“Do you guys have a warrant?” Keller asked the three ICE agents — two men and one woman — as they escorted García to an unmarked gray SUV parked in front of the Lindsey Flanigan Courthouse in Denver.

“Yes, sir,” answered one agent wearing a black jacket over a flannel shirt.

“Can I see it?” Keller asked.

“No, sir,” responded the agent.

“Can you guys tell me who called you?” Keller pressed.

The agents ignored him.

García did not struggle or yell as he was being handcuffed. Instead, he solemnly asked the agents in Spanish whether he could call his wife to let her know where he was being taken.

Keller was stunned that his client was being apprehended. García had no prior removal orders and had gone to the courthouse that morning to tend to a misdemeanor DUI charge. García knew he had a drinking problem and was trying to get it under control.

But since President Donald Trump issued an executive order on January 25 that effectively prioritizes all undocumented immigrants for deportation — unlike the Obama-era policy of focusing on convicted felons, recent border-crossers and gang members — immigration-related arrests in the United States have gone up considerably. The Los Angeles Times found that 8 million people in the United States are now under threat of deportation, compared to 1.4 million in 2016, and ICE arrests were up 38 percent during the 100 days after Trump’s executive order, compared to the same period last year.

What Keller didn’t know when García was apprehended was that the ICE agents involved may have been breaking Immigration and Customs Enforcement policy with regard to making courthouse arrests. Nor did Keller know just how often courthouse arrests like the one he was witnessing are happening in Denver and surrounding jurisdictions including Adams, Jefferson and Arapahoe counties.

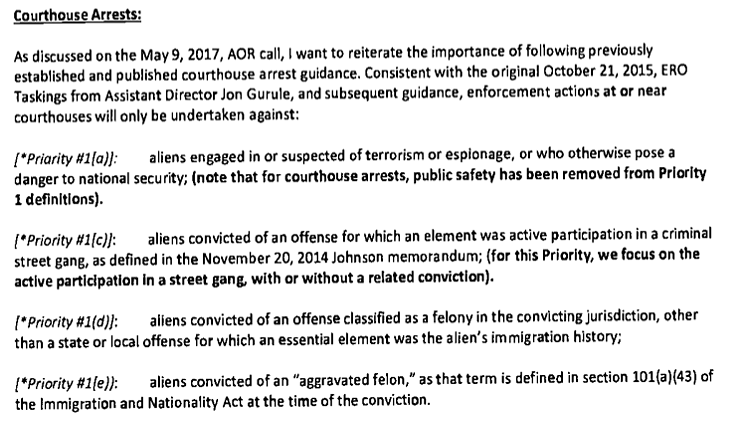

Westword recently obtained 29 pages of internal ICE documents through a Freedom of Information Act request. The documents (published in full at the bottom of this article) show that ICE still makes its agents review and sign a protocol concerning courthouse arrests, even though Trump’s executive order effectively loosened rules agency-wide. The FOIA documents include a memo sent by the acting director at ICE’s Denver field office, Jeffrey Lynch, detailing how courthouse arrests should focus on four categories of undocumented persons: “aliens engaged in or suspected of terrorism or espionage,” “aliens convicted of an offense for which an element was active participation in a criminal street gang,” “aliens convicted of an offense classified as a felony in the convicting jurisdiction” and “aliens convicted of an ‘aggravated felony,’ as that term is defined in [immigration law].” Lynch’s directive, sent to his top-level officers on May 12 (seven days after Garcia’s arrest), is based on guidelines from a November 2014 memo issued by former Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson.

According to Hans Meyer, principal of the Meyer Law Firm, García did not fit into any of the courthouse removal categories, since his DUI was a misdemeanor. In most cases — including García’s — Meyer says DUI charges do not meet the definition of an “aggravated felony” under immigration law. (Aggravated felonies often dovetail with felonies under state law and include things like murder, rape, drug trafficking, kidnapping and money laundering.)

“In the sense of ICE’s hunting license at courthouses, this shows that they’re poaching under their own rules,” Meyer says.

García is not alone in having been arrested at a Colorado courthouse with no felonies or aggravated felonies on his record.

Included in the FOIA documents is a spreadsheet that shows ICE arrests in Colorado from October 5, 2016, through May 9, 2017. It details 133 arrests carried out by ICE agents in Colorado: 52 at courthouses (31 in Denver), 44 at probation offices (twelve in Denver), two at Denver pre-trial services, and seven at “RMOMS,” which stands for Rocky Mountain Offender Management Systems. RMOMS is a private company that contracts with municipal and state governments to supervise parolees, people on probation and individuals assigned to drug-treatment programs.

According to the ICE spreadsheet, some individuals arrested at courthouses had felony convictions on their records, but others had only misdemeanors, including minor charges like possession of a controlled substance and bicycling under the influence.

It’s not clear whether the information represents all ICE arrests that occurred in Colorado between October and May; when Westword asked the agency for more information about the arrest database, we were referred back to its FOIA office, which had taken a leisurely five and a half months to respond to our initial request.

Meyer suspects that the data represents only a fraction of all ICE arrests in Colorado that occurred over those seven months. “My suspicion is that it’s not even close,” he says after reviewing the FOIA documents. “We’ve probably represented thirty people in detention in those seven months, and we’re just one law firm.”

The spreadsheet also doesn’t show any arrests at jails, even though ICE is known to request inmate release dates from sheriff’s departments.

“What [the data] did confirm, though, is what we’ve heard in the community: Courthouses and probation departments are where folks are getting picked up, and the places that have the most activity in Denver,” Meyer adds. “It also appears that ICE is far more enmeshed in the rehabilitative process than we suspected. They’re not just showing up at courts and probation departments; they’re showing up at pre-trial services and the outsourced, private sub-contractors that people are assigned to when on probation.”

