Boyles first hit the Denver airwaves during the early 1970s, and over the years that followed, he worked as a traffic reporter, disc jockey and talk-radio host. He also bounced from station to station, serving stints at long-gone signals (KAAT, KLAK, KWBZ and KYBG) and some that survived, including KOA. At the latter, he grew close to Alan Berg, who was murdered by a white nationalist group called The Order in 1984. Boyles spiraled after Berg's death, but two years later, he was able to overcome a raging substance-abuse problem, and he's now been clean for more than three decades.

In 1994, Boyles landed at KHOW, where he held down the morning-drive slot for nineteen years and became known for his obsessive focus on topics such as the JonBenét Ramsey case. In 2013, station management fired him after he got into an argument with producer Greg Hollenback that turned physical; Boyles admits to having grabbed Hollenback by a lanyard around his neck. However, he was promptly hired by KNUS, where he's continued to make friends and enemies in almost equal measure.

Once a liberal, Boyles began a philosophical shift in the late 1980s and subsequently landed at a point that's decidedly right of center. As such, critics have branded him a hater for, among other things, his hard-line positions on immigration, not to mention Barack Obama birther theories that he continues to defend. But as an occasional guest on Boyles's shows, as well as someone who's covered him for Westword during more than a quarter-century, I find him to be too complex a figure to be placed in a single ideological box — and he clearly delights in taking on both political figures with whom he disagrees and media organizations that he sees as unwilling to speak truth to power.

Love him or hate him, Peter Boyles is a Colorado original — albeit one who started out somewhere else. Here's his story, supplemented by more than a dozen links to previous Westword posts.

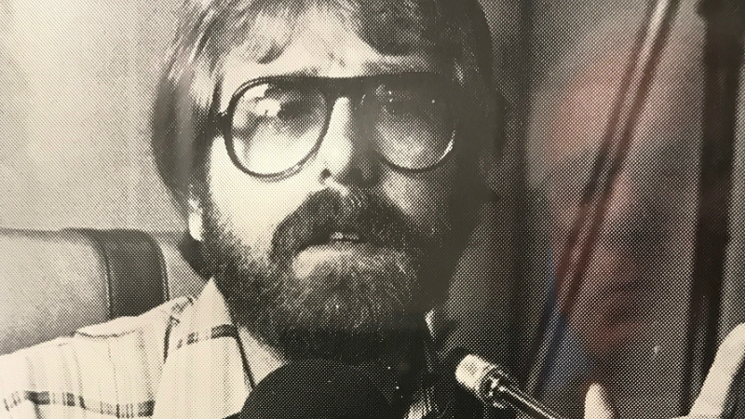

A photo of the younger Peter Boyles on the air — and yes, that's a reflection of Boyles today at the right of the frame.

Courtesy of Peter Boyles

Peter Boyles: I'm a Pittsburgh kid from a union family and worked in the mill as a kid. And when I started to read, I found myself drawn to people like William Jennings Bryan and the so-called Prairie Populists who mistrusted and distrusted the railroads and the big banks and American foreign policy. Without realizing it, I was headed in that direction. And I was heavily influenced by early union organizers. In the coal mines, there were some really remarkable guys. I remember sitting in a bar the first time I could vote; it was Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater [in 1964]. There was an old coal miner at the bar, and I was a wiseass then the way I'm a wiseass now, and we were talking about the election. We were Johnson Democrats, and I remember asking this old guy, "Who are you voting for?" And he said, 'Who's running?" I thought he was a fool, but I said, "Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater." And he looked at me, took a drink and said, "My president's John L. Lewis," the head of the coal miner's union. And I thought it was funny until later, when I realized that John L. Lewis did more for this man and his family than any Republican or Democrat rolled into one. He supplied them with safety, he supplied them with a living wage, he took care of their hospitalization and retirement plans. That was the union. It certainly wasn't Barry Goldwater, and it wasn't going to be Lyndon Johnson. And I've thought about that old man a lot. He was telling me something that was extremely wise. These people aren't really on your side, and I've thought about that quite a bit doing radio shows and doing some writing. These guys really aren't on your side. They just pretend to be for the time being.

