Grant Stringer

Audio By Carbonatix

As Colorado policymakers begin an ambitious effort to drastically reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions over the next several decades, they now have a better understanding of where those cuts will have to come from.

A draft version of the state’s 2019 Greenhouse Gas Inventory, the most comprehensive report of its kind in five years, was released this week by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. It’s an update of a similar report released in 2014, as required by a 2009 executive order by then-governor Bill Ritter, and represents state officials’ best estimates of the total amount of heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide and methane that a wide range of sources across the state release into the atmosphere every year.

The world’s top climate scientists warned last year that in order to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change, governments around the world must cut these carbon emissions roughly in half by 2030 and achieve net zero emissions not long after that. Led by Governor Jared Polis and Democrats in the state legislature, Colorado has committed to meeting roughly similar targets – and while the CDPHE’s latest inventory offers some encouraging news about the progress that the state has already made, it also underscores the scale and scope of the challenge it faces over the next decade and beyond.

Here are four key takeaways from the report:

1. After decades of steady growth, Colorado’s emissions are finally falling, albeit slowly.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

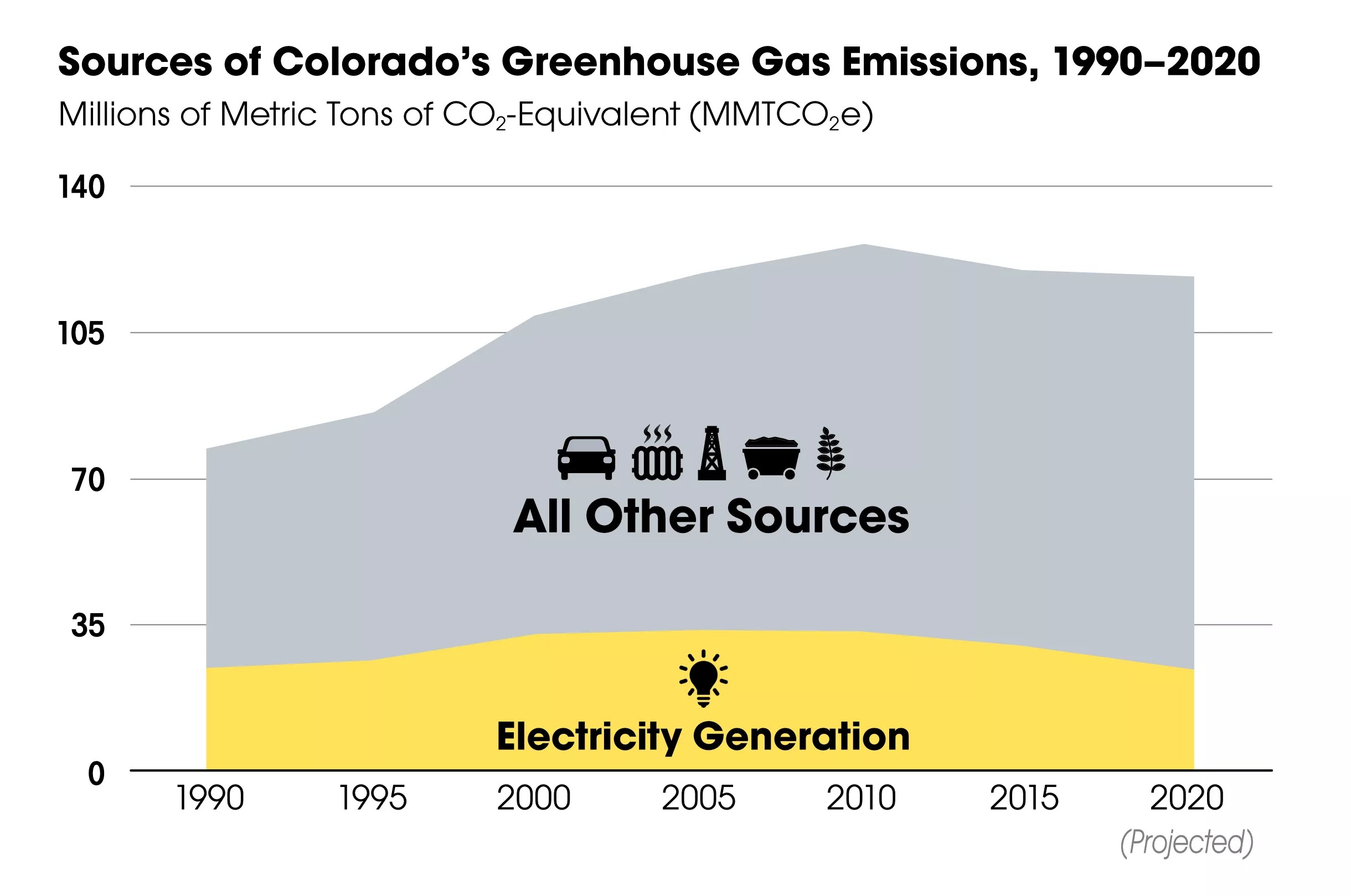

There’s at least one big piece of data in this week’s report that’s worth celebrating, if you’re a fan of habitable planets: Between 2010 and 2015, CDPHE estimates, Colorado’s overall greenhouse gas emissions fell slightly, from about 133 million tons of CO2-equivalent to 127 million tons.

That’s only a fraction of the reductions that scientists say are urgently needed, but it’s an important turning point. For over a century, Colorado’s overall emissions levels did nothing but rise steadily, driven by industrial development, economic expansion and population growth. Now, thanks to advances in technology and effective clean-energy policy, they’ve finally peaked, even as the state keeps growing; CDPHE projects statewide emissions to continue their modest downward trend next year, and through at least 2030.

The dip, however slight, puts Colorado ahead of the pack when it comes to decarbonization; after briefly flattening out a few years ago, total emissions both in the U.S. and worldwide are on the rise again. Activists have increasingly turned to state and local governments to enact strong climate policies in the face of federal inaction, and Colorado is poised to do its part – but small, gradual cuts won’t be enough.

2. Virtually all of the state’s climate progress has come from cleaner electricity generation, and emissions from other sectors keep rising.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

