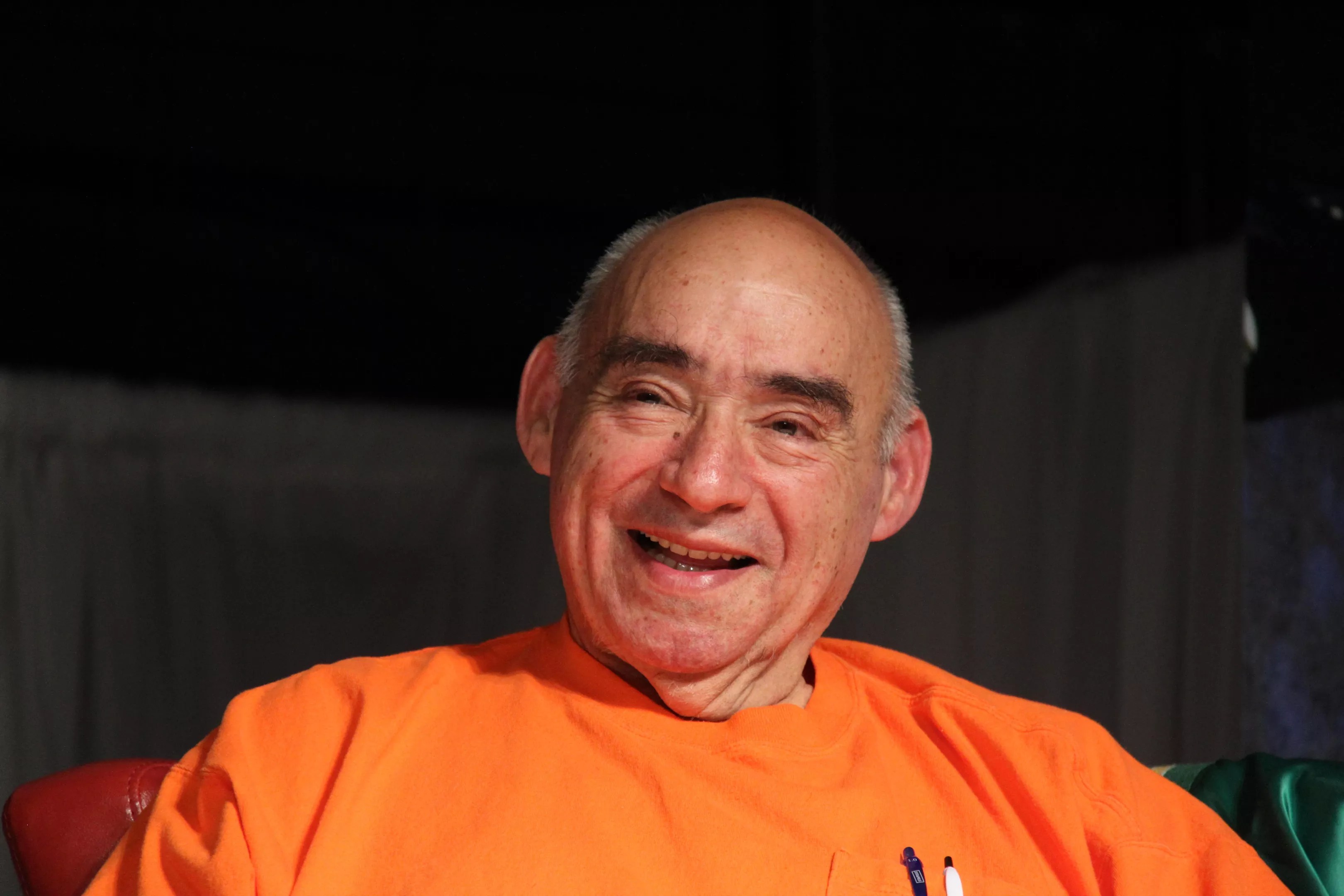

Kevin Preblud

Audio By Carbonatix

“Too much of a good thing can be wonderful.” That was one of the Martyisms frequently uttered by Marty Chernoff, whose 77th birthday would have been August 4, and whose life was celebrated at Tracks that day.

The room was packed with people wearing orange, Chernoff’s favorite color, and familiar faces, from drag queens to Governor Jared Polis. They were all members of Chernoff’s extended, and adopted, family, people who discovered a home at Tracks, whether they worked there or partied there or knew and supported those who did.

Chernoff didn’t set out to be the owner of a gay-club empire that at one point included four cities. A whiz kid from Brooklyn, he enrolled at the University of Denver, joined a Jewish fraternity, and paid for his education by winning poker games with his frat brothers.

From there, he went on to California to work as an actual rocket scientist. But he wasn’t done gambling. He got a real estate broker’s license and somehow wound up looking for a place in Denver for a client who wanted to make kitchen cabinets. While checking for real estate in what was then a dusty wasteland by the train tracks, he stopped in a bar called the Fox Hole, and asked the bartender if anything in the neighborhood was for sale.

Yeah, this place, the bartender replied, and after a little haggling – Chernoff offered $33,000, the bartender wanted $33,500 – Chernoff agreed to the deal, the bartender handed him the keys, and Chernoff owned a bar. At first he leased the place, but it often wound up back in his hands, and when an attorney running a secret gay bar fell behind on payments, Chernoff took it over and turned it into a gay bar himself. Even though he wasn’t gay. Even though he’d never run a bar.

The Fox Hole did well, though, and soon Chernoff was eyeing an old taxi warehouse across the street. He approached a friend, Neil Feinstein, to invest, and they turned it into Tracks. “From then on, the story just exploded,” remembered Neil, whose son, Andy Feinstein, later became Chernoff’s partner.

“Marty Chernoff was proud to be part of the LGBT community, and he was proud of that 24 hours a day, without regard to where or with whom he found himself,” said Randy Hardwick, the first manager of Tracks.

And Chernoff weathered the hard times in that community, as HIV hit and decimated his staff, his clientele. But he pushed on, closing the Tracks outposts in other cities, ultimately closing the original Tracks in 2000 and moving just blocks, but a world away, into what would become RiNo, where Tracks reopened at 3500 Walnut Street in 2003. Then came the Exdo Event Center next door, with more plans to come.

But the GLBTQ community was always at the heart for Chernoff.

Jared Polis addresses the crowd at Tracks.

Westword

Polis was born in 1975 and came of age far removed from the most horrific time of HIV. Still, “Tracks was a welcome refuge,” he remembered, recalling how he would dance at the original location. “Marty was a friend and an ally, truly a man ahead of his time.”

Mayor Michael Hancock followed Polis to the stage. “Chernoff gave disco balls a conscience,” he said.

Former Mayor Wellington Webb spoke, too. When his son, who was gay, wanted to open a bar, Chernoff offered advice and support. Webb lost that son a decade ago, but kept his fond feelings for Chernoff.

As did everyone in the room. The stories and the drinks flowed through the afternoon. Another Martyism: I don’t know what the problem is, but the answer is a free drink.”

There could never be too much of a good thing when that thing was Marty Chernoff. See for yourself in this video shown at the celebation of the life and legacy of Marty Chernoff.