Your background doesn't immediately suggest a path to a career in media. How did you end up broadcasting in Colorado?

I met a woman from Colorado Women's College and married and stayed in Denver. Started college at Metro, worked in a warehouse for a while, and also worked for a guy who was doing lawns and stuff. Then I met a guy I was going to school with who said, "The AAA Auto Club is looking for a writer to write down the traffic reports" — but you had to be at work before six o'clock in the morning. So I went over, met Dan Hopkins, who was one of the great influences of my life; he retired as [former governor] Bill Owens's press secretary. Dan tells the story that I got a haircut on the spot because I was such a longhair. Truly. He said, "Your hair's too long," and I cut my hair right in the Auto Club. And the next day I was working as a writer.

Just by a process of elimination, I figured the job out — and I used to steal the traffic reports. We had CB radios and we had a radio that we had poached out of a wrecked Mercury in a junkyard, Danny and I, and we set the buttons on KIMN radio, on KHOW, and on KOA. I didn't know anything about formatics and things like that, but those stations had guys like Dick Dillon and Don Martin flying airplanes over the city, and they would do traffic reports, and I learned to punch the button in and steal. I would steal what Dick Dillon would say or what Don Martin would say, and I'd write it down as a report and pass it to the on-hour guy, the announcer. I was stealing left and right. And finally, I went to Dan Hopkins and said, "I can be both the traffic writer and the traffic reporter and save you a bunch of money. You can pay me more, and I can get the job done." And the morning my daughter was born was my first morning on the air.

When was that?

I think maybe ’73 — and the first time I ever got on the radio to do a radio show as a disc jockey was probably ’77. I got a job working at KAAT radio, hired because I was a traffic reporter, and the late Jack Merker was looking for a guy to do weekends, and I was his traffic reporter. And I needed money very badly. My daughter had been born and my dad had passed away. It was pretty tough economic times. And I went down to KAAT radio, and I sat in the studio with him and I watched him for one day, and the next day he said, "Take the microphone," and he walked out of the studio. I think I threw up I was so frightened, and I probably did the worst half-hour in Denver radio history. But when he came back in the room, he said, "It wasn't that bad." And in true radio fashion, we went to the Playboy Club for a drink afterward and I realized, hey, these guys don't pay for alcohol. Jack took me in there, and the rest is history. He started me out as a weekend guy and I fell in love with the radio business. Gus Mircos was working at KAAT, and Eddie Greene, who's leaving Channel 4. Ed was a disc jockey. And Ed and Gus and Jack taught me how to do disc-jockey radio.

Out of Jack hiring me as a disc jockey, I got to do travel-and-recreation reports on KOA radio. I was working seven days a week while I was going to school, and I came across the late, legendary Bob Lee. We started doing this banter on the Saturday morning shows, and people liked what we were doing. And Bob Prangley — he's gone now, too — had been the sales manager at KOA radio, and he had left to go to become the general manager of KLAK radio, which was a country music station. Bob Lee went there, too, and they hired me to join Bob. And that was the first hit show.

When did you start doing talk radio?

I'm an alcoholic and I'm an addict, and my disease was raging, and Bob and I had some issues about how things were being done. And I knew Mike Wolfe — there's a name from the past — and Mike had been hired by John Mullins to take over KWBZ radio. Mike called me up and said, "You're smart. Would you like to do talk radio?" And I said, "Yeah," because I didn't know what to do. My son had been born, I was really dissatisfied with being a disc jockey with Bob — nothing to do with anything, but we were both terrible alcoholics. So I went over to KWBZ and did mornings there, and that's when I met everybody, all the talkers who were working there. And that's of course where I met Alan Berg. I was doing mornings and Alan was doing afternoons. Alan had been at KHOW doing nights and had been fired for some shenanigans. But we both worked at KWBZ when it folded. They took everybody off the air.

