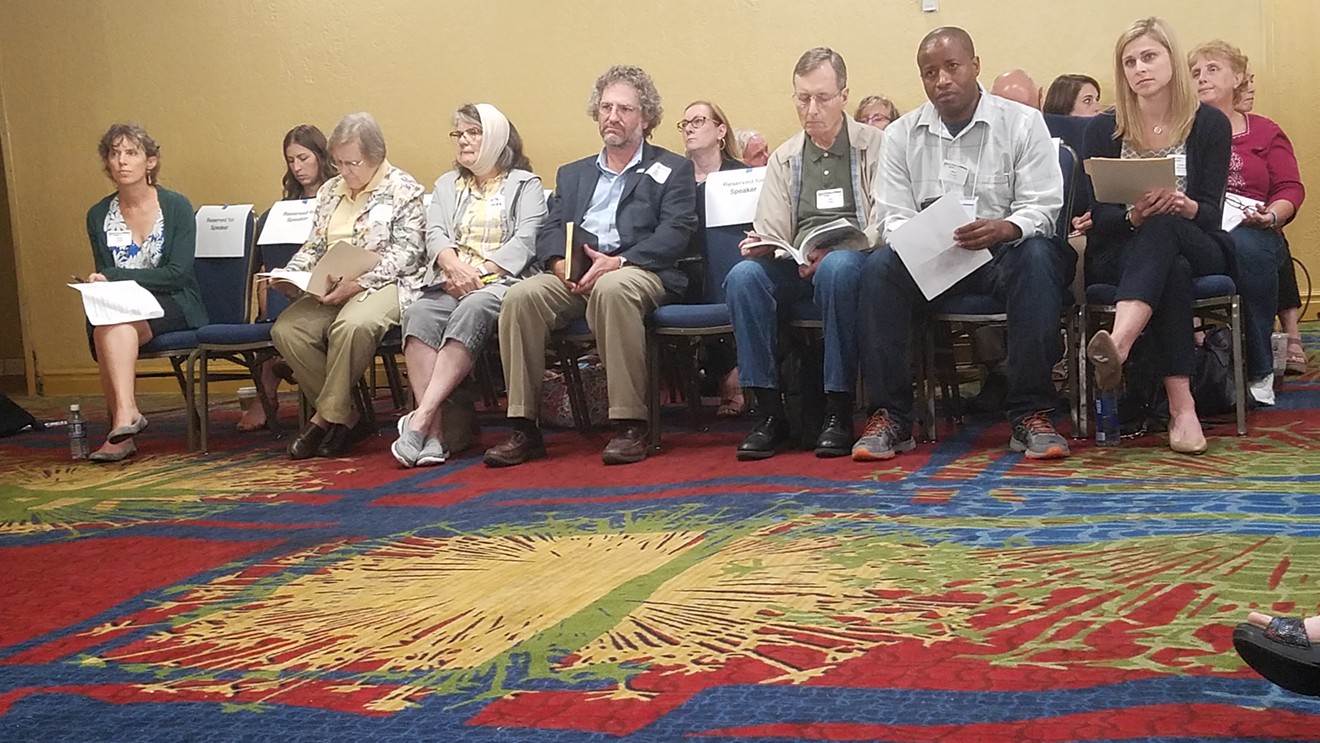

Armed with this new knowledge, Patterson and other citizens who consumed the contaminated water of El Paso County are fighting back. Some have joined a class action lawsuit against companies like 3M that produced the chemicals. Others are trying to pressure the state and the Environmental Protection Agency to lower maximum contaminant limit for PFAS in water. On August 7 and 8, water-district employees and community advocates spoke about the water contamination for almost ten hours at EPA listening sessions organized in Colorado Springs.

PFAS contamination in El Paso County likely came from firefighting foam used by Peterson Air Force Base, according to an Air Force study published in July 2017, and residents have been unknowingly ingesting water with high levels of PFAS since the ’70s.

