Courtesy of Comilla Sasson

Audio By Carbonatix

Comilla Sasson is a Colorado emergency-room physician who thought she’d seen and done it all in the ER, including treating victims of the Aurora theater shooting as they arrived early in the morning of July 20, 2012. But she’d never seen anything like COVID-19 when the pandemic hit this country.

Marty Coniglio: You got involved in COVID-19 treatment by traveling to New York. What was that experience like?

Comilla Sasson: In my other life, I serve in the American Heart Association as the vice president for Science and Innovation for emergency cardiovascular care. We had just written the newest guidelines on how to take care of patients who have a cardiac arrest, for whom the heart stops. What do you do with this in the context of COVID?

That paper was published on the Thursday before I left, and then I was basically in New York on Sunday. I literally went there carrying my little paper that we had just finished writing [laughs]. I remember thinking to myself, “I have no idea what it does to people; I have no idea what it’s going to do to me, because it’s an infectious disease and I’m going to the hot spot of the country.” There’s fear, there’s apprehension, there’s a sense of novelty and interest because I have a Ph.D. in research, specifically in health disparities research. And we know that disproportionately, COVID affects these types of patients in a different way, right? Native Americans have three times the rate of death; we know that Blacks and Hispanics are dying at a much higher rate than Caucasians.

So I go to New York thinking, “What the hell am I doing? I have two kids at home, I have a safe, comfortable life in Colorado. Why am I going there?” But also just having this insane pull of wanting to go there because of curiosity about what the heck this thing is that we’re dealing with, and I had done a series of podcasts in my role with the Heart Association with people from Italy and China who had been at the front lines as it was unfolding there. There’s this intense sense of frustration just watching TV, sitting back and not being there. … It was really intellectually interesting, but more important, I just felt like if I was going to be a front-line person, I wanted to be there on the front lines helping.

“I just felt like if I was going to be a front-line person, I wanted to be there on the front lines helping.”

There was a sense of when I worked the Aurora shooting as one of the two ER attendings with this great team of people…everything kind of went down at about 12:30 a.m., and then at about two in the morning, all these people magically appeared out of nowhere. I don’t remember how they got there, but I remember seeing them all come and thinking, “Thank you so much for being here!” So I wanted to do that same sort of pay-it-forward in New York City. Because they were struggling; they were getting crushed. I wanted to be one of those people who could show up in the middle of the night when they were struggling and say, “Hey, look, let me help you. I don’t know what I can do, but put me to work.” That was the biggest draw for me.

That’s how your COVID-19 experience started. What have you been doing recently?

I’ve been working as an independent consultant to national Indian Health Service for the last four months, helping them get some of their hospitals up and ready for the surge in volume. I’ve been in Oklahoma, Montana and the Dakotas. … The last one I’ve been working with is the Standing Rock tribe, the Sioux tribe out in Standing Rock, which is basically North Dakota/South Dakota. Prior to that, we were in Eagle Butte; prior to that, we were in the Crow Agency, which is northern Montana, with the Northern Cheyenne and Crow; and then before that, we were in Claremore, Oklahoma.

I was a medical lead for the Critical Care Response Team. It would be myself as a medical lead, and then two critical care nurses and a respiratory therapist, and we were basically told to go to these hospital systems and say, “How do you take your current volume of patients, and what are you doing in the setting of the surge of COVID patients coming in?” Every single one of the facilities that we went to has now been through some variation of the surge. We had one facility that went from .2 patients per day and now it’s taking care of ten to twelve patients per day. These patients are sick, and they can’t transfer anybody out. In North Dakota, one hospital made sixteen phone calls to other facilities, and there was not one hospital that could take a patient from them.

The big thing that people don’t say when they tell you about beds is, I can make a bed out of anything, I can make a bed in a conference room, I can make a bed in a hallway, I can make it in an office. I’ve done all of those things – but if there isn’t a nurse to staff that bed, it doesn’t matter. The real issue is they might say they’re only 85 percent of capacity, but what they really need to know is what [that] translates to in terms of staffed beds. Because it may be 110 percent.

