They don't have any references because they've been living in Juan's mother's home, which they inherited, in the little southern Colorado town of Saguache, but they'll be glad to fill out everything else on the rental application. They've moved to Denver to be closer to Brenda's sick father, who is in a nearby hospital.

Brenda, a big woman with blond, braided pigtails, is 42. She'll charm you with her sweet smile. Juan, 57, is a short, round man with a dark ponytail. He's a little rough around the edges, but then, he's a Vietnam veteran.

Now you've met the Manchegos, and this is the last time you'll ever have a nice thought about them.

The initial sign of trouble comes after you hand over the keys to your rental property. Brenda will pay the first month's rent with hundred-dollar bills or a money order rather than a personal check, but she won't have quite enough for the security deposit. Her husband's disability check from the VA was late again, she'll tell you. She's sure it will arrive soon.

Then things start to get really weird.

David Stone knows this story. He knows the Manchegos all too well.

David and his wife, Andrea, moved to Denver four years ago from Bishop, California, a small town where David was raised and owns two rental properties. "That's why I'm naive," he says. "A credit check is nonexistent there." In Bishop, David relies on his father, who knows everyone in town, for references on potential renters.

Since his dad doesn't know anyone in Denver, David decided to invest in a nice property here so that he'd only have to deal with the sort of people who could afford a monthly rent of $1,500. "I didn't want to be a slumlord," he says. In August last year, he bought a 1927 brick bungalow at 680 Cherry Street for $308,000 and then spent several thousand dollars more to renovate the bathroom, paint and do minor repairs.

A few months later, Brenda Manchego saw the "For Rent" sign in the yard and called the Stones. "She said her husband is an ex-Marine who needs back surgery, which is why they need to be close to the hospital," David says. "She said they didn't have any references because they'd owned a house in a small town somewhere in southern Colorado, but that they were in Denver because her dad was in the hospital and they wanted to be close to him, too.

"It was a fairly tight story," he adds.

Brenda agreed to pay $750, a half-month's rent, so that she could move in on November 15, plus the last month's rent of $1,500. "The first day, she was a hundred bucks short and she didn't have the last month's rent," David remembers. "And they paid in cash, which is a little strange... She's a really nice lady, though, I'll say that for her."

So the Stones had Brenda sign an agreement stating that she would pay $3,000 on December 1 to cover the last month's rent plus December's. On December 3, the money finally arrived, but for only half the agreed-upon total. And instead of mailing a check, the Manchegos waited in their car while their youngest son rang the doorbell of the Stones' home in Washington Park and hand-delivered a money order. It was "creepy," David says.

The Stones repeatedly called the Manchegos to let them know they still owed $1,500 and finally resorted to a letter delivered to the rental home on December 5. "It is not our intent to resort to legal matters in this affair," the letter stated. "However, if the matter is not resolved by Dec. 10, 2001, we will begin legal proceedings to repossess our property and pursue an eviction.... We would also like to further reiterate that, as stated in the lease, rent is to be paid at [the Stones' P.O. box]. It does not follow the terms of the Lease that rent be hand delivered to our residence, and is a violation of our privacy."

When no money arrived at either location, David offered to let the Manchegos pay the remaining balance in installments. But the Manchegos declined, telling him they would just move out by the end of December. "That's how they bought two extra weeks," he says, because as January approached, the Manchegos decided they wanted to go to court instead.

Their demeanor had changed, too. Gone were the smiling couple from southern Colorado. "They were calling me a slumlord, saying the house was in such a poor state of repair," David recalls. "They said there were mice; they claimed the upstairs tub and shower were leaking and that the downstairs was moldy, which is why they shouldn't have to pay rent."

When David went over to the house with an exterminator -- who told him there were no mice, he says -- he was shocked. "There were piles of junk everywhere. It looked like they hadn't unpacked anything. There was a four-foot-high pile of laundry."

After that, David began driving by the house on his way to work. "I saw people I'd never seen before leaving the house early in the morning and getting into cars," he recalls. "I started to get the feeling that there was a whole tribe living there."

At the end of December, David posted a standard eviction notice on the door of the house, giving the Manchegos three days to vacate the premises. Since these notices carry no legal weight by themselves, he then appeared before a Denver County Court judge to prove that he had posted the notice; he asked that the Manchegos be forced to pay the $1,500 plus court fees. As required by the court, David subsequently posted another notice on their door, along with an answer form giving the Manchegos a chance to explain themselves to a judge.

Brenda Manchego filed her answer with the court on January 4, writing only that "I Brenda Manchego never agreed to $1,500 last month rent." A hearing was set for January 11, adding to the time the family could live in the house rent-free.

"That's what tipped me off that they had done this before," David says. "They knew just how to work the system. They knew the system better than I did. Everything they did was done to elongate the process."

On the day of the hearing, Brenda called the county court offices to say that everyone in her family had strep throat and asked for a postponement. But the judge went ahead and ruled in the Stones' favor, awarding them a judgment for the lost rent; he also gave the Manchegos until January 21 to move out.

