On the night of September 23, 2017, it was pouring rain — not great weather for an indoor/outdoor event. Despite the elements, Lee Hurter was impressed with the evening’s turnout; at least five dozen people had packed into a space known within Denver’s activist circles as the “Knox House,” located on Knox Court in the Barnum neighborhood.

The event was a pop-up vegan cafe, with some food prepared on site and other vegan delicacies donated by the WaterCourse Foods, a popular Capitol Hill restaurant. Attendees were handed a menu from which they could purchase items à la carte, and the orders were delivered to dining tables by volunteers. Outside on the patio, where organizers hastily erected tarps to provide protection from the pelting rain, there was additional entertainment: a drag show, political hip-hop performers, and a silent auction with such donated items as massage treatments, acupuncture appointments and handcrafted jewelry.

All of the fundraising efforts would benefit Queen Phoenix.

Over the previous ten months, the activist, whose legal name is Dezy Saint-Nolde, had gained widespread recognition in Denver for her rousing speeches at marches and rallies, many of them in protest of the Trump administration. But Queen Phoenix was also in serious legal trouble: She faced eight charges related to her business offering homemade edibles and marijuana concentrates.

Phoenix told supporters — and the media — that she’d been under the impression that she could legally gift up to an ounce of cannabis in exchange for donations. The Denver District Attorney’s Office didn’t see it that way; it claimed that Phoenix was running an unlicensed and illegal narcotics operation.

Hurter staked a middle position. He didn’t believe Phoenix was 100 percent innocent, but it did seem like prosecutors were going after her extra hard, threatening to put her behind bars for what he considered a relatively benign business venture. Were the charges really in retaliation for Phoenix’s large, sometimes disruptive protests? That was Phoenix’s stance, and Hurter thought there was some validity to the argument that she was being targeted for her activism. He was glad to help raise money for the legal defense of a fellow activist, even though he didn’t know her that well.

But when Hurter started talking to other attendees at the pop-up event, he noticed something odd.

“How do you know Queen Phoenix?” Hurter asked a woman who’d made silk-screened T-shirts featuring a posterized image of Phoenix with the spinoff phrase “Good Save the Queen.”

The woman replied that she’d only interacted with Phoenix at a handful of demonstrations; like Hurter, she was helping because of a greater allegiance to Denver activists in need.

Oh, weird. So she don’t know Dezy that well, either, Hurter thought.

When he spoke with some of the performers, Hurter heard the same story: They had seen Phoenix at various demonstrations, but didn’t know the activist personally.

Half of the event’s attendees were part of an activist collective called the Affinity Group, which was just getting off the ground at the time (and is now defunct). The Affinity Group had chosen the pop-up cafe as one of its first calls to action, but none of its members seemed to have a personal relationship with Phoenix. Maybe no one is close with her, Hurter realized.“It may be gloomy out, but it warms my heart to see everyone here,” Queen Phoenix told the crowd.

tweet this

But Phoenix certainly appreciated the turnout. “It may be gloomy out, but it warms my heart to see everyone here,” Hurter remembers her saying in a speech toward the end of the evening.

The event was a rousing success. Around $2,000 was raised for Phoenix’s legal defense — $1,500 on credit cards and $500 in cash. An additional $3,835 was crowdfunded on a social-justice website, $300 of which came from Hurter.

The first day of Phoenix’s jury trial in Denver County Court was set for October 16. She did not show up. She was charged with a failure-to-appear, and a warrant was put out for her arrest. She’s been missing ever since — along with all of the money that was donated.

Phoenix’s disappearance has raised all sorts of questions: about her past and about the nature of leadership within Denver’s activist circles, as well as the broader issues of the way in which image and reputation can be cultivated — and created outright — online.

But the main question still on everyone’s minds: Where is Queen Phoenix?

Rather than mope around on November 9, as some of her friends were doing, Jones decided to organize a protest of the president-elect. She took to Facebook, intending to create an event and invite activists she knew, but noticed that someone named “Queen Phoenix” had already created a Facebook event that was racking up thousands of attendees. Scheduled for November 10, the protest was titled “Denver Unites for Better Than Trump.”

“Bummer,” Jones thought, realizing she was beaten to the punch. There was no reason to create a competing event — it would never generate as many attendees — so Jones joined the thousands who’d already clicked “going” on Queen Phoenix’s protest.