We are standardizing care of patients, from the screening part to the public-health interface, how they’re interfacing with the contact-tracing folks, all the way through to how they’re taken care of in the emergency department, who gets admitted, at what point do we admit them, what treatments do we give them, and then what kind of disposition plan – because we need to make sure that they have a safe place to go home to. So it’s from start to finish, and then also working on how to staff with, let’s say. an outpatient nurse who hasn’t worked a floor in thirty years. So we spent a lot of time doing contextualized training, taking that outpatient nurse and putting the nurse on the inpatient floor and saying, “Okay, here’s how you do it,” because for a lot of these folks, it’s dusting off cobwebs, it’s places they haven’t had to be in a very long time.

Probably the biggest challenge the health-care systems have right now is how to keep up with not only the volume of patients, but staff going out sick. Invariably, if you work twelve to eighteen hours a day in a COVID unit, you’re going to have people get sick; it just happens. And it may not even be in direct patient care; it may happen in the break room and it may happen outside, when they’re trying to take ten minutes without their mask on just to get some fresh air.

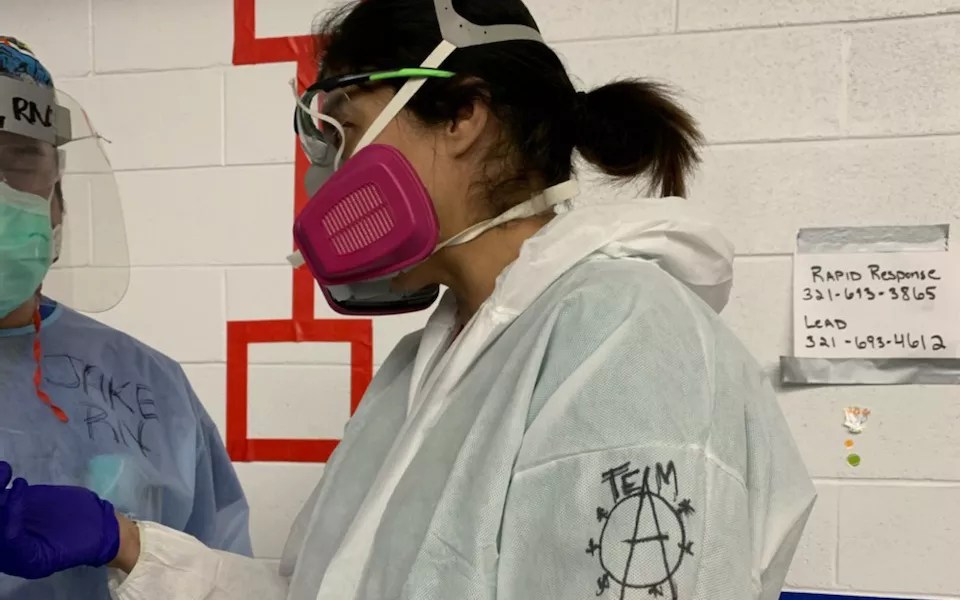

Comilla Sasson was on the front lines in New York this spring.

Courtesy of Comilla Sasson

You’ve been getting supplies and equipment for hospital systems. What is the process for doing that?

We’ve been really fortunate in that this program was actually started by Indian Heath Service, and they asked us to come in and help. So a lot of these hospitals have gotten funding; it was just a matter of getting through the logistics and also trying to understand what equipment you really need.

I think everyone’s first inclination is to go out and buy a bunch of ventilators, and that’s not what you need to take care of COVID patients. You need some sort of equipment to monitor them, and then you need these machines called high-flow nasal cannula machines that can deliver forty to sixty liters of oxygen per minute. In the beginning in March – it was like nine months ago; it feels like it was like twenty years ago – we would put everybody on a ventilator. Our treatment modality was if they’re sick, put them on a vent and see what happens.

Now it’s changed: We do every single thing possible to keep them off the ventilator, so it’s actually all of these other supportive-care things that we’re teaching the nurses how to do, we’re teaching the doctors how to do. We’re flipping the model in terms of how you take care of patients in the hospital.

In the “olden days” – what we call B.C., Before COVID – we would want to get people in and out of the hospital. If you have the flu or pneumonia, three to five days and you’d be at home. With COVID-19, we may have patients on high-flow nasal cannula for six weeks; you might be in the hospital for three months. People say, “Why are hospitals filling up?” It’s because it’s really difficult to discharge these patients, because there’s so much damage that happens to their lungs, so much damage that happens to all of their vital organs, they will be in the hospital for months. If they leave.