To ensure that they vacated the premises, David had to pay $180 to the City and County of Denver to have a sheriff's deputy physically take back the property. When that deputy arrived on January 21, the Manchegos were already gone. They'd left behind a few presents, though, including a refrigerator filled with rotting food, a broken faucet that cost $900 to fix and a house so dirty that David had to have it professionally cleaned.

The Manchegos have never paid the money they owe, but David still thinks he was relatively lucky. "Now I use a service to get a credit history on people," he says. "I consider it a fairly inexpensive lesson learned."

Over the past two decades, dozens of landlords in the Congress Park, Hale and Montclair neighborhoods, where rents currently range from $1,000 to $1,800 a month, have been taught similar lessons by the Manchegos.

Most of these landlords were told the same story. They heard about the house in southern Colorado, the military pension, the sick father. None of them checked out the story.

Like Stone, many wound up taking the Manchegos to court. And also like Stone, none of them has ever seen a dime.

Over the last twenty years, the Manchegos have lived in more than thirty rental homes in Denver. At least seventeen former landlords -- most of whom own houses within blocks of each other -- have sued the couple in Denver County Court, trying to evict them and reclaim a total of over $24,000 in lost rent, deposits and late fees. Many more have simply swallowed their losses in exchange for never having to deal with the family again.

A lesson learned.

But evictions and rental disputes aren't the only legal problems the Manchegos have stacked up like pancakes.

Robin McLean, who lives in the Montclair neighborhood, was never the Manchegos' landlord. She got involved with them in 1995, when she began taking her daughter to a woman named Brenda Bellis, who provided daycare in her home at 118 South Ivy Street.

After a few months, McLean started to suspect that Brenda was leaving the children -- most of them under age two -- at that home alone. And things got stranger in August, when Brenda moved out of the Ivy Street house during the middle of the night and didn't call McLean until a few days later to give her a new address.

Around this time, McLean's daughter developed an almost hysterical aversion to baths and hairbrushes. McLean wondered if Brenda was using them to discipline the children in her care.

"One day I came to pick her up and she was ballistic," McLean says. "Her hair was all wet, and Brenda said she'd just given her a bath. The next day, I called a friend of mine who was a cop and asked him to do a background check on Brenda. He called me back later and said, 'Go pick your daughter up right now and don't ever take her back there. Go get her, and we'll talk when she's safe.'"

After talking again with her cop friend, McLean spent many hours at the Colorado Department of Human Services, which inspects and licenses child-care providers and keeps records available for public viewing. She read complaint after complaint about Brenda Bellis, which turned out to be one of several names used by Brenda Manchego over the years. (Bellis is her maiden name.)

Brenda repeatedly had been accused of providing child care without a license or telling people she was licensed when she was not; of lying to her many landlords about whether she was doing daycare; and of taking deposits from parents whose children she already cared for or from prospective clients -- and then skipping out on them by moving to another house.

On this last claim alone, Brenda had been sued at least seven times in Denver County Court by people demanding a total of over $4,100 in down payments that were never returned.

In September 1992, for instance, Blaine Stokes and his wife, Phyllis MacCartney, sued Brenda, claiming they'd given her a down payment of $340 in May of that year to begin taking care of their young daughter in August. But when August came, Brenda demanded another $340 -- at which point Stokes and MacCartney decided to find another provider. Brenda offered to return the down payment, according to the lawsuit, but she never followed through.

Much more troubling to McLean was what she learned about Brenda's own family. The files, which took McLean several days to get through, include accusations of neglect against both Brenda and Juan Manchego, as well as arrests for domestic violence and two aborted divorces.

"From what I read, this woman shouldn't have even had custody of her own kids, let alone be able to watch other people's children," McLean says. "I don't know how she continued to get licensed over the years. This is someone who has fallen between the cracks."

Although Brenda hasn't been issued a daycare license since 1995, many of her more recent landlords report seeing multiple cribs and car seats in their homes and say they've witnessed people coming and going in the mornings and evenings.

David Stone doesn't know whether Brenda was running a daycare operation out of his house -- he suspects she was -- and he doesn't much care. He's just happy that he'll never have to see the Manchegos again.

Juan and Brenda Manchego didn't leave a forwarding address when they moved out of Stone's house, but the mailman found them anyway.

"I got a call from my mail carrier," says Franz Garsombke, a Golden software engineer who'd just rented a two-bedroom, one-bath home at 970 Grape Street to a nice couple from southern Colorado. "He said my new tenants had lived in at least three houses on his route in the last six months. He said he felt sorry for them the first time they got evicted, but that he has tracked them since. Well, I got the addresses and I did some legwork, and I talked to three landlords."

What Garsombke learned from these landlords -- Russell Casement, Lucia Aandahl and Ron Ranieri -- gave him an idea of how hellish the next few months would become.

"They said they'd just moved up from southern Colorado," remembers Casement, a dentist whose mother, Birdie Casement, rented her house at 770 Glencoe Street to the Manchegos in August 2000. "They told her how perfect it was and how excited they were to move in.... These people are professionals.

"My mother built that house back in 1937, and she lived in it for most of that time," he adds. "Since she started renting it, she'd never had any problems until this. She's 87 now, and these people took advantage of her."

