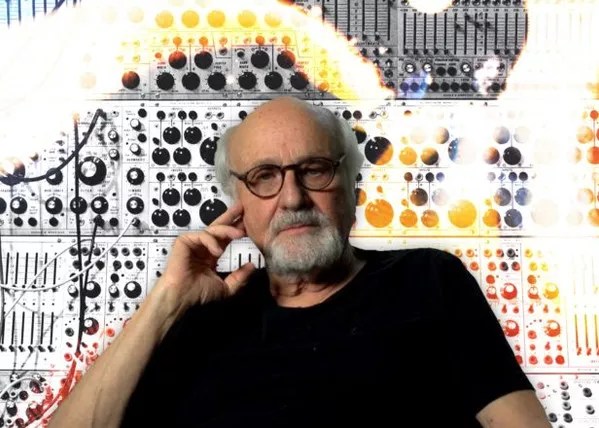

Morton Subotnick

Audio By Carbonatix

There was a period of time from the late ’40s until the early ’60s when Colorado was pivotal in a major transformation in global art and culture. But the key players had no idea they were making history. Neal Cassady, the infamous vagabond who went on to help define the psychedelic revolution and Beat culture, spent most of his life in Denver. He attracted Jack Kerouac to the city, and their experiences were immortalized in Kerouac’s On the Road, a book lauded by adventurers, psychonauts and artists alike. At the time, they had no idea they were about to sprout one of the most significant shifts in contemporary thinking of the twentieth century; they were just degenerates prowling the streets of LoDo.

It was also around this time that electronic-music pioneer Morton Subotnick, fresh out of high school, arrived in Denver to play in the Denver Symphony Orchestra and attend the University of Denver. Similar to Cassady and Kerouac, he was embarking on his own foray into the counterculture, and was equally clueless that he, too, was making history.

Subotnick’s work made an indelible impact on the future of music. He composed the first album of electronic music commissioned by a label, called Silver Apples of the Moon. He co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center, which held the first performance of Terry Riley’s “In C,” frequently considered the first minimalist music piece (in which Subotnick performed). He also started the California Institute of the Arts and helped design the Buchula 100, one of the first voltage-controlled synthesizers. These accomplishments would go on to influence a wide array of music and institutions, including the Lafayette Electronic Arts Festival, where a ninety-year-old Subotnick will play on Sunday, April 30.

Despite Subotnick never being aware of Kerouac or Cassady in Denver, his life intersected with other artistic giants who called the Queen City home. While playing in the Denver Symphony, Subotnick met violist Arthur Knebel, who invited him to a party in Central City hosted by painter Angelo Di Benedetto. At these parties, there were concerts, poetry readings and other displays of art.

At the first Di Benedetto party he attended, Subotnick befriended two other important figures in modern art: experimental film legend Stan Brakhage, widely considered the most important figure in avant-garde film, and composer Jim Tenney, who would eventually release some of the earliest algorithm-composed and computer-synthesized music. “We became the three – whatever they are there, the three something,” recalls Subotnick from his home in upstate New York. “We didn’t think history mattered, and we should just live [for] now.”

Subotnick attended the University of Denver in order to stay out of the Korean War. However, after two years at DU, it was perceived that he wasn’t taking his schooling seriously, and he was drafted and shipped back to his hometown of Los Angeles. “The Los Angeles musicians’ union had a deal with the Sixth Army Band at the Presidio in San Francisco, where if we enlisted for an extra two or three months, we could stay out of Korea and be in San Francisco. And so I did that, and that’s how I got to San Francisco, where everything started,” says Subotnick.

While playing around San Francisco as a clarinetist, he was awarded a fellowship to Mills College to study with Darius Milhaud, the renowned French composer famous for mentoring trailblazers such as Burt Bacharach, Dave Brubeck and Steve Reich. But there was a problem: “I accepted [the fellowship], but I couldn’t go because I hadn’t graduated with a bachelor’s degree yet,” recalls Subotnick, “By then I had a wife and a little child, and we drove back in a Volkswagen bug to Denver, where I could take two quarters or three quarters, the double overtime, reading novels and everything. I would play [performances of] The King and I at night in order to make money, and in the afternoons, I worked at Piggly Wiggly.”

After receiving his undergraduate degree at DU, Subotnick returned to the Bay Area to study under Milhaud, and the two became close. On Thursdays, they would meet, and Milhaud would reminisce about Paris in the ’20s while Subotnick talked to him about the modern avant-garde.

One day, during his final semester at Mills, Milhaud invited him to Aspen. Milhaud knew Morton was burning the candle at both ends in order to support his child and sick wife, and he wanted to give him a place where he could find time to compose (Milhaud gifted him $2,000 so he could afford to go).

It was in Aspen that Subotnick received the first negative response to his music – a response he would continue to receive through the rest of his career because of the challenging nature of his compositions.

During his first days in Aspen, he wrote a clarinet piece as well as one for a string quintet, and scheduled them to premiere at the Aspen Music Festival; neither was particularly challenging. But during this time, he also wrote a piece called “Sonata for Piano 4 Hands.”

“I knew that I had written something that had some freshness to it. [The piece] was in a traditional sonata form, but the last movement was a rondo. I had these loud notes that just appear from nowhere and gradually become the last five notes of the piece, and they just kept building through the piece until they dominated the last part; it was really dynamite,” remembers Subotnick. Despite Milhaud’s skepticism, they took the quintet and clarinet pieces off the festival bill, and added his sonata instead.

As the pianists he hired began playing the piece, Subotnick prepared himself for big applause – a sensation he had received his entire life, being a musical prodigy from a young age. What actually transpired was quite the opposite. “At the end of the second movement, the audience was hooting and hollering, making honking noises and barking like dogs,” recalls Subotnick.

In order to start the final movement, the two pianists just stared at the audience until they quieted down. It was during this final movement that things really got out of control: The audience stormed the stage, sending the two pianists fleeing to the wings. “I’ll never forget it: The audience was laughing, and this famous opera singer sitting in front of me turns to me and says, ‘Some kind of monkey wrote this,'” remembers Subotnick. “I was gonna die! I had never had an experience like that. I was the wunderkind all my life, and suddenly I was a demon!”

Fleeing the scene, Subotnick found himself at the back of the auditorium, where Milhaud was sitting in his wheelchair. Subotnick couldn’t see his face at first, but when Milhaud brought him down to his level, Morton noticed tears of laughter running down his face. “Thank you, my dear,” Milhaud exclaimed. “That reminds me of the old days.”

These intensely negative reactions to his music would follow Subotnick for the rest of his career as he continued to make increasingly more avant-garde music. “I once got a review in the New York Times that was two pages, and in big, bold font in the headline, it says that I’m ‘the devil of music,'” reflects Subotnick. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is kind of terrible to get it in the New York Times this way.’

“I ended up in therapy at one point in my life,” he continues, “and I remember one time the doctor said, ‘You know, one thing I don’t understand is, you are a very sensitive human being. You react strongly to your children and to people you love and so forth, but you go through these terrible experiences on stage. Why do put yourself in these situations?”

The reason is that Subotnick was never into music for the fame; he was into it to do something new. “I knew that I had a vision about the technology that turned out to be fairly accurate,” he says. “I was at the perfect age when the technological big bang was about to take over and change society, and so I gave myself to it in whatever way I could. That’s really the reason that they didn’t like my music, but that really wasn’t the point anymore.”

Morton Subotnick plays the Lafayette Electronic Arts Festival, 420 Courtney Way, Lafayette, Sunday, April 30. Tickets are $45.