The demonstration the next night, November 10, drew thousands. The crowd hoisted signs decrying the new president and marched along the 16th Street Mall, then onto the State Capitol grounds. Later, an offshoot group of dozens of protesters climbed onto Interstate 25 near Sixth Avenue and shut down the freeway for half an hour.

An unknown but charismatic figure led the main procession. Sporting a large Afro and a bright-red dashiki, Queen Phoenix was an electrifying presence. Linking arms with the people beside her, she led chants as the march snaked its way around downtown. When Jones saw her, she thought that Phoenix looked like a natural-born leader; she had to meet this person.

Suzanne Gould, another demonstrator, felt the same. Both would join an organization that Phoenix created right after the November 10 protest called Community for Unity.

This was the 59-year-old Gould’s introduction to activism, and she couldn’t have been more fired up. “She brought me into it, and she brought other people in as well,” Gould recalls.

Phoenix was apparently as surprised as anyone by her sudden notoriety. “When I first started that event, I thought, ‘Maybe 20 people will show,’” she told Out Front. “Literally, I thought 20 people would show up and it would be a group hug, a little bit of a walk, and a little support session.”

But it turned into much more. After November 10, many activists — seasoned and not — wanted to be part of Community for Unity. The group began organizing more marches, including a large protest on Inauguration Day, January 20, the day before the Women’s March that was being organized around the country. Phoenix’s task on January 20 would be marching a group of students from East High School down Colfax Avenue to a rally in front of the Capitol.

Jones, who became part of the inner circle of Community for Unity organizers, attended planning meetings at Phoenix’s house in Athmar Park. That’s where she met Phoenix’s wife, Meghan Saint-Nolde, and Tylone Evans. The three of them were living together, and Phoenix was pregnant with Tylone’s child. In Jones’s eyes, the trio was a very loving family.

More than a year before, Phoenix and Meghan had moved to Colorado from Milwaukee, where Phoenix, who then went by “Dezy” (her maiden name is Desiree Brown), was a musician. A Facebook page under her artist moniker, Lezy Dezy, describes her as “a Milwaukee-based lesbian musician with a distinctive mix of acoustic alternative rock, folk, and hip-hop who is unstoppable with a looper.”

On the Lezy Dezy page, Phoenix frequently wrote about her romantic relationship with Meghan, whose maiden name is St. Ledger. She also posted an article from online magazine OnMilwaukee, which described their wedding on October 17, 2014.

“This is the story of two women who fell madly in love and, against all odds, had the ability to legally exchange wedding bands and begin a life together as spouses,” the article reported.

That love started when Phoenix and Meghan met at a drag show at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Both were born in 1987, and each had struggled with sexual identity during adolescence. According to OnMilwaukee, Phoenix had come out three times: “First as bisexual. Then gay. Then as androgynous, meaning Dezy prefers genderless associations and pronouns, such as: they, them and theirs.”

“I’m just going to warn you, a lot of my songs are about love. What can I say? I’ve always been a hopeless romantic.”

tweet this

Meghan told OnMilwaukee, “I didn’t give my family a chance to give their feelings or opinions. I wrote a letter to my dad saying: This is who I am, and if you don’t like it then I’m ready to be disowned.”

Even after they met, though, Phoenix struggled with identity and depression. According to the article, while she and Meghan were dating, she attempted suicide for the third time since she was sixteen years old. Meghan learned about that when she got a call from a hospital and was told that Phoenix had swallowed a bunch of prescription pills and was on 24-hour suicide watch. The ordeal ultimately brought the two closer together; they ended up being among the first couples to be married in Wisconsin after it became legal in the state in November 2013.

The pastor who conducted the ceremony, Rachel Young Binter, remembers the wedding as a joyous affair. She didn’t keep in touch with the couple, though, and says she doesn’t know why Phoenix and Meghan later moved to Colorado.

Jones remembers Phoenix mentioning some kind of family dispute precipitating the move. (Neither Phoenix’s nor Meghan’s family members responded to Westword’s requests for comment.)

Whatever the reason for the move, the couple was definitely interested in Colorado’s burgeoning cannabis industry. On another Facebook page that Phoenix did not delete after disappearing (unlike several others, including the Community for Unity and Queen Phoenix pages), she chronicles the first marijuana business that she and Meghan set up in Colorado in 2015, called “A 420 eXperience.”