When the Manchegos failed to pay their September rent and began complaining about faulty plumbing, Casement posted an eviction notice on the door and then took them to court, asking the judge for $3,900 for two months' rent and a security deposit. The Manchegos took their time filing an answer. On September 12, Juan, going by the name John, finally submitted the paperwork, along with a counterclaim of $2,500. "Work on the house, plumbing, electricity, is not being done," he wrote. "Payment for rent of property was refused."

Casement denies that he ever refused a rent payment. The house didn't have plumbing problems before the Manchegos moved in, he says. Like the Stones, he believes the family did the damage themselves -- on purpose.

The judge ruled in Casement's favor and ordered the Manchegos evicted. By October 7, when they moved out in the middle of the night, they'd lived there rent-free for more than a month -- time to do plenty of damage.

"They'd stuffed meat in the attic and under the stairs in the basement," Casement says. "We had to get professional cleaners in there to find out where the odors where coming from. That cost me another couple grand. The telephone cables were cut, and there was so much trash in the back yard that it took two truckloads to get it out. When they left the house, they left all the faucets running and all the windows open, and it was snowing that night. They're real clever at damaging houses. It's just disgusting what they do. They are real vultures."

Although Casement was awarded a settlement, the court was never able to find the Manchegos to serve them with the order to pay.

But they hadn't gone far.

Lucia Aandahl has been renting out a small, well-kept house at 1220 Jasmine Street for more than fifteen years; it's next door to her own home, and she'd never had a problem renter. Not until the Manchegos showed up on September 8, 2000.

"I had become trusting over all that time," says Aandahl, a retired Denver Public Schools principal who owns two rental properties. "They were very jovial when they first came. Juan said he was a 100 percent disabled veteran and that they had just sold their house in Saguache, somewhere down in southern Colorado. That's why they didn't fill out the references section of the rental application.... They said they didn't have enough for the security deposit, though, so I told them that was okay, they could pay it off over six months. They paid the first part with hundred-dollar bills, always cash.

"But after they moved in, they immediately told me the house was full of mice," Aandahl remembers. "Nobody before had ever complained of mice. So Juan and I bought ten traps. Then they started complaining that the house was filthy."

The Manchegos paid their October rent but told Aandahl they couldn't make that month's down-payment installment because Juan's disability check had been lost in the mail. Then they started to complain about the bathroom, saying the plumbing wasn't working right. "In November, they decided they could only pay half the rent," she recalls, "and in December, they didn't pay any rent at all."

So Aandahl posted an eviction notice on the door and sued the couple for $1,083. Brenda filed the Manchegos' answer with the court on December 8, claiming that she'd tried to pay the rent but that Aandahl had refused to accept it.

At a hearing in late December, Juan showed up using a cane and "moving his eyes around as if he had some kind of a tic," Aandahl says. "He told the judge he'd just had a stroke, but the next day, I saw him walking very well. One of my neighbors later saw him carrying furniture."

Although the Manchegos lost the case, no one from the Denver County Sheriff's Department was available to evict the family until after the New Year.

"I guess the lesson is that I should do my homework," Aandahl says. "Now I have a very tight contract where everything is spelled out, and I charge $20 if I want to do a background check. Everyone has to give me telephone numbers and driver's-license numbers and Social Security numbers."

The Manchegos' paper trail picks up two months later, in March 2001, when they rented a house at 930 Grape Street owned by Ron Ranieri, a RE/MAX real-estate agent who owns and rents properties on the side. Ranieri is one of a few real-estate professionals who have had run-ins with the Manchegos; most of the other landlords who've sued them own only one or two other properties, often a house that has been in the family for years.

"It hadn't been in the paper more than one day when [Juan] shows up at the house," says Ranieri, who owns eleven rental properties around Denver. "I didn't hear him knock, but the door was open, so he just came inside and tracked me down. He said he'd just moved up from southern Colorado and that his mom was sick. I felt bad for him. He had the smoothest handshake, he was the nicest guy -- and just like that, he said he wanted it. Usually guys have to ask their wives or think about it, but not him. He came back in half an hour with half the deposit. I said he needed it all, so he left and came back with the whole thing. He said, 'I'm a veteran, and my word is as good as gold.' I believed him. Normally I do background checks, but it was March, it was cold, and I had two screaming kids at home. I guess I was a sucker."

Ranieri's first clue that things weren't right came when the Manchegos didn't put the water bill in their name; when they finally did switch it over, they used the name of one of their daughters. "Then, my guy who does all my repairs told me that their blinds are never opened, they are always at home, they never talk to anyone, and they got people coming and going from the house all the time," he remembers. (Aandahl says that her neighbors told her the same thing.)

The Manchegos soon began complaining about a leaky upstairs bathtub and a broken disposal, threatening to withhold the rent money. Ranieri took them to court, asking for their eviction and $1,465. "They tried to countersue me," he says. "Somehow, they got the upstairs tub to leak and they told the judge it had leaked through the ceiling. They had pictures. Well, I know what a water leak looks like, and this wasn't it. I think they got it wet and then knocked through the drywall with a hammer. They told the judge, 'See, he doesn't take care of his properties.'"

