“The importance of some to Colorado, like La Folie or Juicy Bits, is pretty obvious, but there are a few that some of our newer Coloradans might not understand the overall significance of,” he says.

Tabernash Weiss, which hasn’t been brewed since the late 1990s, is one of those.

“Eric Warner started Tabernash Brewing after graduating from [German brewing school] Weihenstephan and cemented his Colorado legacy with Tabernash Weiss at his brewery, in what is now RiNo. A good friend of mine was the brewer and slipped us some of the yeast in our early Ska days. We thought we were going to create a similar beer and blow everybody’s minds in Durango,” remembers Thibodeau, who grew up in the Denver area drinking Coors. “But we learned a lesson: We sure as shit weren’t Eric Warner. The beer wasn’t even close.

“Years later, Adam Avery and I decided to try again with a special collaboration to commemorate an annual brewers’ bike ride we do [from Durango to Boulder]. We could recall everything about that delicious beer, how it tasted and how it made us feel, but we failed on the re-creation. Wheelsucker Wheat was our attempt — not bad, but not even close to Tabernash.”

Colorado wasn’t the first state with its own craft brewery, but it was certainly the cozy cradle where many of the nation’s most storied small and independently owned breweries were nursed into existence. Boulder Beer, founded in 1979, was granted the country’s 43rd brewery license (after Prohibition), while Wynkoop Brewing Co. co-founder John Hickenlooper went on to become Denver’s mayor, Colorado’s governor, a onetime presidential contender and today a candidate for U.S. Senate. New Belgium Brewing, founded in Fort Collins in 1991, is now the fourth-largest craft brewery in the nation. And, of course, there is Coors, a company run by a uniquely focused family in Golden since 1873 — one that now needs no introduction anywhere in the world.

Colorado is also home to Charlie Papazian, who created the Brewers Association and the Great American Beer Festival, which swoops into Denver this week for its 38th iteration. In 2010, there were fewer than ten craft breweries within Denver’s city limits; today there are around 75. Statewide, Colorado boasts between 400 and 420 breweries, depending on how you count them, contributing $3.3 billion to the state’s economy.

To honor Colorado’s brewing legacy, we’re spilling our list of the thirty most important beers in Colorado history. These aren’t necessarily beers with the most longevity or popularity, nor is this a collection of the best beers, or the best-selling beers, or the trendiest beers. Rather, it is a rundown of beers (sorted roughly by date) that changed the game, beers that other brewers imitated, and beers that people sought out with an unquenchable thirst.

These are Colorado’s most liquid assets.

Pre-1979

Coors has changed its label many times over the years, but the beer has always been Colorado-brewed.

MillerCoors

MillerCoors

Let’s face it: Almost every Colorado teen gained their beer legs on Coors Banquet. That yellow label, that fizzy flavor, that local connection. Over the decades, the beer has gone in and out of style, but it has never lost its mass popularity. In the ’80s, it was old-school, whereas Coors Light — the Silver Bullet — was the star, and Coors Extra Gold had a newcomer’s appeal. Fast-forward thirty-some years, and Coors Banquet is a hipster’s dream. It has cachet. It has history. And despite Coors’s current position as part of a multibillion-dollar worldwide conglomerate, Coors Banquet is still brewed only in Golden. That’s a fitting tradition for a 146-year-old brewery that dates back three years further than Colorado’s own statehood. Maybe there really is something in that Rocky Mountain spring water.

Coors Light

MillerCoors

Love it or hate it, Coors Light is a force to be reckoned with. The second-highest-grossing beer in the United States and one of the top sellers worldwide, Coors Light is known for being low in calories, alcohol and flavor — and big on advertising budgets. Coors launched it in 1978 to keep up with competitors like Miller and Schlitz, which were battling it out for supremacy in the light-beer market. The beer is said to have gotten its nickname from college kids who called the shiny silver cans “Silver Bullets”; the name stuck, and Coors incorporated it into the brand. Today, low-alcohol, low-calorie beers are back in style, and Coors Light seems to have once again struck an advertising nerve with its recent “Made to Chill” ads — a far cry from the Coors Light Twins promos of the early 2000s.