I call KWBZ the mother of all radio stations in Denver, because Mike Rosen worked there and Gary Tessler worked there, Alan worked there, Woody Paige worked there. All these legendary characters went through that radio station. And from there, I got a job at KHOW doing nights, eight to midnight, working for Hal Moore; Hal and Charley were doing mornings and I was working eight to midnight. And Alan had to go to Detroit and then he was going to go to Oklahoma, and there's the famous story: Alan goes to Oklahoma City and the first caller wanted everybody to know this guy was on in Denver and said Jesus Christ was a black homosexual. That kind of ended Alan in Oklahoma. But then they brought Alan back to KOA. He was working afternoons and then the mornings opened up because Gary Tessler was going to leave KOA and move to KNUS, which was a talk station; it used to be a country music station. And I was brought over to do mornings on KOA from nine to noon and Alan doing afternoons.

A lot of people have written about the assassination of Alan Berg, and that changed the face of Denver radio. I left KOA during that time period; my best friend had been murdered and I was trying to struggle into my own sobriety. I don't blame anybody about any of this stuff but me. What I was doing was my disease. Then I got sober and I went from there to KYBG, worked there with Dave Logan and all the great guys who were there, and then back to KHOW to do mornings there for almost twenty years, after it changed from the music format. I went back to KHOW and did mornings until I reached out and grabbed Greg Hollenback. In spite of what everybody says, I grabbed him by the lanyard, and I got fired for it. And two days later, I had a job working for Brian Taylor at KNUS, which is where I am now.

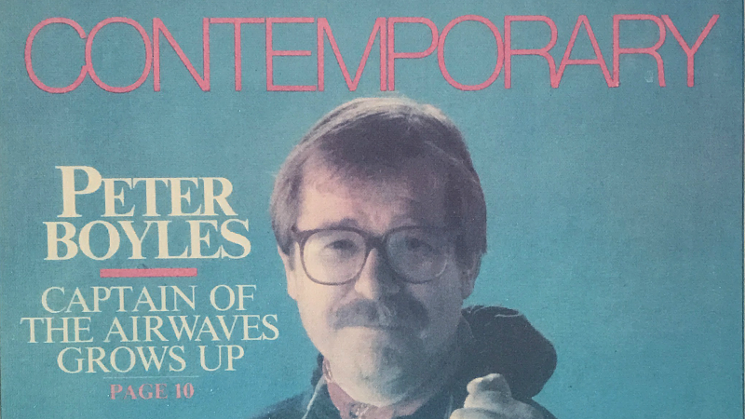

Peter Boyles on the cover of the Denver Post magazine Contemporary in 1984.

Courtesy of Peter Boyles

There's something called issues talk. It could be considered hot topic of the day. I was much further left than I am now, but everybody was angry. Radio was angry. If you think it's angry today, it was much angrier then. And it was a liberal outlet. Mike Rosen, to his credit, was probably the first conservative on-air voice here — and then Rush Limbaugh hit and it changed everything. Limbaugh saved AM radio.

Alan was a screaming liberal, and I wasn't as left as he was, but I was certainly left of center. Gary Tessler, Rick Barber: all these guys, we were products of the ’60s. And to Rosen's credit, he changed it, and then Limbaugh really changed it, and it all began again, where the media gets sectioned into mainstream liberal radio, mainstream conservative talk. And this was before the arrival of the Internet. We went about picking fights on the air, locally. Always with mayors and city councilmen.

Let's talk about your philosophical transition. At what point did you change your views, and was there some kind of event that led to it? Or was it more of an organic evolution?

Mark Twain had an adage about his father. I'm paraphrasing, but Twain said his father thought one way and he thought another way, and five or ten years later, he was amazed by how smart his father had grown. And there are quotes about being liberal when you're young and conservative when you're older — and I think it's true. I think becoming a father was part of it for me — and getting sober was a real significant part. It was 31 years ago that I got sober. Sobriety was a major event in my life. I don't talk that much about it, but it was. And through all of that, I've met some remarkable people.

I'm not a Republican. In fact, I'm repulsed by the Republican party. I think I'm more of a Prairie Populist kind of a guy. I distrust the media, and distrust foreign-policy decisions, I distrust multinational corporations. But at the same time, I totally distrust the Democratic Party. Both of those sides in this equation have gotten this country into enormous problems.