Juan showed up in court on crutches. "The judge wouldn't let the previous landlords talk," Ranieri says. (The mailman had put him in touch with Aandahl and Casement.) "I really thought I was going to lose. The nerve of these people. They aren't afraid of anyone."

He didn't lose, but before a judgment could be ordered against the Manchegos, they'd fled once again.

"I've been screwed before, but never like these people did it," Ranieri says. "I learned a lot from this experience, and unfortunately, it's that I shouldn't trust people."

Ranieri's Grape Street property is just a few doors down from the house the Manchegos rented from Garsombke. Talking to Ranieri and other former landlords, Garsombke realized how tough it might be to get rid of the Manchegos. He also learned that the police and the courts wouldn't be much help.

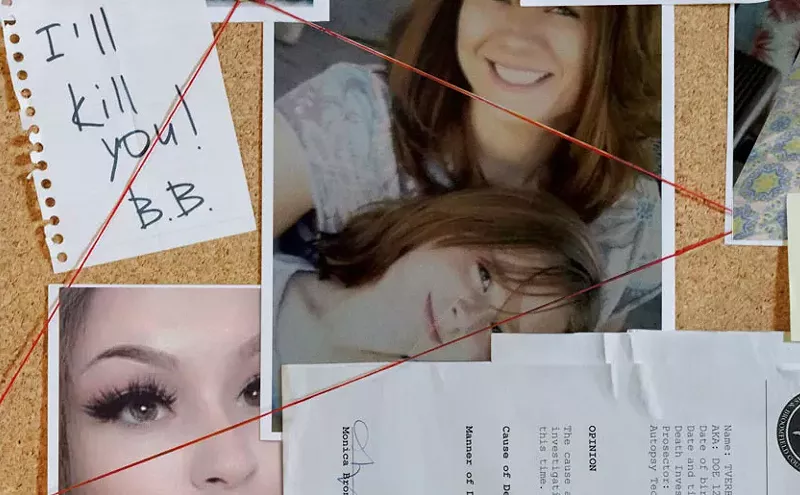

When Casement discovered the damage the Manchegos had done to his home, he called the Denver Police Department and filed a report. "Extensive damage was done to the house, rotting food was left in the heat ducts, garbage was left in the basement, cables had been cut, cupboards and shelves were trashed, eggs had been left behind the stove...telephones were stolen along with miscellaneous garden tools," that report reads.

But the cops didn't do much more than take the report. "They just told me I should have checked their references better," Casement says. "I called numerous times and spoke to a Detective Ron Vigil, and to his supervisor, but he didn't want to do anything about it. He said it was civil, not criminal. But I fail to see how it is not criminal."

DPD spokesman John White confirms that Vigil told Casement the matter was a civil one. (Vigil would not comment for this story.) "This case was refused by the district attorney's intake office," White says. "We can't pursue any case beyond the DA. The DAs are the experts in this. I can't comment on the decisions that they make."

Since Casement first spoke with Vigil, Aandahl, Ranieri and Garsombke have all talked with the police officer, to similar effect.

Brenda Manchego insists that she and her husband are the real victims. She says that landlords in Colorado are interested only in money and that they will say or do anything to take advantage of people like herself.

Like the police, she thinks the disgruntled landlords should have checked her references. "It's interesting that these landlords don't protect themselves better, that they just want their money," she says.

None of her recent landlords -- not Garsombke, not Stone, not Ranieri, not Aandahl, not Casement -- asked to see her references. And they were unclear about terms, she adds: "Stone, I told him when we rented the place, 'You never said anything about a last month's rent,' and he said, 'Well, maybe it was some kind of confusion.' I said, 'It's not in the lease, and we never discussed it.'"

(Stone provided the court with two documents that dispute Brenda's contention; both include an agreement to pay the last month's rent, and both are signed by Brenda.)

"And Franz, I remember his girlfriend or fiancée saying, 'Oh, good -- cash.' All they wanted was their money," Brenda continues. "When we moved into Birdie Casement's place, it was a disaster. Lucia's was barely fit for living in, and Franz's place looks like shit. But in our position, we can't afford to be too picky. We accept these places because of financial reasons. Whether you believe it or not, we are victims here, too."

Brenda denies that she has ever used fake information on a lease agreement or used fake information to secure an account with a utility company. But court documents indicate that she has repeatedly transposed digits in her Social Security number, provided a fake history and offered fake references. And Juan has supplied a fake military-service ID number on at least one occasion.

After the Manchegos moved out of assorted houses, their former landlords were contacted by fraud investigators for both Qwest (or its predecessor, US West) and Excel Energy (or its predecessor, Public Service Company of Colorado). The utility bills had been put in the names of some of Brenda and Juan's six -- not three, as Brenda had told some of her landlords -- children, the investigators said, and the children's Social Security numbers had been used, too.

After abandoning Ranieri's place, the Manchegos next turned up at 118 South Ivy Street, in a rental owned by Hope and Daniel Hernandez.