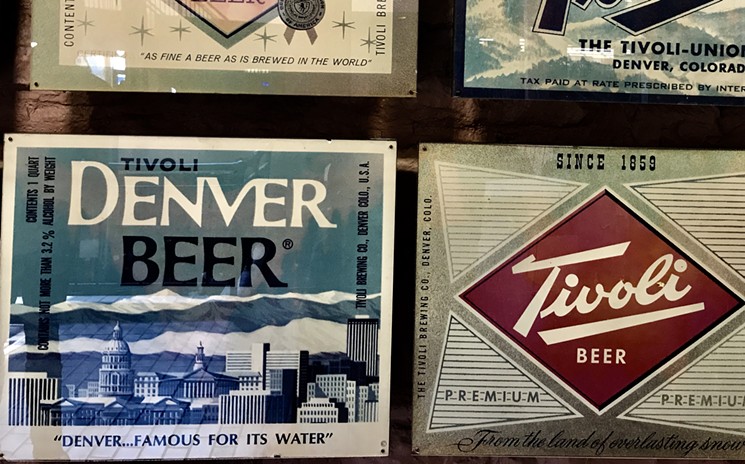

Denver Beer

Tivoli Brewing

Tivoli Brewing was officially founded in 1900 by John Good, but its roots go all the way back to 1859, a year after Denver was born around what is now Confluence Park. That’s when Good invested in Rocky Mountain Brewery, which was built near the site of the current Tivoli Student Union. By the turn of the last century, the brewery had become a major player in Denver, and by the time Prohibition hit Colorado in 1916 (three years before it took effect nationally), Tivoli was shipping its lagers all over the West. Prohibition, however, brought the company to its knees — as it did the majority of U.S. beer makers at the time — but Tivoli managed to survive, one of just three Colorado breweries to do so. By the 1950s, it was again going strong, and its brands, mostly German-style lagers, were a favorite in Denver. In 1965, the Good family sold the brewery to another local family, but a flood and a labor strike took a serious toll. Although Tivoli continued to turn out top-selling beers, it closed in 1969. Denver drinkers kept a soft spot in their hearts for Tivoli, though, and for Denver Beer in particular — the last of its much-loved brands. So much so that Tivoli was resurrected in 2012 by the grandson of a Tivoli stalwart and is now a thriving brewery.

The late 1980s and ’90s

Fat Tire

New Belgium Brewing

Aside from Coors, there is no beer more iconic to Colorado than Fat Tire. Reddish in color and malty in taste, it is the result of a cycling trip that company co-founder Jeff Lebesch took through Belgium in the late 1980s. Although its brother, Abbey Ale, won New Belgium a multitude of awards, Fat Tire is the one that caught on with consumers in the ’90s — and almost every other brewery at the time took notice, producing their own version of red or amber ales. Today, many people refer to Fat Tire, sometimes derisively, as a “gateway beer,” meaning it is the most basic thing you can drink as a bridge between industrial light lagers and fuller-flavored craft beers. But there is no denying how important that bridge has been or how many people decided to stop and stay on that comfortable connector. At one point not too long ago, bars in trendy East Coast cities where Fat Tire wasn’t yet distributed were buying it and serving it illegally to meet demand for the Colorado treat. But Fat Tire is now distributed in all fifty states, and so ubiquitous that drinkers often mistake the name of the beer for the name of the company.

90 Shilling

Odell Brewing

Like Fat Tire, Odell’s 90 Shilling is amber in color and approachable in flavor. But most of the similarities stop there. Instead of being inspired by Belgian beers, it takes its cues from the English and Scottish ales that brewery co-founder Doug Odell preferred. In fact, 90 Shilling began life as one of his first home-brewing recipes. Introduced at the brewery’s opening in 1989, it was a bold twist for most beer drinkers, and although it’s timid by today’s standards, it set the pace in Colorado and is still a regular go-to for many people, as well as a reminder of why craft beers were needed in the first place.