How do you and other health-care professionals feel about the attitudes some people have adopted with regard to what you need to do to protect others from COVID-19?

The big lesson I have learned in the last few months of being around COVID is, everything about COVID is simple. There’s not a lot of fancy drugs. There’s not a lot of fancy ways we treat you. A lot of what we do is because we get you in early. When you get COVID, some time between day five and day eleven, you’re going to get worse. And we’re going to tell you to:

1. Walk for one minute.

2. Immediately sing your ABCs.

If you get super-short of breath doing that, or can’t do it at all, then you need to come in to the ER and we’ll take care of you. We will put you on oxygen, we’ll give you some medications that are probably pretty cheap and effective. Then we watch and wait and let you get better over time.

“The thing that is really, really simple about COVID is that most of it is prevention.”

The thing that is really, really simple about COVID is that most of it is prevention. Most of it is wearing a mask. You wearing a mask, your other person wearing a mask. It’s not going to even a small family gathering over the holidays. It’s keeping your distance. If you’re in a poorly ventilated area, open your windows, go outside and get some fresh air. You know, nothing that we have talked about is expensive – but staying at home may be expensive or impossible. I want to put that out there, because I feel for the poor folks who have to, absolutely have to go to work. Those are essential workers.

Over the past few weeks, several people have come in with COVID-19 and told me that other family members had COVID, and that this all happened very recently. Everybody in their family has gotten sick. And I’m thinking to myself, “We don’t have space, we don’t have the ability to take care of you!”

That’s the pandemic frustration. People talk about pandemic fatigue, but pandemic frustration is something you see in a lot of health-care providers right now. If there was a coordinated national response, people would have the same guidance, schools would be closed consistently, businesses would close consistently when they needed to, you would have the ability to tell people to wear a mask, and it would be about public health, not politics. It would be about personal responsibility, and at the end of the day, all of those little tiny things that every single person does would add up to a health-care system that is absolutely ready to take care of you.

But because we’re all kind of unwilling to do our little itty-bitty piece right, take a little personal-responsibility piece, it turns into this massive surge of people. And the reason people die of COVID is not because we can’t take care of them – most of them we can – but people are dying because our health-care system is overwhelmed. And there’s all of these little things that people can do if they choose to, and if they have the proper kind of guidance on how to do it and when to do it. Do it in a coordinated way, and we could actually get our economy and our lives restarted quickly.

As everything has unraveled over the last nine months, it’s not even politics, it’s just common sense, really, just taking that personal responsibility. Can you hear the angst in my voice? This is all preventable. Vaccines are going to be helpful, but that’s also prevention. Getting a vaccine means that we are preventing you from getting COVID and helping to build herd immunity. That’s how you build herd immunity, not by going to a “COVID party” and hoping for the best.

If we can refocus the national discussion on personal responsibility and public health and lead with science, I think we’re going to have a very different, hopefully better next six to twelve months.

Comilla Sasson is an emergency room veteran.

Courtesy of Comilla Sasson

You see a lot of stuff online, one of which is, “How is a piece of cotton going to keep me or someone else from getting COVID?”

The truth is – and the CDC finally said it in the middle of November – masking is to protect others, but it is also to protect you from getting it.

We know from data from Australia this past winter – their winter, our summer – when everybody wore masks, their flu rates went down, their COVID rates are almost zero, and they were able to restart their economy. So masking works. If you’re wearing gaiters or the ones that have the big holes in them, you’re not going to get as much protection; it’s just not going to be as effective. But that being said, getting a mask, making your own mask – all of those things absolutely cut down spread.

COVID is like glitter. Every time somebody coughs, they cough glitter into the air, purple/pink glitter. It lands all over you and on everything that’s close to you, within six feet, even a little bit farther than that, depending on what you read (the CDC guidance says up to eight feet). Think about that: If you were to put a mask on and you coughed glitter, what would happen to that glitter? It would be caught in the mask.

“COVID is like glitter. Every time somebody coughs, they cough glitter into the air, purple/pink glitter.”