Half of the posts on the Facebook page, started on September 30, 2015, contain photos of Phoenix or Meghan smoking pot. Others posts show gourmet, THC-infused dishes they’d cooked, including cannabis tacos. Over the course of a year, they hosted a few meet-ups and events, and the single (five-star) review of the business reads, “They’re amazing and really will do anything within reason to make sure your time is amazing!”

Eventually, the aspiring ganjapreneurs decided to rebrand the company as the Rising Phoenix Community, with a focus on manufacturing phoenix tears, which are highly potent THC extracts. The Facebook page and website for the Rising Phoenix Community have been deleted, but a final post written by Phoenix on the 420 eXperience page, on August 2, 2016, describes the rebranded business venture:

“Attention everyone: We will be closing this business and opening my new, refocused business. When we made A 420 eXperience, we were more focused on the cannabis tourism industry. Now that we are focused on reviving and healing Earthlings with Phoenix Tears and the magical powers of cannabis and plants, we decided we need an entirely new image, vision, and movement.”

But as both Phoenix and Meghan would find out, reviving and healing Earthlings would land them in a lot of legal trouble.

After the “Better Than Trump” protest put her on the map as a Denver activist, Queen Phoenix continued to run her cannabis operation to make ends meet. Its website offered free delivery of cannabis products, and on December 27, 2016, Phoenix went to the Starbucks on the corner of West Colfax Avenue and Kalamath Street to meet with a client.

She had already been corresponding with this particular client, a woman, for about three weeks, and it wasn’t their first exchange at the same Starbucks. On December 13, the woman had given Phoenix $1,000 in cash in a plain white envelope in exchange for marijuana flower and edibles.

The follow-up meeting on December 27 was quick; after another cash-for-cannabis transaction, the client mentioned that she’d made some holiday treats, and suggested that Phoenix follow her to her car so that she could give her a tin of cookies.

The client turned out to be an undercover cop, Jessica Delarow with the Denver Police Department’s Vice and Narcotics Bureau.

“She hugs me, then says she had brought cookies for the holidays and went back to her vehicle to retrieve them,” Phoenix told Westword last January. “Next thing I know, I see an officer with a gun pointed at my stomach. At least six squad cars were in the lot and blocking both entrances.”“Next thing I know, I see an officer with a gun pointed at my stomach. At least six squad cars were in the lot and blocking both entrances.”

tweet this

Phoenix was placed in handcuffs, and Tylone Evans, who was waiting in a nearby car, was also arrested. (A week later, Meghan was arrested and charged with illegal marijuana activity as well.)

After Phoenix and Tylone posted bail and returned to their home in Athmar Park on December 29, they found that the place had been turned upside down. Denver police officers had raided the home on December 27 with a signed search warrant. Trash was strewn all around the rooms, drawers were pulled out of dressers and flipped over, and electrical wires on the surveillance cameras Phoenix had installed were cut.

In a January 17, 2017, Westword story, Phoenix defended her marijuana operation, explaining that she thought she could gift certain amounts of cannabis in exchange for donations. “Most people see marijuana as medicine,” she said. “We’re in Colorado, this shouldn’t be happening, because it’s not like we had 200 plants and were running an illegal operation. I know that I was attacked for my activism.”

