"If you want to call me an idiot, or if you want to call me a moron, for saying what I did, that's fine," he says. "But the idea that it's based in racism is quite unfair, in my view, and I defy anyone to find any pattern of that in anything I've done in my life."

As we've reported, the tweet, inspired by the Indy 500 victory of Japan's Takuma Sato, quickly sparked a backlash on social media from the likes of Gil Asakawa, a former staffer for the Post (and Westword). On Facebook, Asakawa wrote, "I worked at the Denver Post, I'm embarrassed to say. I wonder what my former colleague Terry Frei thought about my running the website that featured his sports coverage? Was he 'very uncomfortable' with me having power over his content? What's his logic for this now-deleted tweet? What does he feel about Italians, or French drivers, or Latino or African Americans behind the wheel? If his objection is because it's Memorial Day weekend, would he feel the same about a German (or Italian) driver winning the race? And does he have ANY IDEA about the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team, which fought — and died — during WWII and remains to this day the most highly-decorated unit in the history of the United States military????? What was he thinking?"

Frei quickly deleted the tweet and shared a lengthy apology in which he talked about Third Down and a War to Go: The All-American 1942 Wisconsin Badgers, a book he wrote in 2004 about the title team and the assorted players' subsequent experiences during World War II. He later amended the apology to remove the title after online critics accused him of trying to pimp sales.

But these actions didn't prevent Post supervisors from giving Frei his walking papers within hours. A statement posted under the names of publisher Mac Tully and editor Lee Ann Colacioppo reads: "We apologize for the disrespectful and unacceptable tweet that was sent out by one of our reporters. Terry Frei is no longer an employee of The Denver Post. It's our policy not to comment further on personnel issues."

They added: "The tweet doesn't represent what we believe nor what we stand for. We hope you will accept our profound apologies."

Afterward, local press observers wondered if the speed with which Frei was disappeared had something to do with the financial problems the Post has experienced under the ownership of Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund that's been on a budget-slashing binge for years; under Alden's watch, the editorial staff has shrunk from a previous high of more than 300 employees to fewer than one-hundred, and the paper recently announced that its newsroom will move from Denver to Adams County.

When asked if he thinks his gaffe was used as an opportunity for some impromptu cost-cutting, Frei, who spent thirty years at the Post over two stints, says, "I don't know, but I hope not — and I hope there's still a way to reconcile. Because I appreciate what all the Denver Post's various incarnations have done for me over the years. I'll always remain faithful to that."

He understands that he put Colacioppo in an uncomfortable position because of the tweet, which he explains by going into more detail about the tales at the heart of Third Down and War to Go.

"My father, Jerry Frei, was a college football player at Wisconsin in the 1942 season as a sophomore," he notes. "He played on the team that won a version of the national championship in an atmosphere that was pervasive around the country at the time, where everyone knew that before long, they were going to be involved in the fight against Germany and Japan. My father became a P-38 pilot flying an unarmed version either solo or in two-plane reconnaissance missions before bombing runs."

Late in his dad's life, Frei continues, "I talked to him about his involvement in the team and the war, and how everybody on that team had done pretty much the same thing he did. So I set out to research that for a book, and I learned about players like Dave Schreiner, who was killed during the Battle of Okinawa. I still have the picture wallet that was among his effects. And I've written many, many, many stories about Colorado-based athletes who also fought in World War II, and about my father, who flew 67 missions in the P-38. I can't explain how emotionally involved I feel after talking with so many veterans of the Pacific and European theaters, and about how proud I've been to tell their stories."

Memorial Day brought these thoughts to the surface for Frei, as did a planned trip to visit the final resting places of his father and mother. Hence the tweet, which he says was "a thought thrown out about a nation that my father specifically fought. It wasn't about race."

Many readers felt otherwise, and they let Frei know about it.

"The most jarring responses, and the ones I took most to heart, are the ones that talked about the heroic contributions of Japanese-American troops during the war," Frei allows. "To me, they weren't Japanese-American troops. They were Americans to me. And I would have said the same thing [on Twitter] had a German won the race on that day."

This explanation "is very complicated," Frei concedes, "and it's not meant to excuse anything. What I did was stupid. And what I most regret is dragging others through that, and for people seeing it as a racist response. I can assure you that it was not. I bear no ill will or hatred for the Japanese people today for what their government did seventy years ago. It's terrific that we've come so far since World War II and that Japan is now a friend and ally. I'm very appreciative of that. I realize that things have changed and that I shouldn't have said what I said and how I said it."

Likewise, Frei refuses to place any blame for what happened on pressure from the Post to connect with readers via platforms such as Twitter.

"We are encouraged to participate in social media — to be outspoken and maybe, in the overall picture, to be controversial," he acknowledges. "But I wasn't looking at it like that in any way, shape or form."