"They said he had been in the Marines and that he got a check every month," Hope Hernandez says. "But they just paid one month's rent, and that was it."

The Hernandezes managed to evict them quickly. "There was no damage, but they left it really, really dirty," Hope says. "I had to paint it after they left, and I had just painted it two months earlier."

More shocking than the condition of the house, though, was Hope's discovery that this wasn't the first time the Manchegos had lived at that address.

Six years earlier, in April 1995, the previous owner of the house, Galen Aki, had also rented it to the Manchegos.

Aki remembers the couple as clearly as their more recent landlords do. "The husband and wife know how to use the system," he says. "When you meet them, they are pinnacles of the church and everything else. But that changes."

Aki was able to evict the Manchegos in August that year after they stopped paying rent, but the damage to the house was overwhelming. "It was literally destroyed," he remembers. "There were holes in the ceiling of the kitchen for no apparent reason, and holes in every wall. The carpet was destroyed, and they left tons of trash."

Although he knew that Brenda had been operating a daycare facility out of the home -- on April 21, 1995, she'd received a license allowing her to take in four children at a time at 118 South Ivy -- he had no idea that Brenda was ripping off her clients and had been accused of neglecting the children in her care.

He learned that later from Robin McLean.

In late 1994, McLean was looking for a daycare provider for her daughter when she met Donna Austin, who'd been doing daycare in her home at 5211 East Eighth Avenue for several years. After checking into Austin's background with "a fine-tooth comb" and finding no problem, McLean signed up.

But six months later, Austin told McLean that she wouldn't be providing daycare for a while. She said she had three sisters who provided similar services out of their homes, McLean recalls; one, Brenda Bellis, even lived nearby.

"I felt comfortable leaving my child with Donna," McLean says. "And when you have one family member who you think is okay, you think the next one will be, too." McLean met Bellis and "it seemed like comfortable fit," she remembers. So without checking her background, she signed up with Brenda.

One day that summer, when McLean was in the neighborhood during working hours, she decided to stop by Brenda's house. "No one answered the door; no one was around," she says. "I didn't know where they could have gone. All she had was a pickup truck and six babies, half of whom weren't walking yet."

McLean ran home and called Brenda's number but reached the answering machine. "I was getting ready to call the police when she called me back," McLean says. Brenda told her she'd used a wagon to take the kids to a nearby park.

A few weeks later, McLean again stopped by 118 South Ivy. No one answered the door -- but this time, McLean says, she could hear babies crying. She immediately went home and called the police. When she got back to the house, she found Brenda and the police. "I told them what I'd seen and heard, and she told them that she had been at the park with the babies again," McLean says. "I told her she was lying, but it was her word against mine."

Still, McLean kept taking her daughter there -- her husband at the time thought Brenda was wonderful, she explains. But then Brenda abruptly moved out of 118 South Ivy and into a house at 800 Forest Street, next door to her sister Donna's place.

That's when McLean finally pulled her daughter out of Brenda's care and went to the CDHS to read Brenda's file. After that, McLean did some research of her own and started compiling more files. She learned enough about the Manchegos that she became determined to see that Brenda would never offer daycare again.

Here is what McLean learned. According to court records, the Manchegos began living together in 1978, the same year that their first daughter, Quoreen, was born. At the time, Juan had already been married twice and Brenda had another daughter, Roni, who was born in July 1976.

In December 1981, the two broke up and began a bitter custody battle for Quoreen. But three months later, they reconciled and asked that the case be dismissed.

In November 1982, their second child, Juania, was born; in May 1985, their first son, Juaquin, was born.

In July that year, the family moved into a house at 1175 Cook Street that was close to where Brenda's mother, Ruth Bellis Chacon, lived in the 1200 block of Milwaukee Street. Brenda applied for her first daycare license. A few months later, in October 1985, she was granted a six-month provisional license at another address, 1018 Jackson Street.

Juan and Brenda were officially married on June 6, 1986. Their fourth child, Meagan, was born in July 1987.

The Manchegos bounced from address to address in the same neighborhood. In July 1988, they landed at 520 Monroe Street, where Brenda got licensed for a full year.

The first complaint appeared in Brenda's CDHS file in February 1990. It was submitted by Barbara Cusick, who owned a house at 674 Albion Street, where the Manchegos were living. Cusick reported that Brenda had been providing daycare in violation of her lease agreement. In addition, Brenda hadn't bothered to get licensed at that address.

Later that month, Roni Bellis, then thirteen, ran away from home and told social-services workers that her mother had been forcing her to take care of daycare children instead of going to school, according to CDHS documents; Roni said she wanted to live with Chacon, her maternal grandmother.

In March 1990, Juan asked for and received a temporary restraining order against Brenda's mother, who over the phone had threatened to do him bodily harm, he claimed. (Chacon, a daycare provider herself for almost thirty years, died in June 2001.)

In September 1990, Juan filed a report with the CDHS accusing Brenda of leaving her daycare children alone while she ran to the store, keeping them in the basement, strapping them into their car seats all day, and leaving them with her fourteen-year-old daughter and instructing her daughter to "take the children out the back" if anyone knocked on the front door. But Juan went back to the department the next month and recanted his story, saying he had simply been mad at Brenda for making "accusations" about him.