Rail Yard Ale

Wynkoop Brewing

Denver’s first brewpub started out making English-style cask ales, but it was an American amber ale inspired by a German Marzen that became its flagship: Rail Yard Ale. First brewed by early Wynkoop stalwart Tom Dargen to celebrate his wedding, the beer was named for the run-down train station across the street. But Rail Yard got plenty of people on board with its easy-going combination of malty sweetness and fruity esters. The Wynkoop and Rail Yard would change Denver, change craft brewing and change the state’s fortunes over the ensuing decades in ways that no one could have imagined in 1988, when it opened.

Laughing Lab Scottish Ale

Bristol Brewing

Laughing Lab Scottish Ale probably wasn’t the first beer named for man’s best friend, and it won’t be the last, but it embodied a certain (and now somewhat diminished) Colorado feel — dogs, Jeeps, the outdoors, independence, community — in a way that many other beers didn’t. Hailing from Colorado Springs, Bristol’s beers were at one time a must-have for bars and liquor stores across the state; Laughing Lab, for its part, won nine GABF medals over sixteen years. These days, the unassuming former star has faded into the background, but there is no denying the easy-sipping appeal of this malty beer, and it is as approachably delicious now as it was exotically delicious in 1994.

Isadore Java Porter

Mountain Sun Brewpub

As with music, tastes in beer have changed over time. Much of what blew people’s minds in the ’80s, ’90s or 2000s is considered quaint or boring today. But a few things continue to amaze, decade after decade. That’s why college kids keep discovering Led Zeppelin but not Men Without Hats, and that’s why Mountain Sun’s Isadore Java Porter has been a mainstay on this brewpub’s menu for 25 years. Concocted shortly after Mountain Sun opened in Boulder in 1993, Isadore was made by soaking huge amounts of coffee in wort (unfermented beer) — and it has sometimes come with a warning not to drink too much at the risk staying up all night. Rich, smooth and dark like coffee itself, the beer was a hit from the beginning, exploding people’s definitions of what a beer could be in a delightful way. And it continues to delight today.

Tabernash Weiss

Tabernash Brewing

When they close their eyes, beer drinkers who were around during the brief but very bright existence of Tabernash Brewing (1993-1997) can still taste its flagship weissbier. For many, it was the first flavorful beer they’d tried. For others, it was a perfect representation of an old style in a new place. Eric Warner, who developed and brewed the beer, would go on to write German Wheat Beer, a definitive style manual for the Brewers Association. A graduate of the famed Weihenstephan brewing-science school in Germany, he imbued Weiss with classic clove and banana notes and a foamy white head. Although many other breweries made hefeweizens at the time, none moved people the way that Tabernash’s did.

Blue Moon Belgian White

Coors Brewing

First conceived by Keith Villa, Coors’s promising young Ph.D., and first brewed in 1995 as Bellyslide Belgian White by Wayne Waananen inside the Sandlot at Coors Field, Blue Moon began its life as the beer giant’s ugly stepchild. A passion project of Villa’s, it was a beer that had more flavor (coriander, orange peel and Belgian yeast), more class (those tall glasses and orange slices) and a boundary-pushing hazy look (everything old is new again). But Blue Moon eventually caught on, and when it did, it couldn’t be stopped. The beer is now one of the top twenty bestsellers in the nation and can be found in more than thirty other countries. It is also often credited with helping to wake up America’s palate on a much larger scale than what the small microbreweries of the time were achieving. It has inspired many imitators, plenty of jokes and a raft of other flavored Blue Moon beers, not to mention its own brewpub in River North. But the beer has left a legacy that is uniquely tied to the heart of Denver.

