Douglas County Sheriff’s Office via True Crime Daily

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: At the hearing previewed below, Erik Jensen’s sentence was changed from life without parole to parole-eligible after forty years. Get more details in our post “Erik Jensen Re-sentencing for Witnessing Juvie Murder Marked by Tears, Excuses.” Continue for our previous coverage.

At 9 a.m. today in Douglas County court, a hearing is scheduled to re-sentence Erik Jensen, who was condemned to life without parole for a murder he witnessed but didn’t commit in August 1999, when he was seventeen. But his father, Curt Jensen, isn’t letting his hopes get too high. He’s had more downs than ups in his two decades-plus fight to free his son, and he understands the toll crushed expectations can take.

“We’ve learned to do what the inmates do when they have parole hearings,” Curt reveals. “They walk in and say, ‘I don’t know which direction it’s going to go, and I don’t care.’ Because if they get really happy and believe something good is going to happen and it doesn’t, that’s when they kill themselves. We’ve known several people inside that’s happened to. So Erik and the family have learned the same hard lesson about going too far down the glass-is-half-full road.”

There are plenty of reasons why leniency should be seriously considered in Jensen’s case. For one thing, Nathan Ybanez, who was just sixteen when he used a fireplace tool to kill his mother, Julie Ybanez, admits that Jensen played no role in the crime. For another, Governor John Hickenlooper commuted Ybanez’s sentence in late 2018, shortly before leaving office, making him eligible for parole next year. This move was made in part because of extenuating circumstances; Ybanez’s parents had physically and sexually abused him prior to the brutal attack.

Another factor that should weigh in Jensen’s favor is Miller v. Alabama, a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the plaintiffs argued that “the Eighth Amendment forbids a sentencing scheme that mandates life in prison without possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders.” A majority of the justices agreed, calling for individualized sentencing by judges in capital cases involving juveniles.

The ruling would seem to have given Colorado courts leeway to reconsider the sentences of fifty inmates who’d been sentenced to life without parole for wrongs done as juveniles since the early 1990s, when state law was altered to give prosecutors a greater ability to try under-agers as adults. But legislators in Colorado took a different tack, creating a system in which offenders found guilty of first-degree murder as a juvenile would be eligible for parole after forty years, with so-called earned time (i.e., time off for good behavior) potentially lowering the jolt to thirty years.

If Douglas County Judge Theresa Slade follows this formula at today’s hearing, Jensen will be sentenced to parole-eligible after forty years – and attorney Jessica Peck, who’s serving as a spokesperson for the family (Jensen is represented by lawyer Lisa Polansky) expects that’s what will happen. Should this total be knocked down by a decade because of earned time, Jensen would still have to remain incarcerated for around nine more years, even though Ybanez, the person who actually took his mother’s life, will almost certainly be paroled in 2020.

“To me, that’s the most unbelievable of all the things that have happened in the last 21 years,” Curt says, “and certainly the hardest for us to accept. Here’s Nathan, who’s said Erik didn’t do it, that he wasn’t responsible, that he wasn’t in the deal. And yet Nathan is going to be free and Erik could still be in prison.”

Curt doesn’t want anyone to think he’s making excuses for his son’s actions. “My wife, Pat, and I started the Pendulum Foundation twenty years ago to get juvenile laws changed, and we’ve heard innumerable parents who give what I’ll call the parents’ alibi.” Instead, he readily notes that “Erik admits he assisted Nathan by helping him clean up after the fact, and he saw Nathan kill his mother and didn’t try to stop it.”

Jensen’s own comments about himself in a 2012 letter written to his family after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling are just as harsh. The entire document is accessible below, but one excerpt reads, “Prison makes you face hard truths about yourself and I’ve realized that prison is actually probably the best thing that could have happened to me. I was an angry, arrogant teenage boy who had every opportunity to succeed yet could never be satisfied, always looking for destructive ways to release the pent up angst and anger I had no reason to even feel. I make no excuses for the boy I was, I treated my family terribly, I lashed out at my little sister whose only offense was wanting to be around me more and who would inevitably forgive me enough to drag her husband and kids to a prison to visit me. I squandered opportunities, quit everything that was ever a challenge, and couldn’t wait to escape my ‘horrible’ life.”

Toward the end of the letter, Jensen asks, “So why did I come here? Maybe I came to prison to be the case that decides the fate of so many other kids who made a bad choice. Maybe I came to effect change in individuals I encounter. Or maybe I simply came to prison to become the man the outside could never teach me to be.”