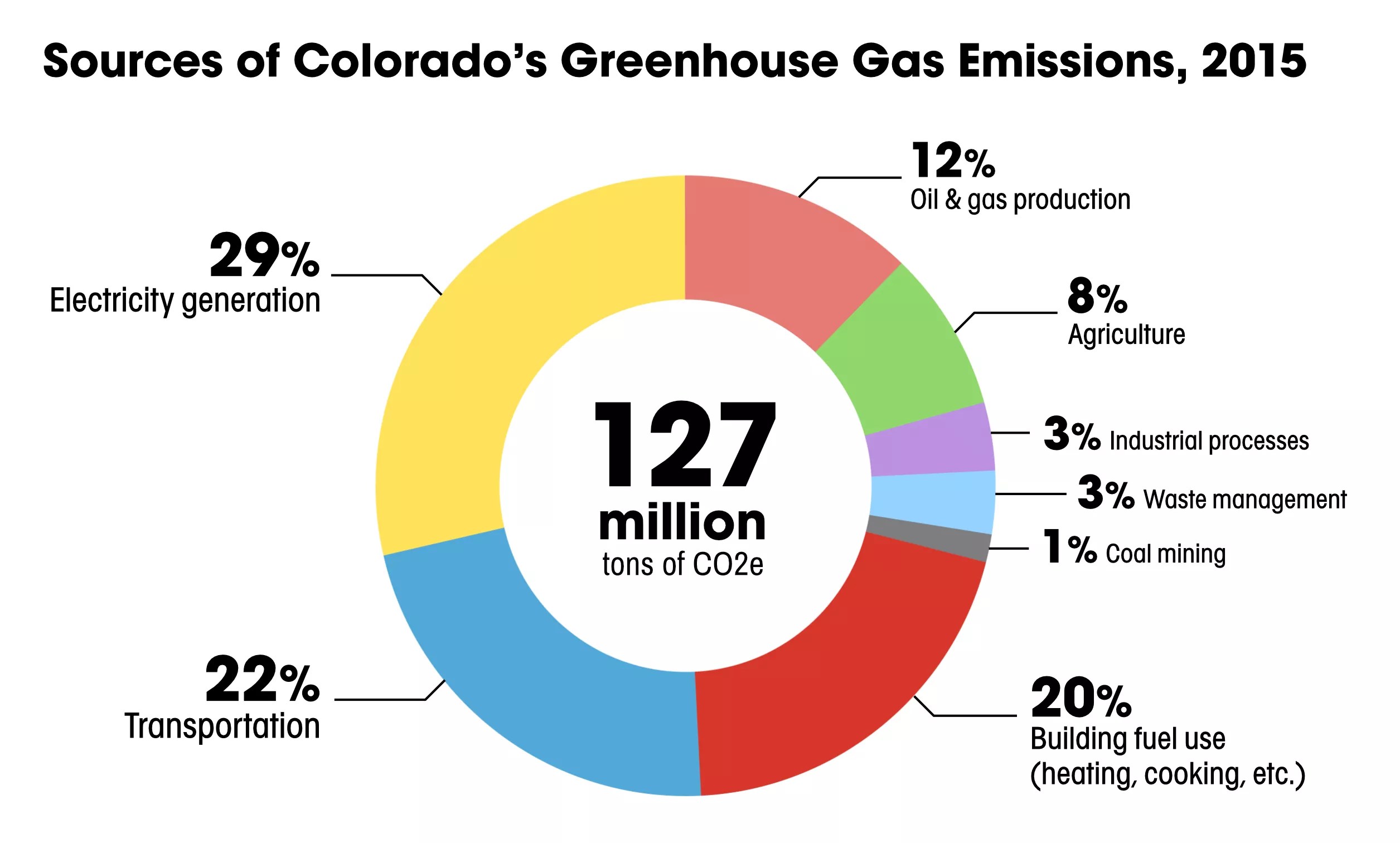

Power plants are Colorado’s largest source of carbon emissions, but they only make up 29 percent of the state’s yearly total – and while the phasing-out of coal-fired plants and an increase in wind and solar generation have reduced the electric sector’s carbon footprint, emissions from every other sector continue to rise, or at best stay flat. Emissions from Colorado’s electric sector are down slightly from 1990 levels – an impressive achievement, given the state’s population growth – but emissions from all other sources have almost doubled over that period.

Measures aimed at retiring coal plants and building more wind and solar capacity, while not easy or automatic, represent some of the lowest-hanging fruit in climate policymaking. Colorado can’t meet its climate goals without such policies, but with over two-thirds of the state’s emissions coming from other sectors, they won’t be nearly enough.

3. Decarbonizing Colorado’s economy will require changes to almost every sector and industry.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

As the electric sector continues to clean up its act, CDPHE’s inventory projects that by next year, transportation will overtake electricity as Colorado’s biggest source of carbon emissions. Electrifying the transportation sector – replacing gas-guzzling cars, trucks and other vehicles with electric alternatives – is a top priority for climate activists, and Colorado has taken steps to accelerate the transition. Natural gas-powered heating is another major emissions source, and making buildings more energy-efficient and transitioning to clean-heating technology will be another major focal point for the next decade of climate policy.

But there’s virtually no sector of Colorado’s economy that won’t have to make changes in the coming years if the state hopes to achieve the emissions cuts that scientists say are necessary. Methane, an especially powerful greenhouse gas, leaks out of oil and gas facilities and coal mines, and is produced by decomposing