If we can just take what’s really common-sense stuff about COVID and put it into terms that people can understand and people buy into. If you have a family gathering and you have ten people who all have COVID and they’re all coughing in the same room with poor ventilation, that viral load, that glitter bomb in the air, just continues to accumulate. We know from the CDC guidance that came out on October 21 that it’s not just about how much time you’re spending with these people, it’s exposure over time, a cumulative amount of time. So if that cumulative exposure to the glitter bomb during Thanksgiving dinner because none of you are wearing masks while you’re eating and drinking and sitting next to each other and talking loudly and laughing and you’re coughing, all of that is going to get into the air; it’s going to get into your lungs and you’ll get sick, and you’ll likely get sicker because of the amount of viral load that you’re exposed to.

Where do you think the United States will be with respect to COVID infections and hospitalizations after the holidays?

All of us are just bracing for it. It’s like a nervous anticipation: “I thought I knew what to expect in April, and now I know what the disease is, but now I’m thinking, ‘Holy crap, how in the world am I going to take care of all of these patients who are going to show up at my doorstep?'” Because there is no place to put them.

I traveled on Friday, back from working five weeks away from my family, and both of my flights were packed to the core. The airports were bustling with people, with everybody saying how they’re going to visit their family, and it’s hard not to think to yourself, “Oh, my gosh, I’m just not ready, I’m exhausted, I’m so tired.” I am mentally spent, and physically and emotionally spent, and yet the idea is that not only is this a marathon where the finish line keeps getting farther and farther away, but you also know it’s turning into an ultra-marathon.

I’m going to run a 5K goes to I’m going to run a marathon to I’m gonna run an ultra to I don’t know if I’ll ever stop running, because I don’t think we have any kind of end in sight.

What is it in the American psyche that keeps us from managing this when we actually know what to do?

I would have a much higher position if I knew! In these communities that are having ridiculously high case positivity rates, like 40 and 50 percent, health-care pros are telling me they spent so much time prepping in March and April, and it felt like it was a dry run, and we were ready to go to war, and nothing ever happened. And I think we used up a lot of our goodwill. … We all got tired and we all got bored, and doing simple things like seeing your family is hard, especially if you haven’t seen your parents for nine months. I think people just got tired of it and they’re saying, “What am I waiting for?”

Dr. Fauci said it really well: “You’re fighting an invisible ghost.” You’re fighting a ghost, and until it’s tangible, right in front of you, people don’t realize what the heck we’re doing and why we’re doing it. It’s like telling my toddler to eat his vegetables because I know that ten years from now he’ll grow up to be strong and tall. That’s just a conceptual “thing” to him when he would just rather eat a brownie.

Over the course of the last nine months, we’ve seen people who do really well with COVID and have no symptoms, and people who die – but most of those people we don’t know. I have had people who are COVID deniers whom I’ve told, “You have COVID,” and they look at me and say, “You’re full of crap” and run out of my emergency department as I am running after them, trying to take their IV out. Depending on who you watch, depending on who you read, there are people who think this is a hoax. Even people in high levels of health care will tell you it’s not that bad.