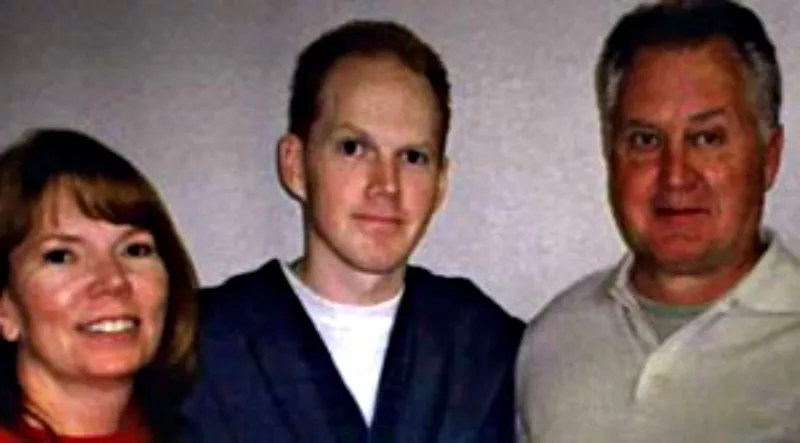

Erik Jensen with parents Pat and Curt.

Among those scheduled to testify at this morning’s hearing are a representative from the Limon Correctional Facility, where Jensen is currently housed; the spokesperson is expected to describe him as an exemplary prisoner who’s started multiple programs to assist fellow inmates. But while Curt shares this information with pride, he can’t disguise the frustration he feels over the sequence of events that began unfolding even before Julie Ybanez’s death.

In response to the abuse Nathan suffered, Curt divulges, “he ran away from home several times – and deputies in Douglas County captured him for his parents and took him home, over his screaming and crying objections. One day, he ran away in only his underwear on a very cold night and ran a very long distance to another home, but the deputies came and got him again – and the next day, Nathan’s father and a friend showed up in the driveway of that family with baseball bats, threatening to beat down the man who’d helped Nathan in the night. But the deputies showed up and simply said to the father, ‘Don’t do this. Be nicer.'”

As Curt sees it, “They could have arrested the father, or they could have taken Nathan out of the home and put him in another place. But they didn’t. So Pat and I talked to the family services people in Douglas County and asked them to please take Nathan out of the home. Their answer to us at the time was, ‘Sorry, but our policy is that any boy’ – not any boy or girl, just a boy – ‘who is thirteen years old or older can take care of himself.’ So Nathan had to stay there, and he finally cracked.”

The teens were promptly arrested after the murder, and Jensen was charged for being complicit in the crime. But at first the situation didn’t look as bleak as it became.

According to Curt, “The trial was supposed to take place in February of 1999, and Erik said, ‘I’m going to get into court and show everybody I didn’t do this.’ And the two lead people in the prosecution told us, ‘We think Erik should be given a lesser sentence and we think we can convince the district attorney’ – Jim Peters, who died a few years ago. They asked if Erik would let them do a continuance so he could get a lesser sentence, and Erik’s attorney convinced him that it was the right thing to do.”

The most recent booking photo of Erik Jensen.

Colorado Department of Corrections

This strategy backfired a few months later, in Curt’s view, because of the April 20, 1999, attack on Columbine High School, during which two teens killed twelve students and a teacher before taking their own lives. “That really changed everyone’s psyche relative to juveniles who committed crimes,” he believes. The deal for lighter punishment quickly evaporated, and the jury, which Curt says included the daughter of the Douglas County Sheriff at the time, brought the hammer down. Jensen was given life without parole on the murder beef and concurrent sentences of 24 years and six years on conspiracy and accessory counts.

Thus began a hellish stretch for Jensen, including two and a half years spent in solitary confinement for allegedly being involved in a fight. “If that had been me and I’d been kept in isolation for that long, I would have had to be treated at a mental hospital,” Curt contends. “But what happened to Erik was, he said to himself, ‘When I get out, I’m going to start moving my life forward so that it means something – because I don’t know if I’m ever going to be released.'”

That possibility exists now, and while George Brauchler, the current DA in the 18th Judicial District, declined to comment about Jensen’s case in advance of the hearing, he previously advocated on behalf of Curtis Brooks, who became a prison rehabilitation role model after being convicted of felony murder for a homicide in 1995, when he was fifteen. Hickenlooper commuted Brooks’s sentence last December, around the time he did likewise for Ybanez.

If the judge determines that Jensen must serve out the full forty years, options remain. Curt and Pat have been in communication with a member of Governor Jared Polis’s staff, and while no commitments have been made, the case is on the office’s radar. The Jensens could also file a lawsuit challenging Colorado’s juvenile lifer law, which Curt sees as running afoul of the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court judgment – but by the time the matter wound its way through the court system, his son might have already completed his sentence.

To Curt, the better solution would be for his son’s punishment to be considered in light of the Ybanez commutation. “If I thought about justice,” he says, “I would say justice would demand that if the one who did it gets to walk, the one who didn’t do it but was there should get to walk, too.”

Click to read Erik Jensen’s 2012 letter.