Other people had plenty to say about Brenda, though, and her file got thicker. On October 11, 1990, one woman complained to the CDHS that she'd given Brenda $650 as a down payment on child-care services. She decided not to go with Brenda, then learned that her check had already been cashed. She also claimed to have been harassed by Brenda's daughter.

That complaint listed Brenda's address as 558 Columbine Street, where she had never been licensed, and it prompted the CDHS to send Brenda one of many reprimands for providing child care without a license. According to state law, providers can only be licensed at specific addresses; if the provider moves, she must get licensed again.

Through all of this, the Manchegos continued to have kids: Cory in December 1990, and Desiree in December 1991.

Brenda was arrested twice, in April and August 1991, and charged with multiple counts of domestic violence. Those cases were later dismissed.

She also collected a series of CDHS complaints involving her activities at other addresses, including 445 Albion, 701 Clermont and 795 Fairfax streets. (The Manchegos were evicted from the Fairfax house and sued by their landlord.)

On July 2, 1992, Juan filed for divorce and asked for custody of all six children, the house, the car and child support. In court documents, he claimed that he'd broken his back during the Vietnam War and had been receiving a disability paycheck from the Department of Veterans Affairs ever since. Despite his injuries, he insisted he would be a fit and able parent.

At the same time, Juan asked for a temporary restraining order against Brenda, alleging that within the past two weeks, she had "shoved, pushed, kicked, slapped and otherwise assaulted" him. "This could have severely damaged the current back condition [Juan] is suffering from," his lawyer wrote in the divorce filing. "Continued assaults could cause paralysis."

A month later, Juan and Brenda mutually agreed to halt the divorce proceedings. (Juan's lawyer, Jeffrey Edelman, later sued Juan for payment of legal fees totaling $1,570.52.)

Although McLean -- and many others -- don't believe that Juan really served in the military, the U.S. Marine Corps does have a record of a John Manchego with Juan's date of birth. The Marines would not release any information about dates of service or injuries, but Veterans Affairs confirms that a John Manchego receives a monthly payment of $3,011 at a post-office box in Denver.

According to Dean Tayloe, a spokesman for the VA in Colorado, veterans who have been 100 percent disabled qualify for the usual maximum of $2,163. "Additional allowances are payable for dependents, for certain severe conditions or for severe back or psychiatric problems," he adds. (The fact that the VA apparently classified Juan as 100 percent disabled comes as a surprise to the many people who have seen him load furniture onto his truck in the middle of the night.)

None of Juan's family members, many of whom live in Denver, responded to Westword's request for an interview.

In October 1992, Brenda was granted a six-month provisional daycare license for 315 Eudora Street. That house is owned by Susanna Russo, who eventually evicted the Manchegos and sued them for $1,300. (Russo didn't return phone calls from Westword.)

While the Manchegos were living at this address, the CDHS began its own investigation of the family. "After review of Brenda Bellis's social services file and information received, I cannot recommend a license and will ask the state to decide," one CDHS official reported in 1993. Around the same time, the department acquired a printout of both Brenda's and Juan's arrest records. (Juan had been arrested and charged with trespassing during the course of the Manchegos' first divorce attempt.)

Nevertheless, in late 1993, a CDHS worker recommended that Brenda be allowed to offer daycare out of her latest home at 741 Niagara Street. And she was subsequently issued a license for a new address after she moved into Galen Aki's house at 118 South Ivy, where she eventually met McLean.

As McLean continued to collect information on the Manchegos, she started contacting Brenda's clients and landlords, as well as the Denver District Attorney's Office and CDHS officials, telling them what she had discovered.

"I was just furious that this had been going on for as long as it had," says McLean. "It goes on and on, and it never stops. She just continues to get licensed. This is a travesty to our community." McLean grew so concerned about how the state handles daycare licensing that she ran for the Colorado Legislature in 2000.

Brenda accuses McLean of stalking her.

"Each one of my parents who pulled up to my house, Robin McLean, she told them that I had been charged with child abuse and that my kids were in foster care, which isn't true," Brenda says. "She made a lot of stories up. You know how parents can request the files of their providers -- well, I think providers should be able to request the files for parents.

"Yes, there have been some money issues, but none of them have anything to do with my children," she adds. "None of that information that she accused me of is proven, and none has any substance to it."

The Manchegos had a few rough months following their eviction from Aki's house. A prospective client complained to the CDHS that Brenda was providing unlicensed daycare at 800 Forest Street. This complaint led to criminal charges against Brenda, and in October 1995, she was fined $500 and given a year's probation -- during which time she was not allowed to provide child care.

That same month, David Cohen, the owner of the house at 800 Forest, evicted the Manchegos and sued them for $740. Although Cohen says he won't discuss the couple for fear of retribution, he does say that he never had a problem with Donna Austin, Brenda's sister, who was his tenant at 5211 East Eighth for thirteen years. He sold the house in 1998; she still lives there. "Donna ran a really nice child-care facility for a long time," he says. "She is hardworking and industrious and a lovely person." (While the Manchegos were living in Cohen's house, Juan filed for divorce a second time; that case was dismissed in February 1996.)