How did your fans handle your ideological shift? Did some people feel betrayed?

Back then, talk radio was really in its infancy. Remember, talk radio has some deep roots, but its real arrival on the scene as a political mover and shaker is pretty recent. So when the explosion of talk radio hit and talk formats sprung up everywhere, it was conservative. So I was more there waiting for what happened — not for ratings or revenue, but because of my own personal feelings. I could have been whatever I wanted to be in 1978 or 1979, because no one paid attention to radio. Radio was fun, it was Hal and Charley, it was good times, it was eight hits in a row and all the beer you could drink for a dollar and giving away a car on the morning show — all the things that are gone.

Radio's changed so dramatically in the last fifteen years. Radio was fun when I started out; it was a kick in the ass. But it was a lot of unbridled drugs and alcohol and crazy stuff people did and trips, and you got trade-out cars, and you could do pretty much what you wanted as long as you delivered the ratings. And now ratings aren't really that big of a deal, because nobody really has them. Kids have their own radio stations in their iPhones. The DJ-format thing is totally being pushed away.

You mentioned earlier picking fights with city officials, and over the years, you haven't had a lot of nice things to say about Denver mayors. Has there been one you liked?

I really liked Michael Hancock until we got bootlegged the call sheets from the whorehouse. His cell phone number was on it, and that was the last time he talked to us. I dialed the number on the air and the cell phone answered. That was given to us by some of the people from Denver Players and Denver Sugar. But that doesn't bother me. I'm more into the thing of "Don't tell me who likes you. Tell me who doesn't like you and I'll know who you are." Would you rather be in the Hall of Fame or would you rather be a rebel?" And I'd rather be a rebel. I'm not looking to do radio shows about those people and have their blessing. I don't need the approval of the governor or the mayor to do a radio show.

One of the stories in the last twenty or thirty years with which you're most associated is the JonBenét Ramsey case. Your approach to it has been controversial from the beginning. How would you describe how you've gone about covering the story and some of the things you've learned along the way?

We took on the Rocky Mountain News, aka the Ramsey Mountain News, and we took on Channel 9 and Paula Woodward. We took on everybody, because by the third day, it was quite apparent that somebody that was in the house, and not an intruder, killed that little girl. It was overwhelmingly evident that Patsy Ramsey was the murderer, and there was a staged coverup. But it was cool to watch how the Ramseys manipulated the Front Range media, how lawyers manipulated people, how threats were made to media people. It was just an amazing experience. The fact that they wouldn't take lie detector tests and would never be interrogated apart from one another. I had friends of mine from law enforcement who said, "Peter, this ain't a whodunit." And to watch the Rocky Mountain News and Channel 9 and Paula Woodward; they were despicable through all of that. But now we know through the grand jury — and great work by Charlie Brennan — that they wanted to indict John and Patsy. I rest my case.

The JonBenét Ramsey case is seen as seminal in the development of tabloid television and modern cable news. Could you tell that was going on as it was happening?

Sure. I was taken to a restaurant and shown a copy of the ransom note. Not the ransom note itself, but a copy of the ransom note. I was shown it by someone very inside the investigation. I said on the air that I'd seen the note, this three-page note. And I was approached by all the tabloids, who offered diamond rings to my then-wife and everything else. I knew something was going on, and they did a total end run on the Denver Post. The Rocky Mountain News just became the mouthpiece for the Ramseys and their lawyers and others. Channel 9 was probably worse, but everybody seemed to be afraid of that story. I never understood that, because there was a dead little girl. But there seemed to be an endless supply of videotape of her performing. I don't know who was handing it out; I suspect Patsy was bootlegging it to the media, because on some strange level, she loved the attention. But every night there was another performance, with this little girl being sexualized by her mother and God knows who else. And that drove the story.