A groundbreaking series of articles by Sharon Lerner for The Intercept showed that large corporations like DuPont and 3M and the Air Force and Army have known for decades that exposure to PFAS was linked to serious health issues. The Army Corp of Engineers even told Fort Carson Air Force Base to stop using PFAS products in 1991, according to reporting by the Colorado Springs Gazette. But that didn't stop Peterson Air Force Base from continuing to dump diluted firefighting foam into the ground.

According to the Air Force study, the use and disposal of that PFAS-saturated foam led to contamination of drinking water sources downstream from the base, most notably the Widefield Aquifer, which serves at least 70,000 people. Citizens became aware of the problem in May 2016, when the EPA dropped the health advisory limit for PFAS from 400 to 70 parts per trillion. Local water districts quickly realized that some of their groundwater exceeded this new health advisory limit. Since then, water district officials have implemented water filtration systems to remove the pollutants, while also buying water from other areas. But those fixes are only temporary, according to Kirk Medina, director of the Stratmoor Hills water district.

All of Patterson's relatives who died from cancer and other sicknesses lived in areas with PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Patterson gave his sister a kidney in 2003 because both of hers stopped working. After she died of kidney, liver and spine cancer in 2013, doctors told Patterson that the kidney that he gave her may have been cancerous. Both Patterson and his brother Jerry were diagnosed with prostate cancer in back-to-back months in the winter of 2013-’14, and their father died of colon and prostate cancer at age 64. A year ago, Patterson's grandson had to have his kidney replaced; he was just fourteen.

Now Patterson lives in constant fear, not knowing if his remaining kidney is going to give out. He wonders if he will be the next to go. "What is my future going to look like?" he asks. "Am I going to live as long as my dad, or am I going to live longer?"

For residents of the affected areas, the EPA and state officials have not responded quickly enough to their concerns; despite learning of the contamination in spring 2016, the listening sessions in early August were the first occurrences of the EPA visiting with the community.

State officials have also been dismissive of their concerns. In a June 2016 study about the water contamination in El Paso County, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment researchers concluded that there was "inadequate information available on risk factors for individual cases and drinking water exposures to make definitive causal associations between drinking water exposures and increases in kidney and bladder cancer." Instead, the report pointed to obesity and smoking as possible factors leading to the higher cancer rates.

Liz Rosenbaum, founder of the Fountain Valley Clean Water Coalition, read the state's report and says she was left with one thought: "Our voices are not being heard."

After the EPA listening session, residents are hopeful that some action will finally be taken. Rosenbaum and other residents are pushing for the EPA's recommended maximum contaminant level of PFAS to be dropped from 70 parts per trillion down to 1 part per trillion. The Fountain Valley Clean Water Coalition also wants bio-medical monitoring that tracks whether someone is getting sick because of PFAS exposure for those who live in the affected areas.

"Families need to know if they have hereditary disease in their family or if it is an environmental contamination," Rosenbaum says.

Others in the area are hoping to be reimbursed for all the medical costs they've incurred to treat possible PFAS-related complications. Patterson's ex-wife and two of his children have joined the class action lawsuit against 3M and other manufacturers of the firefighting foam.

And representatives of the Fountain Valley Clean Water Coalition want to participate in any negotiations between local officials and companies or the government. A recent trip to the Pentagon by local water-district officials and the Fountain mayor to discuss the contamination with Air Force officials did not include non-elected representatives from any of the affected communities.

After listening for many hours on August 7, Doug Benevento, EPA administrator for the Mountains and Plains region, told the crowd, "What I've heard is that you want us to work harder and faster. You want to be included. And you want more outreach and meetings like this." After the listening sessions, the EPA announced it would assign an agency liaison to the community.

Carla Lucas, who fractured her skull in a hailstorm the day before the listening sessions began, made it a point to still attend. "I feel that the most important thing is to have our aquifer cleaned up," she said. "When will we start taking human health above corporate profits?"

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]