Doggie Style Classic Pale Ale

Flying Dog Brewing

Developed in 1991 as one of Flying Dog’s first beers, Doggie Style got immediate attention when it won a gold medal at GABF — and the brewery moved from Aspen to Denver to expand. But the quality of Flying Dog’s beer took a back seat to the company’s marketing later in the 1990s when the Colorado State Liquor Board forbade the brewery from using the motto “Good Beer, No Shit,” on its bottle labels — labels that were designed by Hunter S. Thompson’s friend and colleague, Ralph Steadman. The case landed in the national spotlight as it wound its way through the courts; in 2001, the Colorado Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the brewery and its First Amendment rights. Flying Dog left Colorado in 2008 for Maryland, angering many of its local fans, and went on to face many more freedom-of-speech battles in other states for labels and names like Raging Bitch. But Doggie Style, hoppier than most pale ales and good enough to win a second GABF medal in 1999, retains its frisky reputation for taste as well as iconoclastic marketing.

Hog Heaven Barleywine

Avery Brewing

The story goes like this: In 1998, Adam Avery’s four-year-old brewery wasn’t doing very well. Although other breweries’ fruit beers, wheat beers and pale ales were flying off the shelves, Avery’s weren’t catching on. So Avery decided to make a brew that really moved him, a beer that had so much alcohol and was so hoppy that the Brewers Association had no way to classify it at the time. That’s how the 10 percent ABV, 102 IBU Hog Heaven Barleywine was born, and it would change everything for Avery. The brewery followed up with a series of boundary-pushing, style-defying, high-alcohol beers that earned it a reputation far outside of Colorado. Avery, now owned by Mahou San Miguel, has mostly left those beers behind, but it will always be remembered for having changed the palates and mindsets of beer drinkers in Colorado. Hog Heaven is still made, though it’s now classified as an imperial red IPA.

The 2000s

La Folie

New Belgium Brewing

In 1996, Belgian beermaker Peter Bouckaert moved to the United States to take over as the head brewer at New Belgium Brewing — and he brought his love of Belgian sours with him. A few years later, Bouckaert acquired his first wooden barrel (known as a foeder) and created La Folie Sour Brown, a groundbreaking brew on this side of the Atlantic. It turned out well: New Belgium won a GABF medal in 2000 in the Belgian-Style Specialty Ales category for La Folie. To illustrate how much things have changed, there was no sour-beer category that year, while there are more than fifteen today. La Folie is still one of the highest-rated sours in the country, among what are now hundreds of sour varieties.

Hazed & Infused

Boulder Beer Company

Like Tabernash Weiss and Bristol Laughing Lab, Boulder Beer Company’s Hazed & Infused is one of those beers that changed what beer could be for many people. Some can distinctly remember the first time they had it, and most remember the effect it had on them. First produced in 2001 as an experiment, it was brewed with three hops varieties, then dry-hopped with two other kinds, something that gave it a huge hoppy punch (for that era), but with a less bitter, more fruity feel. It was also unfiltered (meaning it was hazy, but not in the same way as today’s hazy IPAs). And because it was also moderate in alcohol, at 4.9 percent ABV, it really hit the sweet spot for drinkers. The experiment turned out to be one of the brewery’s bestsellers and continues to be a beer that’s renowned for shaking things up.

Yeti Imperial Stout

Great Divide Brewing

Yeti seems like it’s always been around — a trustworthy landmark that is used to set the standard. In truth, Yeti wasn’t created until 2003 (first as Maverick Imperial Stout), nine years after Great Divide was founded. Beer geeks loved it, but bars thought it was over the top, and it would take some time and a lot of education before they got used to what the company initially referred to as “an onslaught of the senses.” Gorgeous to look at with its deep black color and white head, and packed full of hops in addition to roasted malts, Yeti, at 9.5 percent ABV, ranked for years among the nation’s top beers on many lists, winning medals and accolades along the way. Although it is still a top seller, these days Yeti is often overshadowed by its cousins — an entire brand, in fact — of other Yetis, including Oak-Aged Yeti, Espresso Oak-Aged Yeti and more. It has also taken a back seat to other bigger, flashier stouts. But it is still the embodiment of an American imperial stout and a measuring stick by which other breweries measure their own creations.