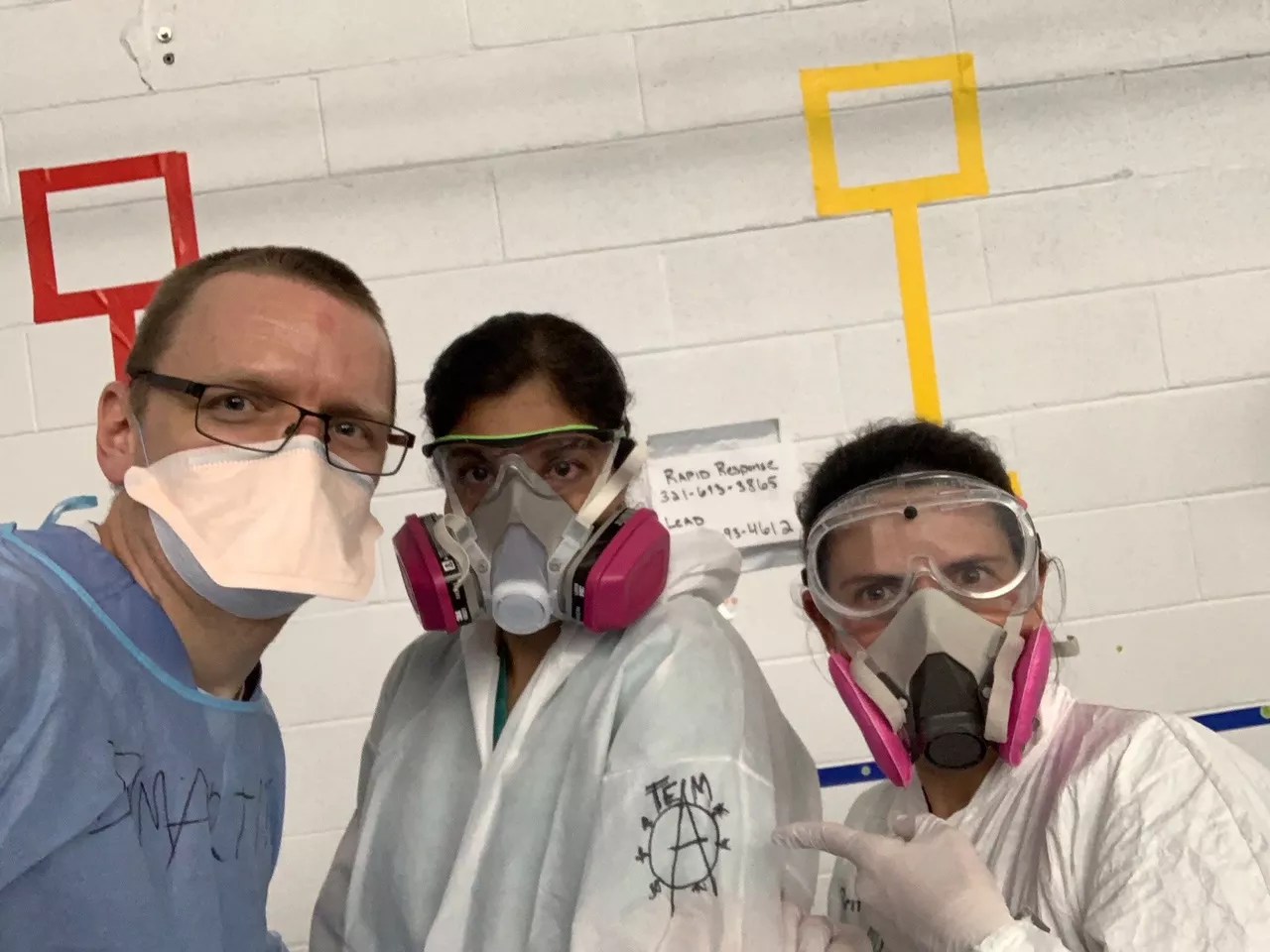

Dr. Comilla Sasson and colleagues on the job.

Courtesy of Comilla Sasson

We’re into flu season. How does COVID-19 compare to common strains of flu?

COVID-19 is a novel coronavirus, meaning that nobody has seen this before, nobody in the world has treated this. A year ago, this didn’t exist. We know it causes destruction in your lungs, it causes little clots all throughout your blood vessels that we may see or may not see, we know with some people it affects their heart directly and causes them to have heart problems, we know that in some people it affects their brain – that’s why they lose their sense of taste and sense of smell. It’s literally impacting their brains. There are so many different manifestations of COVID and so many different versions and ways in which people can be impacted by it. For the most part, people will likely do okay; they’ll be sick for anywhere from seven to fourteen days. We have a subset of patients who will need to be hospitalized. If you look at just the straight-up numbers of how many hospitalizations we have for the flu versus how many hospitalizations we have for COVID, it’s a magnitude of three, four, ten times more.

Even in a bad year, we’re never looking at 300,000 or more Americans who died from the flu. The severity of the illness is completely different. We give you medicine for flu, we give you antibiotics for pneumonia, we get you in the hospital…five or seven days later, you leave. With COVID-19 we’re looking at seven days, four weeks, six months in a hospital facility. It’s just so much longer, and that’s because of the level of damage that it can do to somebody’s body. So they are not even in the same category, in my mind, other than the fact that there’s probably some respiratory spread.

We’ve had the equivalent of the fatalities of 9/11 every day from COVID-19. Why do we not see the common purpose and togetherness around this pandemic?