I've always said, compare and contrast the disappearance and murder of Aaroné Thompson, a little African-American kid from Aurora, and JonBenét Ramsey. It was overwhelming how great a job the Aurora Police Department did. They put Aaron in prison for the rest of his life, and his live-in girlfriend, who probably was the killer, died. Patsy Ramsey has died, too, and John wears the scarlet letter. But just compare and contrast how the media treated the Thompson family and how they treated the Ramseys. And we were in the middle of the whole thing. You would have thought I'd killed somebody's dog. They were on national television every night, and my heart was broken when Alex Hunter didn't indict them, because he could have.

Another topic you're associated with that has stirred up a lot of controversy on both sides of the issue is immigration. You've talked about how you've been called a racist because of your stance, but you've shrugged that off in a way most people don't. Why does that word stop so many people? And why has it not stopped you?

It's a politically correct charged crime. It's "I accuse." And in modern media, all you have to do is accuse someone of being a racist or a sexist or a homophobe or an Islamophobe, which is another one of those politically correct invented crimes that I've been accused of being, too. And when I would invite people to come and talk about topics like that on the radio show, they would say, "I won't appear on your hate show," which is another way of saying, "I can't deal with you." So it's an easy charge to scream, but I think it's ridiculous. If all you can do is call me a name — if that's all you've got — that's not enough.

Your take on the birther story has also led to a lot of criticism. Do you regret your position about that in retrospect?

No. There are two stories after the Ramseys — two stories that have driven the radio show. The first was that George Bush and Dick Cheney lied and there were no weapons of mass destruction and no terrorist camps in Iraq. Those men started America's longest war. No one will ever know how many people have died and how much money has been spent. George Bush lied. There were no weapons of mass destruction, no terrorist camps. He's the worst president of my lifetime. And the other story was: Barack Obama's life story is a fabrication. Barack Obama's life story — his credentials, his bona fides — has been suppressed, lied about, remanufactured. He ran a con on the United States of America. But if Barack Obama is a grifter, the Bush and Cheney people ran the long con.

Even Donald Trump has backed off the birther issue. But do you still feel there's substance to it? And do you feel so many people have abandoned that issue only because it doesn't matter anymore?

From time to time, we revisit it when something new happens. He's not president anymore, and it doesn't matter. But the time will come — history will show that we were justified in what we said. His birth certificate — just ask yourself when you ever saw a birth certificate that said "African" as a race. It says father's race: "African." Now, people have searched all the birth certificates of African-American kids, and sometimes they'll say "colored," sometimes they'll say other things. But no one's ever been able to find another birth certificate that says "father's race: African." African is not a race. There are Semitic Africans, there are black Africans. It's like saying "father's race: North American." But when they came up with that politically correct, manufactured, phony birth document, they couldn't say "colored," they couldn't say "Negro," so they came up with African. There's not another birth certificate like that for a black kid born in Hawaii. That's only the beginning on that birth certificate. And it goes on. Suppressed college records, high school records, grade school records. The guy's whole life is a con.

You mentioned your exit from KHOW. Looking back at it, do you feel the station treated you fairly? Or do you think things could have and should have been done differently?

My contract was expiring, and they had offered a lot less — doing what they're doing now, which is squeezing people out of all the money. They were willing to talk, but they weren't willing to do what I wanted. And I've got to hand it to them. They were a lot smarter than me. I gave them the rope and they hanged me with it. There are a couple of people who don't care to talk with or about who screwed me after I was fired. But it's okay. After all those years, there was only the money in my 401K. I never got any severance pay, no sick-leave pay. They just put me on the street. And you know what? I'm cool with that. Because we've come back and played in the game again. You can't walk through life backwards. If it happened, it happened. Working for Lee Larsen over at Clear Channel was one of the greatest experiences I've ever had in my life. So what good does it do? It doesn't do any good.

KNUS has a smaller footprint than KHOW or the Clear Channel stations. Is that frustrating to you? Or do you feel you've helped build up KNUS to the point where you're still having an impact?

We've done well in the mornings. In the ratings, which I'm not supposed to know, we're doing really well. We're selling ad space, we're selling time. And at this point in my life, I'm really happy to go to work. It's fun, I work with a great team, I don't have to worry about somebody looking through the glass from the other side of the control room because I've angered one or more of their friends — somebody they have to play golf with or someone who's in their inner circle. I don't have to worry about that, and that's a relief.