Dale’s Pale Ale

Oskar Blues

Unapologetically bold and loaded with hops, Dale’s is sold as a pale ale, something that would shock beer lovers of the ’80s and ’90s. But “shock” has always been the name of the game for Longmont’s Oskar Blues, which was the first brewery to can craft beer in 2002 and is now part of the eighth-largest craft brewing company in the country. Recognizable nationwide for its red, white and bright-blue can, Dale’s is a defiant and “voluminously hopped mutha” of a hop bomb that was originally created to both satisfy the cravings of company founder Dale Katechis — who was always searching for the hoppiest beers he could find out of California — and to attract people to his original restaurant in Lyons. It worked on both fronts. Aside from Coors and Fat Tire, no beer oozes “Colorado” more than Dale’s.

Apricot Blonde

Dry Dock Brewing

Other beers from Dry Dock may have made this Aurora brewery popular with beer geeks, but it was Apricot Blonde that pushed it into the mainstream, becoming a staple in almost every liquor store and supermarket across the state. Easy to drink, perfectly balanced and approachable, Apricot Blonde, made with apricot purée, was first brewed in 2006, a year after Dry Dock opened, and it found a perfect happy spot in beer drinker’s mouths. At 5 percent ABV, it also inspired dozens of other lower-ABV fruited blondes.

Odell IPA

Odell Brewing

Odell IPA was, and continues to be, one of the finest IPAs this state has ever produced. But more than that, the award-winning standout has been the basis for a slew of other beers that used it as a model and a guide. Unveiled in 2007, Odell IPA itself was based on other hoppy beers of the time — not as an imitator, but as a way to brew something less bitter. And it changed the style so much that even Brewers Association founder Charlie Papazian admitted as much to the Fort Collins Coloradoan. “It was one of the first IPAs with the intention of elevating fruity aromas accessible in hops that is so common today,” he told the paper, “and it also kind of tempered the assertive bitterness that was out there.”

Oskar Blues managed to fit this enormous stout into tiny cans, starting in 2007.

Eddie Clark/Oskar Blues

Oskar Blues

No one was ready for Dale’s Pale Ale when it came out in a can. And no one was ready for a 10.5 percent Russian imperial stout in a can, either. But the brewery didn’t care, which is why the FIDY in Ten FIDY stands for Fuck Industry, Do It Yourself, according to some people. First released in 2007, this beer pours black and is often described as having a syrupy, “viscous” feel, like “motor oil,” that makes it a perfect cold-weather elixir. Some people have even aged Ten FIDY, another first for cans. Big, bruising and absolutely delicious, it is still a hard beer to beat — still on the cutting edge — even after twelve years on the market.

TPS Report

Trinity Brewing

One of the first beers in Colorado, if not the entire country, to be brewed entirely with “wild” Brettanomyces yeast, TPS Report was conceived of in 2008, shortly after Trinity Brewing opened in Colorado Springs. Using a wheat-beer base, Trinity founder Jason Yester added lemon and tangerine zest and aged the whole thing in French oak chardonnay barrels. The result was an earthy, elegant, complex beer that was like nothing most people had tasted before. The beer inspired a whole generation of brewers who came to prominence in the ensuing years, and 100 percent Brett beers are now much more common.

Modus Hoperandi

Ska Brewing

When Ska debuted Modus Hoperandi in 2009 — and in a can, no less — it was very different from the other IPAs around. Colorado was still mostly known for its pale ales, its raspberry wheats and its ambers. Modus, at 6.8 percent ABV, was closer to the famed IPAs from such California breweries as Stone, Sierra Nevada, Green Flash and Bear Republic. Brewed with Centennial, Cascade and Columbus — the mothers of American-style hop varieties — it came in at 88 IBUs, back when bitterness mattered, and it was certainly bitter. But Modus’s piney, resinous, grapefruit blast also finished with a slight sweetness that made it easier to drink, and its format made it much more portable. A decade later, the beer remains a staple for many people.