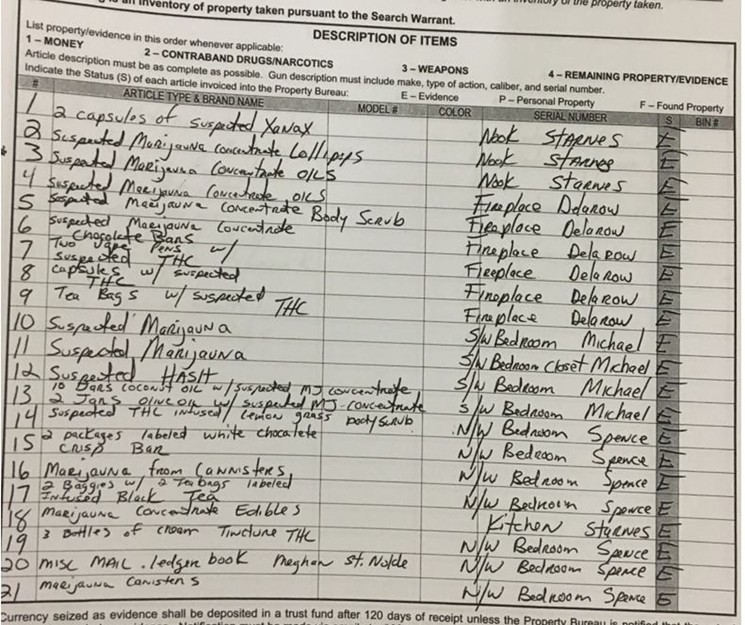

An affidavit in support of DPD’s search warrant was not available at the time, but a redacted version was made public in February. It describes more than a dozen types of cannabis products that were seized from Phoenix’s house, and includes Delarow’s description of how she conducted her investigation:

“On December 7th, 2016, your affiant received information from a law enforcement source that ‘Dezy Saint’ on Facebook was selling marijuana,” the account begins. Delarow then found the Rising Phoenix website, which “included a menu that featured products and prices (Ex: edibles, capsules, cooking oil, topicals/salves and pre-rolled joints) that were available for a ‘donation.’”

“On December 7th, 2016, your affiant received information from a law enforcement source that ‘Dezy Saint’ on Facebook was selling marijuana."

tweet this

On December 9, Delarow exchanged her first text messages with Phoenix, arranging to buy $200 worth of flower and edibles. Around 3 p.m. that day, Delarow was instructed to go to the Wendy’s at East Sixth Avenue and Sherman Street, and look for a silver Toyota Highlander in the parking lot. When she spotted the vehicle, Delarow walked up to the driver’s-side window and found Meghan. “We’ve been doing this illegally for four years, and legally here in Colorado for a year and a half,” she said Megan told her.

Delarow said that at her first meeting with Phoenix, at Starbucks on December 13, she bought $1,000 worth of cannabis products and had Phoenix explain the alcohol-extraction process used to make phoenix tears. After she filed her affidavit and the search warrant was approved, Delarow then met Phoenix at the same Starbucks on December 27 and arrested her and Tylone there. (Westword contacted Delarow for this story; she said she needed permission from her higher-ups to talk. That request was denied; DPD’s public information officer says Phoenix’s case cannot be discussed because it’s an ongoing investigation.)

Phoenix was charged with five felonies and three misdemeanors related to her cannabis operation.

At a pretrial hearing on March 21, Phoenix told Westword that she had finally obtained a copy of the search warrant affidavit and was upset that there was no mention of her activism. But she claimed that that proved an even broader conspiracy: The DPD was covering its tracks and hiding evidence that it was targeting her for her disruptive demonstrations.

In the spring of 2017, that’s what Phoenix’s most ardent supporters believed. But at the same time, she was also starting to create fissures in Denver’s activist community.

Phoenix was not shy about reaching out to other Denver residents for help. She held her first legal fundraiser at Illegal Pete’s on South Broadway on January 7, 2017, and posted this note on Facebook for those who attended: “Looking forward, I feel a new determination to fight this case and expose the Denver Police Department for their wrongful and aggressive surveillance of activists. I promise to stay strong against this psychological warfare and stay committed to this movement just as I have in the past two months.”

In February, Jones started reaching out to other, more established activist organizations to see if they would lend assistance to Queen Phoenix. Their responses were surprising...and cold.

Denver SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) and Black Lives Matter 5280 told Jones that they wanted nothing to do with Queen Phoenix. In fact, the organizations had been warned to stay away from her. (Both groups declined to talk to Westword for this story.)

Eventually, she figured out what was going on, Jones says: Another activist in town, whom she refuses to name, had been warning groups like Denver SURJ and Black Lives Matter about a website she’d found that contained concerning allegations about Phoenix. The website, which Jones says she saw but has since been deleted, was allegedly published by a Colorado farmer who accused Phoenix and Meghan of stealing money and a vehicle from him. “It was a personal website from a guy with a vendetta against her,” Jones adds."I feel a new determination to fight this case and expose the Denver Police Department for their wrongful and aggressive surveillance of activists."

tweet this

When Jones pressed Phoenix for details, Phoenix gave her side of the story: When they first came to Colorado, she and Meghan had briefly worked on an organic farm; she was sexually assaulted by the owner of the farm, she told Jones. In retaliation, she blackmailed him, demanding his car and his money in return for not reporting him to the police.

