Courtesy of Mike Strott

Audio By Carbonatix

At a time when mayoral appointees are jumping ship from the term-limited administration of Michael Hancock, the newly appointed executive director of Denver’s Department of Public Safety views the short time he may have in the job as an advantage.

“I’m thinking of this as the fourth quarter. I’m thinking of this as the last leg of a long race. This is the time to sprint. To give everything I have for eighteen months,” says Armando Saldate, a career law enforcement official tapped by Hancock on January 5 to fill the slot left open by the resignation of Murphy Robinson. Saldate’s appointment must still be confirmed by Denver City Council, a step that voters approved in 2020.

But Saldate is already looking past that step to what he can do on the job. “I know I can help,” he says. “I know I can make things better.”

He’s felt he could help this city before. Saldate, who’s originally from Arizona and served for over twenty years in the Phoenix Police Department – including a lengthy stint working with the FBI Phoenix Division tracking financial transactions of terrorist organizations – was reading a newspaper article in June 2014 about the Denver Sheriff Department. It detailed the 2010 in-custody death of Marvin Booker, which led to the sheriff stepping down and the department’s internal affairs section being reformed.

“I had a calling that I could help,” he recalls. “I was hearing that they wanted to bring in outside investigators. I applied, and I was lucky enough to get hired as an outside investigator.”

Saldate moved to Denver and took a job as a senior investigator with the Denver Sheriff Department. He then became a civilian commander in the Internal Affairs Bureau before ultimately transitioning to supervisor in the sheriff department’s Data Science Unit. From there, Saldate moved to Public Safety, which oversees the police, fire and sheriff departments. Under Robinson, who became director in January 2020, Saldate helped set up large-scale COVID-19 testing sites and also worked on establishing new initiatives related to homelessness, such as the city’s Early Intervention Team and Street Enforcement Team.

“You know, I’ve been right in the midst of working on this issue of unsheltered homelessness and the city’s response to that,” Saldate says. “It’s a difficult issue. We have a community that is very divided in its response.”

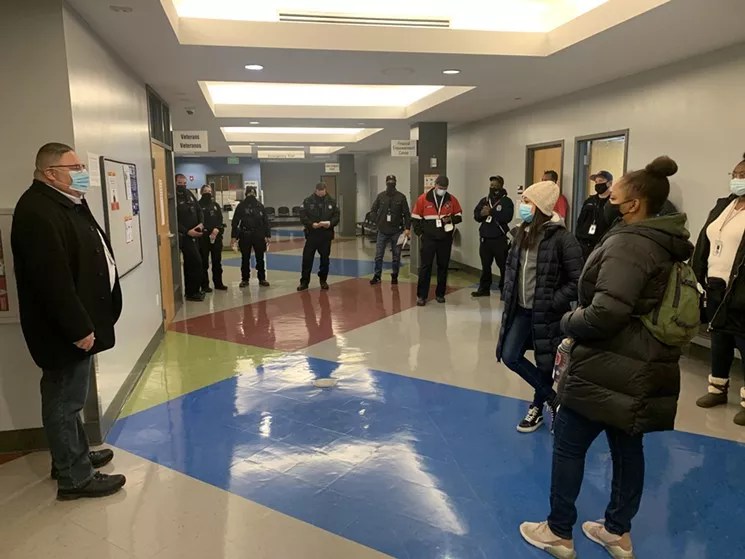

Armando Saldate talks with members of the Early Intervention Team.

Conor McCormick-Cavanagh

The Early Intervention Team, established in late 2020, includes city employees who visit budding encampments and offer services, with the goal of preventing them from growing into larger encampments. First set up in Public Safety, that team is now located in the Department of Housing Stability. The Street Enforcement Team is an even newer program that authorizes city employees to enforce laws typically associated with people experiencing homelessness, such as unauthorized camping and public urination. Although members of the team have started going out with officers on the Denver Police Department’s Homeless Outreach Team, they have not begun doing enforcement because they’re still waiting for their uniforms.

In the meantime, though, service providers have expressed concerns that this new team will further criminalize homelessness.

“First of all, I am very empathetic to our homeless community. I am very empathetic to people who are living on the side of the road, under a tarp, in extreme cold,” responds Saldate. “While I know people are dissatisfied with the city’s response or approach, the problem has grown so large, and I see people every day who are trying to strike that balance of trying to deliver services to people.”

Denver City Council rep Candi CdeBaca is no fan of Saldate’s work, and does not consider the EIT or SET programs a success.

“This is one of the worst choices the mayor could have made to replace former director Robinson,” she says. “Armando Saldate was behind some of Robinson’s most capricious and reckless decisions, as well as the city’s most recent muddled and failed homelessness responses. Mr. Saldate has broken trust with community and with our office at a time when we need trust and strong, collaborative relationships with the Safety Department the most.”

But Saldate believes in the work he’s done on homelessness, especially with the EIT. “I’ve seen miracles. Is it enough? No, because we have so much unsheltered homelessness,” he says.

Saldate commonly uses the phrase “harm reduction” when talking about how to approach the issues of homelessness and substance misuse. He supports the safe-camping site model for people experiencing homelessness because it’s an effective tool for reducing harm for those people, he says. However, he’s not ready to commit to pushing supervised injection sites for people who use intravenous drugs.

In New York City, two supervised injection sites went operational in the last weeks of the tenure of Mayor Bill de Blasio, marking the first time that such sites have been sanctioned by a government entity in the U.S. These types of sites exist in Canada and in Europe, and have been shown to virtually eliminate the risk of overdose death among those injecting drugs inside the facility, as staffers are able to reverse overdoses using naloxone.

Under the leadership of former Denver city councilman Albus Brooks, Denver approved a measure that created a framework for such sites; the city had been waiting on the Colorado General Assembly to pass its own legislation. But under the Trump administration, federal prosecutors had threatened municipalities with retribution if they allowed these sites to open.

“We need to study New York,” Saldate says. “I want to get more information. I want to get through the politics. I want to get through the strong feelings on either side of an issue. I want to see what the data says.”

And councilmembers – chief among them CdeBaca – will no doubt want to see what Saldate has to tell them about his plans for Public Safety as the Hancock administration heads into its final eighteen months.