Meyer says that having ICE piggyback on the various levels of the criminal-justice system undermines efforts by prosecutors and judges who have agreed to work out probation or pre-trial deals with nonviolent, often first-time, undocumented offenders.

It also appears that Denver does not keep hard data on the numbers of courthouse arrests by ICE. Answering on behalf of the Mayor's Office and the City Attorney's Office, Hancock's Deputy Communications Director Jenna Espinoza said that the city was not aware that 31 individuals had been arrested over seven months and had only compiled anecdotal evidence about how often courthouse arrests by ICE occur.

As recently as February, officials in the Denver City Attorney’s Office were either unaware or tight-lipped about ICE making courthouse arrests. At a Colorado Latino Forum on February 2, Deputy City Attorney Cristal DeHerrera even told a room of concerned residents at North High School that it was completely safe to attend courthouse appointments.

But the tone of city officials quickly changed when the Meyer Law Firm published a video that captured undercover ICE agents stalking the hallways of the Lindsey Flanigan Courthouse on February 16. After the video was released, city prosecutors had to drop nine domestic-violence cases after witnesses, presumably undocumented, said they were afraid to show up to court.

Then, in April, Mayor Michael Hancock and members of Denver City Council sent a letter to ICE requesting that it respect “sensitive locations” like schools and courthouses. The agency responded to Denver’s top officials with the same frank message that former DHS secretary John Kelly and Attorney General Jeff Sessions had given California’s chief justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye on March 29: ICE will continue to make courthouse arrests.

Months of political wrangling ensued as immigrant-rights advocates in Denver pressured city officials to pass a policy that would limit Denver’s cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. On August 31, Mayor Hancock signed the Public Safety Enforcement Priorities Act into law, which does not prohibit ICE agents from conducting arrests in courthouses, but does bar city employees from communicating with the agency unless presented with a signed warrant. ICE’s Lynch called the ordinance “dangerous” and “irresponsible.”

The new law will soon be put to the test: After Westword received the FOIA documents, we sent an open-records request to Denver’s Department of Public Safety, which produced multiple emails between ICE officers and Denver employees who work with pre-trial services. The records show that one “deportation officer” with ICE, Jose H. DelReal, has been communicating with at least three Denver employees to obtain specific times when ICE targets would show up at pre-trial service appointments. “We are requesting an estimated release time in order to take custody of the subject,” DelReal wrote in an October 18 email.

“Could you please provide a more accurate estimate for the release time?” an ICE officer wrote in another email to pre-trial service employees on April 28.

Under the new ordinance, such communication on the part of Denver employees is prohibited. But Meyer says it remains to be seen whether — or how — the city enforces its policy of non-communication with ICE. “The recent passage of the local ordinance to extract ICE from our city is an important step, but we need to write a stronger prescription,” says Meyer. “Training, implementation and accountability from the city and its leadership is critical, especially in light of these records.”

Upon learning of the pre-trial and probation-office arrests, Councilman Paul Lopez, who was one of the immigration bill’s co-sponsors, says, “I was not aware that these arrests were occurring. The Denver Public Safety Enforcement Priorities Act was drafted after hearing from the community about these types of practices.

The act puts an end to all uniformed and non-uniformed city employees communicating with ICE about appointment details or asking for citizenship status when not required by federal or state law. It is not the city’s responsibility to do ICE’s work. It is in the best interest of our city that all folks continue to show up to their probation appointments rather than avoid them out of fear that ICE will be waiting.”

Other emails included in the FOIA documents show various ICE personnel asking for clarification about agency procedures — not just for courthouse arrests, but also for arrests at probation offices.

On May 12, one ICE employee wrote: “First and foremost, I would like to have a specific, written definition of ‘At or Near.’ That’s way too nebulous as it stands.”

In the same email chain, another officer wrote: “Can there be a clarifying statement to this new policy that will protect those officers making a probation arrest in a location where the court and probation are co-located?”

Unlike the detailed memo he provided about courthouse arrests — laying out the four categories of targets and purportedly preventing ICE agents from arresting bystanders or victims of domestic abuse — Lynch responds to the question about probation offices with a terse answer: “If the ICE business is with the probation office, then the officers are clear. We will defend that action if questioned.”

The Meyer Law Office’s Gonzales says the emails are “alarming.” “It’s clear that [ICE’s] own agents are confused.”

Courthouse arrests may come to a head, and not just because of ICE’s inconsistencies following its own protocols. With local officials such as Hancock and powerful legal authorities across the nation, including California’s chief justice, asking for the practice to stop, Gonzales and Meyer believe it’s time for the judiciary to decide on the issue.

Christopher Lasch, who’s with the University of Denver’s Sturm School of Law, has a forthcoming article in the Yale Law Journal Forum in which he discusses how the American court system is built on the understanding that people can tend to business at courthouses without fear of being arrested at them.

Lasch’s piece, which has been released online as a draft, describes how protections from arrest at courthouses were established centuries ago in English common law, and notes that the same common-law doctrine from England was used to form the foundation of the U.S. court system. Only recently, with ICE’s courthouse arrests, has the issue come up again in a serious way, Lasch argues.

Like Gonzales and Meyer, Lasch believes that it will probably be up to the courts to decide if they want to push back on the practice.

Even before he reviewed the FOIA documents, Keller says he was going to challenge García’s arrest. “We were ready to dig in and fight his case,” he says.

But it turns out that the last time Keller saw García was when he got into the ICE SUV. Following five days of silence after the arrest, Keller received a call from the immigrant detention center in Aurora. García had signed papers authorizing his deportation. He’d given up.

[Below is the entire FOIA response from ICE]

ICE FOIA Response to Westword 2017