When Phoenix heard about the website, Jones says, “Dezy had him take it down because she was going to sue him for slander.”

Phoenix’s arrest and marijuana charges only complicated the confusing situation created by the farm rumors. And then there was concern over Phoenix’s ego and political actions. Some local activists were annoyed that Phoenix, who’d seemed to come out of nowhere, was using her platform and growing numbers of followers to protest Trump rather than race-related issues such as police brutality.

Hurter says he heard plenty of chatter about how Phoenix seemed to focus on her image as much, if not more, than the issues that inspired her demonstrations. “Some of the critiques that I’d heard were, ‘Who is this person that showed up from out of town and all of a sudden they’re the center of attention and self-aggrandizing?,’” Hurter recalls.

Coming under increasing fire, Phoenix hosted fewer demonstrations as the months went on — even as she continued collecting money for her legal defense. The Denver District Attorney’s Office had offered her a plea deal: a Class 3 felony and up to ten years in prison. Phoenix turned down the offer, instead pleading not guilty to all eight counts against her. She told supporters that to have any shot at beating the charges, a public defender wasn’t going to cut it: She needed money for a private lawyer. A good lawyer.

Phoenix turned to Hurter, who had once reached out on Facebook Messenger offering to assist with fundraising. Hurter volunteered to set up a crowdfunding page for Phoenix on fundedjustice.com, using photos, a written description and bank-account information that Phoenix provided. “Our goal is to raise enough funds for a proper defense lawyer who understands the connection between Queen Phoenix’s peaceful activism and these exaggerated marijuana charges,” the mission statement read.

The online campaign racked up $3,835 from 101 separate donors, and the September 23 fundraiser at the Knox house brought the total to around $6,000.

Even with her case pending, Phoenix wasn’t done stirring up controversy. As the October 16 trial date approached, a teacher at Sky Vista Middle School in Cherry Creek, Asia Lyons, invited Phoenix to give a presentation about activism to her sixth-grade students. A handful of Cherry Creek parents heard about the talk, found news coverage of Phoenix’s pending marijuana case and threw a fit. Some of them showed up to complain at an October 9 school board meeting.

“We parents put the trust in every person that enters Sky Vista. That trust has been broken by Ms. Lyons for allowing a speaker who goes by the name Queen Phoenix to enter Sky Vista and speak to the students,” Michael Grube, a parent of two students, said during the public comment period.

“We feel like the district and school have let the families down,” added another upset parent.

But others came to the defense of both Phoenix and the teacher. The Aurora Sentinel quoted one teacher who said that “white privilege” in Cherry Creek was silencing minority voices. In online commentary, others pointed out that Phoenix was innocent until proven guilty, and that Lyons’s class was about social justice, so her choice of Phoenix as a speaker wasn’t off topic.

The Cherry Creek School District decided to place Lyons and another teacher on administrative leave.

Lyons told Westword that she does not have permission talk about the incident. According to Abbe Smith, communications director for the school district, the district conducted a full investigation and found that Lyons and another teacher had only failed to ask permission from the principal of Sky Vista before bringing in Phoenix as an outside speaker. Both teachers were issued a written warning, and are now back in the classroom teaching.

“Thank you all for the birthday wishes this week! It has been the most challenging and rewarding year on Earth yet."

tweet this

The incident highlighted just how divisive Phoenix had become...and her trial had yet to start.

By now, Hurter was having second thoughts about the recipient of his aid. A seasoned activist, he knew that other standout organizers in Denver built their followings with blood, sweat and longstanding ties in the community. Phoenix hadn’t done any of that. In fact, her real support network seemed to consist of Meghan and Tylone and their new child, Zion, whom they intended to raise genderless; they were all leaning on each other heavily as their trials approached.

Hurter wondered: Could Phoenix’s image be nothing but a social-media fabrication? It was obvious she hadn’t been in Denver that long, but on the web Phoenix had created the illusion that she was more connected than she really was. A power vacuum in Denver’s fractured activist community — and widespread concern after the November 2016 election — had made it relatively easy for her to use technology to fill some of the void.