Scottie Ewing, I was the only radio guy he agreed to talk to. He agreed to come in and do an interview on the air about Denver Players and Denver Sugar. The night before he was set to come into the studio, I got a call from the bosses. They didn't want him in there. I said, "This guy was running four houses of prostitution that catered to Denver's rich and famous. There isn't any question about it. And it included the mayor, Michael Hancock." But they were threatening me, saying they didn't want him there. I even threatened to quit my job. And in the morning, when Scottie Ewing came in, management sent a guy to sit in the room with me, like a babysitter. I threw the guy out of the room. I said, "Get out of here right now." He left and we did the interview. I defied them, and I thought Ewing was the hottest property in town.

Now Lee Larsen's gone and there's new management. They wanted to put a little babysitter in the room so I wouldn't say anything wrong. And I think that was the beginning of what was going to be the end for me.

At KNUS, do you feel you have as much freedom, if not more freedom, than you've ever had?

I always had freedom. Back in the salad days at KOA, when Alan was alive, we had total freedom. We worked for Joel Day, and he was grand. Working for Lee Larsen was grand. There were times when Lee would come in after the show and say, "What the hell did you do?" But he never told us what to do before the show. And by the end at Clear Channel, those guys were telling us what they wanted us to do. The Scottie Ewing thing was really telltale. The mayor was clearly having sex with women for money. What were they worried about? I never got that one.

Do thoughts about the future of radio impact what you do on a day to day basis?

I don't know what radio is going to turn into. On the coast now, there's FM talk. But one of the real problems is looking for talent. When someone like Rosen walked in the door, he was good to go. And he was really good, but he wasn't a radio fellow. He hadn't been a traffic reporter or a disc jockey. He hadn't read the news. That's the stuff that we did. Berg wasn't that, either. He was a disbarred lawyer who had a clothing store and a shoe store. He just dropped into a radio station, sat down in front of a microphone, and he got it — he got it more than anybody got it. He had nothing in terms of radio, but he got it. Now we have guys like Dave Logan. He played pro sports, and then afterward, he got into radio and he did it really well. But the old disc jockey guys, the Hal Moores and the Bob Lees.... I don't know if they could have transferred themselves into the talk format, but they were great disc jockeys.

I'm too damn old. But my worry is, there's no bench. When I look down the bench, there's no bench. I don't know where they're going to get the talent. Remember, there are no more radio schools, there are no more disc jockeys, there are no more places where guys like me can learn. But having said that, the formats are folding, all the people at big stations are taking huge pay cuts. This is the work of the money managers who've taken over the radio stations and are squeezing them like a sponge. It's happened to television and newspapers, and it's happening to radio, too. The Internet has killed everything, and that's good. Some of that stuff needs to die.

You've called yourself the most dangerous person in Denver radio. Is that a title you take pride in?

That's a steal. Some of the greatest fun I've ever had in my life is that I got to work in professional wrestling. And I worked for Verne Gagne in the old AWA [American Wrestling Association]. I got to introduce Dick the Bruiser once in a tag team match with the Crusher. And he said, "Here's how you introduce me. You introduce me as the most dangerous man in professional wrestling." So that's a steal from Dick the Bruiser. And it dawned on me, I should steal that from Dick the Bruiser. I think we say, "The most dangerous show on Denver radio." It's fun to say, but it's not original.

Setting originality aside, is that a goal you aspire to? Do you want to be the radio show that folks know won't soft-peddle anything?

I think you have to. It's what the Internet does, it's what tabloids do. Where's the investigative journalism that really goes after the fat cats and the money guys and how DIA was created and who left office because he was sleeping with other women? Those are stories we've done, and they're stories the mainstream press in this city won't go near.

There are plenty of people who dislike the show — who hate the show when I talk about Barack Obama but love the show when I talk about George Bush, and vice versa. And I think that's the balance you seek. We seek to put this thing where it belongs and not be a lapdog — not be a Republican lapdog or a Democratic lapdog or a conservative lapdog or a liberal lapdog. Just say, "Let's find the truth in here someplace."