The 2010s

Milk Stout Nitro

Left Hand Brewing

Left Hand Brewing has made some true Colorado standard bearers since it was founded by Eric Wallace and Dick Doore back in 1993; they include early classics such as Sawtooth Ale, Maid Marion Berry and Jackman’s Pale. But the brewery turned the entire nation on its head in 2011 when it debuted Milk Stout Nitro. A revamped version of one of its oldest beers, Milk Stout, the beer was infused with nitrogen gas before being bottled so that it would pour like a classic English stout from the tap, with a cascade of bubbles, and have a rich and creamy mouthfeel. The beer was an instant hit, and quickly became the must-have for many bars and restaurants. It also became Left Hand’s best-selling product, completely reinventing the company and helping to grow both the brewery’s and the state’s profile.

Graham Cracker Porter

Denver Beer Co.

Graham Cracker Porter wasn’t supposed to stick around after it debuted during Denver Beer Co.’s opening week in 2011. Brewed with actual graham crackers, it had been designed as a fun one-off. But it created such a huge demand that DBC brewed it again and again, eventually canning the beer as its flagship. Evocative of s’mores with its chocolate malts, graham-cracker flavor and soft mouthfeel, it became emblematic of a new style of brewing that used non-traditional ingredients, and of a new breed of taproom-only breweries that changed Denver’s brewing scene dramatically over the next eight or nine years. Today, GCP gets its graham-crackery flavor from vanilla and biscuit malts, but the beer, in its distinctive brown can, continues to be a hit and a top seller around the state.

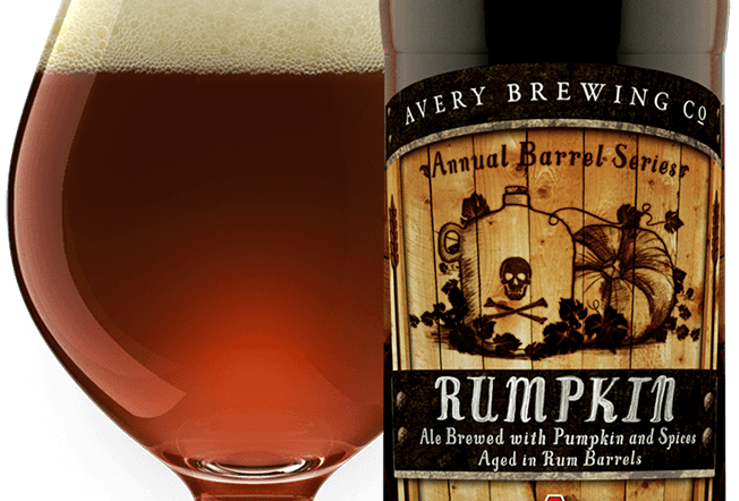

Rumpkin

Avery Brewing

“Kids wait for candy around Halloween. Adults — at least the big-beer-loving kind — well, they wait for Rumpkin, Avery Brewing’s tricky barrel-aged treat.” That’s what Westword wrote in 2011 when the Boulder brewery bottled its cult beer for the first time. Brewed with at least five spices and aged in rum barrels, Rumpkin clocked in at 16 percent ABV that year, higher than most wines, pushing the limits of many beer drinkers and taking Avery’s already outlandish reputation up another notch. Although barrel-aged beers certainly existed in 2011, Rumpkin broke new ground and paved the way for a now widespread culture of barrel aging that has become an art form all its own.

Persica

Crooked Stave Artisan Beer Project

When Crooked Stave moved from Fort Collins to Denver in 2012, Persica was one of the first beers it made here, and it was definitely the first to find a major following. A golden sour aged in oak barrels for months with “copious” amounts of fresh Colorado peaches, the beer made other breweries take notice as well. At the time, Crooked Stave was the only brewery that focused entirely on wood barrel-aged sour or wild ales, and it pioneered the combination of oak, Brettanomyces and large quantities of locally sourced fruit. Over the years, Crooked Stave has attracted attention from all over the world, but Persica remains one of its most-loved releases.