On October 11, just five days before her jury trial, Phoenix posted this Facebook message: “Thank you all for the birthday wishes this week! It has been the most challenging and rewarding year on Earth yet. I also want to take the time to thank y’all for the support you’ve showered our family with throughout this past year. Now, it’s time for us to focus on protective, positive energy.

“With trial starting next week, I want to let y’all know that I will not be using facebook anymore. I have many reasons for this decision and it’ll be in effect almost immediately for our family’s safety and sanity. However, I would like to stay in touch with a lot of you. If you feel the same way, please send me your email address so I can reach out for future plans of action after trial.”

It would be the last time that many people heard from Queen Phoenix.

On October 16, the opening day of Phoenix’s jury trial, I showed up to courtroom 5C at the Lindsey Flanigan Courthouse at 8:30 a.m. “DEZY STNOLDE” was listed on the electronic monitor right outside of the courtroom. I entered and took a seat. Forty-five minutes later, when Phoenix still hadn’t showed, I knew something was up.

That afternoon, I tried calling Phoenix; her phone was disconnected. I emailed her and the message bounced back. I looked on Facebook and saw that the pages for Queen Phoenix and Community for Unity had been deleted.

I reached out to the Denver District Attorney’s Office and learned that Phoenix had been marked as a “failure to appear.” A warrant had been issued for her arrest.

“Is she on the lam?” I asked Ken Lane, communications director for the DA’s office.

“You are correct,” Lane responded.

On October 18, Meghan also failed to appear for a court hearing. By then it was clear that Phoenix, Meghan and Tylone had all left Denver.

Their disappearances left supporters reeling, especially Gould, who’d been inspired by Phoenix to become an activist. “I was surprised and shocked,” Gould says. “And I was disappointed for myself, too, because I was getting into organizing, and I felt like we were putting on marches and rallies that really resonated with people.”

Jones is also upset, but she wonders if she may have scared Phoenix away by telling her that the prosecutor in her case, Adrienne Greene, was cunning and ruthless; Greene had put one of Jones’s family members behind bars.

“Part of me feels guilty because I don’t know if anything I said was the reason she left,” Jones says. “She told me she was scared to death of the trial.”

Still, Jones also acknowledges that she may have been duped all along. “The rest of me is angry because she left us high and dry,” she admits.

The DA’s office says it has no more information about Phoenix’s whereabouts.“The rest of me is angry because she left us high and dry."

tweet this

In mid-December — more than a month after Westword reported Phoenix’s disappearance — two alluring emails arrived within an hour of each other.

One was from Kendra Brown: “I am the sister of Dezy St. Nolde,” the message read. “I saw the article about how she missed her court date. I have some information that may be useful. If you are interested, feel free to contact me with any questions you may have.”

The other was from someone who claimed to be a former friend of Phoenix: “Queen Phoenix is not coming back to Denver and is going to stay running from the cops. She had come to Wisconsin a week before her trial and bought a new phone with a new number. I do not know where she went after she left Wisconsin but she is definitely not heading back to Colorado. She packed up all of her stuff and bought an RV with money that was not hers fraudulently and is now on the run with her partner, Megan St. Nolde and her child’s father, Ty. She is planning to run from the cops for as long as she can. To the people who have helped raise funds for her defense, i pray that they can receive their money back as she will not use the funds for a defense lawyer….I know Dezy St. Nolde personally for many many years and know a lot of the destruction she has left in her wake including in Wisconsin as well.”

Both Brown and the second emailer agreed to speak with Westword. And then they, too, disappeared; they have not returned emails or phone calls.

So the mystery of Queen Phoenix remains, heightened by the fact that few activists in Denver will talk to the media, much less publicly raise concerns about particular individuals in the community. There’s a general understanding that this city has too few dedicated activists for groups like Denver SURJ and Black Lives Matter to expend their energy badmouthing suspected bad actors.

Would Queen Phoenix have been able to grab so much attention so quickly if activists had aired their concerns? Did the “leaderless” structures of many Denver activist groups and her own charisma make it too easy for Phoenix to establish a platform? And will all the people inspired to new levels of civic engagement and public demonstration now be disillusioned from taking further action?

And finally, the strange story of this unlikely activist still leaves the most important question:

Where is Queen Phoenix?