As for the power of the medium that swiftly amplified his error, "I knew about all that before," he says. "That's why I was so stupid. I understood it. I've seen it happen, regretfully, to others who didn't deserve to be judged by momentary lapses. And the viral nature of all this involves you being judged by people who don't understand the context of it. You think you're talking to your quote-unquote followers, both in the literal and figurative sense. It's an arm around your shoulder, and it's interesting to people who know you and understand the context. But you soon realize that it can so suddenly get beyond that realm — that you've gotten outside the little private room of people who understand your background and the context."

Days after his dismissal, Frei still isn't ready to bid a final farewell to the Post. "I regret that things ended this way, and I hope it doesn't have to end," he says. "I don't believe I should have been fired. I believe there should have been an alternative means to handle this, and I still believe there could be."

In the meantime, Frei doesn't want his career to be defined by "a 140 character tweet." In his words, "You can't write about World War II veterans in both theaters, European and Pacific — veterans who we're losing every day — and not feel emotionally drawn into it. That's my perspective. And I hope that will help people understand what happened. But I can promise you, it wasn't based in racism."

Here's an excerpt from Third Down and War to Go focusing on Schreiner's family learning about his sad fate.

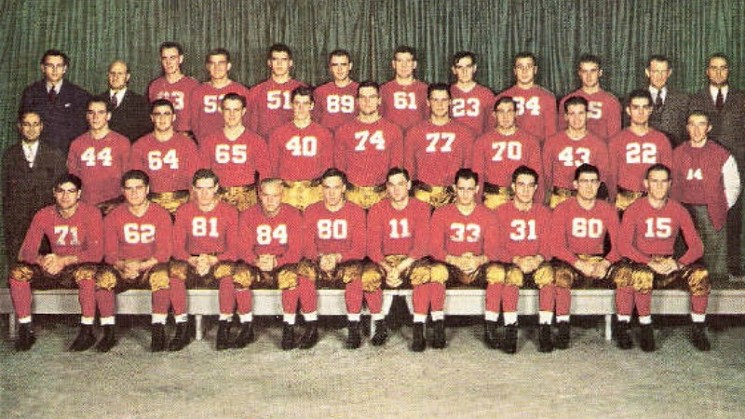

The 1942 Wisconsin football team. Dave Schreiner is one of two players wearing number 80 in the front row; he's roughly in the center. Number 11 next to Schreiner is Mark Hoskins, a childhood friend who was shot down and imprisoned in Stalag Luft III, known as The Great Escape camp. Number 74 is Bob Baumann, who was also killed in the Battle of Okinawa. Number 40 is future NFL star Elroy "Crazylegs" Hirsch, number 34 is Pat Harder, who went on to play in the National Hockey League, and number 65 is Jerry Frei.

Judy Johnson, Schreiner’s niece, was three and a half years old. “I was visiting my grandparents, which I did regularly, because I wasn’t in school yet,” Judy (now Judy Corfield) recalled. “My mother would send me there to keep them busy. I would spend a lot of time going back and forth to the Hoskins home, too, which was only a block away, especially after Charles died and Had was imprisoned. That kept everybody busy, taking care of Judy.”

The news arrived at the telegraph office the night of June 28, after the office was closed.

Everyone in Lancaster knew the Schreiners’ habits. They were up every day at 5:30 a.m. On June 29, the delivery boy arrived at the door a little after 7:00. He handed the telegram to Bert Schreiner. The proud father pulled the sheet out of the envelope.

70 GOVT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

8:41 P.M., JUNE 28, 1945

MR. AND MRS. HERBERT E. SCHREINER

216 SOUTH TYLER

LANCASTER, WIS.

DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU THAT YOUR SON FIRST LIEUTENANT DAVID N. SCHREINER USMCR DIED 21 JUNE 1945 OF WOUNDS RECEIVED IN ACTION OKINAWA ISLAND RYUKYU ISLANDS IN THE PERFORMANCE OF HIS DUTY AND SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY. WHEN INFORMATION IS RECEIVED REGARDING BURIAL YOU WILL BE NOTIFIED. TO PREVENT POSSIBLE AID TO OUR ENEMIES DO NOT DIVULGE THE NAME OF HIS SHIP OR STATION. PLEASE ACCEPT MY HEARTFELT SYMPATHY.

A A VANDERGRIFT GENERAL USMC

COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS

It is one of Judy’s earliest memories. She stood at the window and watched the delivery boy walk away, down the hill and back to the telegraph station. “The bad news has arrived,” Bert Schreiner told his wife and granddaughter.

He did the best he could to comfort Anne. Then he called the Hoskins and Carthew homes.

Doris Hoskins, Mark’s mother, knocked on the bedroom door. Mark and Mary Hoskins still were asleep.

“You’d better get up,” she said softly. “I have some bad news.”

Both Mark’s and Mary’s parents had already been over to the Schreiners’ home. When his parents told him about Schreiner, Mark cried.

Almost immediately, he was called to the phone. The caller was a shaken Harry Stuhldreher. The Wisconsin coach told Hoskins he was leaving for Lancaster immediately. Hoskins rushed over to the Schreiners’.

Mark still sobbed years later, recalling the day.