The Manchegos moved to 645 Hudson Street, a home owned by California resident Carol Burwell. Brenda was still on probation and prohibited from providing child care, but the CDHS started getting complaints from people who said they were clients of hers at the Hudson Street address. The parents, whose names have been redacted from the CDHS file, accused Brenda of everything from not letting them enter the house to leaving her charges unsupervised, having twelve children at a time in her care, and keeping down payments even after a parent decided to look elsewhere for child care.

Burwell, who didn't return repeated phone calls from Westword, evicted the Manchegos in January 1996 and sued them for $1,023 in lost rent and other fees.

The Manchegos next moved to 6203 East 11th Avenue, where they stayed for an unprecedented two years. On February 1, 1996, Brenda started her quest to get relicensed with the CDHS.

As part of that effort, she denied that she had taken deposits from parents after 1994 at times when she wasn't licensed, or that she had told people she was licensed when she was not. "As you know," she wrote in a May 6, 1996, letter to Dana Andrews, licensing administrator for the CDHS, "this evaluation was precipitated by a disgruntled parent, Robin McLean, who has made numerous unfounded and libelous statements to your office, my landlords and to current and former parents for whom I have provided child care."

But the CDHS had heard from many people other than McLean and denied Brenda's licensing request on May 15. "You have repeatedly provided unlicensed child care, which constitutes a deliberate violation of the Child Care Act," begins a letter from Andrews. "You have provided false or misleading statements to this Department during our review of your application in violation of [the Child Care Act]. Specifically, you failed to disclose at least two children whom you provided care for between October and November 1995; you failed to disclose that you have represented yourself to be a licensed child care provider when you were not; you failed to disclose that on more than one occasion since May 1, 1993, you failed to return child care deposits to families who were legitimately entitled to refunds.

"For the following reasons, we do not believe you are competent. Between 1989 and the present you have been sued by at least seven families for failing to return child care deposits. Other families are also owed deposits, but have not sued. Since 1989, you have been sued by at least seven landlords for failure to pay rent. Other landlords have also evicted you for failure to pay rent without filing suit. Several of the evictions were also based on your operation of a child care facility in violation of your lease. You have repeatedly represented to parents that you were a licensed child care provider when you were not. Of the above-referenced lawsuits, several have resulted in judgements against you."

Brenda appealed the decision. "Neither you or the child care licensing department showed any consideration for me or for my family and the hardships we had to incur because of this process," she wrote Andrews on June 8, 1996. She also complained that her privacy, and that of her daughters, had been violated because the CDHS had included medical histories of her children in its file, along with information about some of her clients.

In September 1997, Brenda's probation -- which had expired -- was revoked retroactively, and she was given another year's worth of probation because of the complaints regarding her daycare operation on Hudson Street.

But two months later, as the correspondence between Brenda and the CDHS continued, Andrews expressed a willingness to give Brenda a "12-month probationary license" provided she agree to twelve stipulations, including the following: She had to supply written permission from her landlord, agree to unannounced inspections, notify the department of any court action brought against her and notify the department if she fell behind in her rent payment.

But Brenda didn't follow up with the CDHS. "I could have if I'd wanted to, but I chose not to," she says. "There wasn't anything that said I couldn't do daycare again."

Brenda currently looks after her own two youngest children, her grandchildren and the children of a longtime client; under the law, she can care for children from one family that is not related to her without getting a license. "Right now I have a family that has been with me for twelve years and have been very happy all of that time," she says.

According to Andrews, under Colorado law, anyone who meets state regulations has the right to a child-care license, and as far as she can tell, Brenda has usually met those regulations. "What Ms. Bellis is doing, which would be considered a scam by the people who have complained about it, are not licensing violations," Andrews says. "And the money piece is a business deal between the child-care provider and the parent.

"People have the right to correct violations," she adds. "There isn't any number of specific chances that someone can get. If they meet the requirements, then we will license them."

In December 1997, a month after Brenda's final contact with Andrews, the Manchegos moved out of 6203 East 11th -- much to the owner's relief.

The owner of that house, who asked that her name not be used because she's afraid the Manchegos might retaliate, says that even though the family "skated" on her, she chose not to go after them in court because she never wanted to see them again. "That was probably the worst two years of my life," she says. "They come in with such big lies regarding their past."

The Manchegos would promise rent money for weeks and then pay only part of what they owed, along with late fees, saying they'd pay the rest later. "We played this game for two years," the former landlord says.

When she was finally able to force the couple out, it cost her more than $5,000 to put the house back together. "This was my mom's home, and they ruined the carpet, the flooring and the windows," she remembers. "[Juan] had the nerve to draw on one wall a life-sized picture of his dumpy old pickup truck. It wasn't removable. I can't tell you how many things they ruined. I was so angry. I wanted to belt them. I hate them."

In January 1998, the former landlord was contacted by investigators from both US West and Public Service Company, which were looking for Brenda and Juan. The companies told the woman that Brenda had been using her middle name, Renay, and her maiden name rather than her married name on accounts. (Records show that the Manchegos have had as many phone numbers as they've had addresses.)