organic matter in landfills. Emissions from agriculture – mostly methane produced by cattle and other livestock, but also nitrous oxide released by soils and fertilizers – make up over 8 percent of the state’s total. The manufacturing of cement, steel and other common materials are significant emissions sources, too.

Some of the technology needed to cut emissions from these sources already exists; some of it doesn’t. The solutions might be costly, or require aggressive policy shifts or radical changes in consumer habits. Many of the toughest choices on the path to so-called deep decarbonization might still be a decade or more away, but eventually Colorado and other governments around the world will have to come up with some answers.

4. If the state is going to meet its climate goals, it needs to start making deeper cuts – fast.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

As of this year, Colorado has a set of emissions targets formally enshrined in state law. House Bill 1261, dubbed the Colorado Climate Action Plan and signed by Polis in May, commits the state to a 26 percent emissions cut by 2025, a 50 percent cut by 2030 and a 90 percent cut by 2050. If there’s anything that CDPHE’s new Greenhouse Gas Inventory makes clear, it’s that Colorado is nowhere near on track to meet those goals: The report’s projection for statewide emissions in 2030, about 122 million tons, is almost double the 63-million-ton target set by HB 1261.

Now, Polis, lawmakers and other state leaders have to figure out how to dramatically alter that trajectory over the next ten years. A preliminary “blueprint” for meeting HB 1261’s targets is expected to be completed by the Colorado Energy Office sometime next year, outlining specific pathways for reducing emissions in each sector – but it will be up to policymakers to implement its recommendations. Scientists warn that averting climate catastrophe will require “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes” – and the next few years will reveal whether Colorado is willing to make them.