You don’t have dramatic images to to remind you of these tragedies that are happening every day. It’s hard for me to even wrap my head around that, because I think, “How do you not believe this is real?” I literally held a phone up to somebody’s face so that their family could look at them for the last time before they went on the ventilator. That’s not normal. Folks are coming to the hospital and being admitted to the emergency department, and they haven’t seen their families in months, and I’m the only human interaction they have daily. That’s not normal. Our kids aren’t in school, we can’t go out to eat, we can’t see our families anymore…none of this is normal. So I honestly don’t get it.

Can you share a personal experience you’ve had with a patient?

I will tell you about one of my favorite patients, and I will try not to cry. Because it makes me cry. As an ER doc, usually I see them and then I get rid of them, I discharge them, I disposition them. Part of my role for the last four months is to be at patients’ bedsides multiple times a day. To be one of only a few people who sees them every day.

I had a patient I absolutely adored. I would bring her a caramel macchiato as her bribe for getting better. I would sneak in a coffee in the morning because she told me she was a coffee drinker, and I am empowered by coffee. We connected on that and on many other levels. And…she got worse. It was hard to see that, because I was watching her plan what she was going to do when she got out, and where she was going to go and which family she was going to see first. And she got worse, and she got worse, and she got worse after I left the hospital where I was working.

I got a phone call in the middle of the night, and I was trying to coach her through what was happening, and I’m telling her, “It’s going to be okay, it’s going to be okay,” and I have a sinking pit in my stomach. There’s nothing about this situation that is going to be okay. And she passed away. Patients become your family because they don’t have any visitors, they don’t have anybody else, and you’re the only person that is even there every day for them. So when they don’t walk out, it’s hard not to feel personally responsible for that. And to not feel like if this had happened a year ago, they would have been with their family, they would have said goodbye, they would have had all the conversations that they wanted to have. Instead, I’m having these conversations with them so I can tell their family.

It just…it’s such a lonely, lonely, lonely thing to have. COVID has this stigma attached to it. I’ve seen people get kicked out of their houses and not be allowed to go back even if they’re recovered and no longer infectious. I’ve seen people who literally can’t see their family. I’m the last hand they’re going to hold, I’m gonna be the last caramel macchiato she’ll ever have, right? Those are the stupid things that go through your head. It’s sad.

She wants you to mask up!

Courtesy of Comilla Sasson

If you could sit down with a group of folks who say,”My body, my choice, I am not going to wear a mask,” what would you say?

My first inclination is, “Screw you! What’s wrong with you? What goes through your head to make you think that you’re different or any more special than anyone else?” The fact that we have made this about personal freedom just blows my mind! It is not about personal freedom; it is about public health. It is about doing what’s right for you and for others.

Spend the day with me. Say goodbye to somebody for the last time and hold their hands when you know that they will never come off the ventilator. Spend a day with me and then tell me what you think. Tell me it’s not real. If you want to see loneliness and isolation, walk into a COVID unit where we’re wearing goggles and masks and gowns and hats and booties and gloves, and you look like you’re walking into an Ebola ward. Nobody touches you, nobody comes into your room unless they absolutely have to. And you spend hours upon hours upon hours by yourself – not because we don’t want to see you, but because we’re afraid that if we spend too much time with you, we will get sick.

Spend a day in the life of a COVID patient to know what it really feels like. “Air hunger” is that look that patients get when they are gasping for air and they’re just so horribly anxious, because they’re like, “I just can’t, I just can’t take that breath of fresh air.” To see people who are doing that looking at you, staring at you, and going like, “Help me, help me, help me,” and their eyes are wide open and they’re just working so freaking hard to breathe and to stay conscious. You’re trying to do everything you possibly can to prone them, which is when you put them on their side, laying on their belly, whatever we can do to try to get different parts of their lungs to work; you’re working as fast as you possibly can to get them just a few extra liters of oxygen because you think maybe that will keep them off the ventilator. You get to a point where you realize, I freaking have nothing left to do except put you on a ventilator, and as soon as I put you on a vent, your mortality goes up to 50 to 80 percent. Most people will not come off of the ventilator.

I want you to wear one of those N95 masks with another mask over it, with a face shield, plus the gown, and don’t eat or drink anything for twelve hours straight to not break your PPE.

I want you to spend a day in my life, then tell me you can’t wear a freaking mask to the grocery store.

Marty Coniglio’s mother, 96, passed away five days after testing positive for COVID-19 late in November.