The Manchegos next turned up -- in court files, at least -- more than a year later, in March 1999, in a home owned by Ward Wagner at 778 Glencoe. Although Wagner declined to comment for this story, his run-in with the family involved more than $3,400, two lawsuits and a countersuit.

From there, the Manchegos moved just two doors away -- to Casement's house. Four addresses later, they landed at Franz Garsombke's house at 970 Grape.

"This was the first time I'd ever rented out a house," Garsombke says. "Unfortunately, I picked the worst renters in the state."

Although Garsombke found out about the Manchegos' history shortly after they moved in, so far he hasn't been able to legally evict them. As long as they continue to pay their rent on time, the law says, they can remain where they are. "Everything on the rental application is false, but nothing in my lease says that is in violation," Garsombke says. "They told me they have two kids. They said they wanted to be there for two years, that they love garden work, that they'd fix up the house. They feed you everything you want to hear. They said they'd lived at Camp Pendleton in San Diego for thirty years and in Southern Colorado for two years. They offered to buy the furniture."

Garsombke has entered the house several times - each time giving the Manchegos 24-hour notice, as required by law -- and was disgusted by what he saw. "It was like I had entered a flea market; it was creepy," he says. He's taken numerous photos and recorded videotape of the home's interior. He's told the Manchegos that he knows about their past and will be watching them very carefully.

At one point, he even offered to pay them to move out.

The most recent time he asked to enter the house, the Manchegos declined to give permission. On May 21, Garsombke posted a three-day compliance notice on the door. After several delays in the court proceedings, on June 24 a judge recommended that in order to break the lease, Garsombke agree to let the couple live in his house rent-free for a month and a half; in return, the Manchegos have offered to move out by August 15. Both sides have signed off on the deal, but animosity still exists.

Brenda insists that Garsombke is simply out for money.

"When we moved into Franz's place, you have every good intention that you are going to take care of it, and you hope to be left alone and left to your own business," she says. "But we haven't been, and I've become very discouraged and upset. With Franz, we have done absolutely nothing. He feels like he has us in this position that we have this terrible background and he will do anything to get what he wants."

In January, she says, Garsombke told them that he'd been laid off and would need his house back. "But our lease is good until January 2003, and we said, sorry, we couldn't just up and move. Our kids are in school, and we have incurred financial expenses. And he said, 'That's too bad for you.' Then he told us a little birdie had told him we'd been evicted before. And I said, 'That isn't any of your concern. We have not broken the lease, and we are not doing anything wrong.' This is just a form of harassment.

"There are a lot of slumlords here in Colorado, and they say they will do this and that, and they don't," Brenda continues. "But we've learned that if we have to call the police so they can document something, that's what we will do. I'm not saying we are perfect, because we aren't. No one in this world is perfect.

"Maybe if Franz had done his job, had asked some questions, had asked for references and checked Social Security numbers, we wouldn't be there. Now he's just mad."

That's for sure. "They don't understand what is right or wrong," Garsombke says. "They take normal people to places they never think they would go in terms of revenge and justice."

For his part, Garsombke would like to make sure that the Manchegos can never again rent a home in his neighborhood -- or anywhere else. Although he hasn't had any luck with the police, Garsombke, like McLean, has been collecting information about the couple and their past, information that he hopes can be used in a criminal case.

According to Phil Parrott, a chief deputy district attorney for the Denver DA's office, that might be a possibility.

"We get 12,000 complaints every year, and we only file 350 cases a year," he says, explaining why his office didn't pursue the case after Casement filed his police report. "If we filed criminally on every one of those, that's all we'd be able to do."

McLean contacted his office back in 1995, Parrott says, but his records indicate that she never followed up with requested information. "I was particularly interested in the daycare fraud that was going on," he says. "The real-estate fraud would also be interesting. This was interesting to me then, and it's interesting to me now. It all raises the prospect of criminal investigation."

Nothing would make McLean happier. Or Garsombke. Or Stone or Casement or Aandahl, or Ranieri, Hernandez, Cusick, Aki or any of the other people who've had unhappy encounters with the Manchegos over the years.

"If I did this to someone else," Ranieri says, "I'd be in jail."

Ranieri hasn't seen the Manchegos since the day he evicted them. But he's seen their cars around the neighborhood, and every sighting brings back bad memories.

Aandahl runs into the Manchegos all the time at the Mayfair King Soopers and at the bank. "She chased me once," she says of Brenda. "Now we just ignore each other." Cohen has seen them around the area, too, and avoids them if he can.

Stone just bought another rental property; he's imagined them showing up there. "I keep my eyes out for them, that's for sure," he says, "and I've laughed about what I'd do if they turned up."

McLean glimpsed the Manchegos at the local post office where Juan keeps a P.O. box. She keeps up on their whereabouts by way of the mailman -- the same one who helped Franz.

All of them know that even if Garsombke is successful in evicting the Manchegos, they'll probably turn up somewhere nearby. They seem to love the neighborhood.