Breakfast Grapefruit IPA

Strange Craft Beer Company

Tim Myers has been behind many craft-brewing “firsts” in Colorado. He was the first person to open a taproom-only (no food, no packaging) brewery in Denver; the first to have to change its name because of a trademark (Strange Craft was formerly known as Strange Brewing); and the first of a new generation of brewers to step away from style purists. This willingness to forge a new path, along with his home-brewing roots, in 2012 led Myers and fellow brewer Harry Smith to explore how to make the most citrusy IPA possible, using only hops. After creating numerous iterations, they finally landed on the Amarillo and Citra hops version that would become Breakfast Grapefruit IPA once Myers added one gallon of grapefruit juice per 310 gallons of beer to give the beer a slightly drier finish with a little more grapefruit bitterness. A couple of years later, San Diego’s Ballast Point Brewing introduced Grapefruit Sculpin, a beer that sparked a national trend when it came to citrusy and fruited IPAs, not to mention the use of hops (some of them experimental) to mimic those flavors. Was Strange Craft the first? It’s hard to know, but as usual, Myers was changing the scene — behind the scenes.

Super Power IPA

Comrade Brewing

Boasting a wickedly fresh burst of new-school hops, Comrade’s Super Power IPA was one of the first West Coast-style hop bombs to incorporate more modern varieties such as Simcoe, Citra and Amarillo, as opposed to old standards like Cascade, Centennial and Chinook. But it was also the first IPA to gain a following without ever being packaged, and it would come to define the possibilities for the taproom-only breweries that had taken over the beer scene. Super Power still isn’t packaged, and it still attracts beer drinkers like crazy.

Codename: Superfan

Odd13 Brewing

This beer took the excitement that had been reserved primarily for sours and barrel-aged stouts, and transferred it to a brand-new kind of beer: hazy, “New England-style” IPAs. Cloudy, even murky, sweet rather than bitter, and made with newer hop varieties that impart tropical, juice-like flavors and aromas, Codename: Superfan and other beers of this type caught on quickly in Colorado and across the country. Odd13 experimented with various versions of the Codename: Superfan in its taproom before releasing it in cans — the brewery was the first in Colorado to release a canned hazy IPA — and announcing that it would replace its flagship bitter IPA with this new juicy one. Previously, the larger craft breweries in the state had set the tone when it came to innovation in brewing, including packaging, new styles and marketing. But Codename was the beginning of a Titanic shift in which the smaller breweries would take on that role, leaving the bigger breweries to play catch-up — something they have been doing ever since.

Juicy Bits

WeldWerks Brewing

No single beer style has changed the craft-brewing industry more quickly or more drastically than hazy, “New England-style” IPAs, and no Colorado beer has played a larger role in that change than Juicy Bits. One of the first — and still one of the very best — hazys in the state, the tropical, almost orange juice-like beer has little bitterness but tons of flavor, and people began clamoring for it as soon as it hit taps in 2016. So many people wanted it, in fact, that they beat a now well-worn path to Greeley to get it. The beer helped the brewery launch a new way of selling small-batch beers — in Crowlers and, later, in sixteen-ounce cans — and also of selling and marketing them.

Slow Pour Pils

Bierstadt Lagerhaus

When Denver was founded in the late 1850s, there was only one brewery and only one kind of beer: light-bodied German lager. Over the next few decades, pilsner, helles, Marzen and bock came to define “beer” for most people in Colorado and the rest of the country. After Prohibition, the breweries that survived chose to water these styles down and merge them together, eventually ending with the light industrial lager, a lowest-common-denominator beer that fills most liquor-store coolers today. When craft brewing became a force in the 1990s, lagers — especially pilsners — were looked down on because of this association, buried by an endless variety of fuller-flavored ales such as ambers, pale ales, IPAs and stouts. It wasn’t until the early 2010s that lagers started to make a comeback among craft breweries, and it wasn’t until Bierstadt Lagerhaus opened in 2016 that they actually became trendy. That’s because the brewers dedicated themselves to Old World tradition and brewing techniques, creating lagers that taste — and look — great. Nowadays, many Colorado brewers turn a deferential eye to Bierstadt when they bring up their own pilsners, but they have also been inspired to produce beers that stand proudly on their own.